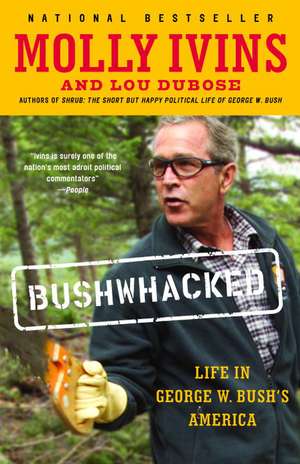

Bushwhacked: Life in George W. Bush's America

Autor Molly Ivins, Lou Duboseen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2004

Preț: 88.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.89€ • 17.53$ • 14.08£

16.89€ • 17.53$ • 14.08£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375713118

ISBN-10: 0375713115

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375713115

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Molly Ivins’s column is syndicated to more than three hundred newspapers from Anchorage to Miami. A three-time Pulitzer Prize finalist, she is the former co-editor of The Texas Observer and the former Rocky Mountain bureau chief for The New York Times. Her freelance work has appeared in Esquire, The Atlantic Monthly, The New York Times Magazine, The Nation, Harper’s Magazine, and other publications. She has a B.A. from Smith College and a master’s in journalism from Columbia University. Her first book, Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She?, spent more than twelve months on the New York Times bestseller list.

Lou Dubose has worked as a journalist in Texas for twenty years. He has been editor of The Texas Observer and politics editor of The Austin Chronicle, and is the co-author of Boy Genius: Karl Rove, the Brains Behind the Remarkable Political Triumph of George W. Bush. His freelance work has appeared in The Nation, Texas Monthly, The Washington Post, the Toronto Globe and Mail, the Liberty, Texas, Vindicator, and other publications. He is currently working on a book about Tom Delay. He lives with his wife, Jeanne Goka, in Austin.

Lou Dubose has worked as a journalist in Texas for twenty years. He has been editor of The Texas Observer and politics editor of The Austin Chronicle, and is the co-author of Boy Genius: Karl Rove, the Brains Behind the Remarkable Political Triumph of George W. Bush. His freelance work has appeared in The Nation, Texas Monthly, The Washington Post, the Toronto Globe and Mail, the Liberty, Texas, Vindicator, and other publications. He is currently working on a book about Tom Delay. He lives with his wife, Jeanne Goka, in Austin.

Extras

1.

Aloha, Harken

In the long run, there is no capitalism without conscience; there is no wealth without character.

—George W. Bush on Wall Street, July 9, 2001

In the long run, we are all dead.

—John Maynard Keynes on the long run, 1924

There he was. On the Tuesday after a long Fourth of July weekend. In the ballroom of an ornate Wall Street hotel that once housed the New York Merchants Exchange. Standing in front of a blue-and-white backdrop with the words corporate responsibility printed over and over on it, in case you should miss the point. Promising us “a new ethic” for American business. Our president, Scourge of Corporate Misbehavior.

It was like watching a whore pretend to be dean of Southern Methodist University’s School of Theology. But as Luther said, hypocrisy has ample wages.

“Harken,” said the Bush camp over and over, “was nothing like Enron.” Interestingly enough, it was exactly like Enron in each and every feature of corporate misbehavior, except a lot smaller. A perfect miniature Enron.

By the summer of 2002, it had long been known that twelve years earlier Bush made a pile by selling his stock in Harken Energy Corporation just before it tanked. At the time, he was serving both on Harken’s board and on a special audit committee looking at the company’s financial health. As he spoke on Wall Street, stories were surfacing about Harken’s sham sale of a subsidiary to a group of company insiders. The acquisition was financed by an $11 million loan guaranteed by the seller, Harken Energy. In other words, a fake asset swap to punch up Harken’s annual profit-and-loss statement.

The “sale” of Aloha Petroleum, from Harken to Harken, was again Enron writ small and so outrageous that the SEC stepped in, declared the accounting unacceptable, and forced the company to restate its earnings. Bush unquestionably knew about the deal.

Even if he had convinced the public that earlier stories about his $848,560 insider trade, his failure to report it to the SEC, his low-interest loans from Harken to buy company stock (a practice he particularly denounced in his Wall Street speech, as though he had never heard of such an unseemly scam before), and the Enron-esque sale of Aloha Petroleum were all what he described as “recycled stuff,” he was still surrounded by bad stories about to break. Enron was ripe for federal prosecution; Bush and Enron’s CEO, Ken Lay, his single largest campaign contributor, had been tight for years. Halliburton was being investigated by the feds for fraudulent accounting practices put in place when Dick Cheney was CEO. Congress was investigating the secretary of the Army for his role in the collapse of Enron, in the fleecing of electricity customers in California, and for his failure to divest himself of Enron stock in a timely manner.

SEC chief Harvey Pitt had so many previous business connections with the firms he was now regulating, he had already had to recuse himself in twenty-nine cases being pursued by the SEC. Bush’s hard-nosed, hard-assed political adviser, Karl Rove, had owned $108,000 in Enron stock and, more important, knew the Enron CEO because he was Bush’s biggest funder. Two of Bush’s economic advisers had worked as consultants for Enron. And the newly disgraced Ken Lay had convinced Bush to dump the chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Curtis Hebert, and to replace him with the candidate of Lay’s choice, a Port Arthur, Texas, homeboy. Before giving Bush the word to dump Hebert, Lay had a come-to-Jesus session with Hebert himself, telling him to embrace free markets and deregulation or, Lay said, things would end badly for Hebert. They did.

Considering the circumstances, heckfire and brimpebbles were the best GeeDubya could manage as he wagged his fingers at Wall Street’s corporate criminals. What could he say about Lay: “I never had sexual relations with that man”? What he actually said, as the cock crowed, was, “He was an Ann Richards supporter.” Kenny Boy, I hardly knew ye.

The stock markets responded to Bush in July as they had to bin Laden in September. Three days after Bush’s Sermon on Wall Street, the Dow Jones had lost 7.4 percent of its value and Standard & Poor’s 500 was down 6.8 percent. Three weeks after the speech, with more Harken stuff breaking, the market fell 390 points in one day. It took a corporate-responsibility bill—written entirely by Democratic senator Paul Sarbanes and vigorously opposed by Bush almost until the day it was passed unanimously by the House—to save the president and staunch the stock market’s hemorrhaging.

The Bushies naturally would have preferred to put all this “recycled stuff” behind them and return to their agenda—including shifting Social Security funds into the stock market. But before we leave the subject, consider some wisdom from Jerry Jeff Walker, the Texas singer-songwriter. Walker met the man who inspired his first hit, “Mr. Bojangles,” when they were both in jail in New Orleans. Years later, a reporter for National Public Radio asked Walker if he had worried about winding up in a drunk tank when he was in his early twenties. “No,” Walker said. “It was just one time. You start worryin’ when there’s a pattern.”

