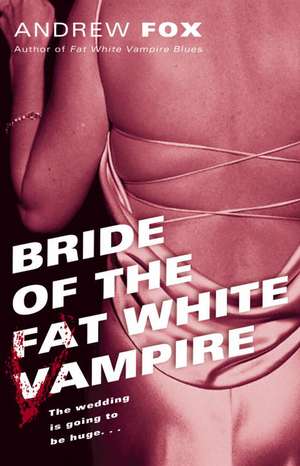

Bride of the Fat White Vampire: Fat White Vampire

Autor Andrew Foxen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2004 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

What’s a vampire to do? Without the love of a woman to ease his pain, Jules isn’t convinced that his undead life is worth living. He doesn’t desire Doodlebug (she may be a woman now but Jules knew her back when she was just a boy) any more than he longs for Daphne, a rat catcher who nourishes a crush the size of Jules. No, only Maureen will do. Once a beautiful stripper with nothing but curve after curve to her bodacious body, now she is mere dust in a jar. But Jules will move heaven and earth to get her back . . . even if it means pulling her back from the dead.

Preț: 112.81 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.59€ • 22.54$ • 17.87£

21.59€ • 22.54$ • 17.87£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345464088

ISBN-10: 0345464087

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Fat White Vampire

ISBN-10: 0345464087

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Fat White Vampire

Extras

ONE Rory “Doodlebug” Richelieu shivered as he walked up the dark gravel path toward the fifteen-foot-high walls surrounding the High Krewe’s compound. A vampire shouldn’t be afraid of the dark, he told himself. Yet the short walk from where a cab had let him off on Metairie Road through these gloomy woods, barely lit by a weak moon, had seriously creeped him out. He wished he’d worn a shawl. His lightweight linen dress and lace hosiery were fine for the Quarter, but here they left him feeling chilled. And the heels of his pumps sank into the gravel, nearly causing him to twist an ankle several times.

When he was ten feet from the gate, something scurried near his feet. He saw something run into the underbrush, a mouse or squirrel or maybe a small rat. Doodlebug smiled a wistful smile. The tiny mammal had made him think of Jules. As he had innumerable times during the past eight months, Doodlebug wondered how the Fates had been treating his vanished friend. He hoped with all his heart that Jules had found happiness.

The iron gates towered before him like the entrance to one of Dante’s inner circles of Hell. Doodlebug pressed the cold steel button that protruded from the marble gatepost. A disguised panel slid open, revealing a video screen. A dignified, somewhat haughty face appeared; a computer-generated image, Doodlebug realized, since the butler was himself a vampire and could not be photographed. Above him, at the top of the entrance archway, a small camera tracked his movements. All it would reveal to the viewer on the other end was a knee-length black dress, pale ivory lace hosiery, sensible black pumps, earrings, and lipstick of a modest shade of red.

“I’m Rory Richelieu,” Doodlebug said. It felt odd to call himself by his birth name; normally he went by Debbie, and whenever he’d returned to New Orleans to see Jules or Maureen, he’d always slipped back into his childhood nickname, Doodlebug. “I flew out from California. Georges Besthoff asked me to come.” Asked was too pale a word; demanded was more like it.

The face on screen appeared to be examining a list. “Yes. Mr. Richelieu. I’ve been told to expect you. Master Besthoff is awaiting you in the library.”

The massive iron gate swung open as smoothly and silently as silk on silk. The scent of pomegranates reached him on a cool breeze. Blood apples. High above, at the center of a cloud-dimpled sky, a half-moon illuminated stately groves and manicured gardens, all of which would appear quite at home surrounding the ancient fortress-estates of Moravia or Romania. Doodlebug had not set foot within the gates of the compound of the High Krewe of Vlad Tepes in decades. Not since 1968, just after he’d completed his thirteen years of study in Tibet, when he’d been planning to leave New Orleans for California to establish his Institute of Higher Alpha-Consciousness.

As grand and beautiful as this walled assemblage of mansions and gardens was, he’d never felt any fondness for this place. Most of the vampires here were far older than he was, immigrants from Eastern Europe, one of the cultural hearts of world vampirism, and had amassed their impressive fortunes over hundreds of years. The wisdom of their collective centuries had not brought them enlightenment, as it had to Doodlebug’s Tibetan monk teachers; instead, it had taught them to pursue their own narrow interests with scientific precision. As a fledgling vampire, he’d considered himself a catfish among tiger sharks in his dealings with the masters of this place. He’d always suspected they’d granted their support to his California project only because they’d judged him to be an interesting, potentially useful freak.

Doodlebug hadn’t heard a peep from the High Krewe’s masters in a quarter century. What did they want with him now? Besthoff certainly hadn’t ordered him to fly across the continent for a social call. He had been infuriatingly evasive in his communiqués, as he always was. But he’d left no doubt that he was willing to pound the stake through Doodlebug’s most precious aspirations if Doodlebug failed to comply.

Doodlebug walked briskly past fountains illuminated with beams of green, red, and white, the colors of the old Hungarian monarchy. He sensed an unfamiliar dampness under his smooth arms, despite the chill in the air; he was thankful that he’d chosen to wear black. Apprehensive as he was about the nature of his mysterious task, he was eager to get the undoubtedly sordid business over with as quickly as possible.

He climbed the broad marble stairs that led to the compound’s central building, an Italianate mansion easily twice as large as the grandest home on St. Charles Avenue. Twin twelve-foot-high doors opened soundlessly before he could knock.

“Mr. Richelieu. Welcome. It is a pleasure to see you again after all these years.”

The sentiment sounded as sincere as a local politician’s promises to fix the potholes. Doodlebug stared up at the long, sallow face of Straussman the butler. He was even haughtier and more austere than his computer-generated image; Doodlebug, an avid fan of the films of the forties, thought Straussman made Erich von Stroheim look like Lou Costello. Nevertheless, he smiled and answered Straussman’s stiff bow with a polite curtsy.

“Thank you, Straussman. The years have been good to you.”

“You are too kind, sir.”

Straussman closed the doors, polished oak eight-inches thick, with little discernible effort. “Please allow me to escort you to the library.”

They left the entrance foyer and entered a tall, wide hallway decorated with tapestries large enough to cloak elephants. Doodlebug remembered these tapestries well. Each depicted a victory of King Vlad Tepes over the marauding Turks, who were portrayed as beasts with barely human features. The largest of the tapestries showed Vlad Tepes holding court in front of a panorama of severed Turkish heads impaled on tall wooden spikes.

Just before they reached the library, Straussman paused and turned back toward Doodlebug. “We have been experiencing unsettled times within our household,” he said in a low voice, almost a whisper. Doodlebug detected a slight change in his normally imperturbable face, a hint of what might almost pass for concern. “The young masters . . .” His voice trailed off. It was fascinating and unsettling to watch Straussman struggle for words. “I do hope, sir, that you will be able to assist Master Besthoff in bringing certain matters to a satisfactory close. Bringing certain . . . foul parties to the justice they richly deserve.”

Then he turned away again, and Doodlebug watched him straighten his neck and torso to their habitual lacquered stiffness before he opened the doors of the library. “Master Besthoff,” he said, “if you would kindly forgive the intrusion, I have the pleasure of presenting Mr. Rory Richelieu.”

