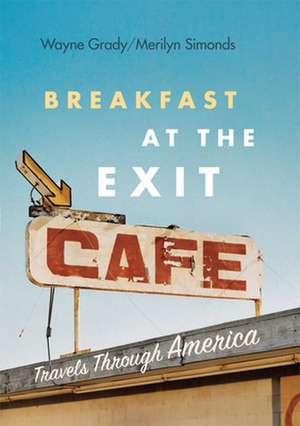

Breakfast at the Exit Cafe: Travels Through America

Autor Wayne Grady, Merilyn Simondsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 aug 2011

What begins as a road trip through America soon becomes a journey of discovery into themselves and into the heart of the next-door neighbour they thought they knew. For Wayne Grady, the thrill of landscape and history is tempered by memories of racism and his own family roots. Merilyn Simonds, her ear tuned for the offbeat, finds curious echoes of the ex-pat promised land she grew up with. Together they travel against the tide of American history, following in the literary tire tracks of John Steinbeck, William Least Heat Moon, and Francis Trollope.

Grady and Simonds experience the splendors of the Mojave Desert, the Grand Canyon, the Mississippi River, and the bayou’s of Louisiana and the Outer Banks and contemplate the impact of geography on culture and of culture on landscape. They observe America from the outside, yet feel strangely at home.

Part travelogue, part exploration, part mid-winter love story told with wit and acuity by one of Canada’s most engaging literary couples, Breakfast at the Exit Cafe is a journey into the reality behind the cultural myth that is America.

Grady and Simonds experience the splendors of the Mojave Desert, the Grand Canyon, the Mississippi River, and the bayou’s of Louisiana and the Outer Banks and contemplate the impact of geography on culture and of culture on landscape. They observe America from the outside, yet feel strangely at home.

Part travelogue, part exploration, part mid-winter love story told with wit and acuity by one of Canada’s most engaging literary couples, Breakfast at the Exit Cafe is a journey into the reality behind the cultural myth that is America.

Preț: 68.55 lei

Preț vechi: 84.32 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 103

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.12€ • 14.26$ • 11.03£

13.12€ • 14.26$ • 11.03£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781553658269

ISBN-10: 1553658264

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:None.

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Locul publicării:Canada

ISBN-10: 1553658264

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:None.

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Locul publicării:Canada

Cuprins

Preface 1

1 / Megalopolis, usa 3

2 / Astoria 28

3 / Highway 101 50

4 / Eureka! California 68

5 / Route 66 85

6 / Grand Canyon, Arizona 105

7 / The Marriage Road 130

8 / Escalante, Utah 153

9 / El Camino Real 177

10 / Jefferson, Texas 207

11 / Selmalabama 233

12 / Athens, Georgia 260

13 / The Outer Banks 282

14 / The Exit Cafe 307

Acknowledgements 317

1 / Megalopolis, usa 3

2 / Astoria 28

3 / Highway 101 50

4 / Eureka! California 68

5 / Route 66 85

6 / Grand Canyon, Arizona 105

7 / The Marriage Road 130

8 / Escalante, Utah 153

9 / El Camino Real 177

10 / Jefferson, Texas 207

11 / Selmalabama 233

12 / Athens, Georgia 260

13 / The Outer Banks 282

14 / The Exit Cafe 307

Acknowledgements 317

Recenzii

"Like the great travel writers before them, Grady and Simonds entertain and enlighten in a foreign yet familiar world—a brilliant road trip I didn’t want to end."—Joseph Boyden, author of Three Day Road

"Grady and Simonds bring their well-honed cultural and literary sensibilities to bear on a revealing road trip"—Ronald Wright, author of What is America?

“the narrative in Breakfast at the Exit Cafe flows as easily as a new car on an empty highway”—Globe & Mail Top 100 for 2010

"Grady and Simonds bring their well-honed cultural and literary sensibilities to bear on a revealing road trip"—Ronald Wright, author of What is America?

