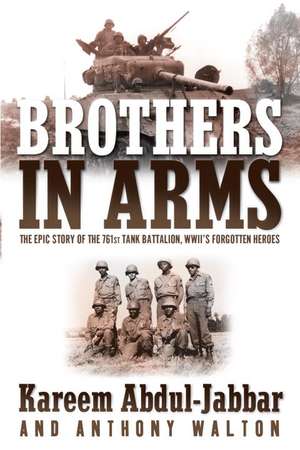

Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion, WWII's Forgotten Heroes

Autor Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Anthony Waltonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2005

Preț: 115.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.04€ • 23.07$ • 18.35£

22.04€ • 23.07$ • 18.35£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767909136

ISBN-10: 0767909135

Pagini: 330

Dimensiuni: 141 x 208 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767909135

Pagini: 330

Dimensiuni: 141 x 208 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Trade Pbk.

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

“A carefully researched and engrossing account that paints the individual dramas of the tankmen against the backdrop of the war . . . A fine tribute to these unsung heroes and a valuable addition to the literature on African American service in World War II.” —Washington Post Book World

More than a combat story or a segregated version of Stephen Ambrose's Band of Brothers. It's also the story of how black soldiers had to fight (literally and figuratively) for the right to fight the Germans.” —USA Today

“A wholly different perspective on the ‘greatest generation.’” —People (Critic's Choice)

“A brilliant and moving narrative that through its imagery helps the reader appreciate the hardness of battle.” —Charlotte Observer

“A slam dunk . . . Well written, well researched and an excellent read . . . Abdul-Jabbar does an incredible job of weaving [the personal stories] into the context of the war as it unfolded.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“A touching profile of men who fought overt and subtle racism for the chance to prove their mettle, and a poignant reminder of the unreasonable prejudices of that era that almost kept them on the sidelines.” —Sacramento Bee

“An inspirational, moving account of courage and comradeship on the part of exceptional men.” —Military History

“Not only an exciting, informative military history for the general reader but also a revealing and moving record of racism in America’s past.” —Houston Chronicle

More than a combat story or a segregated version of Stephen Ambrose's Band of Brothers. It's also the story of how black soldiers had to fight (literally and figuratively) for the right to fight the Germans.” —USA Today

“A wholly different perspective on the ‘greatest generation.’” —People (Critic's Choice)

“A brilliant and moving narrative that through its imagery helps the reader appreciate the hardness of battle.” —Charlotte Observer

“A slam dunk . . . Well written, well researched and an excellent read . . . Abdul-Jabbar does an incredible job of weaving [the personal stories] into the context of the war as it unfolded.” —Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“A touching profile of men who fought overt and subtle racism for the chance to prove their mettle, and a poignant reminder of the unreasonable prejudices of that era that almost kept them on the sidelines.” —Sacramento Bee

“An inspirational, moving account of courage and comradeship on the part of exceptional men.” —Military History

“Not only an exciting, informative military history for the general reader but also a revealing and moving record of racism in America’s past.” —Houston Chronicle

Notă biografică

KAREEM ABDUL-JABBAR, six-time NBA Most Valuable Player, is the author of the New York Times bestseller Giant Steps, as well as Kareem and A Season on the Reservation. ANTHONY WALTON is the author of the critically acclaimed memoir Mississippi, as well as the coauthor of Reverend Al Sharpton’s book Go and Tell the Pharoah.

Extras

1

VOLUNTEERS

The atmosphere of the whole country was

to get in the service and help.

I wanted to do my part.

--William McBurney

When seventeen-year-old Leonard Smith stepped off the United States Army troop train in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, in the fall of 1942, it was the first time he had been outside of New York State. For the last three days, he had been traveling with fourteen other recruits, headed to Camp Claiborne, seventeen miles southwest of Alexandria. There, they were to join a recently established armored unit. To Smith's surprise, the train stopped in an open field. The sergeants on the train threw the young soldiers' bags out and told them to get off. Smith and his companions, in full dress uniform and carrying their regulation duffel bags, waited for four hours in the empty field on the outskirts of the Kisatchie National Forest, watching the sun move across the sky. Finally, two of them set off on foot to find help.

