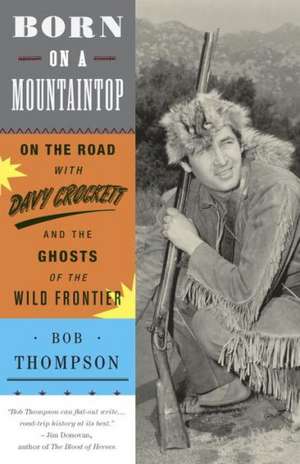

Born on a Mountaintop: On the Road with Davy Crockett and the Ghosts of the Wild Frontier

Autor Bob Thompsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 mar 2014

Pioneer. Congressman. Martyr of the Alamo. King of the Wild Frontier. As with all great legends, Davy Crockett's has been retold many times. Over the years, he has been repeatedly reinvented by historians and popular storytellers. In fact, one could argue that there are three distinct Crocketts: the real David as he was before he became famous; the celebrity politician whose backwoods image Crockett himself created, then lost control of; and the mythic Davy we know today.

In the road-trip tradition of Sarah Vowell and Tony Horwitz, Bob Thompson follows Crockett's footsteps from the Tennessee river valley where he was born, to Washington, where he served three terms in Congress, and on to Texas and the gates of the Alamo, seeking out those who know, love and are still willing to fight over Davy's life and legacy.

Born on a Mountaintop will be more than just a bold new biography of one of the great American heroes. Thompson's rich mix of scholarship, reportage, humor, and exploration of modern Crockett landscapes will bring Davy Crockett's impact on the American imagination vividly to life.

Preț: 104.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.95€ • 20.75$ • 16.47£

19.95€ • 20.75$ • 16.47£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307720900

ISBN-10: 030772090X

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 030772090X

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

BOB THOMPSON was a long-time feature writer for The Washington Post and the editor of its Sunday magazine. During his years at Post, he was known for his pieces on the intersection of American history and myth.

Extras

Chapter 1

“Play That Song Again”

Minutes after I walked into Alamo Plaza, I saw my first Davy Crockett ghost. He took the form of a solidly built man in an outsized coonskin cap--the kind with a cute little raccoon face as well as a bushy tail--who handed me a business card.

“He’s my great-great-great-grandfather,” David Preston Crockett said. “Yeah, I’m a grandson of the famous Davy Crockett.”

David had put on his Crockett finery for the occasion, which was the 175th anniversary of his ancestor’s death at the Alamo, most likely within a few yards of where we stood. In addition to the cap, he wore a long fringed jacket and matching pants that looked as if they were made of buckskin but weren’t.

“Would you believe this stuff came from Walmart?” he asked. Then he told me how he’d bought some chamois cloth, maybe ten years before, and learned to sew.

San Antonio, Texas, was my last stop on a search for traces of the historical and mythical Crockett--for the “ghosts,” as I’d come to think of them, of an extraordinary American life. Colorful threads of Davy’s story had been spun into legend while the man himself was still alive, and that story’s epic ending on the morning of March 6, 1836, had rendered him immortal. If you were hunting Crockett ghosts, on this anniversary weekend, the Alamo was the place to be.

For starters, there were all the other guys decked out in raccoon caps and brown fringed garments.

At one point, I saw two Davys in full regalia--both associated with a production company that specialized in historical films--shake each other’s hands in front of the Alamo church. Up walked a tourist who’d heard that the real Crockett might have carved his name on the church’s iconic facade. One of the Davys set her straight.

“Mr. Crockett was a gentleman. Mr. Crockett would not do that,” he said. “I’ll take that to the bank.”

A few hours later, waiting for a reenactment of the siege and battle to begin, I found myself standing next to two more Davys. Mike and Mark Chenault of Dallas were identical sixtyish twins wearing identical Crockett outfits. I asked one of them--I’m pretty sure it was Mark--what made them fans.

“Just Crockett’s devotion, his patriotism to America,” he told me. “He came all the way from Tennessee, you know, and the timing was just so perfect.”

I don’t think Davy would have agreed about the timing. The former congressman hadn’t planned on coming to Texas just to die. Still, dying was what the Crockett we’d all come to see was about to do.

Doug Davenport was a craggy-faced reenactor from the San Antonio Living History Association; he wore the usual cap and fringed coat, but his legwear set him apart. I had no idea whether the real Crockett ever wore white pants, but the unusual look, oddly enough, made Davenport seem more authentic, less like a Hollywood clone. This was a good thing, because the thirteen-day siege and battle about to be re-created were desperately serious. General Antonio López de Santa Anna had just marched into town to quash the Texas Revolution, taking Crockett and the rest of the vastly outnumbered garrison by surprise.

“Get everyone into the Alamo!” someone yelled.

“Give us a position, and me and the Tennessee boys will protect it for you,” Davy told his commanding officer, William Barret Travis, who assigned him to defend a wooden palisade that filled a gap in the south wall.

Then it was hurry up and wait.

It is not easy to evoke twelve tense days in which little actual fighting occurred, but in the short time allotted to them, Davenport and his colleagues did their best. Defiant cannon shots were fired. Messengers rode out and back. Longed-for help failed to arrive. “I would just as soon march out there and die in the open,” Crockett confessed at one point, just as the real Crockett is said to have done.

He didn’t get his wish. On the thirteenth day, shortly before dawn, Santa Anna finally ordered his men to storm the walls.

I lost track of Davenport during the booming, smoky chaos of the assault, then spotted him slumped against the palisade. There he stayed, cap twitching occasionally, until the words “Remember the Alamo!” came over the loudspeaker and the defenders sprang back to life. All available Davys were soon posing for photographs. Adults and children crowded around, and as I watched, I heard a young ponytailed mom try to convey to her son the seriousness of the moment he was experiencing.