“the narrative in Breakfast at the Exit Cafe flows as easily as a new car on an empty highway”—Globe & Mail Top 100 for 2010

Notă biografică

Wayne Grady is one of Canada's finest science writers and a Governor General's Award-winning translator. He has authored eleven books of nonfiction, translated fourteen novels, and edited more than a dozen anthologies of short stories and creative nonfiction.

Merilyn Simonds is the author of fourteen books, including the novel The Holding, named a New York Times Editor's Choice, as well as the acclaimed works of literary nonfiction The Lion in the Room Next Door and The Convict Lover, a finalist for the Governor General's Award.

Merilyn Simonds is the author of fourteen books, including the novel The Holding, named a New York Times Editor's Choice, as well as the acclaimed works of literary nonfiction The Lion in the Room Next Door and The Convict Lover, a finalist for the Governor General's Award.

Extras

from Chapter 5: Route 66

When people are asked to name a famous American highway, chances are they’ll say Route 66. I first heard of it in the 1960s, on the television series Route 66, starring George Maharis and Martin Milner as two young boyos travelling around America in a Corvette. Before that, the road was immortalized by John Steinbeck in the 1930s, by Nat King Cole in the ’40s, and by Jack Kerouac in the ’50s. The long, meandering highway was begun in 1925 to forge a continuously paved link between Chicago, Illinois, and Barstow, California, joining hundreds of hitherto disconnected small towns and dirt back roads, following river and even creek beds, heeding its own serendipitous logic as it sifted down through Arkansas and Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle before finally swinging west through New Mexico and Arizona. It was finished in 1934, just in time for the exodus of Oklahoma farmers heading to California in search of a new beginning. “The mother road,” John Steinbeck called it. “The road of flight.”

At Barstow we leave Highway 58 and get on the I-40, which has obliterated the Mother Road across much of America. Although the I-40 bears little resemblance to that mythical highway of the 1930s, it’s still a prepossessing ribbon of daylight, threading the Mojave Desert, lined with cactus and mesquite. Not a place to run out of gas, get a flat tire, or have an argument with your wife. As I recall, there are no knock-down, drag-out fights between the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath. Driving through country like this gives you a firm grasp on what’s important.

It certainly did for Steinbeck. The vast, westward migration of some 250,000 destitute farm workers became his life’s subject. In 1936, he was hired by the San Francisco News to write a seven-part feature about the massive influx of American migrant workers into the Central Valley. He called the series “The Harvest Gypsies,” and although it began as an objective report on the plight of the homeless and the helpless, it quickly became a polemic against the industrialized agricultural system that flourished as a result of engineered water and economies of scale, a system that reaped huge profits for owners but paid migrant workers starvation wages and brutally punished anyone who even thought about forming a farm workers’ union (which Cesar Chavez finally achieved in 1966).

“It is difficult to believe,” Steinbeck wrote in that series, “what one large speculative farmer has said, that the success of California agriculture requires that we create and maintain a peon class. For if this is true, then California must depart from the semblance of democratic government that remains here.”

In Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck often steps outside the fictional world of the Joad family to present detailed descriptions of Highway 66, as well as first-person chapters by used-car salesmen or truck-stop waitresses. These realistic riffs were Steinbeck’s way of bringing his readers to the understanding that what they were reading was not fiction invented out of thin air by an abstract artist, but a true account of a serious crisis in American history. By putting a face on the working class, he paved the way for the eventual success of Chavez and the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee in their struggle for human rights. It is fitting that when Chavez went on a hunger strike to protest migrant workers’ living conditions in 1968, he received a letter of support from Martin Luther King, Jr. Among King’s last public words before his assassination was the verse “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” with its implied next line: “He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

When the Joads crossed the Colorado River in their overloaded Hudson truck, they looked down on the section of California through which we’re now travelling. They saw little but “broken, rotten rock winding and twisting through dead country, burned white and grey, and no life in it.” The landscape hasn’t changed. I wouldn’t say there is no life in it, but it is certainly diminished life, toehold life, life the Joads must have understood.