Leonard Smith was one of the more than six hundred men who would come together at Camp Claiborne during the Second World War to form the 761st Tank Battalion. They would hail from over thirty states, from small towns and cities scattered throughout the country, from places as varied as Los Angeles, California, and Hotulka, Oklahoma; Springfield, Illinois, and Picayune, Mississippi; Billings, Montana, and Baltimore, Maryland. Most had volunteered. Some were the middle-class sons of doctors, undertakers, schoolteachers, and career military men; among the officers were a Yale student and a football star from UCLA who would later make his mark in American sports and American history. Many more were the sons of janitors, domestics, factory workers, and sharecroppers.

Their combat record in Europe during the war was noteworthy. They were to earn a Presidential Unit Citation for distinguished service, more than 250 Purple Hearts, 70 Bronze Stars, 11 Silver Stars, and a Congressional Medal of Honor in 183 straight days on the front lines of France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Austria. These accomplishments carried a significance, however, beyond the battlefield. The unit's official designation was "The 761st Tank Battalion (Colored)." As they waited in that hot Louisiana field, Leonard Smith and his fellow recruits were on their way to becoming part of the first African American unit in the history of the United States Army to fight in tanks.

In the fall of 1942, the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific seemed far from the backwater post of Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. They were as far from Leonard Smith's experience as Camp Claiborne had been before he boarded the train in New York City. Smith was born in Harlem Hospital on November 2, 1924; he was a sickly child at birth, weighing less than five pounds, with both colic and a heart murmur. His mother abandoned him shortly after he was born. Lulu Hasbruck, who worked for New York City taking in children with medical complications, cared for Smith during those early, precarious years. Other foster children regularly moved in and out of Hasbruck's home, but Smith and two girls, Thelma and Flora, remained. Smith would come to regard Lulu as his mother, though she never formally adopted him.

Despite his short, skinny frame and the heart murmur that kept him from playing school sports, Smith became an active, adventuresome child, regularly challenging other kids in his Brooklyn, and later Queens, neighborhood to footraces around the block. The neighborhood kids didn't seem to mind losing to him. There was something about him that adults and classmates immediately responded to, a combination of good-naturedness, irrepressibility, and naïveté that made him impossible to dislike.

He loved singing, and was good enough even at age eight to solo with the senior choir at local churches. But his obsession was airplanes. A favorite teacher rewarded students for exceptional performance by buying them a toy of their choice from the neighborhood five-and-dime. Smith hated arithmetic, but he worked hard to get high marks so that she would have to buy him a toy. He invariably picked out model planes, pictures of planes, and books about planes. Though he had never seen an airplane up close, there was something about the idea of planes and flying, the freedom of movement flying symbolized, that endlessly fired his high-spirited imagination.

Money was scarce. Clothes for foster children were provided by the city, a source of some discomfort for the children: People knew they were "home" children, wards of the city, because of the way they dressed. But the only thing Smith really missed was not having a father. When other kids in the neighborhood would talk about things they'd done with their fathers, he would make up stories about fishing trips and family outings. When asked why his father wasn't around, he would tell his friends his father was traveling on business. He made an imaginary father out of Mrs. Hasbruck's deceased husband, George, collecting countless details about him: Mrs. Hasbruck told him that George had smoked a pipe with Prince Albert tobacco, and Smith vowed that when he grew up he'd do the same. Mrs. Hasbruck's two brothers gave Smith spending money from time to time, but they rarely provided him with fatherly guidance. He had to learn everything for himself, and he often made mistakes.