With GeeDubya Bush, M.B.A., there was a pattern. The pattern was: after he fouled up, a friend of Daddy’s always showed up to bail him out. Either because Bush managed to seduce the press corps in 2000 or because Al Gore failed to raise the issue, the press started to notice Bush’s business pattern only in the wake of the wrecks of Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, Adelphia, etc. As the economy contracted and stock values plummeted in mid-2002, reporters began to focus on Bush’s M.O.

Bush walked away from the Texas “awl bidness” in 1990 with almost a million in cash—after a career during which he lost more than $3 million of other people’s money. Here he was advocating “a new ethic” on Wall Street despite his own business dealings, which couldn’t even pass the “old ethic” test. The earlier dealings had been the subject of a pro forma investigation directed by the man President Bush the Elder appointed head of the SEC, and the investigation itself was conducted by a man who had worked as GeeDubya’s personal lawyer before joining the SEC. A few of GeeDubya’s deals, particularly a series of critical bailouts of his ever-sinking oil-field ventures, are truly astonishing—not just because of the volume of dollars flowing out of Northeastern banks and disappearing in Texas but because the transactions made little or no economic sense.

A company balance sheet can be misleading. There was leaseholds, there was momentum.

—candidate george w. bush on philip uzielli’s $1 million bailout of arbusto

One of Bush’s white knights, a friend of the Bush family consigliere* James Baker III, is so interesting that to leave him out is the journalistic equivalent of a breach of fiduciary responsibility. Philip Uzielli’s $1 million cash-for-trash deal in 1982 allowed GeeDubya to keep his company alive long enough to sell it to Spectrum 7, then to sell the again-sinking Spectrum 7 to Harken and then to unload his sinking Harken stock—just before the bad news became public—for a large enough profit to buy 2 percent of the ownership of a baseball franchise that made him $15 million in less than nine years. Philip Uzielli (“Uzi” to GeeDubya) is a Panamanian businessman and Princeton classmate of James Baker. In 1982 he was listed as CEO of Panama’s Executive Resources and as a director of Harrow Corporation and Leigh Products. As we reported in Shrub, when GeeDubya’s company, Arbusto, was in a terminal cash crunch, Uzi showed up and paid $1 million for 10 percent of a failing company valued at $382,376, according to the company’s financial statements. In other words, Uzielli paid $1 million for $38,200 in equity. Bush had changed the name of Arbusto to Bush Exploration after his father became vice president. (GeeDubya says arbusto is the Spanish word for “bush,” although Cassell’s Spanish/English Dictionary translates it as “shrub,” the source of one of GeeDubya’s nicknames.) By the time of the corporate name change, Arbusto had drilled so many dry holes that West Texas oilmen called it “are-busted.” Mr. Uzielli lost his entire $1 million investment but later told reporters he didn’t regret it. He described his investment with Bush as “a losing wicket” but said “it was great fun.” What a sport.

Arbusto was not an oil company so much as it was a tax write-off company, taking advantage of the IRS tax-code provision that allowed investors to deduct up to 75 percent of their losses in the

*Maureen Dowd, columnist for The New York Times, was apparently the first journalist to use the word consigliere to describe Baker’s role in the Bush family.

oil business. Bush didn’t strike oil, he struck money from friends of his daddy. After the Uzielli bailout Bush Exploration was acquired by Spectrum 7. Spectrum 7 was owned by William DeWitt, Jr., son of the owner of the Cincinnati Reds. DeWitt couldn’t pay Bush for what remained of Bush Exploration, so he sort of took him in, made him CEO and a director, paid him $75,000 a year and $120,000 in consulting fees, and gave him 1.1 million shares of Spectrum 7 stock.

Two years later Spectrum 7 had lost $400,000 in six months and was $3 million in debt. So Harken stepped in. The Texas-based company bought Spectrum 7 for $2 million in Harken stock. Of the $2 million, $224,000 in shares went to Bush, along with options to purchase more.

There was no malfeeance [sic], nor attempt to hide anything. In the corporate world, sometimes things aren’t exactly black and white when it comes to accounting procedures.

—president george w. bush, july 8, 2002, on absence of “malfeeance” in the aloha sale

“His name was George Bush,” said Harken’s founder, Phil Kendrick. “That was worth the money they paid him.” Oil-field losses followed GeeDubya the way that cloud of dirt used to follow Pig Pen in “Peanuts.” By 1989 Harken was booking big losses but Daddy was president. In February 1990 the company’s CEO, Mikel Faulkner, warned board members that a failed deal the previous year left the company “with little cash flow flexibility.” In the months that followed, Harken’s memos and board minutes should have been written in red ink. So the management team devised a scheme to obscure these losses.

See if you can follow this bouncing ball. Harken masked its 1989 losses by selling 80 percent of a subsidiary, Aloha Petroleum, to a partnership of Harken insiders called International Marketing & Resources for $12 million. Of that sum, $11 million came from a note held by Harken. Aloha was a small chain of gas stations and convenience stores in Hawaii, originally started by J. Paul Getty and acquired by Harken in a package deal in 1986.

When Harken sold Aloha in 1989, here’s how it did the accounting. Since Harken carried an $11 million note on the $12 million sale, the only money it got up front was the first $1 million. But Harken booked $7.9 million, using the mark-to-market accounting that Enron made so fashionable in the late nineties. In January 1990, IMR in turn sold its stake in Aloha to a privately held company called Advance Petroleum Marketing, and the Harken loan was effectively transferred to Advance.

In brief, Harken insiders borrowed money from their own company to buy a subsidiary at an inflated price. Then they booked sales revenue that didn’t exist as profit. Then they got rid of the loan that had provided the revenue that never really existed. This is the kind of deal that made Enron famous. It allowed Harken to declare a modest loss of $3.3 million on its 1989 annual report, and as a result the company’s shareholders had no clue how bad things were. And we all thought the smart guys at Enron invented those clever transactions.

By 1990 Harken’s management realized that the accounting in their sale of Aloha wasn’t quite right. Their thinking on the subject had been clarified after what they described as “discussions” with the SEC. Actually, the SEC flatly declared the sale bogus. When Harken applied the standard “cost recovery” method of accounting required by the SEC, its 1988 losses suddenly became $12.57 million. It is remarkable what can be achieved by just a little attention from a federal regulatory agency. The same stan- dard accounting practices applied to 1989 showed the company had lost $3.3 million over the first three quarters, whereas the “aggressive accounting” originally applied by Harken gave them a $4.6 million profit for the period. Harken’s accounting firm was Arthur Andersen.

Any time an officer of a publicly held corporation sells stock, we ought to know within two days. We ought to know. We being shareholders and employees.