“Thank you, Straussman,” a deep, fine-grained voice, tinged slightly with a Rumanian accent, answered. “You may show him in.”

Doodlebug hurriedly smoothed the wrinkles from his dress and entered the library. Of all the compound’s hundreds of rooms, this was the one that had always fascinated him the most. He was greeted by a seductive perfume of polished teak and aged paper. His mouth fell open as he craned his neck to take in the thousands of volumes, most of them more than a century old. The inhabitants of this compound had millions of empty hours to fill, particularly since they had “advanced beyond the primitive hunting and gathering stage,” to use Besthoff’s memorable phrase. What better place to spend some of those millions of hours than this cathedral of literature, open all night long?

However, apart from Doodlebug and Straussman, who hovered near the entrance in readiness for additional tasks, the library held only one occupant. Georges Besthoff sat in a high-backed, gilded Queen Anne chair beside a tall Tiffany lamp and a coffee table decorated with the wings and clawed feet of a gryphon. He was as tall as Straussman, but far broader through the chest. Untold centuries in age, he didn’t appear any older than his midforties, with only an occasional strand of silver flashing within the midnight blackness of his immaculately groomed hair. His eyes were coals that had been compressed by unnatural gravity into onyx diamonds, glowering with negative light.

Doodlebug frowned slightly as he remembered how Besthoff and the others had built their fortunes in Europe. Among the oldest of that region’s vampires, they had gradually seduced many of the neighboring noble families into the blood-sucking fraternity, convincing them to leave one aristocracy for another; then they had taken advantage of the nouveau vampires’ junior status to appropriate portions of their holdings. If it hadn’t been for the antiroyal revolutions of 1848, Besthoff, Katz, and Krauss would never have left the enriching embrace of their ancestral lands for New Orleans.

Besthoff’s smile was well rehearsed, the practiced smile of a diplomat from the age of dynastic empires. “Mr. Richelieu,” he said, gesturing for him to sit in the chair on the far side of the gryphon table, “I believe the last time you visited us, that Texan excrescence, Lyndon Johnson, was still in the White House. It has been too long.” He looked Doodlebug over with a coolly appraising glance, his eyes lingering on the swellings of his guest’s hips and bustline. “I see that you have honed your talents considerably since the last time we met. Were I ignorant of your natural sex, I would be most aroused by your display of lush, young femininity.”

Doodlebug felt hot blood rush into his face. It wasn’t a sensation he felt often. He’d grown used to being around people who accepted him as a woman, who didn’t know differently. Now, in the presence of this man who knew him to be a fellow man, who could take away his independence with the snap of his fingers, Doodlebug experienced for the first time the sense of relative powerlessness that so many women suffered. “Maintaining continual control over my form,” he said too quickly, “is a useful exercise in spiritual discipline.”

“Yes,” Besthoff said, smiling. He interlocked his long fingers, flex- ing the powerful muscles of his hands. “That must be so, I am sure.” He glanced toward Straussman and signaled with a slight tilt of his head that the butler should attend to him. “But I forget my obligations as host. You are famished after your long air journey. All those distressing changes in air pressure. Would you prefer blood or a glass of wine?”

Doodlebug took a moment to consider this. With men such as Besthoff, there were no gifts; accepting even the smallest of boons meant allowing the cords of obligation to be pulled ever tighter. There was good reason he’d air-shipped his coffin and a week’s supply of blood to a New Orleans bed-and-breakfast inn where he’d stayed before, rather than accept Besthoff’s offer of lodging in the mansion. Truthfully, a long drink of the life-giving ichor would restore his strength and possibly settle his nerves. But he couldn’t bury the thought that the less obligated he was to the High Krewe, the better off he’d be.

“Well?” Besthoff said, raising an eyebrow, a hint of amusement in his dark eyes. “What will you have, Mr. Richelieu?”

“A pot of herbal tea would be lovely,” Doodlebug said. He glanced up at Straussman’s unreadable face. “Could you fix me some chamomile?”

“I will check the pantry, sir,” Straussman said.

“Very well,” Besthoff said. He frowned and waved Straussman away. “Bring me my usual midevening cocktail.” He turned back to his guest. “How fares your Institute?” he asked, a polite smile reaffixed upon his predatory face.

To Doodlebug’s ears, his host’s expression of interest was wrapped around a core of cold condescension. It wasn’t at all surprising that, after Doodlebug declined his host’s offer of blood, Besthoff would focus on the vulnerability that granted him the greatest degree of leverage over his guest. Doodlebug closed his eyes for a second and attempted to picture a perfectly calm sea. “It fares very well, thank you,” he said, his eyes open again. “I currently have forty-two students. Twenty-three reside on my campus. The others commute from surrounding towns.”

“So the passion for Eastern mysticism has not subsided in your part of the country?”

“Apparently not, no.”

“Your students,” Besthoff continued, “they still make their monthly ‘donations’ of blood during their periods of study?”

“Every six weeks, yes. It’s part of their cycle of cleansing and purification. All of my students are strict vegetarians. The blood-letting complements their regimens of fasting and ascetic yoga.”

“Very clever,” Besthoff said, a hint of genuine admiration in his voice. “I always expected that our investment would return interesting dividends. Have any of your students expressed any opinions regarding this regimen of ‘blood-letting,’ as you call it? Do you think they suspect vampirism might be the motivating factor?”

“California is different from the rest of the country,” Doodlebug said, shifting in his seat. He pulled the edges of his dress well below his knees, then chided himself for doing so. “A combination of widespread Wiccanism and Hollywood liberalism means that blood-drinking is not as stigmatized as it would be here. All that aside, my students accept me as what I present myself to be—a spiritual mentor and a fellow learner. I’ve never overheard any whisperings of vampirism. Such suspicion and distrust are the opposite of all that my students seek to achieve.”

“Yes. Of course.” Straussman returned with a silver tray. A white china teapot, embossed with twirling roses, emitted a strong aroma of Earl Grey through its spout. Oh, well, Doodlebug thought. Close enough. Straussman set the tray down on the gryphon table and served Besthoff his cocktail, which, Doodlebug guessed from its scent, was a mixture of sherry and blood.

Besthoff took a sip of his cocktail and eyed Doodlebug evenly over the rim of the expansive goblet. “Would you expand the Institute, if you were able? Do you feel you could attract a larger number of students?”

“It’s . . . possible,” Doodlebug said, measuring his words carefully. What was Besthoff driving at? “Although I couldn’t handle many more students myself. If I allowed more students in, I’d need to train additional instructors. Additional instructors would require expanding my physical plant.”

“That could potentially be arranged.” Doodlebug felt Besthoff’s eyes drilling into his. The tall man set down his goblet and leaned closer. “Our household has been experiencing some disquietude of late. Some of the younger members have begun to . . . chafe within what they feel to be unreasonable restrictions on their liberties. You were once the child protégé of that Duchon person, were you not?”

The mention of Jules’s name brought a flood of memories. Only eight months had passed since he’d taught his friend and blood-father the skills he needed to overcome the deadly challenge posed by a group of new, young black vampires.