“You are walking where Davy Crockett walked around,” she told him. “That is really cool!”

Decades before that mom was born, Walt Disney made Davy Crockett the coolest guy in American history--and walking where he walked can still give people chills.

Davy’s 1950s apotheosis came about through a wildly unpredictable combination of circumstances. Among them were the emergence of television as an irresistible cultural force; Disney’s drive to fund his innovative new Anaheim theme park; Fess Parker’s bit part in a film about giant mutant ants; and possibly the stickiest song ever written, with lyrics thrown together by a man who had never tried writing a song before. (All together now: “Davy, DAY-VEE Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier!”) Disney hadn’t planned to spark a Crockett craze any more than Crockett had planned to get killed at the Alamo--Walt just thought he was making a three-part TV series--which goes to show that even a marketing genius needs a helping hand from fate now and then.

Americans’ obsession with Davy Crockett also showed--and not for the first time--how powerfully his story resonated with that of the nation itself.

For anyone who loves U.S. history, Crockett is a wonderful point of entry, because he intersects with so much of it. You’ll find him in the middle of the bitter struggle between settlers and Indians, for example, taking different sides at different times. He personifies the radical expansion of democracy in the age of Andrew Jackson--far better, in fact, than the patrician, plantation-owning Old Hickory himself--as well as the unstoppable migration westward that drew ambitious, adventurous men and women to places such as San Antonio. Crockett was constantly pulling up stakes. He spent a lifetime striving to escape the “have-not” side of a class divide that Americans like to pretend doesn’t exist. A fierce resentment of the “haves” sparked his political career; getting too cozy with them helped end it.

There is far more to the Crockett story, however, than a fascinating man’s real life.

To start with, there’s Legendary Davy, a character who took shape long before the real David--the version of his name he preferred--left Tennessee for Texas. Created by the image-conscious politician himself, Crockett’s exaggerated backwoods persona was magnified and distorted, especially after he arrived in Washington, by the political and media culture of his time. The rapid spread of Crockett’s fame may come as a revelation to those who think of celebrity politics as a recent phenomenon. Here was a nineteenth-century John F. Kennedy whose PT-109 equivalent, fighting Indians, became grist for a campaign biography. Here was a Ronald ReaganߝSarah Palin blend whose common touch and theatrical persona inspired a play called The Lion of the West, with an unmistakably Crockettesque figure playing the title role.

David Crockett went to check out his alter ego at a Washington theater in December 1833. Congressman and actor exchanged bows.

Twenty-eight months later, the real man would be dead and Mythic Davy would take his place. Over the next 175 years, this Crockett would shift his shape from Texas martyr to tall-tale super-hero, from silent-movie star to icon of the TV generation--and, more recently, to symbolic flash point of the culture wars. Elusive and immortal, an Everyman who is also larger than life, Mythic Davy has always reflected Americans’ evolving sense of who we are.

Why did fate cast David Crockett in this role? Crockett himself is said to have offered the beginning of an explanation. “Fame is like a shaved pig with a greased tail,” he has been quoted as explaining, “and it is only after it has slipped through the hand of some thousands that some fellow, by mere chance, holds onto it!” As with many sayings attributed to Crockett, unfortunately, this one has been disputed, but it has a nice, self-deprecating ring and it suggests part of the answer.

Not all of it, though.

Something besides luck drew people to David when he was alive, and something besides commercial mythmaking--though there was plenty of that--drew them to his story after he was dead. Understanding his attraction and its staying power was one of my chief goals when I set out in pursuit of Crockett ghosts.

I had a more personal reason, too.

It’s not what you’re thinking. Unlike so many members of my generation, I had no fond childhood memories of Disney Davy, mostly because I never saw those Crockett shows. My father didn’t want a TV in the house, and as a New England kid, growing up just a few miles from Lexington and Concord, I was more attached to Paul Revere and Johnny Tremain anyway.

All of which meant that I was hopelessly unprepared when--forty years after his Disney debut--history’s most charismatic frontiersman took over my family’s life.

The car music was doing what car music is supposed to do. It was an old Burl Ives collection, folksy and melodic, and it was keeping the girls quiet while their mother drove. Burl sang “Shoo Fly,” Mona’s favorite, his opulent voice caressing each line (“I feel . . . I feel . . . I feel like a morning star . . .”). He sang “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” “What Kind of Animal Are You?,” and “Polly Wolly Doodle,” then broke into a bouncy number that Mona and her older sister, Lizzie, had never heard before.

“Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee,” Burl Ives sang. “Greenest state in the land of the free . . .”

When the music stopped, there was a moment of silence from the back seat. Lizzie broke it.

“Play that song again,” she said.

She’d hit her fourth birthday not long before, and her sister was two and a half. There’s no way she could have known what she was getting us into. Deborah and I didn’t know either. We were new parents, just beginning to understand that children rarely learn anything in exactly the way, or at precisely the time, adults expect them to. Kids see the universe as an endless web available for browsing. Click on Burl Ives. Click on Davy Crockett. Hmm, that’s interesting: let’s go to the next level, and the next, and now let’s follow that line over there. Before you can say “Remember the Alamo,” your firstborn is trying to make sense of the brutality of nineteenth-century Indian wars, the gender gap in frontier legends, and the complex relationship between heroic narratives and historical truth.

All before you’ve had time to research essential facts, such as: Where was Davy Crockett born, anyway?

Not on any mountaintop, it turns out.

After that first replay request, Lizzie began to ask for “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” again and again, and her mother started having flashbacks. Deborah, unlike me, could summon fond images of the little yellow record with the song in its grooves and of the hunky, buckskinned Parker playing Crockett on TV. So she fielded the girls’ initial questions as best she could, and we set out to supplement our knowledge.

One part of the task was to separate fact from fiction. Another was to explain the difference.

