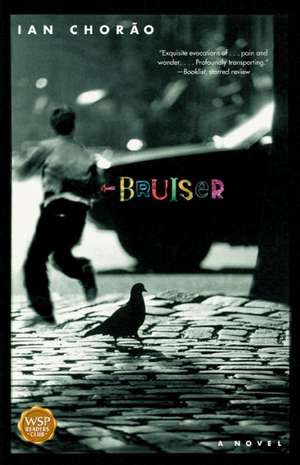

Bruiser: A Novel

Autor Ian Choraoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 mai 2004

This is Bruiser's tale in his own words, captured by first-time novelist Ian Chorão with uncanny precision and an ear for the staccato rhythms of childhood consciousness. Refreshingly free of sentimentality, Bruiser confronts the darkness and violence of life even as it illuminates its wonder and sweetness.

Preț: 147.69 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 222

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.26€ • 29.47$ • 23.49£

28.26€ • 29.47$ • 23.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 februarie-13 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743437769

ISBN-10: 0743437764

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.47 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0743437764

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.47 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Ian Chorão grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, like his main character. He lives in New York City with his wife and son.

Extras

Chapter One

Max is running toward us, across the overgrown grass, swinging a long rope round over his head. On the end is a black cat tied at the neck.

"Hee-haw!"

Behind, the line of buildings where we live face us sitting in the park. On the roof of one, a Big Kid leans out. With spray paint he finishes writing on the building's side: Weed -- Natures way of saying HIGH.

Max releases the rope. It goes through the air. The black cat's flopping legs rise up as it falls down toward the grass.

"Damn, Max!" Reid says. "That's nasty!"

"Yeah, Max: nasty!" Jimmy says.

Max's eyes are wild. "I told you I found a dead cat," he says. "Some voodoo shit, I guess."

Sometimes we find dead animals around Riverside Park. Regular dead kind: run-over pigeons, drowned bloated rats, and the voodoo kind: headless chickens, once a goat head.

We stand in a circle around the cat. I crouch for a closer look. Its mouth is open and a rough pink tongue sticks out. Its eyes are dry and sunken. I touch its stomach. They look away, tell me to stop.

"But, it's dead," I say.

"You're a diseased mother, now."

"I'm not."

"Ew, get away from him."

"That shit's bad luck," they say, which is true.

I pick up the rope and walk, the cat drags like a doll.

I swing the cat in a circle. The park blurs. I look into the cat's eyes. Everyone knows that black cats have powers, so I ask it telepathically to tell me what it knows. Where is its ghost? Where are its special powers? I spin too fast and my feet tangle. I tumble hard. On the ground I feel like I still spin. I dig my fingers into the earth to make it stop. Reid and Jimmy kneel on either side of me, take my arms, pin me down. Max dangles the dead cat overhead, right close to my face. Its tail brushes my cheek.

"Stop!"

Max lowers it more, dragging it over my face. Its claws scrape across my nose, my mouth, its head bouncing on a broken neck.

"Le'me go, le'me go, le'me go!"

Behind clouds curl like wings. Then I know: the cat made me fall.

I wrestle free, swinging my arms, stumbling up then back over on the slope. They laugh.

Max flings the dead cat over his shoulder into a bush. I sit with my back to them, plucking blades of grass. I stare into the sky.

This morning I overheard Mom talking to Dad. They talked in the hallway outside of the bathroom, standing next to the big clothes hamper, which I was lying inside of, before they came. Dad built it out of wood. It's good. Three feet high, longer than me, and just a bit wider than me. They talked about Granpa who's been sick forever with the cancer. Mom was in the bathroom all morning, and had just come out. Mom's been doing that a lot recently. I'll walk around, looking for her because I want waffles or grilled cheese, or to play Ouija, and I can't find her, and then I'll stand in front of the bathroom or her bedroom, and I'll hear her inside, making soft sounds. And I'll lie on my belly and watch the shadows she makes, and sometimes I'll see her feet, crouching in front of the toilet, and then violent splashing sounds, or feet across the floor into bed. Later when she's left, I'll lie in the bed and feel a wet spot on the pillow.

Mom said, He seems quite bad. And Dad said, Yes. Then Mom made bird sounds.

I had been lying in the clothes hamper for a long time and my legs had fallen asleep.

So you'll go down then? Dad asked. But Mom stayed quiet.

And my arms were also asleep, and my middle and my head were asleep, so when they came, my body had vanished, and deep below the clothes it was dark and the sounds soft. I stayed very still, knowing that the moment I moved I'd feel myself again.

I'm sorry, Dad said. Yes, Mom said.

Mom goes to Florida a lot. Until three years ago, when I turned six and started elementary school, I would go too. Now Mom leaves me alone with Dad and the brothers, Jordan and Daniel. I know I shouldn't, but sometimes I wish Granpa would die.

Then Mom said, Can't you...hold -- ? I heard the floor whine, Dad stepping forward. I heard clothes shuffle, two quick pats, then Dad's heavy footsteps walking away. Mom breathed a lot, then sat on top of the hamper.

