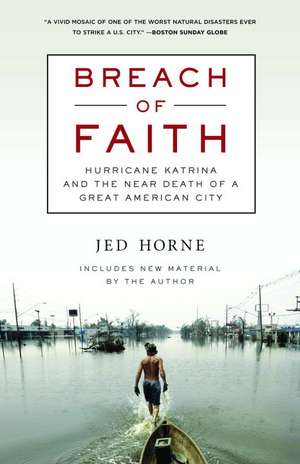

Breach of Faith: Hurricane Katrina and the Near Death of a Great American City

Autor Jed Horneen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2008

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

ALA Notable Books (2007), Helen Bernstein Book Award (2007)

As the Big One bore down, New Orleanians rich and poor, black and white, lurched from giddy revelry to mandatory evacuation. The thousands who couldn’t or wouldn’t leave initially congratulated themselves on once again riding out the storm. But then the unimaginable happened: Within a day 80 percent of the city was under water. The rising tides chased horrified men and women into snake-filled attics and onto the roofs of their houses. Heroes in swamp boats and helicopters braved wind and storm surge to bring survivors to dry ground. Mansions and shacks alike were swept away, and then a tidal wave of lawlessness inundated the Big Easy. Screams and gunshots echoed through the blacked-out Superdome. Police threw away their badges and joined in the looting. Corpses drifted in the streets for days, and buildings marinated for weeks in a witches’ brew of toxic chemicals that, when the floodwaters finally were pumped out, had turned vast reaches of the city into a ghost town.

Horne takes readers into the private worlds and inner thoughts of storm victims from all walks of life to weave a tapestry as intricate and vivid as the city itself. Politicians, thieves, nurses, urban visionaries, grieving mothers, entrepreneurs with an eye for quick profit at public expense–all of these lives collide in a chronicle that is harrowing, angry, and often slyly ironic.

Even before stranded survivors had been plucked from their roofs, government officials embarked on a vicious blame game that further snarled the relief operation and bedeviled scientists striving to understand the massive levee failures and build New Orleans a foolproof flood defense. As Horne makes clear, this shameless politicization set the tone for the ongoing reconstruction effort, which has been haunted by racial and class tensions from the start.

Katrina was a catastrophe deeply rooted in the politics and culture of the city that care forgot and of a nation that forgot to care. In Breach of Faith, Jed Horne has created a spellbinding epic of one of the worst disasters of our time.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 129.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 195

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.85€ • 26.99$ • 20.88£

24.85€ • 26.99$ • 20.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812976502

ISBN-10: 0812976509

Pagini: 440

Ilustrații: 3 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812976509

Pagini: 440

Ilustrații: 3 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Jed Horne, a metro editor of The Times-Picayune, was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his part in the paper’s coverage of Hurricane Katrina. His book Desire Street: A True Story of Death and Deliverance in New Orleans was nominated for the 2006 Edgar Award for nonfiction crime writing. He lives in the French Quarter with his wife.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

one

A Camille on Betsy’s Track

The big old camelback house on Lamanche Street was home to Patrina Peters, and had been for most of her forty-three years. Her parents lived in one of the paired front-to-back apartments that made up the ground floor—“shotgun” apartments in local parlance, because of their long, narrow layout. Zip, her brother’s widow, had stayed on in the other downstairs apartment after Kevin’s sudden death from a heart attack a year earlier. Peters and her two kids lived upstairs on the partial second floor that humped up on the backyard end of a camelback and gave this kind of house its name.

But if it was a cozy home for an extended New Orleans family, it was also a monument: to the self-reliance of Patrina Peters’s forebears and to their standing in the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, the rough-and-tumble working-class community some twenty blocks long and twenty-five blocks wide just downriver from the Industrial Canal. The waterway cut New Orleans more or less in half—a corridor of ship repair yards, steel fabricators, cold-storage warehousing, and the like that ran on a south-to-north axis from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain. West of the canal, on the apron of land along the bank of the Mississippi River, lay the older and generally whiter parts of the city: Bywater, Marigny, the French Quarter, the downtown area with its business corridor and gentrified warehouse district, the Garden District, and then, farther up St. Charles Avenue, the sprawling heterogeneous swath of housing and universities known as Uptown.

