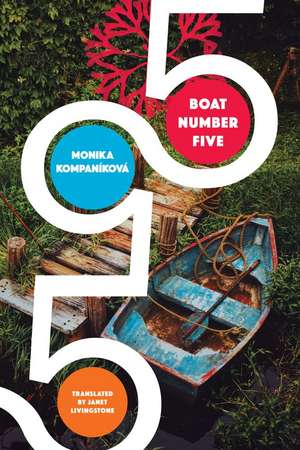

Boat Number Five: The Slovak List

Autor Monika Kompaníková Traducere de Janet Livingstoneen Limba Engleză Hardback – 17 noi 2021

Emotionally neglected by her immature, promiscuous mother and made to care for her cantankerous dying grandmother, twelve-year-old Jarka is left to fend for herself in the social vacuum of a post-communist concrete apartment-block jungle in Bratislava, Slovakia. She spends her days roaming the streets and daydreaming in the only place she feels safe: a small garden inherited from her grandfather. One day, on her way to the garden, she stops at a suburban railway station and impulsively abducts twin babies. Jarka teeters on the edge of disaster, and while struggling to care for the babies, she discovers herself. With a vivid and unapologetic eye, Monika Kompaníková captures the universal quest for genuine human relationships amid the emptiness and ache of post-communist Europe. Boat Number Five, which was adapted into an award-winning Slovak film, is the first of two books that launch Seagull’s much-anticipated Slovak List.

Preț: 155.00 lei

Nou

29.67€ • 32.24$ • 24.94£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 50.88 lei

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0857428896

Pagini: 212

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.99 kg

Editura: Seagull Books

Colecția Seagull Books

Seria The Slovak List

Notă biografică

Monika Kompaníková is considered one of the most outstanding writers of contemporary Slovak fiction. She is the author of four books for adults and five books for children and works as a publisher and book editor for Slovak newspaper Denník N. Janet Livingstone is a translator who lived in Bratislava for more than fifteen years.

Extras

I was in the garden, lying on the grass playing a simple game of stamina and patience. The dry August stalks of grass pricked me through my t-shirt, and I had to stay in that uncomfortable position until I had some sign that I could get up. The sign would be anything ordinary and unforeseen -a leaf falling on the ground, the edge of a shadow joining with a stone, a blackbird whistling. If it happened, I would move and scratch myself, if not, I’d keep lying there without moving. I was waiting for the sound of metal scraping on metal, for a train taking the curve below the garden plots. Until that trusty and familiar sound could be heard, I couldn’t move. The stalks were as sharp as needles, but I didn’t move an inch—I stuck it out, my arms flung out to the sides, hidden among the blades of grass, palms turned to the sky. I felt an ant crawling on my palm. I flinched a little, the ant crawled off my hand, and fora moment I lost myself in time and space. I felt like I was lying on the bottom of a boat that was drifting and lulling me to sleep. Sleep within sleep. Through my half-closed eyes I saw only the blue sky, clear and sparkling, the sides of the boat and one oar above me, set across the hull. When it’s time to wake up, I can take hold of the oar with both hands and pull myself up, I think. When will it be time to get up?

Then the slowly creeping shadow of the garden hut shaded my eyes and I felt that someone was standing over me. I was disoriented for a moment but felt safe. I turned my head, blinked and looked up. There wasn’t anyone standing there, just an apple tree and just beyond it the garden hut. The apple tree was swaying, and the movement of the tree fit perfectly into my dream. It looked thick and full of branches because every leaf was doubled by a shimmering shadow created in my eye. The unripe apples hung on the branches like small decorations, misfits with nowhere better to be. But it was enough to blink and rub my eyes with my fingertips and the apple tree’s true fecundity returned. Looking at the apples I realized that I had eaten almost nothing that day. I propped myself up on one elbow and closed my eyes again for a moment. I could have lain motionless for another half-hour, maybe even two hours, if I’d really wanted to. If I’d had a rea-son, if someone had made a bet with me, for example. For example, a bet for a roll or some hot cocoa. For that I would have done anything then. I was twelve years old.

I sat up and looked up and down and side to side to relax my stiff neck. Then I reached back and felt a circle of packed down soil in the grass that looked like a place where a barrel had been rolled away after many years.

The memory is shockingly vivid. I remember how I went over the soil several times with my palm. I pushed down any-thing that was sticking out and made it even with my fingers. I also remember how I turned over and looked for a long time at that empty place, as if I wanted to remove all doubt that it was really there or assure myself that I had not dreamt it. I could have dreamt about the boat and, at the same time, about that small grave. I could have dreamt that I was dreaming about the grave, because that kind of thing happens some-times. A person lies there thinking and falls asleep. They sleep for an hour or two.

Cuprins

Boat Number Five

Descriere

The moving yet humorous story of a girl struggling to care for herself and others in post-communist Slovakia.

Emotionally neglected by her immature, promiscuous mother and made to care for her cantankerous dying grandmother, twelve-year-old Jarka is left to fend for herself in the social vacuum of a post-communist concrete apartment-block jungle in Bratislava, Slovakia. She spends her days roaming the streets and daydreaming in the only place she feels safe: a small garden inherited from her grandfather. One day, on her way to the garden, she stops at a suburban railway station and impulsively abducts twin babies. Jarka teeters on the edge of disaster, and while struggling to care for the babies, she discovers herself. With a vivid and unapologetic eye, Monika Kompaníková captures the universal quest for genuine human relationships amid the emptiness and ache of post-communist Europe. Boat Number Five, which was adapted into an award-winning Slovak film, is the first of two books that launch Seagull’s much-anticipated Slovak List.