As it happens, there was quite a lot on Davy in the children’s section of our local library, most of it divisible into two categories. There were works of the Davy Crocket: Young Rifleman variety, which were either fact-based junior biographies or fictionalized versions of the historical Davy’s life. And there were tall tales, books with titles such as The Narrow Escapes of Davy Crockett, in which Davy appeared as a wholly legendary, Paul Bunyanߝlike figure who hitched rides on lighting bolts, climbed Niagara Falls on the backs of alligators, and walked across the Mississippi on stilts. One of the most helpful books--Robert Quackenbush’s Quit Pulling My Leg!--bridged the genres; the main text narrated the real history, while in the margins, a skeptical cartoon raccoon debunked assorted Crockett myths.

For weeks, Lizzie’s bedtime reading was all Crockett, all the time. When we hit the library, she’d head straight for the Crockett bios and start pulling them off the shelf. By now both she and Mona had memorized the Davy song. Was it true, they asked, that he “kilt him a b’ar when he was only three”? Probably not, we explained; that was a “tall tale.” Was it real that, as the Burl Ives version has it, he “fought and died at the Alamo”? Yes. Was he, in fact, born on that Tennessee mountaintop? Well, no, he was born on a river-bank near where Big Limestone Creek flows into the Nolichucky River, but yes, it was in what we now call Tennessee, except that Tennessee wasn’t quite a state yet, and . . .

There are a number of concepts in that Crockett ballad that require explanation when you’re talking to a preschooler. There’s statehood, for example, which gets you into the federal system, and there’s Congress, as in “He went off to Congress an’ served a spell,” which gets you into the whole notion of politics and representative government. Still, I’d never have predicted that we’d get so far into Davy’s historical context that we’d end up reading Lizzie, at her insistence, a 150-page American Heritage Junior Library biography of Andrew Jackson.

The real Crockett’s career was closely linked to Jackson’s. Davy did not fight “single-handed” in the Indian wars, as the song has it, but as a volunteer under General Jackson. After Jackson became president, Representative Crockett’s outspoken opposition to his fellow Tennessean became an irritant. Tennessee’s Jackson--dominated Democratic machine turned Crockett out of office and sent him on his fateful way to Texas.

But those are facts, and we weren’t confining ourselves to facts. To the girls, at that stage, “Andy” was essentially a mythic figure, just like “Davy.” What’s more--according to one of our favorite tall-tale books, Irwin Shapiro’s Yankee Thunder--they formed a two-person mutual admiration society.

“You’re the best man I ever clapped eyes on,” Shapiro’s Davy tells Andy, “and o’ course I’m Davy Crockett.”

“Then by the great horn spoon,” Andy roars in reply, “let’s find out which one o’ us is the best o’ the two! And that man will run for president!”

Bragging, roaring, battling: alert readers will have noticed that, while our children are both girls, Davy is as stereotypically guylike as they come. We noticed, too, and were glad to see that Crockett never got rejected as a “boy thing.” At the same time, we found it impossible to view him as anything other than what he was: the exceptionally likable hero of an exceptionally male narrative.

Neither of Davy’s real-life wives, we learned, gets much play in the biographies, although their stories, if they were better known, would shed light on both Crockett’s character and the American frontier experience. The legendary Davy comes with a legendary wife named Sally Ann Thunder Ann Whirlwind, a rough-and- ready charmer who grins the skins off bears and wins Davy’s heart by knotting six rattlesnakes together to form a rope. Lizzie and Mona liked Sally Ann Thunder Ann well enough, but there was never any question of divided loyalty. There is, after all, no Queen of the Wild Frontier.

We worried about this some, but not too much. That’s because we had a far more troubling part of the Crockett saga to deal with.

More than a year after Lizzie discovered Davy, we got her a plastic Alamo set, complete with bayonet-wielding blue plastic Mexicans and rifle-toting brown plastic Texans. She and her sister took to it immediately, arranging Crockett, Travis, Santa Anna, and the rest in a variety of warlike configurations. Yet Deborah and I couldn’t help but notice, at least until a neighbor boy joined the game, that their favorite activity was tucking in the troops for the night.

This was fine by us. Serendipity had blessed us with the Davy Crockett story, which had opened some wonderful historical windows. Precisely what happened at the end of the Alamo fight was one window we didn’t mind keeping shut for a while.

When Lizzie was first memorizing the Crockett ballad, she asked to hear the penultimate verse, the one with Burl Ives’s “fought and died at the Alamo” line, a few extra times. Beyond that, the girls didn’t actively pursue the idea of Davy’s death. They didn’t ignore it but seemed to be giving it time to sink in. The children’s books and audio tales we got them handled it gently. “We lost the battle, but we won the war” is how the CD from the Rabbit Ears Treasury of Tall Tales wraps things up, with narrator Nicolas Cage evoking Davy-the-Legend’s continued blissful existence in “the celestial vapors from where I speak.”

We did learn, well into our Crockett phase, that a historical death scene could produce obsessive interest. Looking for a “favorite president” to complement her sister’s beloved Andy, Mona settled on Abraham Lincoln. When we checked out picture books about Abe, she would stare at the inevitable assassination illustrations and ask us to read the relevant text over and over. A bit later, she asked her mother, “Is dying real? ”

None of this, however, prepared us for what happened when we got to the end of that American Heritage biography of Jackson. Lizzie was curled up in bed, with Deborah reading. Davy’s sparring partner had retired to his Tennessee home, where “as spring drifted into summer along the Cumberland,” he wrote a last letter to President James K. Polk, advising him on some incomprehensible financial matter. Deborah read on as the old man bade farewell to servants and friends and expired quietly on June 8, 1845, “long before the late-setting June sun had sunk behind the western hills.” Then she turned to Lizzie, and saw that tears were flooding down her face.

Lizzie loved Andy Jackson. His location in time was confusing. And it had never once occurred to her that he was dead.