There was more to New Orleans than these original settlements along the river’s edge. As New Orleans was drained and landfilled early in the twentieth century, the city pushed out into the swamps, eventually reaching all the way to the lake, a shallow and brackish inland sea fifty miles long and twenty-five miles across. More recently, settlement had spread beyond the Lower Ninth into another, considerably larger welter of swampland and postwar subdivisions known as New Orleans East. People still spoke of wards in New Orleans, none so frequently as the Lower Ninth, mainly because it was geographically so succinct. But these political subdivisions—there were seventeen wards—for practical purposes had been supplanted in modern times by councilmanic districts, of which there were only five.

Peters knew what people said about the Lower Ninth, and she would hear a lot more of it on television in the weeks ahead. It would sicken and disgust her, the way the TV reporters figured everyone in the Lower Ninth was poor and on crack and couldn’t get out of the way of a hurricane if their lives depended on it, which maybe they did.

Peters’s great-grandfather on her mother’s side, the Reverend Allen Thomas, had been pastor of the Battleground Baptist Church when it was in Fazendeville, a storied African American hamlet on a corner of the Chalmette National Historical Park a few miles downriver in St. Bernard Parish. The bulldozing of Fazendeville in 1964 was the final hurrah in a campaign by preservationists to bring the field to a closer semblance of its condition during the Battle of New Orleans one hundred fifty years earlier. Anticipating the end, the pastor moved his flock and his eleven children and their many children onto land he had acquired in the Lower Ninth. His sons were builders and cabinetmakers—the reverend himself sidelined as a roofer—and in due course, a swath of several blocks was dominated by his family and his followers. Two generations later, Peters’s cousin the Reverend Eric Lewis, was assistant pastor at Battleground Baptist. Her uncle the Reverend Freddie McFadden III, a man who had found God after losing his spleen in a gunfight as a young man, presided several blocks away at St. Claude Baptist Church.

And if that didn’t put the lie to the Lower Ninth’s image as a redoubt of dysfunctional families mired in permanent poverty, Peters didn’t know what would. Her mother, June Johnson, had managed a school cafeteria in her day. Her father, Edward Johnson, had retired as manager of a downtown U-Park lot. Peters herself had earned a degree in clerical studies at Cameron, a commercial college on Canal Street, and had worked as a cosmetology instructor at a beauty school until 1995. Then for four years, until her health gave out, she held down a job at Xavier University with the big AME janitorial service, a black-owned business that also cleaned buildings and cut grass for the Orleans Parish public school system. A plump, cheerful woman who pulled her hair to the back of her head and held it there with an elastic band, Peters had a foggy voice much bigger than her diminutive frame. Her epilepsy was manageable with medication, but a heart condition and a worsening case of Crohn’s disease, a condition characterized by recurring intestinal inflammation, knocked her out of the workforce and onto disability in 1999. She was thirty-seven.

And so, while her downstairs kin watched TV that last Saturday night in August, and fretted over news reports of the huge storm winging across the Gulf, Peters headed upstairs, showered, and got into her nightgown. There had been a time when Trina, as everyone called her, had spent her Saturday evenings very differently, most every evening for that matter, a time when that Nina Simone voice of hers had been part of the smoky din of local bars and clubs—most especially when a storm was brewing in the Gulf. Storms were party time. In working-class neighborhoods still capable of civic occasion other than the late-night huddle along yellow slashes of crime scene tape, folks rolled grills right out to the curb when a storm was coming, and barbecued ribs and chicken for the whole block. After all, if the power failed, as it certainly would, uneaten food would just spoil. Merriment was already unfolding in the streets of the Lower Ninth and elsewhere across New Orleans as Peters took her medications and, by seven pm that Saturday night, was in her bed asleep.