Near the Pisgah Crater, we turn into what looks like an abandoned quarry or an open-pit salt mine, with a dirt track running down into a hole carved through an exposure of reddish-brown stone. Thick thorn bushes cover most of the ground. We get out and pick our way through them to the top of the quarry to look southwest, toward the setting sun. The sand still holds some heat from the day, and although a cool breeze is coming at us over the desert, we are not cold. We can hear birds, tiny peeps and quiet, cricket-like flock calls, a small family group making its way through the low shrubs and grasses, but we cannot see them.

Merilyn and I separate for a while, the first time we’ve been out of each other’s sight for days, and I find a small cup-nest set deep in a leafless Anderson thornbush that must be that of a cactus wren, a wren the size of a robin (most wrens are not much bigger than chickadees) that I would very much like to see. But there is no sign that the nest has been used lately. I call Merilyn over, and she reaches delicately into the thornbush, extracts a dun-coloured feather, and hands it to me, a gift. It is, after all, Christmas Eve.

Much about this parched interior landscape seems familiar. I’ve never been here before, but staring through the windshield at the empty desert, I realize I’ve been seeing it all my adult life, in the photographs of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank.

I reach back into the rubble of the back seat and lift out the camera.

“Want me to stop?” Wayne asks.

“No,” I say. “I’ll just roll down my window.”

In the latter half of the Thirties, the Farm Security Administration hired some of the best photographers of the day—Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, Walker Evans—to roam the country, documenting the devastation wrought by the drought. The photographers were sent out with detailed shooting scripts: “Crowded cars going out on the open road. Gas station attendant filling tank of open touring and convertible cars.” The kind of pictures I like to take.

Walker Evans had already compiled his own list of picture categories, which rivals Jefferson’s directive to Lewis and Clark in ambition and scope. It’s a useful list for any traveller out to understand a country:

When people are asked to name a famous American highway, chances are they’ll say Route 66. I first heard of it in the 1960s, on the television series Route 66, starring George Maharis and Martin Milner as two young boyos travelling around America in a Corvette. Before that, the road was immortalized by John Steinbeck in the 1930s, by Nat King Cole in the ’40s, and by Jack Kerouac in the ’50s. The long, meandering highway was begun in 1925 to forge a continuously paved link between Chicago, Illinois, and Barstow, California, joining hundreds of hitherto disconnected small towns and dirt back roads, following river and even creek beds, heeding its own serendipitous logic as it sifted down through Arkansas and Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle before finally swinging west through New Mexico and Arizona. It was finished in 1934, just in time for the exodus of Oklahoma farmers heading to California in search of a new beginning. “The mother road,” John Steinbeck called it. “The road of flight.”

At Barstow we leave Highway 58 and get on the I-40, which has obliterated the Mother Road across much of America. Although the I-40 bears little resemblance to that mythical highway of the 1930s, it’s still a prepossessing ribbon of daylight, threading the Mojave Desert, lined with cactus and mesquite. Not a place to run out of gas, get a flat tire, or have an argument with your wife. As I recall, there are no knock-down, drag-out fights between the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath. Driving through country like this gives you a firm grasp on what’s important.

It certainly did for Steinbeck. The vast, westward migration of some 250,000 destitute farm workers became his life’s subject. In 1936, he was hired by the San Francisco News to write a seven-part feature about the massive influx of American migrant workers into the Central Valley. He called the series “The Harvest Gypsies,” and although it began as an objective report on the plight of the homeless and the helpless, it quickly became a polemic against the industrialized agricultural system that flourished as a result of engineered water and economies of scale, a system that reaped huge profits for owners but paid migrant workers starvation wages and brutally punished anyone who even thought about forming a farm workers’ union (which Cesar Chavez finally achieved in 1966).