The distaste in Besthoff’s voice when he uttered Jules’s name was unmistakable. “Yes,” Doodlebug said. “Jules turned me in 1943, during the war. He wanted a sidekick to help him protect New Orleans’s munitions plants from Nazi saboteurs.”

“But you did not stay with him long after the war was over, did you? You began your spiritual quest, which eventually led you to Tibet. Correct?”

“That’s true. But I might have stayed longer with Jules in New Orleans if he hadn’t been so uncomfortable with my, ah, proclivities.” Doodlebug stared at the crimson-painted nails that adorned his slender fingers, now interlaced tightly on his lap.

“In any case, I expect you have some understanding of the rebellious impulses that often accompany youth. A need to break away from the often sensible lifestyle of one’s elders, to establish one’s own identity and autonomy.”

“That’s a common preoccupation of youth in all societies. Even vampiric ones. It’s not unhealthy.”

“In many cases, perhaps.” Besthoff took another sip from his goblet. He let it linger in his mouth before swallowing. “But in the case of my little society, my High Krewe, youthful rebellion and indiscretion have led to outcomes most unhealthy.” The dark red tip of his tongue brushed his lower lip. “Tragic outcomes. Events which I deeply regret, and which I cannot allow to go unaddressed.”

Doodlebug waited for him to continue. He picked up the cup of tea Straussman had poured for him. The liquid burned the roof of his mouth.

“I will speak more of this in a moment,” Besthoff said after many long seconds. “The restless energies of youth are difficult to contain, even in the face of tragedy. I may need to find a safe haven for several of our youngsters away from this compound, in a place where they can feel they have broken away from the nest, and so will not be tempted into dangerous pursuits. I believe your Institute would be an ideal place for them to ‘find themselves’ without endangering themselves.”

Doodlebug’s face tightened as the reason for his summons to the compound of the High Krewe of Vlad Tepes became clear. The Krewe had never interfered in his running of the Institute before. They’d never had reason to. Until now. But now, from the sound of things, he was expected to take in a bunch of spoiled, aristocratic vampires, most of whom probably had zero interests outside of sex, leisure, and a good meal, and try to guide them on a path toward enlightenment. “You want me to take them on as students? How would I keep them fed? Even with strict rationing, the blood donations provided by my current students would barely sustain me and one other vampire.”

“I don’t expect you to take them on as students,” Besthoff said. “I expect you to take them on as instructors. Each will need to be provided with a complement of students adequate to supply him with a steady diet. The High Krewe will provide financial support for the construc- tion of expanded facilities, advertising to attract additional students, et cetera.”

Doodlebug’s alabaster skin turned a sicklier shade of white. His dream. The great spiritual project that gave his undead existence meaning. They wanted to pervert it, to take it in their filthy hands and reshape it in their own cruel, selfish image. He’d known, of course, when he’d first acquired the monumental loan from the High Krewe to buy his twenty-five acres of oceanfront property and construct his austere campus, that a quid pro quo was likely. But he’d spent decades avoiding that possibility, pushing it into the dustiest corners of his mind.

“You ask . . . very much of me,” he managed to say at last. “This is the reason you demanded I come here? To recruit your youngsters?”

Besthoff smiled tightly. “Not exactly, no. That is more of a long-term goal. I recognize that such arrangements as I have spoken of will take time. You will need to make plans. The more restless youngsters will need to be convinced that a move to Northern California is indeed what they want.”

Besthoff stood, rising to his imposing full height of six feet and five inches. “No, Mr. Richelieu, the reason I had you come is far more pressing. Follow me, please. What I am about to show you will make my needs and your responsibility abundantly clear.”

He walked to the library’s entrance. Doodlebug set his teacup down (caffeine was the last thing he needed at this point, anyway) and followed. Besthoff motioned for Straussman to accompany them. The butler opened a set of tall French doors that led to a courtyard of formal gardens and hedges trimmed as exactingly as a nobleman’s mustache.

At the far end of the gardens, beyond the ponderous wings of the main mansion, sat a separate building much more plain and simple than the one Doodlebug had just left. Not that it was not ornate; it reminded Doodlebug of the redbrick Catholic schoolhouse he’d attended before he’d met Jules. They climbed three steps to a broad porch lined with white wooden posts. Straussman removed a large ring of keys from his coat pocket and unlocked the door.

They stepped inside the entrance foyer, and Straussman locked the door behind them. Doodlebug crinkled his elfin nose. The odor he smelled wasn’t repulsive, at least not overwhelmingly so. He remembered the odor from years ago, when he’d been a small child and a broken arm had landed him within the crowded wards of Charity Hospital for a week. It was the collective scent of dozens of people who spent their days and nights confined to bed, who bathed infrequently and changed their garments less often than they bathed and who relieved themselves in bed pans.

“You may remember our farm,” Besthoff said. “I can’t recall whether I granted you a tour the last time you visited.”

“I’ve never been inside here, no,” Doodlebug said.

“But you’re aware of the economic underpinnings of our compound, of course? Our blood-cows?”

Blood-cows. Doodlebug frowned slightly. It didn’t seem right to refer to human beings that way. Not even human beings of the sort who lived here. “So this is where the, uh, mentally handicapped individuals are cared for?”

“Yes.” He gestured for Straussman to turn on the lights in the next room. “Please forgive the slight stench. Over the past year, it has become harder and harder to get our young people to fulfill their obligations here. We threaten them with cutting back on their blood rations if they miss shifts. But one can only take such threats so far without it becoming counterproductive. And Straussman and the other household staff are limited in how much time they can take from their primary duties to tidy up here.”

They walked into the main room. The building was much deeper than it had looked from the outside, Doodlebug realized. This dormitory contained four rows of thirty beds each; the beds were about eighteen inches apart, and the aisles between rows allowed two people abreast to squeeze through. The only light was provided by three bare hanging bulbs and four video monitors, each mounted on a different wall. The monitors all played the same Woody Woodpecker cartoon. Doodlebug watched the dim primary colors play over the broad, flat faces of the men and women in the beds. They were strapped down; most had plastic tubing protruding from their arms, although whether the machines were injecting liquid nutrients or extracting blood, Doodlebug couldn’t tell. Their widely spaced, small eyes followed him as he walked past. A few smiled, revealing mouthfuls of teeth like broken shells on a dirty beach.

“This is only half of the herd,” Besthoff said. “In 1882, when we took over their care from the soon-to-be-disbanded Little Sisters of the Blessed Bayou, we started with only twenty-six. Since then, we’ve bred seven generations. They eat strictly balanced diets, to ensure that their blood is as healthful as possible. They are walked around the grounds every other evening. Due to their high fluid and nutrient intake, they can be blooded every two weeks. Every so often, we are able to train a few of the more high-functioning ones to provide basic sanitary care for their fellows.”

“Given the current situation with the young masters,” Straussman said solemnly, “perhaps it would be wise to accentuate our training efforts with the more clever of these creatures. If I may say so, I believe such a course of action would be greatly preferable to bringing in outside help.”