She awoke the next morning to family dissension. Her mother had heard talk of a twenty-foot storm surge and Category 5 winds—winds above 155 miles per hour, the highest ranking on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. That would make Katrina even worse than Betsy, the apocalyptic 1965 tempest that had uprooted trees and stripped roofs of their shingling all across New Orleans, deeply flooding the Lower Ninth Ward. June had fled Betsy with Trina, then a child of three, and could see no reason to do otherwise this time. Trina’s great-uncle James McFadden, who lived just down the street, had been trapped on a rooftop by Betsy before extricating himself and joining in the Lower Ninth Ward rescue effort. “I’m not going to ride this one out,” her mother said. Peters’s way of dealing with the menace ahead was to stick to routine. All week, she had had it in mind to do a roast for Sunday dinner, with rice and gravy and peas and potatoes and salad, and she sure enough wasn’t inclined to give that up for a long drive upriver to an aunt’s place in St. John Parish.

But go, go if you need to, she told her mother, and take Damond. Damond was fourteen, a gangly basketball player already hitting the six-foot mark, but he was Peters’s baby, and when she thought about the roast, she had her son in mind as much as any of the other people who would have relished it. Keia, her daughter, would stay behind. They’d eat the roast together and play a little gin rummy in the late afternoon—a nice little mother-daughter moment in an apartment refurbished with the new furniture Peters had bought just two months earlier, a whole household’s worth. After all, moments like that were harder to come by and soon might be gone forever, now that Keia was twenty-four and about to graduate from college.

Damond fussed about the plan, and the roast was only part of it. He was the man of the house. He should stand by his mother and sister. But Peters would not hear of it. She and Keia would look after themselves. She would take no chances with Damond. As they loaded up the car, her uncle James came by to join with the others fleeing upriver. “Why you want to stay here, Trina?” McFadden asked. She recognized it as a man’s teasing way of begging her to leave, and she answered jauntily, trying to cool him out: “I’m way upstairs. You go ahead. You go ahead, but we are way upstairs.” When she saw his eyes starting to get watery, she tried a different tack. “I trust in God,” she said. “Whatever God wills, it will be done.” But her confidence was not contagious. Her uncle got into the car and looked back out at her through the open window. “I wish you were coming,” he said. His voice was thin, and then he looked away.

By seven pm that Sunday evening, Peters was again bathed, medicated, and in bed, the last night she would ever spend in her family home, indeed the last time she would ever even want to think of the Lower Ninth as home.

It wasn’t the morning news reports that did it. The mayor had made the evacuation mandatory, but he could do what he wanted. Peters wasn’t planning to leave; she had already passed up her ride. And it wasn’t the phone call from cousins over on Jourdan Road, four or five blocks away, to say that they were reconsidering their decision to stay put. In hindsight, Peters would remember being spooked as much as anything by a numerological coincidence: that exactly forty years separated 2005 from 1965, Katrina from Betsy. “You know, I think we made a bad decision,” she said to Keia as the symmetry of the two events dawned on her. “I have a funny feeling about this.”

And so that Monday morning—near dawn, but way too late—they started packing clothes, important papers, rounding up Peters’s medications, her dentures. “I gotta have my teeth!” she joked with her daughter, trying to break the worsening tension that had come over Keia. The cousins called back, panicky now. From the upper story of their house on Jourdan Road they could see right into the Industrial Canal, beyond the earthen levee and the concrete flood wall that ran along the top of it, and what they saw was nerve-racking: “The water is, like, kinda rising,” they told Patrina, “and it looks like it’s about to come over the levee.”

From the endless stories about Betsy, the memories of her uncle and so many others trapped in raging waters, Peters knew to share that sense of dread. The worst of it was realizing all this was just a prelude to the cyclone that lay ahead. The rising water would be storm surge funneling into the canal from the Intracoastal Waterway that connected to it from the open waters of the Gulf. Amplified by winds and rain, the surge would test mooring lines and knock barges against the massive concrete flood walls. But the eye of the hurricane was still miles way. At 6:10 am, maximum sustained wind speeds had dropped to 121 miles per hour—Category 3 strength—as Katrina made landfall some fifty miles southeast of New Orleans, on the withered finger of land that separated the Mississippi River from the open Gulf. But the eye’s distance hardly mattered, given the unusual width—four hundred miles—of the whirling disk that was Katrina.