“It is difficult to believe,” Steinbeck wrote in that series, “what one large speculative farmer has said, that the success of California agriculture requires that we create and maintain a peon class. For if this is true, then California must depart from the semblance of democratic government that remains here.”

In Grapes of Wrath, Steinbeck often steps outside the fictional world of the Joad family to present detailed descriptions of Highway 66, as well as first-person chapters by used-car salesmen or truck-stop waitresses. These realistic riffs were Steinbeck’s way of bringing his readers to the understanding that what they were reading was not fiction invented out of thin air by an abstract artist, but a true account of a serious crisis in American history. By putting a face on the working class, he paved the way for the eventual success of Chavez and the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee in their struggle for human rights. It is fitting that when Chavez went on a hunger strike to protest migrant workers’ living conditions in 1968, he received a letter of support from Martin Luther King, Jr. Among King’s last public words before his assassination was the verse “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord,” with its implied next line: “He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.”

When the Joads crossed the Colorado River in their overloaded Hudson truck, they looked down on the section of California through which we’re now travelling. They saw little but “broken, rotten rock winding and twisting through dead country, burned white and grey, and no life in it.” The landscape hasn’t changed. I wouldn’t say there is no life in it, but it is certainly diminished life, toehold life, life the Joads must have understood.

Near the Pisgah Crater, we turn into what looks like an abandoned quarry or an open-pit salt mine, with a dirt track running down into a hole carved through an exposure of reddish-brown stone. Thick thorn bushes cover most of the ground. We get out and pick our way through them to the top of the quarry to look southwest, toward the setting sun. The sand still holds some heat from the day, and although a cool breeze is coming at us over the desert, we are not cold. We can hear birds, tiny peeps and quiet, cricket-like flock calls, a small family group making its way through the low shrubs and grasses, but we cannot see them.

Merilyn and I separate for a while, the first time we’ve been out of each other’s sight for days, and I find a small cup-nest set deep in a leafless Anderson thornbush that must be that of a cactus wren, a wren the size of a robin (most wrens are not much bigger than chickadees) that I would very much like to see. But there is no sign that the nest has been used lately. I call Merilyn over, and she reaches delicately into the thornbush, extracts a dun-coloured feather, and hands it to me, a gift. It is, after all, Christmas Eve.

Much about this parched interior landscape seems familiar. I’ve never been here before, but staring through the windshield at the empty desert, I realize I’ve been seeing it all my adult life, in the photographs of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank.

I reach back into the rubble of the back seat and lift out the camera.

“Want me to stop?” Wayne asks.

“No,” I say. “I’ll just roll down my window.”

In the latter half of the Thirties, the Farm Security Administration hired some of the best photographers of the day—Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Russell Lee, Walker Evans—to roam the country, documenting the devastation wrought by the drought. The photographers were sent out with detailed shooting scripts: “Crowded cars going out on the open road. Gas station attendant filling tank of open touring and convertible cars.” The kind of pictures I like to take.

Walker Evans had already compiled his own list of picture categories, which rivals Jefferson’s directive to Lewis and Clark in ambition and scope. It’s a useful list for any traveller out to understand a country:

People, all classes, surrounded by bunches of the new down-and-out

Automobiles and the automobile landscape

Architecture, American urban taste, commerce, small scale, large scale, clubs, the city atmosphere, the street smell, the hateful stuff, women’s clubs, fake culture, bad education, religion in decay

The movies

Evidence of what people of the city read, eat, see for amusement, do for relaxation and not get it

Sex

Advertising

A lot else, you see what I mean.

Automobiles and the automobile landscape

Architecture, American urban taste, commerce, small scale, large scale, clubs, the city atmosphere, the street smell, the hateful stuff, women’s clubs, fake culture, bad education, religion in decay

The movies

Evidence of what people of the city read, eat, see for amusement, do for relaxation and not get it

Sex

Advertising

A lot else, you see what I mean.