That made me jerk and I felt my body again, the heavy smelly clothing on top of me warm from my breath. And suddenly I felt trapped, buried alive. I wanted to jump, to escape. I wanted to smell fresh air. I wanted to make a racket, to run.

But, I stayed very, very still.

Mom laughed. A tiny, funny laugh like she was laughing underwater.

"Ahh, yes," Jordan says. He lays his disco pants out on his bed below a polyester shirt with a photo print of a surfer. It's Saturday night and he's going to a party. I sit on the floor of the brothers' room and watch them.

"What's your curfew?" I ask.

"Scrub, I'm in the ninth grade. I'm not some little pea-head like you: what are you? in nursery school?"

"I'm not!"

"A-ha ha ha!"

Jordan, bored of me, turns away. Daniel hasn't looked over even once. Jordan runs his hands over the legs of the pants, smoothing them out. Daniel sits at his desk drawing. Music plays. Jordan, a towel around his waist from a shower, does a dance, pointing at his reflection, singing along.

"Shining Star for you to see, what your life can truly be."

I sing too.

"Shut up."

"What?"

"You wanna stay in here?"

I'm quiet. I walk to Daniel's desk. Dad gives Daniel drawing lessons. Dad has given him a little wooden man to practice with. His parts are different shapes: egg shape for the head, cylinders for the legs and arms, all flat and smooth, no eyes, no fingers. The man can be moved into different poses. Daniel has it running. I watch how he squints, looking from the man to his paper, quickly and lightly making the lines. I watch Daniel to see what it is that happens in the space between the little man and Daniel's eyes, that then runs down his arm to his hand that makes him draw so good. I get closer.

Daniel pushes at my face, but I don't move.

That is talent. Mom and Dad say so: Daniel has a natural talent for drawing. They say, Jordan has a talent for work, like how well he does in school.

Daniel pushes my face harder, mumbles, "Get away."

par

Then I feel Jordan from behind. He grabs my hair and drags me cross the room. He pushes me into the hallway, closes the door.

I go to my room. My window faces the courtyard. The left side is open air, far down the roofs of brownstones covered with white plastic chairs, trash: bottles, cigarette butts, pizza boxes. To the right are the windows into our dining room and kitchen. Mom and Dad are doing the dinner dishes. Dad washes and Mom dries and puts them away. I open the window. And right across the way are the apartments on the other side of the building. The one directly across is dark and has been empty for months. There are dried toilet paper bombs on the windows. I threw them. I was grounded because Dad caught me stealing two dollars from Mom's purse, because they were showing Tommy at the Thalia, and everyone but me saw it, and they were always singing, "Tommy, oo-oo-oo, Tommy can you hear me?" And Dad got extra mad when I told him why I stole the money because Dad had already told me that I couldn't see that sort of movie, that I was too young, and he didn't want to have to be coming into my bedroom at all hours of the night because of bad dreams. So he grounded me in my room for the day. No TV, no coming out except for meals, no dessert. He told me that I had to learn to make fun up for myself. So, I did. I used a whole roll, making the wads heavy with water.

Copyright © 2003 by Ian Chorão

Max is running toward us, across the overgrown grass, swinging a long rope round over his head. On the end is a black cat tied at the neck.

"Hee-haw!"

Behind, the line of buildings where we live face us sitting in the park. On the roof of one, a Big Kid leans out. With spray paint he finishes writing on the building's side: Weed -- Natures way of saying HIGH.

Max releases the rope. It goes through the air. The black cat's flopping legs rise up as it falls down toward the grass.

"Damn, Max!" Reid says. "That's nasty!"

"Yeah, Max: nasty!" Jimmy says.

Max's eyes are wild. "I told you I found a dead cat," he says. "Some voodoo shit, I guess."

Sometimes we find dead animals around Riverside Park. Regular dead kind: run-over pigeons, drowned bloated rats, and the voodoo kind: headless chickens, once a goat head.

We stand in a circle around the cat. I crouch for a closer look. Its mouth is open and a rough pink tongue sticks out. Its eyes are dry and sunken. I touch its stomach. They look away, tell me to stop.

"But, it's dead," I say.

"You're a diseased mother, now."

"I'm not."

"Ew, get away from him."

"That shit's bad luck," they say, which is true.

I pick up the rope and walk, the cat drags like a doll.

I swing the cat in a circle. The park blurs. I look into the cat's eyes. Everyone knows that black cats have powers, so I ask it telepathically to tell me what it knows. Where is its ghost? Where are its special powers? I spin too fast and my feet tangle. I tumble hard. On the ground I feel like I still spin. I dig my fingers into the earth to make it stop. Reid and Jimmy kneel on either side of me, take my arms, pin me down. Max dangles the dead cat overhead, right close to my face. Its tail brushes my cheek.

"Stop!"

Max lowers it more, dragging it over my face. Its claws scrape across my nose, my mouth, its head bouncing on a broken neck.

"Le'me go, le'me go, le'me go!"

Behind clouds curl like wings. Then I know: the cat made me fall.