From her upstairs rooms, Peters could see the trees toss mercilessly in the wind, and she could hear the bits of shingling begin to shred and fly against the walls of the house with a force that she knew would soon shatter glass. And then, suddenly the house shook with a concussive thud so violent that it knocked Keia back onto the bed and sent her mother scrambling to pull everything out of the closet so there would be room to shut themselves inside. In the months to come, many theories would be advanced as to exactly what sequence of events, what chain of natural forces and human failings, led to catastrophe in New Orleans, but to her dying day Peters, like many of her neighbors, would remain convinced that the thudding sound, a recurring motif in her dreams, was the sound of the Industrial Canal being deliberately dynamited. Why? To spare the fancier, whiter, upriver parts of New Orleans from the devastation that would have gone their way if the flood walls had ruptured on the other side of the canal. Hadn’t the city’s business elite done something like that during the catastrophic flooding of the Mississippi River valley back in 1927—blowing a hole in the levee and flooding rustic St. Bernard Parish, a realm of trappers and farmers, to ease pressure on the flood defenses at New Orleans? That was fact. History. “Everyone has a right to their opinion,” Peters would say when confronted with differing views about the explosive sound she heard as Katrina struck—that it was an electrical transformer blowing up or, more probably, the impact of a barge as it was swept over the walls of the ruptured Industrial Canal and thundered like a giant empty oil drum onto the street below the levee.

Whatever its cause, the sound prompted Peters to peek down the stairs into the kitchen—maybe the stove had blown up—and see, to her horror, that raging water had torn the wall right off the back of the house, stripping her of any illusion that her family home, even in the recesses of its snuggest closets, could provide any protection at all. Just then the cell phone rang again: Deidra, one of the cousins, jabbering in such terror it was hard to make out the words. They were on their roof, a half dozen of them, Deidra screamed over the howling wind. The water had lifted their house right off the pilings and was carrying it down the street.

Peters called 911 and begged for help. Instead she got a scolding: “You didn’t listen to your mayor? You should have listened to your mayor.” And with that, the operator hung up. Now she reached her mother on the cell: “Oh, Lord, Mama, we’re gonna drown. We love y’all, but we’re gonna drown.” With the whole upriver household huddled in a bedroom for the call, Damond had managed to wrench the phone from his grandmother and was speaking to Keia—his mother’s sobs audible in the background—when the phone went dead. In an instant, it seemed possible, he had lost both his mother and his sister, women he should have stayed home to protect. Damond began punching numbers into the cell phone, desperate to reach someone, anyone, back in New Orleans who could attempt a rescue mission to Lamanche Street. No calls went through. He tried again and again to reach his mother or Keia. Nothing.

On a hunch that a mattress might float, mother and daughter managed to haul one out through an upstairs window and onto the camelback’s lower front roof, water now lapping at its eaves. Neighboring houses had been wrenched free of their foundations and were easing out into the street. When a small cottage floating high in the water knocked up against their house, they heaved the mattress onto its more gently sloped roof and clambered aboard. The building swirled in the rising water and slid in behind the camelback, where it cropped up against a pecan tree, an old one that had been a fixture in the yard and in Peters’s memories ever since she was a little girl and her mama had sent her out there to play. “It was like God said ‘This is where I will anchor the house,’ ” she would later remember thinking.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Camille on Betsy’s Track

The big old camelback house on Lamanche Street was home to Patrina Peters, and had been for most of her forty-three years. Her parents lived in one of the paired front-to-back apartments that made up the ground floor—“shotgun” apartments in local parlance, because of their long, narrow layout. Zip, her brother’s widow, had stayed on in the other downstairs apartment after Kevin’s sudden death from a heart attack a year earlier. Peters and her two kids lived upstairs on the partial second floor that humped up on the backyard end of a camelback and gave this kind of house its name.

