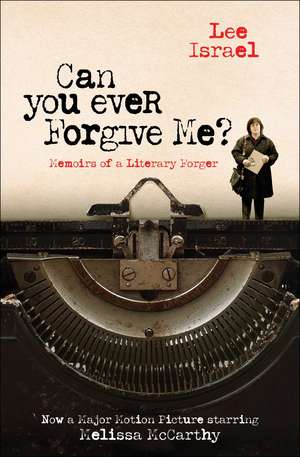

Can You Ever Forgive Me?: Memoirs of a Literary Forger

Autor Lee Israelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 9 ian 2019

Before turning to her life of crime—running a one-woman forgery business out of a phone booth in a Greenwich Village bar and even dodging the FBI—Lee Israel had a legitimate career as an author of biographies. Her first book on Tallulah Bankhead was a New York Times bestseller, and her second, on the late journalist and reporter Dorothy Kilgallen, made a splash in the headlines.

But by 1990, almost broke and desperate to hang onto her Upper West Side studio, Lee made a bold and irreversible career change: inspired by a letter she’d received once from Katharine Hepburn, and armed with her considerable skills as a researcher and celebrity biographer, she began to forge letters in the voices of literary greats. Between 1990 and 1991, she wrote more than three hundred letters in the voices of, among others, Dorothy Parker, Louise Brooks, Edna Ferber, Lillian Hellman, and Noel Coward—and sold the forgeries to memorabilia and autograph dealers.

“Lee Israel is deft, funny, and eminently entertaining…[in her] gentle parable about the modern culture of fame, about those who worship it, those who strive for it, and those who trade in its relics” (The Associated Press). Exquisitely written, with reproductions of her marvelous forgeries, Can You Ever Forgive Me? is “a slender, sordid, and pretty damned fabulous book about her misadventures” (The New York Times Book Review).

Preț: 85.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 129

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.40€ • 16.95$ • 13.65£

16.40€ • 16.95$ • 13.65£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 41.68 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982100339

ISBN-10: 1982100338

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Ediția:Media tie-in

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982100338

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Ediția:Media tie-in

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Lee Israel was the author of Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Estee Lauder: Beyond the Magic, Kilgallen, and Miss Tallulah Bankhead. She also worked as a copyeditor for Scholastic and American Express Publishing. She died in 2015.

Extras

Can You Ever Forgive Me?

I??f with that last letter you pictured the urbane playwright in Switzerland, cigarette-holdered and smoking-jacketed, dashing off a letter in the 1960s from a cozy nook high up in Chalet Coward—the house he bought in the Alps to take advantage of Switzerland’s kinda gentler tax laws—located at Les Avants, Montreux, just down the mountain from the David Nivens at Château d’Oex, where Coward entertained guests that included Marlene, Garbo, George Cukor, Rebecca West, and a group that Elaine Stritch once called “all the Dames Edith” . . . you would be wrong.

Every letter reproduced here, along with hundreds like them, were turned out by me—conceived, written, typed, and signed—in my perilously held studio apartment in the shadow of Zabar’s on New York’s Upper West Side in 1991 and 1992. A room with a view not of Alpine splendor, but of brick and pigeons, a modest flat I took in the spring of 1969 with the seventy-five-hundred-dollar advance that G. P. Putnam’s Sons had given me to do my first book, a biography of Tallulah Bankhead. I sold those letters to various autograph dealers, first in New York City, and was soon branching out across the country and abroad—for seventy-five dollars a pop.

Noël Coward’s soi-disant letters were typed by me on what I remember was a 1950ish Olympia manual, solid as a rock, bigger than a bread box, not so much portable as luggable. (Noël’s Olympia was the one I would have the most trouble schlepping when the FBI was about to come calling.) For the nonce, I was content, researching my Tallulah bio—just me, my cat, and my contract, in my cozy, rent-controlled room-with-no-view.

I had never known anything but “up” in my career, had never received even one of those formatted no-thank-you slips that successful writers look back upon with triumphant jocularity. And I regarded with pity and disdain the short-sleeved wage slaves who worked in offices. I had no reason to believe life would get anything but better. I had had no experience failing.

Miss Tallulah Bankhead was a succès d’estime. The book had respectable sales and attracted many admirers, especially in the gay community. (By which I mean men. Lesbians don’t seem to harbor the gay sensibility with the same vigorous attention to detail as the guys who, I suspect, are born with the Great American Songbook clinging to the walls of their Y chromosomes.) I continued to be wined and wooed by publishers, in various venues of young veal and Beefeater gin. My second book, Kilgallen, was conceived at one of those chic, deductible lunches, over gorgeous gin martinis. My work on the book began in the mid-1970s and continued for about four years.