—george w. bush on wall street, july 9, 2002

Harken’s sham sale of Aloha was a shameful violation of shareholder trust, but it kept Harken’s share value up long enough to let Bush sell his stock before the corrected profit-and-loss statements were released in August. The press seemed to prefer the stock-sale story because it is easier to explain than the Aloha deal. As reporters began to press harder on the issue, even the un- flappable Ari Fleischer began to flap. “The SEC has been well aware of the issue and the SEC has concluded that this is not anything that’s actionable,” said Fleischer in early July. Bush too became testy, telling reporters that if they wanted more information they should get the minutes of Harken’s board of directors’ meetings. Harken refused to release the minutes. The story might have stalled there had it not been for the work of Charles Lewis and the Center for Public Integrity. The Washington, D.C.–based public-interest group obtained Harken board minutes and correspondence through a Freedom of Information Act request to the SEC. Then they did what both President Bush and his SEC chairman, Harvey Pitt, had refused to do: they made the documents public by putting them on the center’s website (www.publici.org).

You don’t need an accountant to interpret the Harken documents. The company was in desperate trouble. At a May 1990 meeting attended by Bush, board members discussed a stock offering they hoped would bring in enough money to keep the company solvent. Bush was named to the board’s “Fairness Committee,” which was to measure the effects of bankruptcy on small stockholders. Ever the populist, GeeDubya said at this meeting “that inherent in these principles must be the interests and preservation of value for the small shareholder of the company.” A month later Bush left the small shareholders holding the bag; he dumped $848,560 of the stock without disclosing the sale to the SEC. The purpose of the SEC’s disclosure rule is precisely to inform all shareholders that something may be wrong—by letting them know when someone with inside information sells a large block of stock.

The Harken memos show just how much Bush knew about the company’s dicey finances. By late May 1990, internal company memos warned that there was no other source of immediate financing, that a cash crunch was only days away, and that loans were slipping “out of compliance.” Banks were demanding guarantees of sufficient equity to cover the notes. As chairman of the audit committee actually working with the accounting consultants called in by the board, Bush knew exactly how grim their conclusions were. He was warned, along with other directors, in a May 25 memo that it would be illegal to dump his stock. He sold in June to a private purchaser who has never been identified.

The company was kept afloat by investments from a small liberal-arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This news was revealed only after a group of dogged and enterprising Harvard students at the nonprofit HarvardWatch dug into records there and turned their findings over to The Wall Street Journal in 2002.

Harvard’s Harken bailout helped salvage Bush’s last shaky oil company, at one time setting up a Harvard-Harken venture that moved $20 million in liabilities off Harken’s books. It also cost the university’s endowment more money than the young Bush ever earned in West Texas. Hooking up with Harken contributed to a record $200 million write-down for Harvard Management in 1991. Why did Harvard do it? Let us count the ways. Harvard Management exec Michael Eisenson sat on Harken’s board with Dubya Bush. George Herbert Walker Bush was vice president of the United States—and a Skull and Bones Yalie. His son held a Harvard Business School M.B.A.—and was a Skull and Bones Yalie. After Poppy became president and tiny Harken somehow secured a huge drilling contract in Bahrain, Harvard kept pouring millions into the little Texas oil company in ’89, ’90, and ’91.

In July 2002 the White House offered three explanations for Bush’s failure to report his own Harken stock sale. The first was that the filing of the disclosure form was “the corporation’s responsibility.” A letter from Harken’s general counsel dated October 5, 1989, gently reminds Bush that he had failed to file the same Form 4 when he exercised his director’s option to buy 25,000 shares of Harken stock exactly one year before he unloaded it in June 1990. The “Dear George” letter from Harken’s general counsel, Larry Cummings, made it clear to Bush that company lawyers or accountants couldn’t file the forms because they required his signature.

Turns out Bush regularly failed to report insider dealings to the SEC. On two occasions before his June 1990 stock dump,

Bush had sold as a board member and failed to file the disclosure forms.

There are countless subjects on which George W. Bush might have pleaded ignorance in 1990, but a failing oil business was not one of them. At the end of 1989 Harken president Mikel Faulkner told a reporter at the Petroleum Review that Harken would book more than $6 million in end-of-the-year profits. On August 22, 1990, Harken’s second-quarter report predicted $23.2 million in losses. Once the news hit the street, the stock sank immediately from $4 to $2.37; it later bottomed out at twenty-two cents a share.

Eight and a half months later The Wall Street Journal reported that the president’s son was under investigation for failure to report the stock sales. The chairman of the SEC was Richard Breeden, who had worked for Poppy Bush as an economic adviser. The walls of Breeden’s office were so plastered with photos of Poppy and Barbara Bush that a New York Times reporter observed, “George Bush is Breeden’s Mao.” The general counsel at the SEC was James Doty, the same James Doty of the Baker Botts law firm, who represented GeeDubya when he bought his 2 percent interest in the Texas Rangers with the money he got from dumping his Harken stock. The Houston law firm was founded by the great-grandfather of James Baker III, secretary of state under Bush the Elder and the point man for Bush the Younger in Florida after the disputed 2000 election.

Breeden and Doty never asked for an interview with the subject of their investigation. Since 1993 Breeden, Doty, and other partners of Baker Botts have contributed $210,621 to GeeDubya’s political campaigns, making the firm the president’s number-fourteen career patron. They were beaten out for the number-thirteen spot by Arthur Andersen, at $220,557.

In a letter regarding “George W. Bush Jr.’s [sic] Filings,” SEC investigators observed that Bush was familiar with the SEC’s filing deadlines, having met them when he filed reports of dealings with three other companies in which he owned stock. But with Harken, Bush filed “four late Forms 4 reporting four separate transactions, totaling $1,028,935.” During his first campaign for governor of Texas, Bush repeatedly told reporters he had been “exonerated” by the SEC, and Fleischer repeated the same line in the summer of ’02. But the report issued by the SEC’s enforcement division in 1993 specifically says the investigation “must in no way be construed as indicating that the party has been exonerated.”

Just as Harken was selling itself its own subsidiary in Hawaii, it set up another corporation on another island. Harken Bahrain Oil company registered in the Cayman Islands in September 1989. The Caymans, like Bermuda, are a convenient offshore address for U.S. companies that want to do business at home but prefer not to pay U.S. taxes. After the furor over tax-dodging corporations broke, Bush made this ringing statement in August 2002: “We ought to look at people who are trying to avoid U.S. taxes as a problem.” Corporate tax dodgers now cost the country seventy billion dollars annually, according to the IRS, all of which has to be made up by average citizens who can’t acquire a mail drop in the Caymans. The Scourge of Corporate Misbehavior even daringly urged corporate tax-dodgers to “pay taxes and be good citizens.” Then the White House had to acknowledge that Harken Energy had set up an offshore subsidiary to avoid taxes. Bad timing.