I have to admit that I got choked up, too.

Not by Jackson’s death, though I was moved—as any parent would be—by my daughter’s grief. The more I had read about the real Andy, the less lovable he had seemed. And not by any Disney-implanted worship of his coonskin-capped adversary. By now, researching Davy’s story during our family recapitulation of the Crockett craze, I was fully aware that there was a flawed human being behind the irresistible Fess Parker reinvention.

And yet . . .

There’s a great scene in that Rabbit Ears narration in which Davy, to raise the spirits of the embattled Alamo defenders, climbs up on the ramparts one night, flaps his arms, crows like a rooster, and hurls “a good round of brag” into the menacing darkness. “I am half alligator, half horse and half snapping turtle with a touch of earthquake thrown in!” he roars as David Bromberg’s fiddle picks up the tempo in the background. “I can grin a hurricane out o’ countenance, recite the Bible from Genosee to Christmas, blow the wind of liberty through squash vine, tote a steamboat on my back, frighten the old folks, suck forty rattlesnake eggs at one sittin’ and swallow General Santy Anna whole without chokin’ if you butter his head and pin his ears back. . . . I shall never surrender or retreat.”

Listening to this for the first time, I was astonished to find that my eyes were moist.

Why had I found that fictionalized brag so moving?

I didn’t know.

The question would become one I set out to answer—years later, long after Lizzie and Mona had moved on from Davy, Andy, and Abe—as I marched deeper and deeper into Crockett territory.

The alchemization of history into myth has always fascinated me, and I wanted to explore the way the transformation got made in Davy’s case. Yet at the same time, no matter how many legends and myths I encountered, the real David’s story continued to move me.

Here was a man who started life as anonymous as you could get and almost as poor. He struggled, failed, pulled himself together, and struggled some more. He turned out to be better at politics than anything else, bear hunting excepted, and his feel for his frontier audience, along with a gift for humorous gab, earned him a high-profile job in Washington. There, like a lot of other politicians, he got in over his head. His “friends” built him up, then let him down when he stopped being useful. The road to Texas looked like the road to redemption, and when he got there, he thought he’d found the Promised Land.

“I am in hopes of making a fortune yet for myself and family bad as my prospect has been,” he wrote in his last letter home.

That letter was written in San Augustine, in east Texas, not far from where Crockett volunteered to fight for Texas independence. I wanted to go there. I wanted to check out the landscape farther north, near present-day Honey Grove, that Crockett called “the richest country in the world.” I wanted to visit Crockett’s birthplace on that east Tennessee riverbank, from which I was hoping you could at least see a mountaintop, and to look for traces of him in nearby Morristown, where he grew up in conflict with his father, a debt-ridden tavern keeper who liked to drink. I wanted to go to Alabama, where he and Jackson fought the Creeks; to the site of Mrs. Ball’s Boarding House, a few blocks from the White House, where Congressman Crockett bedded down; to Lowell, Massachusetts, one of the most revealing stops on his epic political book tour; and to more Crockett sites in middle and west Tennessee than I could keep track of, among them Lynchburg, Bean’s Creek, Lawrenceburg, Rutherford, and Memphis. I wanted to dig up rare Crockett almanacs, poke around the Disney location where Fess Parker thought he might get fired before his Davy could even get to the Alamo, and, of course, make a pilgrimage to the Shrine of Texas Liberty itself. Along the way, I figured, I would seek out historians, museum curators, park rangers, fellow pilgrims, and Crockett obsessives of all stripes—anyone who might help me get a feel for the real, legendary, and mythical character I was pursuing.

At some point, before my travel plans were complete, Deborah introduced me to a familiar-sounding children’s song by family favorites They Might Be Giants. It seemed, in its own weird way, to sum things up:

Davy, Davy Crockett

The buckskin astronaut

Davy, Davy Crockett

There’s more than we were taught

Yes, there is. The ghosts of David Crockett haunt the American psychic landscape. I couldn’t wait to start tracking them down.

From the Hardcover edition.

“Play That Song Again”

Minutes after I walked into Alamo Plaza, I saw my first Davy Crockett ghost. He took the form of a solidly built man in an outsized coonskin cap--the kind with a cute little raccoon face as well as a bushy tail--who handed me a business card.

“He’s my great-great-great-grandfather,” David Preston Crockett said. “Yeah, I’m a grandson of the famous Davy Crockett.”

David had put on his Crockett finery for the occasion, which was the 175th anniversary of his ancestor’s death at the Alamo, most likely within a few yards of where we stood. In addition to the cap, he wore a long fringed jacket and matching pants that looked as if they were made of buckskin but weren’t.

“Would you believe this stuff came from Walmart?” he asked. Then he told me how he’d bought some chamois cloth, maybe ten years before, and learned to sew.

San Antonio, Texas, was my last stop on a search for traces of the historical and mythical Crockett--for the “ghosts,” as I’d come to think of them, of an extraordinary American life. Colorful threads of Davy’s story had been spun into legend while the man himself was still alive, and that story’s epic ending on the morning of March 6, 1836, had rendered him immortal. If you were hunting Crockett ghosts, on this anniversary weekend, the Alamo was the place to be.

For starters, there were all the other guys decked out in raccoon caps and brown fringed garments.

At one point, I saw two Davys in full regalia--both associated with a production company that specialized in historical films--shake each other’s hands in front of the Alamo church. Up walked a tourist who’d heard that the real Crockett might have carved his name on the church’s iconic facade. One of the Davys set her straight.

“Mr. Crockett was a gentleman. Mr. Crockett would not do that,” he said. “I’ll take that to the bank.”

A few hours later, waiting for a reenactment of the siege and battle to begin, I found myself standing next to two more Davys. Mike and Mark Chenault of Dallas were identical sixtyish twins wearing identical Crockett outfits. I asked one of them--I’m pretty sure it was Mark--what made them fans.