One such mistake contributed to his decision to enlist in the Army. As a teenager, he had enrolled at Chelsea Vocational High School to study aviation mechanics. There he fell in with a group of older boys, budding delinquents who played hooky every Friday, shoplifting tools from local stores. It was typical of the guileless Smith that he continued going to class long after the boys he hung out with had stopped. It was also typical that while Smith's adventuresomeness led him to skirt the edges of disaster, his good-naturedness and good luck just as often kept him out. A neighborhood cop who knew and liked Smith pulled him aside, telling him that the boys he was running around with were going to wind up in prison one way or another. "Have you ever considered joining the Army?" he asked.

Smith had considered it--it was May 1942, and the United States had been at war for six months--but at seventeen, he had thought he was too young to enlist. American troops were already engaging in bloody combat in the Pacific, surrendering after a hopelessly one-sided struggle in the Philippines on May 6, but stalling the advance of the Japanese two days later in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Like millions of families across the country, the Hasbrucks listened to the radio every night for war updates. When he went to the local cinema, Smith avidly watched the early newsreels of combat. He knew exactly what he wanted to enlist as: a fighter pilot. He imagined himself streaking through the skies, on the lookout for Japanese Zeros, engaging in dogfights, dropping bombs on enemy aircraft carriers. In Smith's young mind, war was a kind of game. He had no concept of war's brutality, and he was eager to join the fight. At the policeman's suggestion, he went to the induction office on Whitehall Street in lower Manhattan carrying a permission form signed by his foster mother.

The doctor administering the Army physical failed to notice his slight heart murmur, and passed him. Smith told the recruiter who processed his application that he wanted to be a pilot. The sergeant told him that was not possible--the Army Air Corps did not accept blacks. Smith barely managed to swallow his disappointment. Citing his training in high school, he then said he wanted to be an aviation mechanic. Again, he was told that was not possible. The Army's rigid color line took Smith by surprise. Growing up in the New York City of the 1920s and '30s, he had encountered his share of discrimination: There were certain neighborhood pools where he was not permitted to go swimming, and certain stores where the entrance of anybody black was announced by ringing bells to rouse white clerks to extra vigilance. But despite such small daily indignities, it had somehow never occurred to him that the color of his skin would impact his future, his lifelong dream of working with planes.

He had scored high marks on the Army's IQ screening test. "Infantry you definitely don't want," the sergeant advised him. The next-best thing to the air force was armored, the sergeant said. "Armored?" Smith asked. The sergeant replied, "Tanks. They're starting a couple of colored tank battalions. How would you like that?" Smith had never seen a tank--in fact, he had no idea what a tank was. But he was game for anything. The sergeant told him that as a volunteer, "if that's what you want, that's where you're going to go."

William McBurney was as reserved and cautious as Leonard Smith was naive and adventuresome. Although the two men didn't know each other, McBurney took the subway to the induction office just days after Smith. His motives in doing so were mixed. Like Smith, he had watched the news updates of the war: A wave of patriotism had swept the country in the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and thousands of young men across the country enlisted every day. McBurney was eager to do his part for the war effort. But he also saw the Army as an escape.

McBurney was born in Harlem on May 21, 1924. His parents divorced when he was very young; his mother moved away to Florida, and he saw her only rarely after that. He was raised by his father and stepmother. When he was twelve years old, his younger brother died of scarlet fever. Though devastated by the loss, McBurney did what he had watched his father do all his life: bury the pain deep inside, and keep moving.

William had always been in awe of his father. A smart, determined, and ambitious man, his father had been born dirt poor around the turn of the century in Titusville, Florida. Seeing no prospects for advancement there, he had worked his way north to New York City as a railroad porter. At the outbreak of World War I, he had volunteered for the Army, serving in a quartermaster unit in Europe. When he returned to New York, still searching for a means of steady employment and advancement, he had worked his way through school to become a dental technician. But in the 1920s it was very difficult for blacks to find work in professional jobs. With a young wife and a growing family to support, he had no choice but to turn to manual labor, working on the docks and, later, with the advent of the Great Depression, for the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of the massive public works programs started by the federal government.