Harken was not Enron, but it was certainly Enron in the making. What Bush took out of Harken was also twenty times as much as Bill and Hillary Clinton lost in a crummy Arkansas real estate deal that cost American taxpayers seventy million dollars to investigate. By the time Bush signed the Corporate Responsibility Act, Harken was selling at forty-one cents a share. Don’t put your Social Security money in it.

So who are the “regular folks” who have been affected here, and what have those effects been? In this chapter, you, dear readers, are the regular folks. Americans lost $6 trillion when the stock market collapsed after Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco. It’s your 401(k) that’s the subject here, your pension, your Social Security, your investments, your savings, and your jobs. You.

Of course George W. Bush and his petty self-dealing at Harken did not cause the collapse of Enron et al. What we are looking at is not causation but connection. If one wanted to paint with a broad brush, surely Bill Clinton, president during the enormous stock market boom of the second half of the nineties, has more responsibility for the eventual collapse than does George W., president for only eighteen months when it happened.

But an even broader brush shows a different pattern. Start- ing in 1980 with the presidency of Ronald Reagan (or even the 1978 deregulation of the airlines, if you’d like to include Jimmy Carter), this country has been going through a deregulatory mania. Supply-siders, Milton Friedman, free-marketeers of all stripes, “movement conservatives,” The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page—not to mention a motley assortment of anti-government cranks from militias to Republican candidates—have been trying to persuade us that government can’t do a damn thing right and that free markets are the answer to absolutely everything. There’s a true-believerism about the free-marketeers that is genuinely unsettling, as though it were a cult or a religion in which certain fundamental assumptions are never questioned. All you have to do to believe is ignore history and experience.

Capitalism is a marvelous system for creating wealth. On the other hand, unregulated capitalism creates hideous social injustice and promptly destroys itself with greed. A marketplace needs rules. From the very beginning, capitalism has required careful regulation. In the market towns of medieval England there were as many as twenty or thirty laws governing just the balance scales, and whether you could put your thumb or any other digit on the scale. Mostly what we’ve learned from the American experiment is that competition is good, but we need rules because people cheat. And there are some natural monopolies that need regulation or they end up in cartels that rip everybody off.

Government regulation and the much-maligned trial lawyers are the two instruments by which we control corporate greed. It seems to me government is neither good nor bad but simply a tool, like a hammer. You can use a hammer to build with, or you can use a hammer to destroy with. The virtue of the hammer depends on the purposes to which it is put and the skill with which it is used.

Of course government regulation is burdensome and often absurd. One famous federal form required employers to “list your employees broken down by sex.” “None,” read one reply. “Alcohol is our problem.”

What has changed in this country over the course of the past twenty-some years is that government has served less and less as a brake on corporate behavior and more and more as a corporate auxiliary, because of the corrupting effects of the system of legalized bribery we call “campaign financing.”

And here we find the root cause of the stock market collapse. During the nineties the SEC was increasingly starved for funds by the Republican Congress on the grounds that regulation is bad, and so it suffered a tremendous erosion of its authority. While the press was telling the Enron disaster story and CEOs were stepping forward like Baptists at an altar call to restate their companies’ earnings, Bush fought for a bare-bones SEC budget, recommending $576 million in July 2002. (The House autho- rization at the time was $776 million.) Clinton’s SEC appointee, Arthur Levitt, had struggled valiantly for such obvious reforms as expensing stock options and monitoring accounting firms, but the politicians paid no attention during the years of go-go and the all-absorbing crisis over the president’s sex life.

Phil and Wendy Gramm made a significant husband-and-wife contribution to the mess. In 1992, just a few days after Bill Clinton’s election, Wendy Gramm, in her last days as the lame-duck chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Corporation (which was short two of its five members), pushed through a federal rule that exempted energy-derivatives contracts from federal regulation (because regulation is bad).* Energy derivatives were just then becoming one of Enron’s most profitable lines. According to Robert Bryce’s book on Enron, Pipe Dreams, this key piece of deregulation is what allowed Enron to become a giant in the derivatives business. The exemption not only prevented federal oversight, exempting the companies from the CFTC’s authority, it even exempted them if the contracts they were selling were designed to defraud or mislead buyers. Five weeks later Enron announced it was hiring Mrs. Gramm as a member of the Enron board, a job that eventually paid her about $1 million in salary, attendance fees, stock-option sales, and dividends. Senator Phil Gramm’s Banking Reform Act formally repealed the long-standing prohibition (which grew out of the stock crash of ’29) against merging banks, brokerage houses, and insurance companies. Then the IRS was emasculated by Gingrich Republicans on the grounds that collecting taxes is tantamount to fascism.

The whole dizzying array of corporate clout-wielders in Washington—powerful lobbyists who leave no fingerprints on curious little exemptions and special provisions that apply to only one company—gets larger and more brazen by the year.

George W. Bush didn’t invent any of this. His role is to pretty much embody it. He is what people mean when they speak of “crony capitalism.” His administration is what we mean by the cliché “setting the fox to guard the hen coop.” (Raccoons are actually far more dangerous to chickens—take our word for it.) Bush is

*The commission rule became known as the Enron exemption when it was passed into law in 2001, advanced by (Mr. Wendy) Phil Gramm, who chaired the Senate Banking Committee.

not motivated by greed—he honestly believes government should be an adjunct of corporate America and that we’ll all be better off if it is. Thus his role has been to build upon, to extend, to exaggerate, to further privatize, to cheerlead for, to evangelize about all that the free-marketeers have been preaching over the years.

The odd thing about Bush at midterm is that most of the Washington press corps has yet to recognize just how extreme his ideology is. As governor of Texas he tried to privatize the state welfare system and considered privatizing the University of Texas; he fought for “voluntary compliance” with environmental regulations. With the power of large corporations in this country already grossly disproportionate because of their influence over politicians through money, government is the last effective check on corporate greed. To put a man in charge of the government who basically doesn’t believe it should play a role is folly.

The tragedy of having him in office at this time is that the man is congenitally incapable of checking the excesses of capitalism. No sooner was the Sarbanes bill passed than Bush’s man, at the SEC Harvey Pitt, busily began undermining it. Pitt’s claim to the title of biggest raccoon in the henhouse is rivaled only by the perfectly ludicrous appointment Bush made to the board assigned to implement the new McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reforms—a man vehemently opposed to campaign-finance reform. There are contenders at Interior, Labor, and EPA as well, but Pitt probably deserves the prize. Pitt wanted to appoint Judge William Webster to head the new accounting firm oversight board set up by the Sarbanes bill. Webster turned out to have corporate conflicts of interest out the wazoo, and Pitt himself was fired as a result. However, he remained on the job and by January 2003 had managed to actually weaken the rules that had been in effect before the corporate scandals broke. So many fundamental reforms have not been addressed—the failure to count stock options as a business expense, which gives CEOs an incentive to run up stock prices with tricky accounting; out-of-control hedge funds; derivatives; directors with conflicts of interest; the list goes on. Less than nothing has been done about any of it, so one can guarantee this whole corporate-fraud fiasco is going to happen again.