“Just Crockett’s devotion, his patriotism to America,” he told me. “He came all the way from Tennessee, you know, and the timing was just so perfect.”

I don’t think Davy would have agreed about the timing. The former congressman hadn’t planned on coming to Texas just to die. Still, dying was what the Crockett we’d all come to see was about to do.

Doug Davenport was a craggy-faced reenactor from the San Antonio Living History Association; he wore the usual cap and fringed coat, but his legwear set him apart. I had no idea whether the real Crockett ever wore white pants, but the unusual look, oddly enough, made Davenport seem more authentic, less like a Hollywood clone. This was a good thing, because the thirteen-day siege and battle about to be re-created were desperately serious. General Antonio López de Santa Anna had just marched into town to quash the Texas Revolution, taking Crockett and the rest of the vastly outnumbered garrison by surprise.

“Get everyone into the Alamo!” someone yelled.

“Give us a position, and me and the Tennessee boys will protect it for you,” Davy told his commanding officer, William Barret Travis, who assigned him to defend a wooden palisade that filled a gap in the south wall.

Then it was hurry up and wait.

It is not easy to evoke twelve tense days in which little actual fighting occurred, but in the short time allotted to them, Davenport and his colleagues did their best. Defiant cannon shots were fired. Messengers rode out and back. Longed-for help failed to arrive. “I would just as soon march out there and die in the open,” Crockett confessed at one point, just as the real Crockett is said to have done.

He didn’t get his wish. On the thirteenth day, shortly before dawn, Santa Anna finally ordered his men to storm the walls.

I lost track of Davenport during the booming, smoky chaos of the assault, then spotted him slumped against the palisade. There he stayed, cap twitching occasionally, until the words “Remember the Alamo!” came over the loudspeaker and the defenders sprang back to life. All available Davys were soon posing for photographs. Adults and children crowded around, and as I watched, I heard a young ponytailed mom try to convey to her son the seriousness of the moment he was experiencing.

“You are walking where Davy Crockett walked around,” she told him. “That is really cool!”

Decades before that mom was born, Walt Disney made Davy Crockett the coolest guy in American history--and walking where he walked can still give people chills.

Davy’s 1950s apotheosis came about through a wildly unpredictable combination of circumstances. Among them were the emergence of television as an irresistible cultural force; Disney’s drive to fund his innovative new Anaheim theme park; Fess Parker’s bit part in a film about giant mutant ants; and possibly the stickiest song ever written, with lyrics thrown together by a man who had never tried writing a song before. (All together now: “Davy, DAY-VEE Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier!”) Disney hadn’t planned to spark a Crockett craze any more than Crockett had planned to get killed at the Alamo--Walt just thought he was making a three-part TV series--which goes to show that even a marketing genius needs a helping hand from fate now and then.

Americans’ obsession with Davy Crockett also showed--and not for the first time--how powerfully his story resonated with that of the nation itself.

For anyone who loves U.S. history, Crockett is a wonderful point of entry, because he intersects with so much of it. You’ll find him in the middle of the bitter struggle between settlers and Indians, for example, taking different sides at different times. He personifies the radical expansion of democracy in the age of Andrew Jackson--far better, in fact, than the patrician, plantation-owning Old Hickory himself--as well as the unstoppable migration westward that drew ambitious, adventurous men and women to places such as San Antonio. Crockett was constantly pulling up stakes. He spent a lifetime striving to escape the “have-not” side of a class divide that Americans like to pretend doesn’t exist. A fierce resentment of the “haves” sparked his political career; getting too cozy with them helped end it.

There is far more to the Crockett story, however, than a fascinating man’s real life.

To start with, there’s Legendary Davy, a character who took shape long before the real David--the version of his name he preferred--left Tennessee for Texas. Created by the image-conscious politician himself, Crockett’s exaggerated backwoods persona was magnified and distorted, especially after he arrived in Washington, by the political and media culture of his time. The rapid spread of Crockett’s fame may come as a revelation to those who think of celebrity politics as a recent phenomenon. Here was a nineteenth-century John F. Kennedy whose PT-109 equivalent, fighting Indians, became grist for a campaign biography. Here was a Ronald ReaganߝSarah Palin blend whose common touch and theatrical persona inspired a play called The Lion of the West, with an unmistakably Crockettesque figure playing the title role.

David Crockett went to check out his alter ego at a Washington theater in December 1833. Congressman and actor exchanged bows.

Twenty-eight months later, the real man would be dead and Mythic Davy would take his place. Over the next 175 years, this Crockett would shift his shape from Texas martyr to tall-tale super-hero, from silent-movie star to icon of the TV generation--and, more recently, to symbolic flash point of the culture wars. Elusive and immortal, an Everyman who is also larger than life, Mythic Davy has always reflected Americans’ evolving sense of who we are.

Why did fate cast David Crockett in this role? Crockett himself is said to have offered the beginning of an explanation. “Fame is like a shaved pig with a greased tail,” he has been quoted as explaining, “and it is only after it has slipped through the hand of some thousands that some fellow, by mere chance, holds onto it!” As with many sayings attributed to Crockett, unfortunately, this one has been disputed, but it has a nice, self-deprecating ring and it suggests part of the answer.

Not all of it, though.

Something besides luck drew people to David when he was alive, and something besides commercial mythmaking--though there was plenty of that--drew them to his story after he was dead. Understanding his attraction and its staying power was one of my chief goals when I set out in pursuit of Crockett ghosts.

I had a more personal reason, too.

It’s not what you’re thinking. Unlike so many members of my generation, I had no fond childhood memories of Disney Davy, mostly because I never saw those Crockett shows. My father didn’t want a TV in the house, and as a New England kid, growing up just a few miles from Lexington and Concord, I was more attached to Paul Revere and Johnny Tremain anyway.