William McBurney was an intelligent, active boy. Despite his large size, he was not coordinated or good at sports: His one physical gift was a powerful right hook. Though he never went out of his way to seek out a fight, neither did he ever turn away from one. He got into the usual number of scrapes for a kid in Harlem in the 1930s--often chasing or being chased by Italian kids from adjacent neighborhoods--but he was also always at one remove from whatever he was doing, thinking several steps ahead. He had already noticed the kinds of trouble young black men often got into, especially with the police, and he intended to avoid it. With his air of watchfulness, his quiet, steady intelligence, and his physical courage, he stood out in his group of friends as the one you wanted watching your back.

Like Smith and countless other African Americans at that time, McBurney was tracked early in his school career toward shop class, regardless of his intelligence or academic success. Given the options available to him at New York Vocational High School, like Leonard Smith he chose to study aviation mechanics. A female cousin was taking flying lessons at Floyd Bennet Field, and watching that plane take off and sail away made McBurney dream of becoming a pilot. But as time went on, it was a dream he seemed to have less and less hope of attaining. After school and on Saturdays he worked at a paintbrush factory for twenty-five cents an hour, helping his family to weather the Depression. Many of his friends had taken similar menial jobs. As high school graduation approached, many more of his friends, with no real opportunities for advancement, were falling into gambling and petty theft. McBurney saw himself and his friends moving steadily toward dead-end lives.

Like many young men, he had romanticized his father's service in World War I--the more so because his taciturn father never talked about it. He saw the Army as a way of creating a new life for himself, and of realizing his secret dream of flying. When he told his father he wanted to join the Army Air Corps, he was surprised to find his father immediately dismissive. He didn't believe the Air Corps would accept an African American. This only made McBurney more determined. Three days after his eighteenth birthday, he took the train to the recruitment center on Whitehall Street.

His father's warning about the Air Corps turned out to be all too true--as Leonard Smith had already discovered, no blacks were allowed to join. To McBurney, it was a slap in the face. Nonetheless, he decided to enlist. Like Smith, he had scored high marks on the Army's intelligence test. Though he also had no idea what a tank was, he found himself, like Smith, steered by the recruiter into armored.

After passing his physical and being given his shots, McBurney was sent by train with several other fresh recruits to Camp Upton, a processing center surrounded by open potato fields in Suffolk County, Long Island. Thousands of Army recruits would move through the sprawling complex between 1941 and 1945. The recruits spent two weeks living in tents, where they were given close haircuts, uniforms, and basic gear; then they were moved into barracks. They performed a series of marching and close-order drills each day, learning the basics of military procedure and decorum, as well as carrying out KP duty and cleaning the grounds of the camp. Finding themselves with a great deal of free time on their hands, they held a series of boxing and softball tournaments as they waited endlessly, it seemed to McBurney, for their orders to come. During orientation, they had seen motivational documentaries chronicling the reasons the country was at war, highlighting the battles that had been fought to date, and firing them up against Germany and Japan. All were eager to get overseas and get started. They wanted in on the action.

The close friendships that would characterize the men in combat were already begining to form. William McBurney first met Leonard Smith at Camp Upton. Despite, or perhaps because of, their vast temperamental differences--Smith was the sort who leapt before looking, while McBurney was the one who held back; Smith's humor tended toward open-hearted playfulness, McBurney's toward irony and observation--the two became fast friends. Soon they became close to another recruit as well, soft-spoken Preston McNeil.

VOLUNTEERS

The atmosphere of the whole country was

to get in the service and help.

I wanted to do my part.