“That is so obvious as to be barely worth mentioning,” Besthoff snapped, irritation coloring his usually imperturbable voice. He clasped his hands behind his slender waist and took a lingering look at the hundred-and-twenty beds and their occupants. Pride and apprehension seemed to battle for control of his sharply handsome features. Pride won. “How ironic,” he said, “that the Vatican, when they shut down one of their faltering nunneries here in the hinterlands, should have provided our High Krewe with the greatest boon we ever received.” His smile faded, and he slowly shook his head. His next words were so low that Doodlebug barely heard them. “How they could even consider leaving this behind . . . I cannot understand it.”

Doodlebug wasn’t sure which they Besthoff referred to. He didn’t have long to ponder, however, because the grim-faced vampire motioned them forward again. “Come, Mr. Richelieu. This is not what I brought you to see.”

They reached the far end of the dormitory. Three doors were set within the blue plastered wall. Besthoff directed Straussman to unlock the far-right door. Doodlebug noticed that the key to this door was on a separate, smaller key ring that Straussman removed from a buttoned pocket inside his coat. Both Straussman and Besthoff ducked their heads upon entering the room. Doodlebug was able to walk through the doorway without ducking, although barely two inches separated his pulled-back hair from the beam above.

The space they entered was completely dark. The air smelled dusty and stale. Doodlebug heard the sound of a light fixture’s chain being pulled. A forty-watt bulb dimly illuminated what was originally a storage room, bare brick walls windowless and gloomy. Only now it was being used as a bedroom, or perhaps an infirmary.

Two young women slept within coffins placed on narrow iron beds identical to those in use outside. Or they appeared to sleep. Doodlebug walked closer to one of the women, a pale, pretty brunette whose mouth looked hard, even in slumber. Her breathing was so shallow and so slow that she seemed not to breathe at all. She was covered, from the neck down, with a light linen blanket. Doodlebug noticed that an intravenous-drip machine, the same type that stood next to many of the imbeciles outside, fed a dark red substance through a plastic tube that disappeared beneath the blanket. But that wasn’t all that disappeared beneath the blanket. Doodlebug’s eyes followed the graceful curves of her torso from her bust to her flat stomach. Below her pelvis, the blanket fell to the floor of the coffin. As if her body suddenly . . . ended.

Doodlebug felt Besthoff’s eyes on him. “Go ahead,” his host commanded. “Lift the blanket and look. You will not awaken her.”

Doodlebug held his breath as he lifted the blanket’s lower edge. The woman was dressed in a plain white nightgown. Its unoccupied lower reaches lay flat on the thin layer of earth at the bottom of the coffin, like an airless balloon. She had no legs.

Doodlebug let the blanket fall and stepped back from the coffin. “How—how long has she been like this?”

“Little less than a week,” Besthoff said. Doodlebug detected a note of weary sadness in his voice; of mourning and of anger. “Victoria was one of our finest dancers. So graceful; you should have seen her pirouetting through the gardens, making leaps that would shame a gazelle. Watching her dance was one of my most reliable pleasures. Unfortunately, the two dozen of us here within the compound were not audience enough for her. She insisted on seeking thrills and pleasures beyond our walls. And now she will dance no more.”

“Do you have any idea what happened to her?”

“She went outside,” Besthoff said. “Like so many of the young ones have been doing of late. It is impossible to stop them. The lure of that damnable city”—Doodlebug saw his host’s face darken like a thundercloud—“is too strong. Straussman took a call last Thursday. The anonymous caller instructed him to enter the woods outside the gates, that there was a ‘lost treasure’ waiting there. He went outside with two of the other servants. They found her, wrapped in a bed sheet. As you see her now.”

“Has she regained consciousness? Spoken to anyone?”

“No. She seems to be in a very deep coma. Extremely deep. Not even my powers of hypnotism—not even the combined powers of myself, Katz, and Krauss—have been up to the task of bringing her out of the mental cavern she has been forced to retreat within.”

Doodlebug took a second look at the blood-drip apparatus. “A mutilation of that magnitude”—he shivered, then blushed with embarrassment— “. . . she must have lost a tremendous volume of blood.”

“You would not have known it, sir,” Straussman interjected, “from her condition when we found her. Her wounds were sealed. Completely. The flesh at the bottom of her, ah, pelvis, it was without blemish or scar. As though she had been born . . . legless.”

“Show him Alexandra,” Besthoff commanded.

Straussman approached the open coffin of the other woman, who was elegantly tall, with long platinum tresses and striking Eurasian features. She made Doodlebug think of a Siberian wolf, white-furred and gorgeously savage. Straussman pulled back her blanket. Unlike the first woman’s mutilation, Alexandra’s was not hidden by her nightgown. Lacy spaghetti straps rested on pale, beautifully formed shoulders that simply ended. The slight protrusions of her shoulder blades sloped in a graceful, unbroken curve into the concavities of her armpits, and then into the swellings of her breasts and the subtle undulations of her rib cage.

“Two nights ago,” Besthoff said, “we received a second call. This time, Krauss and I accompanied Straussman outside the walls. Alexandra was left for us farther away from the compound than Victoria had been. The assailant must have suspected that we would line our walls and the surrounding woods with surveillance cameras, as we indeed had done. She was left for us in the Metairie Cemetery, to the north of Metairie Road. We found her next to the crypt of a Confederate captain of artillery.”

“She was left the same as Victoria?”

“Yes. Wrapped in a bed sheet, unstained with blood or any sign of violence. Trapped in the deepest of comas.”

Straussman carefully rearranged the blanket beneath Alexandra’s chin. With the blanket covering her shallowly breathing form, she looked virtually normal; certainly more so than Victoria. Doodlebug was not as surprised by the absence of fleshy derangement where the women’s limbs were missing as he imagined Besthoff and company had been. His thirteen years with the monks in Tibet had taught him much about the wonders of vampiric physiognomy, the astounding supernatural plasticity that was not at all limited to the traditional European transformational varieties of bat, wolf, and mist.

“Who knows about this?” Doodlebug asked.

“Straussman and two of the other servants,” Besthoff said. “And Katz, Krauss, and myself.”

“The police haven’t become involved?”

“Of course not,” Besthoff snapped. “Who here would have called them?”

“No one, I’m sure,” Doodlebug said; Besthoff’s fierce gaze had him feeling defensive. “But it’s possible that an outsider could’ve seen you removing Alexandra from Metairie Cemetery and alerted the authorities.”

“We were exceptionally discreet.”

“I see,” Doodlebug said. “So what are your plans for investigating . . .” The question died on his tongue. He was their plan. Determining who was behind this violence and, presumably, ensuring that it wasn’t repeated—this was the reason he’d been summoned from California. The High Krewe couldn’t dirty their hands with such matters. More likely, they simply weren’t up to the job—they’d spent so many decades living in splendid isolation behind these high walls, they’d lost the ability to deal effectively with the outside world.

He glanced back at Victoria’s legless figure. Detective work certainly wasn’t his strong suit. But if he could hunt down the culprit, deliver him to justice (Doodlebug did not want to imagine what the High Krewe would consider “justice” under these circumstances), and restore these young women, he might be able to avoid having his Institute overrun by amoral, spoiled refugees. He turned back to Besthoff, who was still waiting for him to finish his earlier question. “I take it that you’d like me to investigate these crimes,” Doodlebug said.

