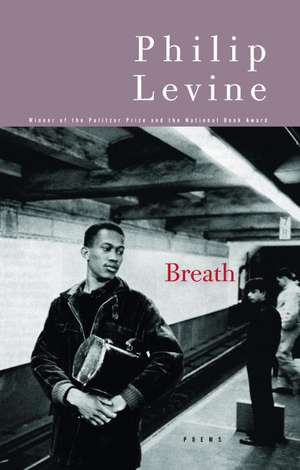

Breath: Poems

Autor Philip Levineen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2005

Throughout the collection Levine rejoices in song–Dinah Washington wailing from a jukebox in midtown Manhattan; Della Daubien hymning on the crosstown streetcar; Max Roach and Clifford Brown at a forgotten Detroit jazz palace; the prayers offered to God by an immigrant uncle dreaming of the Judean hills; the hoarse notes of a factory worker who, completing another late shift, serenades the sleeping streets.

Like all of Levine’s poems, these are a testament to the durability of love, the strength of the human spirit, the persistence of life in the presence of the coming dark.

Preț: 90.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 135

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.24€ • 18.72$ • 14.48£

17.24€ • 18.72$ • 14.48£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375710780

ISBN-10: 0375710787

Pagini: 82

Dimensiuni: 145 x 224 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

ISBN-10: 0375710787

Pagini: 82

Dimensiuni: 145 x 224 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

Notă biografică

Philip Levine is the author of sixteen collections of poems and two books of essays. He has received many awards for his poetry, including the National Book Award in 1980 for Ashes and again in 1991 for What Work Is, and the Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for The Simple Truth. He divides his time between Brooklyn, New York, and Fresno, California.

Philip Levine’s The Mercy, New Selected Poems, The Simple Truth, and What Work Is are available in Knopf paperback.

From the Hardcover edition.

Philip Levine’s The Mercy, New Selected Poems, The Simple Truth, and What Work Is are available in Knopf paperback.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Lesson

Early in the final industrial century

on the street where I was born lived

a doctor who smoked black shag

and walked his dog each morning

as he muttered to himself in a language

only the dog knew. The doctor had saved

my brother’s life, the story went, reached

two stained fingers down his throat

to extract a chicken bone and then

bowed to kiss the ring--encrusted hand

of my beautiful mother, a young widow

on the lookout for a professional.

Years before, before the invention of smog,

before Fluid Drive, the eight-hour day,

the iron lung, I'd come into the world

in a shower of industrial filth raining

from the bruised sky above Detroit.

Time did not stop. Mother married

a bland wizard in clutch plates

and drive shafts. My uncles went off

to their world wars, and I began a career

in root vegetables. Each morning,

just as the dark expired, the corner church

tolled its bells. Beyond the church

an oily river ran both day and night

and there along its banks I first conversed

with the doctor and Waldo, his dog.

"Young man," he said in words

resembling English, "you would dress

heavy for autumn, scarf, hat, gloves.

Not to smoke," he added, "as I do."

Eleven, small for my age but ambitious,

I took whatever good advice I got,

though I knew then what I know

now: the past, not the future, was mine.

If I told you he and I became pals

even though I barely understood him,

would you doubt me? Wakened before dawn

by Catholic bells, I would dress

in the dark -- remembering scarf, hat, gloves --

to make my way into the deserted streets

to where Waldo and his master ambled

the riverbank. Sixty-four years ago,

and each morning is frozen in memory,

each a lesson in what was to come.

What was to come? you ask. This world

as we have it, utterly unknowable,

utterly unacceptable, utterly unlovable,

the world we waken to each day

with or without bells. The lesson was

in his hands, one holding a cigarette,

the other buried in blond dog fur, and in

his words thick with laughter, hushed,

incomprehensible, words that were sound

only without sense, just as these must be.

Staring into the moist eyes of my maestro,

I heard the lost voices of creation running

over stones as the last darkness sifted upward,

voices saddened by the milky residue

of machine shops and spangled with first light,

discordant, harsh, but voices nonetheless.

From the Hardcover edition.

Early in the final industrial century

on the street where I was born lived

a doctor who smoked black shag

and walked his dog each morning

as he muttered to himself in a language

only the dog knew. The doctor had saved

my brother’s life, the story went, reached

two stained fingers down his throat

to extract a chicken bone and then

bowed to kiss the ring--encrusted hand

of my beautiful mother, a young widow

on the lookout for a professional.

Years before, before the invention of smog,

before Fluid Drive, the eight-hour day,

the iron lung, I'd come into the world

in a shower of industrial filth raining

from the bruised sky above Detroit.

Time did not stop. Mother married

a bland wizard in clutch plates

and drive shafts. My uncles went off

to their world wars, and I began a career

in root vegetables. Each morning,

just as the dark expired, the corner church

tolled its bells. Beyond the church

an oily river ran both day and night

and there along its banks I first conversed

with the doctor and Waldo, his dog.

"Young man," he said in words

resembling English, "you would dress

heavy for autumn, scarf, hat, gloves.

Not to smoke," he added, "as I do."

Eleven, small for my age but ambitious,

I took whatever good advice I got,

though I knew then what I know

now: the past, not the future, was mine.

If I told you he and I became pals

even though I barely understood him,

would you doubt me? Wakened before dawn

by Catholic bells, I would dress

in the dark -- remembering scarf, hat, gloves --

to make my way into the deserted streets

to where Waldo and his master ambled

the riverbank. Sixty-four years ago,

and each morning is frozen in memory,

each a lesson in what was to come.

What was to come? you ask. This world

as we have it, utterly unknowable,

utterly unacceptable, utterly unlovable,

the world we waken to each day

with or without bells. The lesson was

in his hands, one holding a cigarette,

the other buried in blond dog fur, and in

his words thick with laughter, hushed,

incomprehensible, words that were sound

only without sense, just as these must be.

Staring into the moist eyes of my maestro,

I heard the lost voices of creation running

over stones as the last darkness sifted upward,

voices saddened by the milky residue

of machine shops and spangled with first light,

discordant, harsh, but voices nonetheless.

From the Hardcover edition.