--William McBurney

When seventeen-year-old Leonard Smith stepped off the United States Army troop train in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, in the fall of 1942, it was the first time he had been outside of New York State. For the last three days, he had been traveling with fourteen other recruits, headed to Camp Claiborne, seventeen miles southwest of Alexandria. There, they were to join a recently established armored unit. To Smith's surprise, the train stopped in an open field. The sergeants on the train threw the young soldiers' bags out and told them to get off. Smith and his companions, in full dress uniform and carrying their regulation duffel bags, waited for four hours in the empty field on the outskirts of the Kisatchie National Forest, watching the sun move across the sky. Finally, two of them set off on foot to find help.

Leonard Smith was one of the more than six hundred men who would come together at Camp Claiborne during the Second World War to form the 761st Tank Battalion. They would hail from over thirty states, from small towns and cities scattered throughout the country, from places as varied as Los Angeles, California, and Hotulka, Oklahoma; Springfield, Illinois, and Picayune, Mississippi; Billings, Montana, and Baltimore, Maryland. Most had volunteered. Some were the middle-class sons of doctors, undertakers, schoolteachers, and career military men; among the officers were a Yale student and a football star from UCLA who would later make his mark in American sports and American history. Many more were the sons of janitors, domestics, factory workers, and sharecroppers.

Their combat record in Europe during the war was noteworthy. They were to earn a Presidential Unit Citation for distinguished service, more than 250 Purple Hearts, 70 Bronze Stars, 11 Silver Stars, and a Congressional Medal of Honor in 183 straight days on the front lines of France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Austria. These accomplishments carried a significance, however, beyond the battlefield. The unit's official designation was "The 761st Tank Battalion (Colored)." As they waited in that hot Louisiana field, Leonard Smith and his fellow recruits were on their way to becoming part of the first African American unit in the history of the United States Army to fight in tanks.

In the fall of 1942, the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific seemed far from the backwater post of Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. They were as far from Leonard Smith's experience as Camp Claiborne had been before he boarded the train in New York City. Smith was born in Harlem Hospital on November 2, 1924; he was a sickly child at birth, weighing less than five pounds, with both colic and a heart murmur. His mother abandoned him shortly after he was born. Lulu Hasbruck, who worked for New York City taking in children with medical complications, cared for Smith during those early, precarious years. Other foster children regularly moved in and out of Hasbruck's home, but Smith and two girls, Thelma and Flora, remained. Smith would come to regard Lulu as his mother, though she never formally adopted him.

Despite his short, skinny frame and the heart murmur that kept him from playing school sports, Smith became an active, adventuresome child, regularly challenging other kids in his Brooklyn, and later Queens, neighborhood to footraces around the block. The neighborhood kids didn't seem to mind losing to him. There was something about him that adults and classmates immediately responded to, a combination of good-naturedness, irrepressibility, and naïveté that made him impossible to dislike.

He loved singing, and was good enough even at age eight to solo with the senior choir at local churches. But his obsession was airplanes. A favorite teacher rewarded students for exceptional performance by buying them a toy of their choice from the neighborhood five-and-dime. Smith hated arithmetic, but he worked hard to get high marks so that she would have to buy him a toy. He invariably picked out model planes, pictures of planes, and books about planes. Though he had never seen an airplane up close, there was something about the idea of planes and flying, the freedom of movement flying symbolized, that endlessly fired his high-spirited imagination.

Money was scarce. Clothes for foster children were provided by the city, a source of some discomfort for the children: People knew they were "home" children, wards of the city, because of the way they dressed. But the only thing Smith really missed was not having a father. When other kids in the neighborhood would talk about things they'd done with their fathers, he would make up stories about fishing trips and family outings. When asked why his father wasn't around, he would tell his friends his father was traveling on business. He made an imaginary father out of Mrs. Hasbruck's deceased husband, George, collecting countless details about him: Mrs. Hasbruck told him that George had smoked a pipe with Prince Albert tobacco, and Smith vowed that when he grew up he'd do the same. Mrs. Hasbruck's two brothers gave Smith spending money from time to time, but they rarely provided him with fatherly guidance. He had to learn everything for himself, and he often made mistakes.