But if it was a cozy home for an extended New Orleans family, it was also a monument: to the self-reliance of Patrina Peters’s forebears and to their standing in the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, the rough-and-tumble working-class community some twenty blocks long and twenty-five blocks wide just downriver from the Industrial Canal. The waterway cut New Orleans more or less in half—a corridor of ship repair yards, steel fabricators, cold-storage warehousing, and the like that ran on a south-to-north axis from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain. West of the canal, on the apron of land along the bank of the Mississippi River, lay the older and generally whiter parts of the city: Bywater, Marigny, the French Quarter, the downtown area with its business corridor and gentrified warehouse district, the Garden District, and then, farther up St. Charles Avenue, the sprawling heterogeneous swath of housing and universities known as Uptown.

There was more to New Orleans than these original settlements along the river’s edge. As New Orleans was drained and landfilled early in the twentieth century, the city pushed out into the swamps, eventually reaching all the way to the lake, a shallow and brackish inland sea fifty miles long and twenty-five miles across. More recently, settlement had spread beyond the Lower Ninth into another, considerably larger welter of swampland and postwar subdivisions known as New Orleans East. People still spoke of wards in New Orleans, none so frequently as the Lower Ninth, mainly because it was geographically so succinct. But these political subdivisions—there were seventeen wards—for practical purposes had been supplanted in modern times by councilmanic districts, of which there were only five.

Peters knew what people said about the Lower Ninth, and she would hear a lot more of it on television in the weeks ahead. It would sicken and disgust her, the way the TV reporters figured everyone in the Lower Ninth was poor and on crack and couldn’t get out of the way of a hurricane if their lives depended on it, which maybe they did.

Peters’s great-grandfather on her mother’s side, the Reverend Allen Thomas, had been pastor of the Battleground Baptist Church when it was in Fazendeville, a storied African American hamlet on a corner of the Chalmette National Historical Park a few miles downriver in St. Bernard Parish. The bulldozing of Fazendeville in 1964 was the final hurrah in a campaign by preservationists to bring the field to a closer semblance of its condition during the Battle of New Orleans one hundred fifty years earlier. Anticipating the end, the pastor moved his flock and his eleven children and their many children onto land he had acquired in the Lower Ninth. His sons were builders and cabinetmakers—the reverend himself sidelined as a roofer—and in due course, a swath of several blocks was dominated by his family and his followers. Two generations later, Peters’s cousin the Reverend Eric Lewis, was assistant pastor at Battleground Baptist. Her uncle the Reverend Freddie McFadden III, a man who had found God after losing his spleen in a gunfight as a young man, presided several blocks away at St. Claude Baptist Church.

And if that didn’t put the lie to the Lower Ninth’s image as a redoubt of dysfunctional families mired in permanent poverty, Peters didn’t know what would. Her mother, June Johnson, had managed a school cafeteria in her day. Her father, Edward Johnson, had retired as manager of a downtown U-Park lot. Peters herself had earned a degree in clerical studies at Cameron, a commercial college on Canal Street, and had worked as a cosmetology instructor at a beauty school until 1995. Then for four years, until her health gave out, she held down a job at Xavier University with the big AME janitorial service, a black-owned business that also cleaned buildings and cut grass for the Orleans Parish public school system. A plump, cheerful woman who pulled her hair to the back of her head and held it there with an elastic band, Peters had a foggy voice much bigger than her diminutive frame. Her epilepsy was manageable with medication, but a heart condition and a worsening case of Crohn’s disease, a condition characterized by recurring intestinal inflammation, knocked her out of the workforce and onto disability in 1999. She was thirty-seven.

And so, while her downstairs kin watched TV that last Saturday night in August, and fretted over news reports of the huge storm winging across the Gulf, Peters headed upstairs, showered, and got into her nightgown. There had been a time when Trina, as everyone called her, had spent her Saturday evenings very differently, most every evening for that matter, a time when that Nina Simone voice of hers had been part of the smoky din of local bars and clubs—most especially when a storm was brewing in the Gulf. Storms were party time. In working-class neighborhoods still capable of civic occasion other than the late-night huddle along yellow slashes of crime scene tape, folks rolled grills right out to the curb when a storm was coming, and barbecued ribs and chicken for the whole block. After all, if the power failed, as it certainly would, uneaten food would just spoil. Merriment was already unfolding in the streets of the Lower Ninth and elsewhere across New Orleans as Peters took her medications and, by seven pm that Saturday night, was in her bed asleep.