George W. Bush should declare himself a conscientious objector in his own war on corporate crime.

Aloha, Harken

In the long run, there is no capitalism without conscience; there is no wealth without character.

—George W. Bush on Wall Street, July 9, 2001

In the long run, we are all dead.

—John Maynard Keynes on the long run, 1924

There he was. On the Tuesday after a long Fourth of July weekend. In the ballroom of an ornate Wall Street hotel that once housed the New York Merchants Exchange. Standing in front of a blue-and-white backdrop with the words corporate responsibility printed over and over on it, in case you should miss the point. Promising us “a new ethic” for American business. Our president, Scourge of Corporate Misbehavior.

It was like watching a whore pretend to be dean of Southern Methodist University’s School of Theology. But as Luther said, hypocrisy has ample wages.

“Harken,” said the Bush camp over and over, “was nothing like Enron.” Interestingly enough, it was exactly like Enron in each and every feature of corporate misbehavior, except a lot smaller. A perfect miniature Enron.

By the summer of 2002, it had long been known that twelve years earlier Bush made a pile by selling his stock in Harken Energy Corporation just before it tanked. At the time, he was serving both on Harken’s board and on a special audit committee looking at the company’s financial health. As he spoke on Wall Street, stories were surfacing about Harken’s sham sale of a subsidiary to a group of company insiders. The acquisition was financed by an $11 million loan guaranteed by the seller, Harken Energy. In other words, a fake asset swap to punch up Harken’s annual profit-and-loss statement.

The “sale” of Aloha Petroleum, from Harken to Harken, was again Enron writ small and so outrageous that the SEC stepped in, declared the accounting unacceptable, and forced the company to restate its earnings. Bush unquestionably knew about the deal.

Even if he had convinced the public that earlier stories about his $848,560 insider trade, his failure to report it to the SEC, his low-interest loans from Harken to buy company stock (a practice he particularly denounced in his Wall Street speech, as though he had never heard of such an unseemly scam before), and the Enron-esque sale of Aloha Petroleum were all what he described as “recycled stuff,” he was still surrounded by bad stories about to break. Enron was ripe for federal prosecution; Bush and Enron’s CEO, Ken Lay, his single largest campaign contributor, had been tight for years. Halliburton was being investigated by the feds for fraudulent accounting practices put in place when Dick Cheney was CEO. Congress was investigating the secretary of the Army for his role in the collapse of Enron, in the fleecing of electricity customers in California, and for his failure to divest himself of Enron stock in a timely manner.

SEC chief Harvey Pitt had so many previous business connections with the firms he was now regulating, he had already had to recuse himself in twenty-nine cases being pursued by the SEC. Bush’s hard-nosed, hard-assed political adviser, Karl Rove, had owned $108,000 in Enron stock and, more important, knew the Enron CEO because he was Bush’s biggest funder. Two of Bush’s economic advisers had worked as consultants for Enron. And the newly disgraced Ken Lay had convinced Bush to dump the chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Curtis Hebert, and to replace him with the candidate of Lay’s choice, a Port Arthur, Texas, homeboy. Before giving Bush the word to dump Hebert, Lay had a come-to-Jesus session with Hebert himself, telling him to embrace free markets and deregulation or, Lay said, things would end badly for Hebert. They did.

Considering the circumstances, heckfire and brimpebbles were the best GeeDubya could manage as he wagged his fingers at Wall Street’s corporate criminals. What could he say about Lay: “I never had sexual relations with that man”? What he actually said, as the cock crowed, was, “He was an Ann Richards supporter.” Kenny Boy, I hardly knew ye.

The stock markets responded to Bush in July as they had to bin Laden in September. Three days after Bush’s Sermon on Wall Street, the Dow Jones had lost 7.4 percent of its value and Standard & Poor’s 500 was down 6.8 percent. Three weeks after the speech, with more Harken stuff breaking, the market fell 390 points in one day. It took a corporate-responsibility bill—written entirely by Democratic senator Paul Sarbanes and vigorously opposed by Bush almost until the day it was passed unanimously by the House—to save the president and staunch the stock market’s hemorrhaging.

The Bushies naturally would have preferred to put all this “recycled stuff” behind them and return to their agenda—including shifting Social Security funds into the stock market. But before we leave the subject, consider some wisdom from Jerry Jeff Walker, the Texas singer-songwriter. Walker met the man who inspired his first hit, “Mr. Bojangles,” when they were both in jail in New Orleans. Years later, a reporter for National Public Radio asked Walker if he had worried about winding up in a drunk tank when he was in his early twenties. “No,” Walker said. “It was just one time. You start worryin’ when there’s a pattern.”

With GeeDubya Bush, M.B.A., there was a pattern. The pattern was: after he fouled up, a friend of Daddy’s always showed up to bail him out. Either because Bush managed to seduce the press corps in 2000 or because Al Gore failed to raise the issue, the press started to notice Bush’s business pattern only in the wake of the wrecks of Enron, Tyco, WorldCom, Adelphia, etc. As the economy contracted and stock values plummeted in mid-2002, reporters began to focus on Bush’s M.O.

Bush walked away from the Texas “awl bidness” in 1990 with almost a million in cash—after a career during which he lost more than $3 million of other people’s money. Here he was advocating “a new ethic” on Wall Street despite his own business dealings, which couldn’t even pass the “old ethic” test. The earlier dealings had been the subject of a pro forma investigation directed by the man President Bush the Elder appointed head of the SEC, and the investigation itself was conducted by a man who had worked as GeeDubya’s personal lawyer before joining the SEC. A few of GeeDubya’s deals, particularly a series of critical bailouts of his ever-sinking oil-field ventures, are truly astonishing—not just because of the volume of dollars flowing out of Northeastern banks and disappearing in Texas but because the transactions made little or no economic sense.

A company balance sheet can be misleading. There was leaseholds, there was momentum.