I wrestle free, swinging my arms, stumbling up then back over on the slope. They laugh.

Max flings the dead cat over his shoulder into a bush. I sit with my back to them, plucking blades of grass. I stare into the sky.

This morning I overheard Mom talking to Dad. They talked in the hallway outside of the bathroom, standing next to the big clothes hamper, which I was lying inside of, before they came. Dad built it out of wood. It's good. Three feet high, longer than me, and just a bit wider than me. They talked about Granpa who's been sick forever with the cancer. Mom was in the bathroom all morning, and had just come out. Mom's been doing that a lot recently. I'll walk around, looking for her because I want waffles or grilled cheese, or to play Ouija, and I can't find her, and then I'll stand in front of the bathroom or her bedroom, and I'll hear her inside, making soft sounds. And I'll lie on my belly and watch the shadows she makes, and sometimes I'll see her feet, crouching in front of the toilet, and then violent splashing sounds, or feet across the floor into bed. Later when she's left, I'll lie in the bed and feel a wet spot on the pillow.

Mom said, He seems quite bad. And Dad said, Yes. Then Mom made bird sounds.

I had been lying in the clothes hamper for a long time and my legs had fallen asleep.

So you'll go down then? Dad asked. But Mom stayed quiet.

And my arms were also asleep, and my middle and my head were asleep, so when they came, my body had vanished, and deep below the clothes it was dark and the sounds soft. I stayed very still, knowing that the moment I moved I'd feel myself again.

I'm sorry, Dad said. Yes, Mom said.

Mom goes to Florida a lot. Until three years ago, when I turned six and started elementary school, I would go too. Now Mom leaves me alone with Dad and the brothers, Jordan and Daniel. I know I shouldn't, but sometimes I wish Granpa would die.

Then Mom said, Can't you...hold -- ? I heard the floor whine, Dad stepping forward. I heard clothes shuffle, two quick pats, then Dad's heavy footsteps walking away. Mom breathed a lot, then sat on top of the hamper.

That made me jerk and I felt my body again, the heavy smelly clothing on top of me warm from my breath. And suddenly I felt trapped, buried alive. I wanted to jump, to escape. I wanted to smell fresh air. I wanted to make a racket, to run.

But, I stayed very, very still.

Mom laughed. A tiny, funny laugh like she was laughing underwater.

"Ahh, yes," Jordan says. He lays his disco pants out on his bed below a polyester shirt with a photo print of a surfer. It's Saturday night and he's going to a party. I sit on the floor of the brothers' room and watch them.

"What's your curfew?" I ask.

"Scrub, I'm in the ninth grade. I'm not some little pea-head like you: what are you? in nursery school?"

"I'm not!"

"A-ha ha ha!"

Jordan, bored of me, turns away. Daniel hasn't looked over even once. Jordan runs his hands over the legs of the pants, smoothing them out. Daniel sits at his desk drawing. Music plays. Jordan, a towel around his waist from a shower, does a dance, pointing at his reflection, singing along.

"Shining Star for you to see, what your life can truly be."

I sing too.

"Shut up."

"What?"

"You wanna stay in here?"

I'm quiet. I walk to Daniel's desk. Dad gives Daniel drawing lessons. Dad has given him a little wooden man to practice with. His parts are different shapes: egg shape for the head, cylinders for the legs and arms, all flat and smooth, no eyes, no fingers. The man can be moved into different poses. Daniel has it running. I watch how he squints, looking from the man to his paper, quickly and lightly making the lines. I watch Daniel to see what it is that happens in the space between the little man and Daniel's eyes, that then runs down his arm to his hand that makes him draw so good. I get closer.

Daniel pushes at my face, but I don't move.

That is talent. Mom and Dad say so: Daniel has a natural talent for drawing. They say, Jordan has a talent for work, like how well he does in school.

Daniel pushes my face harder, mumbles, "Get away."

par

Then I feel Jordan from behind. He grabs my hair and drags me cross the room. He pushes me into the hallway, closes the door.

I go to my room. My window faces the courtyard. The left side is open air, far down the roofs of brownstones covered with white plastic chairs, trash: bottles, cigarette butts, pizza boxes. To the right are the windows into our dining room and kitchen. Mom and Dad are doing the dinner dishes. Dad washes and Mom dries and puts them away. I open the window. And right across the way are the apartments on the other side of the building. The one directly across is dark and has been empty for months. There are dried toilet paper bombs on the windows. I threw them. I was grounded because Dad caught me stealing two dollars from Mom's purse, because they were showing Tommy at the Thalia, and everyone but me saw it, and they were always singing, "Tommy, oo-oo-oo, Tommy can you hear me?" And Dad got extra mad when I told him why I stole the money because Dad had already told me that I couldn't see that sort of movie, that I was too young, and he didn't want to have to be coming into my bedroom at all hours of the night because of bad dreams. So he grounded me in my room for the day. No TV, no coming out except for meals, no dessert. He told me that I had to learn to make fun up for myself. So, I did. I used a whole roll, making the wads heavy with water.

Copyright © 2003 by Ian Chorão