One such mistake contributed to his decision to enlist in the Army. As a teenager, he had enrolled at Chelsea Vocational High School to study aviation mechanics. There he fell in with a group of older boys, budding delinquents who played hooky every Friday, shoplifting tools from local stores. It was typical of the guileless Smith that he continued going to class long after the boys he hung out with had stopped. It was also typical that while Smith's adventuresomeness led him to skirt the edges of disaster, his good-naturedness and good luck just as often kept him out. A neighborhood cop who knew and liked Smith pulled him aside, telling him that the boys he was running around with were going to wind up in prison one way or another. "Have you ever considered joining the Army?" he asked.

Smith had considered it--it was May 1942, and the United States had been at war for six months--but at seventeen, he had thought he was too young to enlist. American troops were already engaging in bloody combat in the Pacific, surrendering after a hopelessly one-sided struggle in the Philippines on May 6, but stalling the advance of the Japanese two days later in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Like millions of families across the country, the Hasbrucks listened to the radio every night for war updates. When he went to the local cinema, Smith avidly watched the early newsreels of combat. He knew exactly what he wanted to enlist as: a fighter pilot. He imagined himself streaking through the skies, on the lookout for Japanese Zeros, engaging in dogfights, dropping bombs on enemy aircraft carriers. In Smith's young mind, war was a kind of game. He had no concept of war's brutality, and he was eager to join the fight. At the policeman's suggestion, he went to the induction office on Whitehall Street in lower Manhattan carrying a permission form signed by his foster mother.

The doctor administering the Army physical failed to notice his slight heart murmur, and passed him. Smith told the recruiter who processed his application that he wanted to be a pilot. The sergeant told him that was not possible--the Army Air Corps did not accept blacks. Smith barely managed to swallow his disappointment. Citing his training in high school, he then said he wanted to be an aviation mechanic. Again, he was told that was not possible. The Army's rigid color line took Smith by surprise. Growing up in the New York City of the 1920s and '30s, he had encountered his share of discrimination: There were certain neighborhood pools where he was not permitted to go swimming, and certain stores where the entrance of anybody black was announced by ringing bells to rouse white clerks to extra vigilance. But despite such small daily indignities, it had somehow never occurred to him that the color of his skin would impact his future, his lifelong dream of working with planes.

He had scored high marks on the Army's IQ screening test. "Infantry you definitely don't want," the sergeant advised him. The next-best thing to the air force was armored, the sergeant said. "Armored?" Smith asked. The sergeant replied, "Tanks. They're starting a couple of colored tank battalions. How would you like that?" Smith had never seen a tank--in fact, he had no idea what a tank was. But he was game for anything. The sergeant told him that as a volunteer, "if that's what you want, that's where you're going to go."

William McBurney was as reserved and cautious as Leonard Smith was naive and adventuresome. Although the two men didn't know each other, McBurney took the subway to the induction office just days after Smith. His motives in doing so were mixed. Like Smith, he had watched the news updates of the war: A wave of patriotism had swept the country in the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and thousands of young men across the country enlisted every day. McBurney was eager to do his part for the war effort. But he also saw the Army as an escape.

McBurney was born in Harlem on May 21, 1924. His parents divorced when he was very young; his mother moved away to Florida, and he saw her only rarely after that. He was raised by his father and stepmother. When he was twelve years old, his younger brother died of scarlet fever. Though devastated by the loss, McBurney did what he had watched his father do all his life: bury the pain deep inside, and keep moving.

William had always been in awe of his father. A smart, determined, and ambitious man, his father had been born dirt poor around the turn of the century in Titusville, Florida. Seeing no prospects for advancement there, he had worked his way north to New York City as a railroad porter. At the outbreak of World War I, he had volunteered for the Army, serving in a quartermaster unit in Europe. When he returned to New York, still searching for a means of steady employment and advancement, he had worked his way through school to become a dental technician. But in the 1920s it was very difficult for blacks to find work in professional jobs. With a young wife and a growing family to support, he had no choice but to turn to manual labor, working on the docks and, later, with the advent of the Great Depression, for the Civilian Conservation Corps, one of the massive public works programs started by the federal government.