—candidate george w. bush on philip uzielli’s $1 million bailout of arbusto

One of Bush’s white knights, a friend of the Bush family consigliere* James Baker III, is so interesting that to leave him out is the journalistic equivalent of a breach of fiduciary responsibility. Philip Uzielli’s $1 million cash-for-trash deal in 1982 allowed GeeDubya to keep his company alive long enough to sell it to Spectrum 7, then to sell the again-sinking Spectrum 7 to Harken and then to unload his sinking Harken stock—just before the bad news became public—for a large enough profit to buy 2 percent of the ownership of a baseball franchise that made him $15 million in less than nine years. Philip Uzielli (“Uzi” to GeeDubya) is a Panamanian businessman and Princeton classmate of James Baker. In 1982 he was listed as CEO of Panama’s Executive Resources and as a director of Harrow Corporation and Leigh Products. As we reported in Shrub, when GeeDubya’s company, Arbusto, was in a terminal cash crunch, Uzi showed up and paid $1 million for 10 percent of a failing company valued at $382,376, according to the company’s financial statements. In other words, Uzielli paid $1 million for $38,200 in equity. Bush had changed the name of Arbusto to Bush Exploration after his father became vice president. (GeeDubya says arbusto is the Spanish word for “bush,” although Cassell’s Spanish/English Dictionary translates it as “shrub,” the source of one of GeeDubya’s nicknames.) By the time of the corporate name change, Arbusto had drilled so many dry holes that West Texas oilmen called it “are-busted.” Mr. Uzielli lost his entire $1 million investment but later told reporters he didn’t regret it. He described his investment with Bush as “a losing wicket” but said “it was great fun.” What a sport.

Arbusto was not an oil company so much as it was a tax write-off company, taking advantage of the IRS tax-code provision that allowed investors to deduct up to 75 percent of their losses in the

*Maureen Dowd, columnist for The New York Times, was apparently the first journalist to use the word consigliere to describe Baker’s role in the Bush family.

oil business. Bush didn’t strike oil, he struck money from friends of his daddy. After the Uzielli bailout Bush Exploration was acquired by Spectrum 7. Spectrum 7 was owned by William DeWitt, Jr., son of the owner of the Cincinnati Reds. DeWitt couldn’t pay Bush for what remained of Bush Exploration, so he sort of took him in, made him CEO and a director, paid him $75,000 a year and $120,000 in consulting fees, and gave him 1.1 million shares of Spectrum 7 stock.

Two years later Spectrum 7 had lost $400,000 in six months and was $3 million in debt. So Harken stepped in. The Texas-based company bought Spectrum 7 for $2 million in Harken stock. Of the $2 million, $224,000 in shares went to Bush, along with options to purchase more.

There was no malfeeance [sic], nor attempt to hide anything. In the corporate world, sometimes things aren’t exactly black and white when it comes to accounting procedures.

—president george w. bush, july 8, 2002, on absence of “malfeeance” in the aloha sale

“His name was George Bush,” said Harken’s founder, Phil Kendrick. “That was worth the money they paid him.” Oil-field losses followed GeeDubya the way that cloud of dirt used to follow Pig Pen in “Peanuts.” By 1989 Harken was booking big losses but Daddy was president. In February 1990 the company’s CEO, Mikel Faulkner, warned board members that a failed deal the previous year left the company “with little cash flow flexibility.” In the months that followed, Harken’s memos and board minutes should have been written in red ink. So the management team devised a scheme to obscure these losses.

See if you can follow this bouncing ball. Harken masked its 1989 losses by selling 80 percent of a subsidiary, Aloha Petroleum, to a partnership of Harken insiders called International Marketing & Resources for $12 million. Of that sum, $11 million came from a note held by Harken. Aloha was a small chain of gas stations and convenience stores in Hawaii, originally started by J. Paul Getty and acquired by Harken in a package deal in 1986.

When Harken sold Aloha in 1989, here’s how it did the accounting. Since Harken carried an $11 million note on the $12 million sale, the only money it got up front was the first $1 million. But Harken booked $7.9 million, using the mark-to-market accounting that Enron made so fashionable in the late nineties. In January 1990, IMR in turn sold its stake in Aloha to a privately held company called Advance Petroleum Marketing, and the Harken loan was effectively transferred to Advance.

In brief, Harken insiders borrowed money from their own company to buy a subsidiary at an inflated price. Then they booked sales revenue that didn’t exist as profit. Then they got rid of the loan that had provided the revenue that never really existed. This is the kind of deal that made Enron famous. It allowed Harken to declare a modest loss of $3.3 million on its 1989 annual report, and as a result the company’s shareholders had no clue how bad things were. And we all thought the smart guys at Enron invented those clever transactions.

By 1990 Harken’s management realized that the accounting in their sale of Aloha wasn’t quite right. Their thinking on the subject had been clarified after what they described as “discussions” with the SEC. Actually, the SEC flatly declared the sale bogus. When Harken applied the standard “cost recovery” method of accounting required by the SEC, its 1988 losses suddenly became $12.57 million. It is remarkable what can be achieved by just a little attention from a federal regulatory agency. The same stan- dard accounting practices applied to 1989 showed the company had lost $3.3 million over the first three quarters, whereas the “aggressive accounting” originally applied by Harken gave them a $4.6 million profit for the period. Harken’s accounting firm was Arthur Andersen.

Any time an officer of a publicly held corporation sells stock, we ought to know within two days. We ought to know. We being shareholders and employees.

—george w. bush on wall street, july 9, 2002

Harken’s sham sale of Aloha was a shameful violation of shareholder trust, but it kept Harken’s share value up long enough to let Bush sell his stock before the corrected profit-and-loss statements were released in August. The press seemed to prefer the stock-sale story because it is easier to explain than the Aloha deal. As reporters began to press harder on the issue, even the un- flappable Ari Fleischer began to flap. “The SEC has been well aware of the issue and the SEC has concluded that this is not anything that’s actionable,” said Fleischer in early July. Bush too became testy, telling reporters that if they wanted more information they should get the minutes of Harken’s board of directors’ meetings. Harken refused to release the minutes. The story might have stalled there had it not been for the work of Charles Lewis and the Center for Public Integrity. The Washington, D.C.–based public-interest group obtained Harken board minutes and correspondence through a Freedom of Information Act request to the SEC. Then they did what both President Bush and his SEC chairman, Harvey Pitt, had refused to do: they made the documents public by putting them on the center’s website (www.publici.org).

You don’t need an accountant to interpret the Harken documents. The company was in desperate trouble. At a May 1990 meeting attended by Bush, board members discussed a stock offering they hoped would bring in enough money to keep the company solvent. Bush was named to the board’s “Fairness Committee,” which was to measure the effects of bankruptcy on small stockholders. Ever the populist, GeeDubya said at this meeting “that inherent in these principles must be the interests and preservation of value for the small shareholder of the company.” A month later Bush left the small shareholders holding the bag; he dumped $848,560 of the stock without disclosing the sale to the SEC. The purpose of the SEC’s disclosure rule is precisely to inform all shareholders that something may be wrong—by letting them know when someone with inside information sells a large block of stock.