She awoke the next morning to family dissension. Her mother had heard talk of a twenty-foot storm surge and Category 5 winds—winds above 155 miles per hour, the highest ranking on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. That would make Katrina even worse than Betsy, the apocalyptic 1965 tempest that had uprooted trees and stripped roofs of their shingling all across New Orleans, deeply flooding the Lower Ninth Ward. June had fled Betsy with Trina, then a child of three, and could see no reason to do otherwise this time. Trina’s great-uncle James McFadden, who lived just down the street, had been trapped on a rooftop by Betsy before extricating himself and joining in the Lower Ninth Ward rescue effort. “I’m not going to ride this one out,” her mother said. Peters’s way of dealing with the menace ahead was to stick to routine. All week, she had had it in mind to do a roast for Sunday dinner, with rice and gravy and peas and potatoes and salad, and she sure enough wasn’t inclined to give that up for a long drive upriver to an aunt’s place in St. John Parish.

But go, go if you need to, she told her mother, and take Damond. Damond was fourteen, a gangly basketball player already hitting the six-foot mark, but he was Peters’s baby, and when she thought about the roast, she had her son in mind as much as any of the other people who would have relished it. Keia, her daughter, would stay behind. They’d eat the roast together and play a little gin rummy in the late afternoon—a nice little mother-daughter moment in an apartment refurbished with the new furniture Peters had bought just two months earlier, a whole household’s worth. After all, moments like that were harder to come by and soon might be gone forever, now that Keia was twenty-four and about to graduate from college.

Damond fussed about the plan, and the roast was only part of it. He was the man of the house. He should stand by his mother and sister. But Peters would not hear of it. She and Keia would look after themselves. She would take no chances with Damond. As they loaded up the car, her uncle James came by to join with the others fleeing upriver. “Why you want to stay here, Trina?” McFadden asked. She recognized it as a man’s teasing way of begging her to leave, and she answered jauntily, trying to cool him out: “I’m way upstairs. You go ahead. You go ahead, but we are way upstairs.” When she saw his eyes starting to get watery, she tried a different tack. “I trust in God,” she said. “Whatever God wills, it will be done.” But her confidence was not contagious. Her uncle got into the car and looked back out at her through the open window. “I wish you were coming,” he said. His voice was thin, and then he looked away.

By seven pm that Sunday evening, Peters was again bathed, medicated, and in bed, the last night she would ever spend in her family home, indeed the last time she would ever even want to think of the Lower Ninth as home.

It wasn’t the morning news reports that did it. The mayor had made the evacuation mandatory, but he could do what he wanted. Peters wasn’t planning to leave; she had already passed up her ride. And it wasn’t the phone call from cousins over on Jourdan Road, four or five blocks away, to say that they were reconsidering their decision to stay put. In hindsight, Peters would remember being spooked as much as anything by a numerological coincidence: that exactly forty years separated 2005 from 1965, Katrina from Betsy. “You know, I think we made a bad decision,” she said to Keia as the symmetry of the two events dawned on her. “I have a funny feeling about this.”

And so that Monday morning—near dawn, but way too late—they started packing clothes, important papers, rounding up Peters’s medications, her dentures. “I gotta have my teeth!” she joked with her daughter, trying to break the worsening tension that had come over Keia. The cousins called back, panicky now. From the upper story of their house on Jourdan Road they could see right into the Industrial Canal, beyond the earthen levee and the concrete flood wall that ran along the top of it, and what they saw was nerve-racking: “The water is, like, kinda rising,” they told Patrina, “and it looks like it’s about to come over the levee.”