“Actually, no.”

“No?”

Besthoff smiled slightly. “No. You are too valuable to us. Investigating this villain’s crimes is likely to be a hazardous business. There is also the factor of your unfamiliarity with the city. Although you grew up here, you have been mostly absent from New Orleans for the past fifty years. We need someone who knows this filthy, misbegotten city intimately. Someone who has trafficked with the lower classes of both races, who frequents the despicable taverns and brothels, who knows the trash-strewn alleyways because he regularly dines in them. Someone powerful, in his way. But expendable.”

“Who?” Doodlebug asked in a small voice. His spirits sank. He already knew the answer.

“We need Duchon. Jules Duchon.” Besthoff’s iron gaze belied the polite cordiality of his smile. “He has not been h

When he was ten feet from the gate, something scurried near his feet. He saw something run into the underbrush, a mouse or squirrel or maybe a small rat. Doodlebug smiled a wistful smile. The tiny mammal had made him think of Jules. As he had innumerable times during the past eight months, Doodlebug wondered how the Fates had been treating his vanished friend. He hoped with all his heart that Jules had found happiness.

The iron gates towered before him like the entrance to one of Dante’s inner circles of Hell. Doodlebug pressed the cold steel button that protruded from the marble gatepost. A disguised panel slid open, revealing a video screen. A dignified, somewhat haughty face appeared; a computer-generated image, Doodlebug realized, since the butler was himself a vampire and could not be photographed. Above him, at the top of the entrance archway, a small camera tracked his movements. All it would reveal to the viewer on the other end was a knee-length black dress, pale ivory lace hosiery, sensible black pumps, earrings, and lipstick of a modest shade of red.

“I’m Rory Richelieu,” Doodlebug said. It felt odd to call himself by his birth name; normally he went by Debbie, and whenever he’d returned to New Orleans to see Jules or Maureen, he’d always slipped back into his childhood nickname, Doodlebug. “I flew out from California. Georges Besthoff asked me to come.” Asked was too pale a word; demanded was more like it.

The face on screen appeared to be examining a list. “Yes. Mr. Richelieu. I’ve been told to expect you. Master Besthoff is awaiting you in the library.”

The massive iron gate swung open as smoothly and silently as silk on silk. The scent of pomegranates reached him on a cool breeze. Blood apples. High above, at the center of a cloud-dimpled sky, a half-moon illuminated stately groves and manicured gardens, all of which would appear quite at home surrounding the ancient fortress-estates of Moravia or Romania. Doodlebug had not set foot within the gates of the compound of the High Krewe of Vlad Tepes in decades. Not since 1968, just after he’d completed his thirteen years of study in Tibet, when he’d been planning to leave New Orleans for California to establish his Institute of Higher Alpha-Consciousness.

As grand and beautiful as this walled assemblage of mansions and gardens was, he’d never felt any fondness for this place. Most of the vampires here were far older than he was, immigrants from Eastern Europe, one of the cultural hearts of world vampirism, and had amassed their impressive fortunes over hundreds of years. The wisdom of their collective centuries had not brought them enlightenment, as it had to Doodlebug’s Tibetan monk teachers; instead, it had taught them to pursue their own narrow interests with scientific precision. As a fledgling vampire, he’d considered himself a catfish among tiger sharks in his dealings with the masters of this place. He’d always suspected they’d granted their support to his California project only because they’d judged him to be an interesting, potentially useful freak.

Doodlebug hadn’t heard a peep from the High Krewe’s masters in a quarter century. What did they want with him now? Besthoff certainly hadn’t ordered him to fly across the continent for a social call. He had been infuriatingly evasive in his communiqués, as he always was. But he’d left no doubt that he was willing to pound the stake through Doodlebug’s most precious aspirations if Doodlebug failed to comply.

Doodlebug walked briskly past fountains illuminated with beams of green, red, and white, the colors of the old Hungarian monarchy. He sensed an unfamiliar dampness under his smooth arms, despite the chill in the air; he was thankful that he’d chosen to wear black. Apprehensive as he was about the nature of his mysterious task, he was eager to get the undoubtedly sordid business over with as quickly as possible.

He climbed the broad marble stairs that led to the compound’s central building, an Italianate mansion easily twice as large as the grandest home on St. Charles Avenue. Twin twelve-foot-high doors opened soundlessly before he could knock.

“Mr. Richelieu. Welcome. It is a pleasure to see you again after all these years.”

The sentiment sounded as sincere as a local politician’s promises to fix the potholes. Doodlebug stared up at the long, sallow face of Straussman the butler. He was even haughtier and more austere than his computer-generated image; Doodlebug, an avid fan of the films of the forties, thought Straussman made Erich von Stroheim look like Lou Costello. Nevertheless, he smiled and answered Straussman’s stiff bow with a polite curtsy.

“Thank you, Straussman. The years have been good to you.”

“You are too kind, sir.”

Straussman closed the doors, polished oak eight-inches thick, with little discernible effort. “Please allow me to escort you to the library.”

They left the entrance foyer and entered a tall, wide hallway decorated with tapestries large enough to cloak elephants. Doodlebug remembered these tapestries well. Each depicted a victory of King Vlad Tepes over the marauding Turks, who were portrayed as beasts with barely human features. The largest of the tapestries showed Vlad Tepes holding court in front of a panorama of severed Turkish heads impaled on tall wooden spikes.

Just before they reached the library, Straussman paused and turned back toward Doodlebug. “We have been experiencing unsettled times within our household,” he said in a low voice, almost a whisper. Doodlebug detected a slight change in his normally imperturbable face, a hint of what might almost pass for concern. “The young masters . . .” His voice trailed off. It was fascinating and unsettling to watch Straussman struggle for words. “I do hope, sir, that you will be able to assist Master Besthoff in bringing certain matters to a satisfactory close. Bringing certain . . . foul parties to the justice they richly deserve.”

Then he turned away again, and Doodlebug watched him straighten his neck and torso to their habitual lacquered stiffness before he opened the doors of the library. “Master Besthoff,” he said, “if you would kindly forgive the intrusion, I have the pleasure of presenting Mr. Rory Richelieu.”

“Thank you, Straussman,” a deep, fine-grained voice, tinged slightly with a Rumanian accent, answered. “You may show him in.”

Doodlebug hurriedly smoothed the wrinkles from his dress and entered the library. Of all the compound’s hundreds of rooms, this was the one that had always fascinated him the most. He was greeted by a seductive perfume of polished teak and aged paper. His mouth fell open as he craned his neck to take in the thousands of volumes, most of them more than a century old. The inhabitants of this compound had millions of empty hours to fill, particularly since they had “advanced beyond the primitive hunting and gathering stage,” to use Besthoff’s memorable phrase. What better place to spend some of those millions of hours than this cathedral of literature, open all night long?