William McBurney was an intelligent, active boy. Despite his large size, he was not coordinated or good at sports: His one physical gift was a powerful right hook. Though he never went out of his way to seek out a fight, neither did he ever turn away from one. He got into the usual number of scrapes for a kid in Harlem in the 1930s--often chasing or being chased by Italian kids from adjacent neighborhoods--but he was also always at one remove from whatever he was doing, thinking several steps ahead. He had already noticed the kinds of trouble young black men often got into, especially with the police, and he intended to avoid it. With his air of watchfulness, his quiet, steady intelligence, and his physical courage, he stood out in his group of friends as the one you wanted watching your back.

Like Smith and countless other African Americans at that time, McBurney was tracked early in his school career toward shop class, regardless of his intelligence or academic success. Given the options available to him at New York Vocational High School, like Leonard Smith he chose to study aviation mechanics. A female cousin was taking flying lessons at Floyd Bennet Field, and watching that plane take off and sail away made McBurney dream of becoming a pilot. But as time went on, it was a dream he seemed to have less and less hope of attaining. After school and on Saturdays he worked at a paintbrush factory for twenty-five cents an hour, helping his family to weather the Depression. Many of his friends had taken similar menial jobs. As high school graduation approached, many more of his friends, with no real opportunities for advancement, were falling into gambling and petty theft. McBurney saw himself and his friends moving steadily toward dead-end lives.

Like many young men, he had romanticized his father's service in World War I--the more so because his taciturn father never talked about it. He saw the Army as a way of creating a new life for himself, and of realizing his secret dream of flying. When he told his father he wanted to join the Army Air Corps, he was surprised to find his father immediately dismissive. He didn't believe the Air Corps would accept an African American. This only made McBurney more determined. Three days after his eighteenth birthday, he took the train to the recruitment center on Whitehall Street.

His father's warning about the Air Corps turned out to be all too true--as Leonard Smith had already discovered, no blacks were allowed to join. To McBurney, it was a slap in the face. Nonetheless, he decided to enlist. Like Smith, he had scored high marks on the Army's intelligence test. Though he also had no idea what a tank was, he found himself, like Smith, steered by the recruiter into armored.

After passing his physical and being given his shots, McBurney was sent by train with several other fresh recruits to Camp Upton, a processing center surrounded by open potato fields in Suffolk County, Long Island. Thousands of Army recruits would move through the sprawling complex between 1941 and 1945. The recruits spent two weeks living in tents, where they were given close haircuts, uniforms, and basic gear; then they were moved into barracks. They performed a series of marching and close-order drills each day, learning the basics of military procedure and decorum, as well as carrying out KP duty and cleaning the grounds of the camp. Finding themselves with a great deal of free time on their hands, they held a series of boxing and softball tournaments as they waited endlessly, it seemed to McBurney, for their orders to come. During orientation, they had seen motivational documentaries chronicling the reasons the country was at war, highlighting the battles that had been fought to date, and firing them up against Germany and Japan. All were eager to get overseas and get started. They wanted in on the action.

The close friendships that would characterize the men in combat were already begining to form. William McBurney first met Leonard Smith at Camp Upton. Despite, or perhaps because of, their vast temperamental differences--Smith was the sort who leapt before looking, while McBurney was the one who held back; Smith's humor tended toward open-hearted playfulness, McBurney's toward irony and observation--the two became fast friends. Soon they became close to another recruit as well, soft-spoken Preston McNeil.

Descriere

Inspired by a World War II veteran and friend, the basketball legend recounts the courageous story of the first all-black tank battalion to see combat in the war.