All of which meant that I was hopelessly unprepared when--forty years after his Disney debut--history’s most charismatic frontiersman took over my family’s life.

The car music was doing what car music is supposed to do. It was an old Burl Ives collection, folksy and melodic, and it was keeping the girls quiet while their mother drove. Burl sang “Shoo Fly,” Mona’s favorite, his opulent voice caressing each line (“I feel . . . I feel . . . I feel like a morning star . . .”). He sang “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” “What Kind of Animal Are You?,” and “Polly Wolly Doodle,” then broke into a bouncy number that Mona and her older sister, Lizzie, had never heard before.

“Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee,” Burl Ives sang. “Greenest state in the land of the free . . .”

When the music stopped, there was a moment of silence from the back seat. Lizzie broke it.

“Play that song again,” she said.

She’d hit her fourth birthday not long before, and her sister was two and a half. There’s no way she could have known what she was getting us into. Deborah and I didn’t know either. We were new parents, just beginning to understand that children rarely learn anything in exactly the way, or at precisely the time, adults expect them to. Kids see the universe as an endless web available for browsing. Click on Burl Ives. Click on Davy Crockett. Hmm, that’s interesting: let’s go to the next level, and the next, and now let’s follow that line over there. Before you can say “Remember the Alamo,” your firstborn is trying to make sense of the brutality of nineteenth-century Indian wars, the gender gap in frontier legends, and the complex relationship between heroic narratives and historical truth.

All before you’ve had time to research essential facts, such as: Where was Davy Crockett born, anyway?

Not on any mountaintop, it turns out.

After that first replay request, Lizzie began to ask for “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” again and again, and her mother started having flashbacks. Deborah, unlike me, could summon fond images of the little yellow record with the song in its grooves and of the hunky, buckskinned Parker playing Crockett on TV. So she fielded the girls’ initial questions as best she could, and we set out to supplement our knowledge.

One part of the task was to separate fact from fiction. Another was to explain the difference.

As it happens, there was quite a lot on Davy in the children’s section of our local library, most of it divisible into two categories. There were works of the Davy Crocket: Young Rifleman variety, which were either fact-based junior biographies or fictionalized versions of the historical Davy’s life. And there were tall tales, books with titles such as The Narrow Escapes of Davy Crockett, in which Davy appeared as a wholly legendary, Paul Bunyanߝlike figure who hitched rides on lighting bolts, climbed Niagara Falls on the backs of alligators, and walked across the Mississippi on stilts. One of the most helpful books--Robert Quackenbush’s Quit Pulling My Leg!--bridged the genres; the main text narrated the real history, while in the margins, a skeptical cartoon raccoon debunked assorted Crockett myths.

For weeks, Lizzie’s bedtime reading was all Crockett, all the time. When we hit the library, she’d head straight for the Crockett bios and start pulling them off the shelf. By now both she and Mona had memorized the Davy song. Was it true, they asked, that he “kilt him a b’ar when he was only three”? Probably not, we explained; that was a “tall tale.” Was it real that, as the Burl Ives version has it, he “fought and died at the Alamo”? Yes. Was he, in fact, born on that Tennessee mountaintop? Well, no, he was born on a river-bank near where Big Limestone Creek flows into the Nolichucky River, but yes, it was in what we now call Tennessee, except that Tennessee wasn’t quite a state yet, and . . .

There are a number of concepts in that Crockett ballad that require explanation when you’re talking to a preschooler. There’s statehood, for example, which gets you into the federal system, and there’s Congress, as in “He went off to Congress an’ served a spell,” which gets you into the whole notion of politics and representative government. Still, I’d never have predicted that we’d get so far into Davy’s historical context that we’d end up reading Lizzie, at her insistence, a 150-page American Heritage Junior Library biography of Andrew Jackson.

The real Crockett’s career was closely linked to Jackson’s. Davy did not fight “single-handed” in the Indian wars, as the song has it, but as a volunteer under General Jackson. After Jackson became president, Representative Crockett’s outspoken opposition to his fellow Tennessean became an irritant. Tennessee’s Jackson--dominated Democratic machine turned Crockett out of office and sent him on his fateful way to Texas.

But those are facts, and we weren’t confining ourselves to facts. To the girls, at that stage, “Andy” was essentially a mythic figure, just like “Davy.” What’s more--according to one of our favorite tall-tale books, Irwin Shapiro’s Yankee Thunder--they formed a two-person mutual admiration society.

“You’re the best man I ever clapped eyes on,” Shapiro’s Davy tells Andy, “and o’ course I’m Davy Crockett.”

“Then by the great horn spoon,” Andy roars in reply, “let’s find out which one o’ us is the best o’ the two! And that man will run for president!”

Bragging, roaring, battling: alert readers will have noticed that, while our children are both girls, Davy is as stereotypically guylike as they come. We noticed, too, and were glad to see that Crockett never got rejected as a “boy thing.” At the same time, we found it impossible to view him as anything other than what he was: the exceptionally likable hero of an exceptionally male narrative.

Neither of Davy’s real-life wives, we learned, gets much play in the biographies, although their stories, if they were better known, would shed light on both Crockett’s character and the American frontier experience. The legendary Davy comes with a legendary wife named Sally Ann Thunder Ann Whirlwind, a rough-and- ready charmer who grins the skins off bears and wins Davy’s heart by knotting six rattlesnakes together to form a rope. Lizzie and Mona liked Sally Ann Thunder Ann well enough, but there was never any question of divided loyalty. There is, after all, no Queen of the Wild Frontier.

We worried about this some, but not too much. That’s because we had a far more troubling part of the Crockett saga to deal with.