However, apart from Doodlebug and Straussman, who hovered near the entrance in readiness for additional tasks, the library held only one occupant. Georges Besthoff sat in a high-backed, gilded Queen Anne chair beside a tall Tiffany lamp and a coffee table decorated with the wings and clawed feet of a gryphon. He was as tall as Straussman, but far broader through the chest. Untold centuries in age, he didn’t appear any older than his midforties, with only an occasional strand of silver flashing within the midnight blackness of his immaculately groomed hair. His eyes were coals that had been compressed by unnatural gravity into onyx diamonds, glowering with negative light.

Doodlebug frowned slightly as he remembered how Besthoff and the others had built their fortunes in Europe. Among the oldest of that region’s vampires, they had gradually seduced many of the neighboring noble families into the blood-sucking fraternity, convincing them to leave one aristocracy for another; then they had taken advantage of the nouveau vampires’ junior status to appropriate portions of their holdings. If it hadn’t been for the antiroyal revolutions of 1848, Besthoff, Katz, and Krauss would never have left the enriching embrace of their ancestral lands for New Orleans.

Besthoff’s smile was well rehearsed, the practiced smile of a diplomat from the age of dynastic empires. “Mr. Richelieu,” he said, gesturing for him to sit in the chair on the far side of the gryphon table, “I believe the last time you visited us, that Texan excrescence, Lyndon Johnson, was still in the White House. It has been too long.” He looked Doodlebug over with a coolly appraising glance, his eyes lingering on the swellings of his guest’s hips and bustline. “I see that you have honed your talents considerably since the last time we met. Were I ignorant of your natural sex, I would be most aroused by your display of lush, young femininity.”

Doodlebug felt hot blood rush into his face. It wasn’t a sensation he felt often. He’d grown used to being around people who accepted him as a woman, who didn’t know differently. Now, in the presence of this man who knew him to be a fellow man, who could take away his independence with the snap of his fingers, Doodlebug experienced for the first time the sense of relative powerlessness that so many women suffered. “Maintaining continual control over my form,” he said too quickly, “is a useful exercise in spiritual discipline.”

“Yes,” Besthoff said, smiling. He interlocked his long fingers, flex- ing the powerful muscles of his hands. “That must be so, I am sure.” He glanced toward Straussman and signaled with a slight tilt of his head that the butler should attend to him. “But I forget my obligations as host. You are famished after your long air journey. All those distressing changes in air pressure. Would you prefer blood or a glass of wine?”

Doodlebug took a moment to consider this. With men such as Besthoff, there were no gifts; accepting even the smallest of boons meant allowing the cords of obligation to be pulled ever tighter. There was good reason he’d air-shipped his coffin and a week’s supply of blood to a New Orleans bed-and-breakfast inn where he’d stayed before, rather than accept Besthoff’s offer of lodging in the mansion. Truthfully, a long drink of the life-giving ichor would restore his strength and possibly settle his nerves. But he couldn’t bury the thought that the less obligated he was to the High Krewe, the better off he’d be.

“Well?” Besthoff said, raising an eyebrow, a hint of amusement in his dark eyes. “What will you have, Mr. Richelieu?”

“A pot of herbal tea would be lovely,” Doodlebug said. He glanced up at Straussman’s unreadable face. “Could you fix me some chamomile?”

“I will check the pantry, sir,” Straussman said.

“Very well,” Besthoff said. He frowned and waved Straussman away. “Bring me my usual midevening cocktail.” He turned back to his guest. “How fares your Institute?” he asked, a polite smile reaffixed upon his predatory face.

To Doodlebug’s ears, his host’s expression of interest was wrapped around a core of cold condescension. It wasn’t at all surprising that, after Doodlebug declined his host’s offer of blood, Besthoff would focus on the vulnerability that granted him the greatest degree of leverage over his guest. Doodlebug closed his eyes for a second and attempted to picture a perfectly calm sea. “It fares very well, thank you,” he said, his eyes open again. “I currently have forty-two students. Twenty-three reside on my campus. The others commute from surrounding towns.”

“So the passion for Eastern mysticism has not subsided in your part of the country?”

“Apparently not, no.”

“Your students,” Besthoff continued, “they still make their monthly ‘donations’ of blood during their periods of study?”

“Every six weeks, yes. It’s part of their cycle of cleansing and purification. All of my students are strict vegetarians. The blood-letting complements their regimens of fasting and ascetic yoga.”

“Very clever,” Besthoff said, a hint of genuine admiration in his voice. “I always expected that our investment would return interesting dividends. Have any of your students expressed any opinions regarding this regimen of ‘blood-letting,’ as you call it? Do you think they suspect vampirism might be the motivating factor?”

“California is different from the rest of the country,” Doodlebug said, shifting in his seat. He pulled the edges of his dress well below his knees, then chided himself for doing so. “A combination of widespread Wiccanism and Hollywood liberalism means that blood-drinking is not as stigmatized as it would be here. All that aside, my students accept me as what I present myself to be—a spiritual mentor and a fellow learner. I’ve never overheard any whisperings of vampirism. Such suspicion and distrust are the opposite of all that my students seek to achieve.”

“Yes. Of course.” Straussman returned with a silver tray. A white china teapot, embossed with twirling roses, emitted a strong aroma of Earl Grey through its spout. Oh, well, Doodlebug thought. Close enough. Straussman set the tray down on the gryphon table and served Besthoff his cocktail, which, Doodlebug guessed from its scent, was a mixture of sherry and blood.

Besthoff took a sip of his cocktail and eyed Doodlebug evenly over the rim of the expansive goblet. “Would you expand the Institute, if you were able? Do you feel you could attract a larger number of students?”

“It’s . . . possible,” Doodlebug said, measuring his words carefully. What was Besthoff driving at? “Although I couldn’t handle many more students myself. If I allowed more students in, I’d need to train additional instructors. Additional instructors would require expanding my physical plant.”

“That could potentially be arranged.” Doodlebug felt Besthoff’s eyes drilling into his. The tall man set down his goblet and leaned closer. “Our household has been experiencing some disquietude of late. Some of the younger members have begun to . . . chafe within what they feel to be unreasonable restrictions on their liberties. You were once the child protégé of that Duchon person, were you not?”

The mention of Jules’s name brought a flood of memories. Only eight months had passed since he’d taught his friend and blood-father the skills he needed to overcome the deadly challenge posed by a group of new, young black vampires.

The distaste in Besthoff’s voice when he uttered Jules’s name was unmistakable. “Yes,” Doodlebug said. “Jules turned me in 1943, during the war. He wanted a sidekick to help him protect New Orleans’s munitions plants from Nazi saboteurs.”

“But you did not stay with him long after the war was over, did you? You began your spiritual quest, which eventually led you to Tibet. Correct?”

“That’s true. But I might have stayed longer with Jules in New Orleans if he hadn’t been so uncomfortable with my, ah, proclivities.” Doodlebug stared at the crimson-painted nails that adorned his slender fingers, now interlaced tightly on his lap.

“In any case, I expect you have some understanding of the rebellious impulses that often accompany youth. A need to break away from the often sensible lifestyle of one’s elders, to establish one’s own identity and autonomy.”

“That’s a common preoccupation of youth in all societies. Even vampiric ones. It’s not unhealthy.”