The Harken memos show just how much Bush knew about the company’s dicey finances. By late May 1990, internal company memos warned that there was no other source of immediate financing, that a cash crunch was only days away, and that loans were slipping “out of compliance.” Banks were demanding guarantees of sufficient equity to cover the notes. As chairman of the audit committee actually working with the accounting consultants called in by the board, Bush knew exactly how grim their conclusions were. He was warned, along with other directors, in a May 25 memo that it would be illegal to dump his stock. He sold in June to a private purchaser who has never been identified.

The company was kept afloat by investments from a small liberal-arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This news was revealed only after a group of dogged and enterprising Harvard students at the nonprofit HarvardWatch dug into records there and turned their findings over to The Wall Street Journal in 2002.

Harvard’s Harken bailout helped salvage Bush’s last shaky oil company, at one time setting up a Harvard-Harken venture that moved $20 million in liabilities off Harken’s books. It also cost the university’s endowment more money than the young Bush ever earned in West Texas. Hooking up with Harken contributed to a record $200 million write-down for Harvard Management in 1991. Why did Harvard do it? Let us count the ways. Harvard Management exec Michael Eisenson sat on Harken’s board with Dubya Bush. George Herbert Walker Bush was vice president of the United States—and a Skull and Bones Yalie. His son held a Harvard Business School M.B.A.—and was a Skull and Bones Yalie. After Poppy became president and tiny Harken somehow secured a huge drilling contract in Bahrain, Harvard kept pouring millions into the little Texas oil company in ’89, ’90, and ’91.

In July 2002 the White House offered three explanations for Bush’s failure to report his own Harken stock sale. The first was that the filing of the disclosure form was “the corporation’s responsibility.” A letter from Harken’s general counsel dated October 5, 1989, gently reminds Bush that he had failed to file the same Form 4 when he exercised his director’s option to buy 25,000 shares of Harken stock exactly one year before he unloaded it in June 1990. The “Dear George” letter from Harken’s general counsel, Larry Cummings, made it clear to Bush that company lawyers or accountants couldn’t file the forms because they required his signature.

Turns out Bush regularly failed to report insider dealings to the SEC. On two occasions before his June 1990 stock dump,

Bush had sold as a board member and failed to file the disclosure forms.

There are countless subjects on which George W. Bush might have pleaded ignorance in 1990, but a failing oil business was not one of them. At the end of 1989 Harken president Mikel Faulkner told a reporter at the Petroleum Review that Harken would book more than $6 million in end-of-the-year profits. On August 22, 1990, Harken’s second-quarter report predicted $23.2 million in losses. Once the news hit the street, the stock sank immediately from $4 to $2.37; it later bottomed out at twenty-two cents a share.

Eight and a half months later The Wall Street Journal reported that the president’s son was under investigation for failure to report the stock sales. The chairman of the SEC was Richard Breeden, who had worked for Poppy Bush as an economic adviser. The walls of Breeden’s office were so plastered with photos of Poppy and Barbara Bush that a New York Times reporter observed, “George Bush is Breeden’s Mao.” The general counsel at the SEC was James Doty, the same James Doty of the Baker Botts law firm, who represented GeeDubya when he bought his 2 percent interest in the Texas Rangers with the money he got from dumping his Harken stock. The Houston law firm was founded by the great-grandfather of James Baker III, secretary of state under Bush the Elder and the point man for Bush the Younger in Florida after the disputed 2000 election.

Breeden and Doty never asked for an interview with the subject of their investigation. Since 1993 Breeden, Doty, and other partners of Baker Botts have contributed $210,621 to GeeDubya’s political campaigns, making the firm the president’s number-fourteen career patron. They were beaten out for the number-thirteen spot by Arthur Andersen, at $220,557.

In a letter regarding “George W. Bush Jr.’s [sic] Filings,” SEC investigators observed that Bush was familiar with the SEC’s filing deadlines, having met them when he filed reports of dealings with three other companies in which he owned stock. But with Harken, Bush filed “four late Forms 4 reporting four separate transactions, totaling $1,028,935.” During his first campaign for governor of Texas, Bush repeatedly told reporters he had been “exonerated” by the SEC, and Fleischer repeated the same line in the summer of ’02. But the report issued by the SEC’s enforcement division in 1993 specifically says the investigation “must in no way be construed as indicating that the party has been exonerated.”

Just as Harken was selling itself its own subsidiary in Hawaii, it set up another corporation on another island. Harken Bahrain Oil company registered in the Cayman Islands in September 1989. The Caymans, like Bermuda, are a convenient offshore address for U.S. companies that want to do business at home but prefer not to pay U.S. taxes. After the furor over tax-dodging corporations broke, Bush made this ringing statement in August 2002: “We ought to look at people who are trying to avoid U.S. taxes as a problem.” Corporate tax dodgers now cost the country seventy billion dollars annually, according to the IRS, all of which has to be made up by average citizens who can’t acquire a mail drop in the Caymans. The Scourge of Corporate Misbehavior even daringly urged corporate tax-dodgers to “pay taxes and be good citizens.” Then the White House had to acknowledge that Harken Energy had set up an offshore subsidiary to avoid taxes. Bad timing.

Harken was not Enron, but it was certainly Enron in the making. What Bush took out of Harken was also twenty times as much as Bill and Hillary Clinton lost in a crummy Arkansas real estate deal that cost American taxpayers seventy million dollars to investigate. By the time Bush signed the Corporate Responsibility Act, Harken was selling at forty-one cents a share. Don’t put your Social Security money in it.

So who are the “regular folks” who have been affected here, and what have those effects been? In this chapter, you, dear readers, are the regular folks. Americans lost $6 trillion when the stock market collapsed after Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco. It’s your 401(k) that’s the subject here, your pension, your Social Security, your investments, your savings, and your jobs. You.

Of course George W. Bush and his petty self-dealing at Harken did not cause the collapse of Enron et al. What we are looking at is not causation but connection. If one wanted to paint with a broad brush, surely Bill Clinton, president during the enormous stock market boom of the second half of the nineties, has more responsibility for the eventual collapse than does George W., president for only eighteen months when it happened.

But an even broader brush shows a different pattern. Start- ing in 1980 with the presidency of Ronald Reagan (or even the 1978 deregulation of the airlines, if you’d like to include Jimmy Carter), this country has been going through a deregulatory mania. Supply-siders, Milton Friedman, free-marketeers of all stripes, “movement conservatives,” The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page—not to mention a motley assortment of anti-government cranks from militias to Republican candidates—have been trying to persuade us that government can’t do a damn thing right and that free markets are the answer to absolutely everything. There’s a true-believerism about the free-marketeers that is genuinely unsettling, as though it were a cult or a religion in which certain fundamental assumptions are never questioned. All you have to do to believe is ignore history and experience.