From the endless stories about Betsy, the memories of her uncle and so many others trapped in raging waters, Peters knew to share that sense of dread. The worst of it was realizing all this was just a prelude to the cyclone that lay ahead. The rising water would be storm surge funneling into the canal from the Intracoastal Waterway that connected to it from the open waters of the Gulf. Amplified by winds and rain, the surge would test mooring lines and knock barges against the massive concrete flood walls. But the eye of the hurricane was still miles way. At 6:10 am, maximum sustained wind speeds had dropped to 121 miles per hour—Category 3 strength—as Katrina made landfall some fifty miles southeast of New Orleans, on the withered finger of land that separated the Mississippi River from the open Gulf. But the eye’s distance hardly mattered, given the unusual width—four hundred miles—of the whirling disk that was Katrina.

From her upstairs rooms, Peters could see the trees toss mercilessly in the wind, and she could hear the bits of shingling begin to shred and fly against the walls of the house with a force that she knew would soon shatter glass. And then, suddenly the house shook with a concussive thud so violent that it knocked Keia back onto the bed and sent her mother scrambling to pull everything out of the closet so there would be room to shut themselves inside. In the months to come, many theories would be advanced as to exactly what sequence of events, what chain of natural forces and human failings, led to catastrophe in New Orleans, but to her dying day Peters, like many of her neighbors, would remain convinced that the thudding sound, a recurring motif in her dreams, was the sound of the Industrial Canal being deliberately dynamited. Why? To spare the fancier, whiter, upriver parts of New Orleans from the devastation that would have gone their way if the flood walls had ruptured on the other side of the canal. Hadn’t the city’s business elite done something like that during the catastrophic flooding of the Mississippi River valley back in 1927—blowing a hole in the levee and flooding rustic St. Bernard Parish, a realm of trappers and farmers, to ease pressure on the flood defenses at New Orleans? That was fact. History. “Everyone has a right to their opinion,” Peters would say when confronted with differing views about the explosive sound she heard as Katrina struck—that it was an electrical transformer blowing up or, more probably, the impact of a barge as it was swept over the walls of the ruptured Industrial Canal and thundered like a giant empty oil drum onto the street below the levee.

Whatever its cause, the sound prompted Peters to peek down the stairs into the kitchen—maybe the stove had blown up—and see, to her horror, that raging water had torn the wall right off the back of the house, stripping her of any illusion that her family home, even in the recesses of its snuggest closets, could provide any protection at all. Just then the cell phone rang again: Deidra, one of the cousins, jabbering in such terror it was hard to make out the words. They were on their roof, a half dozen of them, Deidra screamed over the howling wind. The water had lifted their house right off the pilings and was carrying it down the street.

Peters called 911 and begged for help. Instead she got a scolding: “You didn’t listen to your mayor? You should have listened to your mayor.” And with that, the operator hung up. Now she reached her mother on the cell: “Oh, Lord, Mama, we’re gonna drown. We love y’all, but we’re gonna drown.” With the whole upriver household huddled in a bedroom for the call, Damond had managed to wrench the phone from his grandmother and was speaking to Keia—his mother’s sobs audible in the background—when the phone went dead. In an instant, it seemed possible, he had lost both his mother and his sister, women he should have stayed home to protect. Damond began punching numbers into the cell phone, desperate to reach someone, anyone, back in New Orleans who could attempt a rescue mission to Lamanche Street. No calls went through. He tried again and again to reach his mother or Keia. Nothing.

On a hunch that a mattress might float, mother and daughter managed to haul one out through an upstairs window and onto the camelback’s lower front roof, water now lapping at its eaves. Neighboring houses had been wrenched free of their foundations and were easing out into the street. When a small cottage floating high in the water knocked up against their house, they heaved the mattress onto its more gently sloped roof and clambered aboard. The building swirled in the rising water and slid in behind the camelback, where it cropped up against a pecan tree, an old one that had been a fixture in the yard and in Peters’s memories ever since she was a little girl and her mama had sent her out there to play. “It was like God said ‘This is where I will anchor the house,’ ” she would later remember thinking.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Horne, editor of the "New Orleans Times-Picayune," takes readers into the private worlds and inner thoughts of Hurricane Katrina victims from all walks of life to weave a tapestry as intricate and vivid as the city itself.

Premii

- ALA Notable Books Winner, 2007

- Helen Bernstein Book Award Nominee, 2007