“In many cases, perhaps.” Besthoff took another sip from his goblet. He let it linger in his mouth before swallowing. “But in the case of my little society, my High Krewe, youthful rebellion and indiscretion have led to outcomes most unhealthy.” The dark red tip of his tongue brushed his lower lip. “Tragic outcomes. Events which I deeply regret, and which I cannot allow to go unaddressed.”

Doodlebug waited for him to continue. He picked up the cup of tea Straussman had poured for him. The liquid burned the roof of his mouth.

“I will speak more of this in a moment,” Besthoff said after many long seconds. “The restless energies of youth are difficult to contain, even in the face of tragedy. I may need to find a safe haven for several of our youngsters away from this compound, in a place where they can feel they have broken away from the nest, and so will not be tempted into dangerous pursuits. I believe your Institute would be an ideal place for them to ‘find themselves’ without endangering themselves.”

Doodlebug’s face tightened as the reason for his summons to the compound of the High Krewe of Vlad Tepes became clear. The Krewe had never interfered in his running of the Institute before. They’d never had reason to. Until now. But now, from the sound of things, he was expected to take in a bunch of spoiled, aristocratic vampires, most of whom probably had zero interests outside of sex, leisure, and a good meal, and try to guide them on a path toward enlightenment. “You want me to take them on as students? How would I keep them fed? Even with strict rationing, the blood donations provided by my current students would barely sustain me and one other vampire.”

“I don’t expect you to take them on as students,” Besthoff said. “I expect you to take them on as instructors. Each will need to be provided with a complement of students adequate to supply him with a steady diet. The High Krewe will provide financial support for the construc- tion of expanded facilities, advertising to attract additional students, et cetera.”

Doodlebug’s alabaster skin turned a sicklier shade of white. His dream. The great spiritual project that gave his undead existence meaning. They wanted to pervert it, to take it in their filthy hands and reshape it in their own cruel, selfish image. He’d known, of course, when he’d first acquired the monumental loan from the High Krewe to buy his twenty-five acres of oceanfront property and construct his austere campus, that a quid pro quo was likely. But he’d spent decades avoiding that possibility, pushing it into the dustiest corners of his mind.

“You ask . . . very much of me,” he managed to say at last. “This is the reason you demanded I come here? To recruit your youngsters?”

Besthoff smiled tightly. “Not exactly, no. That is more of a long-term goal. I recognize that such arrangements as I have spoken of will take time. You will need to make plans. The more restless youngsters will need to be convinced that a move to Northern California is indeed what they want.”

Besthoff stood, rising to his imposing full height of six feet and five inches. “No, Mr. Richelieu, the reason I had you come is far more pressing. Follow me, please. What I am about to show you will make my needs and your responsibility abundantly clear.”

He walked to the library’s entrance. Doodlebug set his teacup down (caffeine was the last thing he needed at this point, anyway) and followed. Besthoff motioned for Straussman to accompany them. The butler opened a set of tall French doors that led to a courtyard of formal gardens and hedges trimmed as exactingly as a nobleman’s mustache.

At the far end of the gardens, beyond the ponderous wings of the main mansion, sat a separate building much more plain and simple than the one Doodlebug had just left. Not that it was not ornate; it reminded Doodlebug of the redbrick Catholic schoolhouse he’d attended before he’d met Jules. They climbed three steps to a broad porch lined with white wooden posts. Straussman removed a large ring of keys from his coat pocket and unlocked the door.

They stepped inside the entrance foyer, and Straussman locked the door behind them. Doodlebug crinkled his elfin nose. The odor he smelled wasn’t repulsive, at least not overwhelmingly so. He remembered the odor from years ago, when he’d been a small child and a broken arm had landed him within the crowded wards of Charity Hospital for a week. It was the collective scent of dozens of people who spent their days and nights confined to bed, who bathed infrequently and changed their garments less often than they bathed and who relieved themselves in bed pans.

“You may remember our farm,” Besthoff said. “I can’t recall whether I granted you a tour the last time you visited.”

“I’ve never been inside here, no,” Doodlebug said.

“But you’re aware of the economic underpinnings of our compound, of course? Our blood-cows?”

Blood-cows. Doodlebug frowned slightly. It didn’t seem right to refer to human beings that way. Not even human beings of the sort who lived here. “So this is where the, uh, mentally handicapped individuals are cared for?”

“Yes.” He gestured for Straussman to turn on the lights in the next room. “Please forgive the slight stench. Over the past year, it has become harder and harder to get our young people to fulfill their obligations here. We threaten them with cutting back on their blood rations if they miss shifts. But one can only take such threats so far without it becoming counterproductive. And Straussman and the other household staff are limited in how much time they can take from their primary duties to tidy up here.”

They walked into the main room. The building was much deeper than it had looked from the outside, Doodlebug realized. This dormitory contained four rows of thirty beds each; the beds were about eighteen inches apart, and the aisles between rows allowed two people abreast to squeeze through. The only light was provided by three bare hanging bulbs and four video monitors, each mounted on a different wall. The monitors all played the same Woody Woodpecker cartoon. Doodlebug watched the dim primary colors play over the broad, flat faces of the men and women in the beds. They were strapped down; most had plastic tubing protruding from their arms, although whether the machines were injecting liquid nutrients or extracting blood, Doodlebug couldn’t tell. Their widely spaced, small eyes followed him as he walked past. A few smiled, revealing mouthfuls of teeth like broken shells on a dirty beach.

“This is only half of the herd,” Besthoff said. “In 1882, when we took over their care from the soon-to-be-disbanded Little Sisters of the Blessed Bayou, we started with only twenty-six. Since then, we’ve bred seven generations. They eat strictly balanced diets, to ensure that their blood is as healthful as possible. They are walked around the grounds every other evening. Due to their high fluid and nutrient intake, they can be blooded every two weeks. Every so often, we are able to train a few of the more high-functioning ones to provide basic sanitary care for their fellows.”

“Given the current situation with the young masters,” Straussman said solemnly, “perhaps it would be wise to accentuate our training efforts with the more clever of these creatures. If I may say so, I believe such a course of action would be greatly preferable to bringing in outside help.”

“That is so obvious as to be barely worth mentioning,” Besthoff snapped, irritation coloring his usually imperturbable voice. He clasped his hands behind his slender waist and took a lingering look at the hundred-and-twenty beds and their occupants. Pride and apprehension seemed to battle for control of his sharply handsome features. Pride won. “How ironic,” he said, “that the Vatican, when they shut down one of their faltering nunneries here in the hinterlands, should have provided our High Krewe with the greatest boon we ever received.” His smile faded, and he slowly shook his head. His next words were so low that Doodlebug barely heard them. “How they could even consider leaving this behind . . . I cannot understand it.”

Doodlebug wasn’t sure which they Besthoff referred to. He didn’t have long to ponder, however, because the grim-faced vampire motioned them forward again. “Come, Mr. Richelieu. This is not what I brought you to see.”

They reached the far end of the dormitory. Three doors were set within the blue plastered wall. Besthoff directed Straussman to unlock the far-right door. Doodlebug noticed that the key to this door was on a separate, smaller key ring that Straussman removed from a buttoned pocket inside his coat. Both Straussman and Besthoff ducked their heads upon entering the room. Doodlebug was able to walk through the doorway without ducking, although barely two inches separated his pulled-back hair from the beam above.