Capitalism is a marvelous system for creating wealth. On the other hand, unregulated capitalism creates hideous social injustice and promptly destroys itself with greed. A marketplace needs rules. From the very beginning, capitalism has required careful regulation. In the market towns of medieval England there were as many as twenty or thirty laws governing just the balance scales, and whether you could put your thumb or any other digit on the scale. Mostly what we’ve learned from the American experiment is that competition is good, but we need rules because people cheat. And there are some natural monopolies that need regulation or they end up in cartels that rip everybody off.

Government regulation and the much-maligned trial lawyers are the two instruments by which we control corporate greed. It seems to me government is neither good nor bad but simply a tool, like a hammer. You can use a hammer to build with, or you can use a hammer to destroy with. The virtue of the hammer depends on the purposes to which it is put and the skill with which it is used.

Of course government regulation is burdensome and often absurd. One famous federal form required employers to “list your employees broken down by sex.” “None,” read one reply. “Alcohol is our problem.”

What has changed in this country over the course of the past twenty-some years is that government has served less and less as a brake on corporate behavior and more and more as a corporate auxiliary, because of the corrupting effects of the system of legalized bribery we call “campaign financing.”

And here we find the root cause of the stock market collapse. During the nineties the SEC was increasingly starved for funds by the Republican Congress on the grounds that regulation is bad, and so it suffered a tremendous erosion of its authority. While the press was telling the Enron disaster story and CEOs were stepping forward like Baptists at an altar call to restate their companies’ earnings, Bush fought for a bare-bones SEC budget, recommending $576 million in July 2002. (The House autho- rization at the time was $776 million.) Clinton’s SEC appointee, Arthur Levitt, had struggled valiantly for such obvious reforms as expensing stock options and monitoring accounting firms, but the politicians paid no attention during the years of go-go and the all-absorbing crisis over the president’s sex life.

Phil and Wendy Gramm made a significant husband-and-wife contribution to the mess. In 1992, just a few days after Bill Clinton’s election, Wendy Gramm, in her last days as the lame-duck chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Corporation (which was short two of its five members), pushed through a federal rule that exempted energy-derivatives contracts from federal regulation (because regulation is bad).* Energy derivatives were just then becoming one of Enron’s most profitable lines. According to Robert Bryce’s book on Enron, Pipe Dreams, this key piece of deregulation is what allowed Enron to become a giant in the derivatives business. The exemption not only prevented federal oversight, exempting the companies from the CFTC’s authority, it even exempted them if the contracts they were selling were designed to defraud or mislead buyers. Five weeks later Enron announced it was hiring Mrs. Gramm as a member of the Enron board, a job that eventually paid her about $1 million in salary, attendance fees, stock-option sales, and dividends. Senator Phil Gramm’s Banking Reform Act formally repealed the long-standing prohibition (which grew out of the stock crash of ’29) against merging banks, brokerage houses, and insurance companies. Then the IRS was emasculated by Gingrich Republicans on the grounds that collecting taxes is tantamount to fascism.

The whole dizzying array of corporate clout-wielders in Washington—powerful lobbyists who leave no fingerprints on curious little exemptions and special provisions that apply to only one company—gets larger and more brazen by the year.

George W. Bush didn’t invent any of this. His role is to pretty much embody it. He is what people mean when they speak of “crony capitalism.” His administration is what we mean by the cliché “setting the fox to guard the hen coop.” (Raccoons are actually far more dangerous to chickens—take our word for it.) Bush is

*The commission rule became known as the Enron exemption when it was passed into law in 2001, advanced by (Mr. Wendy) Phil Gramm, who chaired the Senate Banking Committee.

not motivated by greed—he honestly believes government should be an adjunct of corporate America and that we’ll all be better off if it is. Thus his role has been to build upon, to extend, to exaggerate, to further privatize, to cheerlead for, to evangelize about all that the free-marketeers have been preaching over the years.

The odd thing about Bush at midterm is that most of the Washington press corps has yet to recognize just how extreme his ideology is. As governor of Texas he tried to privatize the state welfare system and considered privatizing the University of Texas; he fought for “voluntary compliance” with environmental regulations. With the power of large corporations in this country already grossly disproportionate because of their influence over politicians through money, government is the last effective check on corporate greed. To put a man in charge of the government who basically doesn’t believe it should play a role is folly.

The tragedy of having him in office at this time is that the man is congenitally incapable of checking the excesses of capitalism. No sooner was the Sarbanes bill passed than Bush’s man, at the SEC Harvey Pitt, busily began undermining it. Pitt’s claim to the title of biggest raccoon in the henhouse is rivaled only by the perfectly ludicrous appointment Bush made to the board assigned to implement the new McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reforms—a man vehemently opposed to campaign-finance reform. There are contenders at Interior, Labor, and EPA as well, but Pitt probably deserves the prize. Pitt wanted to appoint Judge William Webster to head the new accounting firm oversight board set up by the Sarbanes bill. Webster turned out to have corporate conflicts of interest out the wazoo, and Pitt himself was fired as a result. However, he remained on the job and by January 2003 had managed to actually weaken the rules that had been in effect before the corporate scandals broke. So many fundamental reforms have not been addressed—the failure to count stock options as a business expense, which gives CEOs an incentive to run up stock prices with tricky accounting; out-of-control hedge funds; derivatives; directors with conflicts of interest; the list goes on. Less than nothing has been done about any of it, so one can guarantee this whole corporate-fraud fiasco is going to happen again.

George W. Bush should declare himself a conscientious objector in his own war on corporate crime.

Recenzii

“Ivins is surely one of the nation’s most adroit political commentators.” —People

“A sprightly catalogue of every destructive policy decision the Bushies have made in their first two-and-a-half years. . . . Sure to delight the president’s critics and madden his fans.” —The Washington Post Book World

“Ivins and Dubose are worthy heirs of the honorable tradition of muckraking.” —Paul Krugman, The New York Review of Books

“A thorough (and thoroughly researched) condemnation of our 43rd president's domestic policy. . . . The intensely individual stories make this much more than a tart tongue-lashing. . . . Illuminating reading.” —Austin American-Statesman U.S.

“A sprightly catalogue of every destructive policy decision the Bushies have made in their first two-and-a-half years. . . . Sure to delight the president’s critics and madden his fans.” —The Washington Post Book World

“Ivins and Dubose are worthy heirs of the honorable tradition of muckraking.” —Paul Krugman, The New York Review of Books

“A thorough (and thoroughly researched) condemnation of our 43rd president's domestic policy. . . . The intensely individual stories make this much more than a tart tongue-lashing. . . . Illuminating reading.” —Austin American-Statesman U.S.

Descriere

Ivins and Dubose take the wire brush to the Bush presidency and show how they believe he has applied the same flawed strategies he used in governing Texas to running the largest superpower in the world.