More than a year after Lizzie discovered Davy, we got her a plastic Alamo set, complete with bayonet-wielding blue plastic Mexicans and rifle-toting brown plastic Texans. She and her sister took to it immediately, arranging Crockett, Travis, Santa Anna, and the rest in a variety of warlike configurations. Yet Deborah and I couldn’t help but notice, at least until a neighbor boy joined the game, that their favorite activity was tucking in the troops for the night.

This was fine by us. Serendipity had blessed us with the Davy Crockett story, which had opened some wonderful historical windows. Precisely what happened at the end of the Alamo fight was one window we didn’t mind keeping shut for a while.

When Lizzie was first memorizing the Crockett ballad, she asked to hear the penultimate verse, the one with Burl Ives’s “fought and died at the Alamo” line, a few extra times. Beyond that, the girls didn’t actively pursue the idea of Davy’s death. They didn’t ignore it but seemed to be giving it time to sink in. The children’s books and audio tales we got them handled it gently. “We lost the battle, but we won the war” is how the CD from the Rabbit Ears Treasury of Tall Tales wraps things up, with narrator Nicolas Cage evoking Davy-the-Legend’s continued blissful existence in “the celestial vapors from where I speak.”

We did learn, well into our Crockett phase, that a historical death scene could produce obsessive interest. Looking for a “favorite president” to complement her sister’s beloved Andy, Mona settled on Abraham Lincoln. When we checked out picture books about Abe, she would stare at the inevitable assassination illustrations and ask us to read the relevant text over and over. A bit later, she asked her mother, “Is dying real? ”

None of this, however, prepared us for what happened when we got to the end of that American Heritage biography of Jackson. Lizzie was curled up in bed, with Deborah reading. Davy’s sparring partner had retired to his Tennessee home, where “as spring drifted into summer along the Cumberland,” he wrote a last letter to President James K. Polk, advising him on some incomprehensible financial matter. Deborah read on as the old man bade farewell to servants and friends and expired quietly on June 8, 1845, “long before the late-setting June sun had sunk behind the western hills.” Then she turned to Lizzie, and saw that tears were flooding down her face.

Lizzie loved Andy Jackson. His location in time was confusing. And it had never once occurred to her that he was dead.

I have to admit that I got choked up, too.

Not by Jackson’s death, though I was moved—as any parent would be—by my daughter’s grief. The more I had read about the real Andy, the less lovable he had seemed. And not by any Disney-implanted worship of his coonskin-capped adversary. By now, researching Davy’s story during our family recapitulation of the Crockett craze, I was fully aware that there was a flawed human being behind the irresistible Fess Parker reinvention.

And yet . . .

There’s a great scene in that Rabbit Ears narration in which Davy, to raise the spirits of the embattled Alamo defenders, climbs up on the ramparts one night, flaps his arms, crows like a rooster, and hurls “a good round of brag” into the menacing darkness. “I am half alligator, half horse and half snapping turtle with a touch of earthquake thrown in!” he roars as David Bromberg’s fiddle picks up the tempo in the background. “I can grin a hurricane out o’ countenance, recite the Bible from Genosee to Christmas, blow the wind of liberty through squash vine, tote a steamboat on my back, frighten the old folks, suck forty rattlesnake eggs at one sittin’ and swallow General Santy Anna whole without chokin’ if you butter his head and pin his ears back. . . . I shall never surrender or retreat.”

Listening to this for the first time, I was astonished to find that my eyes were moist.

Why had I found that fictionalized brag so moving?

I didn’t know.

The question would become one I set out to answer—years later, long after Lizzie and Mona had moved on from Davy, Andy, and Abe—as I marched deeper and deeper into Crockett territory.

The alchemization of history into myth has always fascinated me, and I wanted to explore the way the transformation got made in Davy’s case. Yet at the same time, no matter how many legends and myths I encountered, the real David’s story continued to move me.

Here was a man who started life as anonymous as you could get and almost as poor. He struggled, failed, pulled himself together, and struggled some more. He turned out to be better at politics than anything else, bear hunting excepted, and his feel for his frontier audience, along with a gift for humorous gab, earned him a high-profile job in Washington. There, like a lot of other politicians, he got in over his head. His “friends” built him up, then let him down when he stopped being useful. The road to Texas looked like the road to redemption, and when he got there, he thought he’d found the Promised Land.

“I am in hopes of making a fortune yet for myself and family bad as my prospect has been,” he wrote in his last letter home.

That letter was written in San Augustine, in east Texas, not far from where Crockett volunteered to fight for Texas independence. I wanted to go there. I wanted to check out the landscape farther north, near present-day Honey Grove, that Crockett called “the richest country in the world.” I wanted to visit Crockett’s birthplace on that east Tennessee riverbank, from which I was hoping you could at least see a mountaintop, and to look for traces of him in nearby Morristown, where he grew up in conflict with his father, a debt-ridden tavern keeper who liked to drink. I wanted to go to Alabama, where he and Jackson fought the Creeks; to the site of Mrs. Ball’s Boarding House, a few blocks from the White House, where Congressman Crockett bedded down; to Lowell, Massachusetts, one of the most revealing stops on his epic political book tour; and to more Crockett sites in middle and west Tennessee than I could keep track of, among them Lynchburg, Bean’s Creek, Lawrenceburg, Rutherford, and Memphis. I wanted to dig up rare Crockett almanacs, poke around the Disney location where Fess Parker thought he might get fired before his Davy could even get to the Alamo, and, of course, make a pilgrimage to the Shrine of Texas Liberty itself. Along the way, I figured, I would seek out historians, museum curators, park rangers, fellow pilgrims, and Crockett obsessives of all stripes—anyone who might help me get a feel for the real, legendary, and mythical character I was pursuing.