The space they entered was completely dark. The air smelled dusty and stale. Doodlebug heard the sound of a light fixture’s chain being pulled. A forty-watt bulb dimly illuminated what was originally a storage room, bare brick walls windowless and gloomy. Only now it was being used as a bedroom, or perhaps an infirmary.

Two young women slept within coffins placed on narrow iron beds identical to those in use outside. Or they appeared to sleep. Doodlebug walked closer to one of the women, a pale, pretty brunette whose mouth looked hard, even in slumber. Her breathing was so shallow and so slow that she seemed not to breathe at all. She was covered, from the neck down, with a light linen blanket. Doodlebug noticed that an intravenous-drip machine, the same type that stood next to many of the imbeciles outside, fed a dark red substance through a plastic tube that disappeared beneath the blanket. But that wasn’t all that disappeared beneath the blanket. Doodlebug’s eyes followed the graceful curves of her torso from her bust to her flat stomach. Below her pelvis, the blanket fell to the floor of the coffin. As if her body suddenly . . . ended.

Doodlebug felt Besthoff’s eyes on him. “Go ahead,” his host commanded. “Lift the blanket and look. You will not awaken her.”

Doodlebug held his breath as he lifted the blanket’s lower edge. The woman was dressed in a plain white nightgown. Its unoccupied lower reaches lay flat on the thin layer of earth at the bottom of the coffin, like an airless balloon. She had no legs.

Doodlebug let the blanket fall and stepped back from the coffin. “How—how long has she been like this?”

“Little less than a week,” Besthoff said. Doodlebug detected a note of weary sadness in his voice; of mourning and of anger. “Victoria was one of our finest dancers. So graceful; you should have seen her pirouetting through the gardens, making leaps that would shame a gazelle. Watching her dance was one of my most reliable pleasures. Unfortunately, the two dozen of us here within the compound were not audience enough for her. She insisted on seeking thrills and pleasures beyond our walls. And now she will dance no more.”

“Do you have any idea what happened to her?”

“She went outside,” Besthoff said. “Like so many of the young ones have been doing of late. It is impossible to stop them. The lure of that damnable city”—Doodlebug saw his host’s face darken like a thundercloud—“is too strong. Straussman took a call last Thursday. The anonymous caller instructed him to enter the woods outside the gates, that there was a ‘lost treasure’ waiting there. He went outside with two of the other servants. They found her, wrapped in a bed sheet. As you see her now.”

“Has she regained consciousness? Spoken to anyone?”

“No. She seems to be in a very deep coma. Extremely deep. Not even my powers of hypnotism—not even the combined powers of myself, Katz, and Krauss—have been up to the task of bringing her out of the mental cavern she has been forced to retreat within.”

Doodlebug took a second look at the blood-drip apparatus. “A mutilation of that magnitude”—he shivered, then blushed with embarrassment— “. . . she must have lost a tremendous volume of blood.”

“You would not have known it, sir,” Straussman interjected, “from her condition when we found her. Her wounds were sealed. Completely. The flesh at the bottom of her, ah, pelvis, it was without blemish or scar. As though she had been born . . . legless.”

“Show him Alexandra,” Besthoff commanded.

Straussman approached the open coffin of the other woman, who was elegantly tall, with long platinum tresses and striking Eurasian features. She made Doodlebug think of a Siberian wolf, white-furred and gorgeously savage. Straussman pulled back her blanket. Unlike the first woman’s mutilation, Alexandra’s was not hidden by her nightgown. Lacy spaghetti straps rested on pale, beautifully formed shoulders that simply ended. The slight protrusions of her shoulder blades sloped in a graceful, unbroken curve into the concavities of her armpits, and then into the swellings of her breasts and the subtle undulations of her rib cage.

“Two nights ago,” Besthoff said, “we received a second call. This time, Krauss and I accompanied Straussman outside the walls. Alexandra was left for us farther away from the compound than Victoria had been. The assailant must have suspected that we would line our walls and the surrounding woods with surveillance cameras, as we indeed had done. She was left for us in the Metairie Cemetery, to the north of Metairie Road. We found her next to the crypt of a Confederate captain of artillery.”

“She was left the same as Victoria?”

“Yes. Wrapped in a bed sheet, unstained with blood or any sign of violence. Trapped in the deepest of comas.”

Straussman carefully rearranged the blanket beneath Alexandra’s chin. With the blanket covering her shallowly breathing form, she looked virtually normal; certainly more so than Victoria. Doodlebug was not as surprised by the absence of fleshy derangement where the women’s limbs were missing as he imagined Besthoff and company had been. His thirteen years with the monks in Tibet had taught him much about the wonders of vampiric physiognomy, the astounding supernatural plasticity that was not at all limited to the traditional European transformational varieties of bat, wolf, and mist.

“Who knows about this?” Doodlebug asked.

“Straussman and two of the other servants,” Besthoff said. “And Katz, Krauss, and myself.”

“The police haven’t become involved?”

“Of course not,” Besthoff snapped. “Who here would have called them?”

“No one, I’m sure,” Doodlebug said; Besthoff’s fierce gaze had him feeling defensive. “But it’s possible that an outsider could’ve seen you removing Alexandra from Metairie Cemetery and alerted the authorities.”

“We were exceptionally discreet.”

“I see,” Doodlebug said. “So what are your plans for investigating . . .” The question died on his tongue. He was their plan. Determining who was behind this violence and, presumably, ensuring that it wasn’t repeated—this was the reason he’d been summoned from California. The High Krewe couldn’t dirty their hands with such matters. More likely, they simply weren’t up to the job—they’d spent so many decades living in splendid isolation behind these high walls, they’d lost the ability to deal effectively with the outside world.

He glanced back at Victoria’s legless figure. Detective work certainly wasn’t his strong suit. But if he could hunt down the culprit, deliver him to justice (Doodlebug did not want to imagine what the High Krewe would consider “justice” under these circumstances), and restore these young women, he might be able to avoid having his Institute overrun by amoral, spoiled refugees. He turned back to Besthoff, who was still waiting for him to finish his earlier question. “I take it that you’d like me to investigate these crimes,” Doodlebug said.

“Actually, no.”

“No?”

Besthoff smiled slightly. “No. You are too valuable to us. Investigating this villain’s crimes is likely to be a hazardous business. There is also the factor of your unfamiliarity with the city. Although you grew up here, you have been mostly absent from New Orleans for the past fifty years. We need someone who knows this filthy, misbegotten city intimately. Someone who has trafficked with the lower classes of both races, who frequents the despicable taverns and brothels, who knows the trash-strewn alleyways because he regularly dines in them. Someone powerful, in his way. But expendable.”

“Who?” Doodlebug asked in a small voice. His spirits sank. He already knew the answer.

“We need Duchon. Jules Duchon.” Besthoff’s iron gaze belied the polite cordiality of his smile. “He has not been h

Descriere

In the hilarious follow-up to Fox's debut novel, "Fat White Vampire Blues," Jules Duchon is back to investigate the mysterious serial killings of vampires in New Orleans.

Notă biografică

Andrew Fox