At some point, before my travel plans were complete, Deborah introduced me to a familiar-sounding children’s song by family favorites They Might Be Giants. It seemed, in its own weird way, to sum things up:

Davy, Davy Crockett

The buckskin astronaut

Davy, Davy Crockett

There’s more than we were taught

Yes, there is. The ghosts of David Crockett haunt the American psychic landscape. I couldn’t wait to start tracking them down.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Born on a Mountaintop is an enjoyable journey along the trail of Crockett’s life and legend — part road trip and part history lesson....[Thompson's] storytelling displays considerable good humor and an admirable amount of research. You can almost see him smiling at some of the madcap stuff he is told along the way." --Washington Post

“Bob Thompson can flat-out write, and he paints a vivid picture here of David Crockett, who was a far more complex and interesting man—and myth—than his coonskinned, bear-hunting, Alamo-defending iconic image. He combines excellent research and a born storyteller’s skill to create a lively and entertaining look at one of America’s great characters. This is road-trip history at its best.” ߝ Jim Donovan, author of The Blood of Heroes

“Born on a Mountaintop explores the blurry boundary between America’s legends and histories, and how the relationship between the two often tells us much about the construction of belief in the absence of hard facts. And, it is also a great road trip--one that leaves you wanting to have ridden shotgun along the way.” ߝ Charles Frazier, author of Nightwoods and Cold Mountain

"Bob Thompson's shrewd and heartfelt account of his year-long journey through the thickets of Davy Crockett lore is essential reading for anyone who's ever worn a coonskin cap, dreamt of the wild frontier, or remembered the Alamo. A briskly entertaining book that nonetheless has serious things to say about how we memorialize--and inevitably mythologize--the iconic figures of our history." ߝ Gary Krist, author of City of Scoundrels

"I opened this book intending to skim a few pages but immediately became hooked. Thompson does a splendid job of evoking the life and legend of David Crockett--the immortal 'Davy' who captivated young Americans because of Fess Parker's portrayal in the 1950s, served as an icon for Anglo-Texans who venerated the memory of the Alamo, and served as a touchstone for anyone drawn to the image of backwoods characters who triumphed in America. By turns engrossing, hilarious, and moving, it undoubtedly will find a large and appreciative audience.” - Gary W. Gallagher, author of Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollyood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War

“Part travelogue, part biography, part history, Born on a Mountaintop is most of all a pure pleasure to read. The passion in Bob Thompson's search for the truth about Davy Crockett springs from every page, and by the end, his search has become our own.” -David Finkel, author of The Good Soldiers

“If Confederates In The Attic shifted its focus to frontier legend David Crockett, the result would be Born on a Mountaintop. Bob Thompson's highly personal and witty new book looks with perception at the real Crockett as opposed to the mythical "Davy," how Americans embraced the latter in his own time, and how popular culture has handled his multiple persona since his death. Crockett is a virtually irresistible character in his own right, but Thomson somehow succeeds in making him even more appealing.” - William C. Davis, author of Three Roads to the Alamo

"Bob Thompson blazes the dangerous trail between myth and history with the skill of a fine scholar and the wit of a born storyteller. I never realized the search for Davy Crockett, real and imagined, could be so enlightening and so much fun."

- Michael Kazin, Professor of History, Georgetown University and author of American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation

From the Hardcover edition.

“Bob Thompson can flat-out write, and he paints a vivid picture here of David Crockett, who was a far more complex and interesting man—and myth—than his coonskinned, bear-hunting, Alamo-defending iconic image. He combines excellent research and a born storyteller’s skill to create a lively and entertaining look at one of America’s great characters. This is road-trip history at its best.” ߝ Jim Donovan, author of The Blood of Heroes

“Born on a Mountaintop explores the blurry boundary between America’s legends and histories, and how the relationship between the two often tells us much about the construction of belief in the absence of hard facts. And, it is also a great road trip--one that leaves you wanting to have ridden shotgun along the way.” ߝ Charles Frazier, author of Nightwoods and Cold Mountain

"Bob Thompson's shrewd and heartfelt account of his year-long journey through the thickets of Davy Crockett lore is essential reading for anyone who's ever worn a coonskin cap, dreamt of the wild frontier, or remembered the Alamo. A briskly entertaining book that nonetheless has serious things to say about how we memorialize--and inevitably mythologize--the iconic figures of our history." ߝ Gary Krist, author of City of Scoundrels

"I opened this book intending to skim a few pages but immediately became hooked. Thompson does a splendid job of evoking the life and legend of David Crockett--the immortal 'Davy' who captivated young Americans because of Fess Parker's portrayal in the 1950s, served as an icon for Anglo-Texans who venerated the memory of the Alamo, and served as a touchstone for anyone drawn to the image of backwoods characters who triumphed in America. By turns engrossing, hilarious, and moving, it undoubtedly will find a large and appreciative audience.” - Gary W. Gallagher, author of Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollyood and Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War

“Part travelogue, part biography, part history, Born on a Mountaintop is most of all a pure pleasure to read. The passion in Bob Thompson's search for the truth about Davy Crockett springs from every page, and by the end, his search has become our own.” -David Finkel, author of The Good Soldiers

“If Confederates In The Attic shifted its focus to frontier legend David Crockett, the result would be Born on a Mountaintop. Bob Thompson's highly personal and witty new book looks with perception at the real Crockett as opposed to the mythical "Davy," how Americans embraced the latter in his own time, and how popular culture has handled his multiple persona since his death. Crockett is a virtually irresistible character in his own right, but Thomson somehow succeeds in making him even more appealing.” - William C. Davis, author of Three Roads to the Alamo

"Bob Thompson blazes the dangerous trail between myth and history with the skill of a fine scholar and the wit of a born storyteller. I never realized the search for Davy Crockett, real and imagined, could be so enlightening and so much fun."

- Michael Kazin, Professor of History, Georgetown University and author of American Dreamers: How the Left Changed a Nation

From the Hardcover edition.