I researched at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, where I was always comfortable. (I had even given the library a percentage of my take on Tallulah.) Kilgallen sold well and made the best-seller list of The New York Times. It appeared for one week with a snippy little commentary by the book-section editor, running as a kind of footer—the commentary, not the editor. Since I had written for the Arts and Leisure section frequently, when it was under the talented editorship of Seymour Peck, the paper’s distaste for my work surprised and chagrined. No matter. I was now entitled to say that I was a New York Times best-selling author, and I frequently did. A particularly compelling part of the Kilgallen story was her controversial death, which had occurred just after she told friends that she was about to reveal the truth about the assassination of JFK. I remember swimming laps, with the mantra “Who killed Dorothy? Who killed Dorothy?” playing under my swim cap. I made money from my second book. Not Kitty Kelley, beachfront-property money, and no more than I would have made in four years in middle management at a major corporation . . . as if any major corporation would have had me, or I it. There was enough, however, to keep me in restaurants and taxis.

Brick and Pigeons

I??f with that last letter you pictured the urbane playwright in Switzerland, cigarette-holdered and smoking-jacketed, dashing off a letter in the 1960s from a cozy nook high up in Chalet Coward—the house he bought in the Alps to take advantage of Switzerland’s kinda gentler tax laws—located at Les Avants, Montreux, just down the mountain from the David Nivens at Château d’Oex, where Coward entertained guests that included Marlene, Garbo, George Cukor, Rebecca West, and a group that Elaine Stritch once called “all the Dames Edith” . . . you would be wrong.

Every letter reproduced here, along with hundreds like them, were turned out by me—conceived, written, typed, and signed—in my perilously held studio apartment in the shadow of Zabar’s on New York’s Upper West Side in 1991 and 1992. A room with a view not of Alpine splendor, but of brick and pigeons, a modest flat I took in the spring of 1969 with the seventy-five-hundred-dollar advance that G. P. Putnam’s Sons had given me to do my first book, a biography of Tallulah Bankhead. I sold those letters to various autograph dealers, first in New York City, and was soon branching out across the country and abroad—for seventy-five dollars a pop.

Noël Coward’s soi-disant letters were typed by me on what I remember was a 1950ish Olympia manual, solid as a rock, bigger than a bread box, not so much portable as luggable. (Noël’s Olympia was the one I would have the most trouble schlepping when the FBI was about to come calling.) For the nonce, I was content, researching my Tallulah bio—just me, my cat, and my contract, in my cozy, rent-controlled room-with-no-view.

I had never known anything but “up” in my career, had never received even one of those formatted no-thank-you slips that successful writers look back upon with triumphant jocularity. And I regarded with pity and disdain the short-sleeved wage slaves who worked in offices. I had no reason to believe life would get anything but better. I had had no experience failing.

Miss Tallulah Bankhead was a succès d’estime. The book had respectable sales and attracted many admirers, especially in the gay community. (By which I mean men. Lesbians don’t seem to harbor the gay sensibility with the same vigorous attention to detail as the guys who, I suspect, are born with the Great American Songbook clinging to the walls of their Y chromosomes.) I continued to be wined and wooed by publishers, in various venues of young veal and Beefeater gin. My second book, Kilgallen, was conceived at one of those chic, deductible lunches, over gorgeous gin martinis. My work on the book began in the mid-1970s and continued for about four years.

I researched at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, where I was always comfortable. (I had even given the library a percentage of my take on Tallulah.) Kilgallen sold well and made the best-seller list of The New York Times. It appeared for one week with a snippy little commentary by the book-section editor, running as a kind of footer—the commentary, not the editor. Since I had written for the Arts and Leisure section frequently, when it was under the talented editorship of Seymour Peck, the paper’s distaste for my work surprised and chagrined. No matter. I was now entitled to say that I was a New York Times best-selling author, and I frequently did. A particularly compelling part of the Kilgallen story was her controversial death, which had occurred just after she told friends that she was about to reveal the truth about the assassination of JFK. I remember swimming laps, with the mantra “Who killed Dorothy? Who killed Dorothy?” playing under my swim cap. I made money from my second book. Not Kitty Kelley, beachfront-property money, and no more than I would have made in four years in middle management at a major corporation . . . as if any major corporation would have had me, or I it. There was enough, however, to keep me in restaurants and taxis.

Recenzii

"Israel displayed an excellent ear and fine false turn of phrase...Now, all these years later, she's written a slender, sordid and pretty damned fabulous book about her misadventures...There's no honor in anything she did, but after reading Can You Ever Forgive Me? it's hard to resist admitting Israel to the company of such sharp, gallant characters as Dawn Powell and Helene Hanff, women clinging to New York literary life, or its fringes, by their talented fingernails." —Thomas Mallon, The New York Times Book Review

"Lee Israel is deft, funny and eminently entertaining...She also has a good tale to tell. Can You Ever Forgive Me? offers a gentle parable about the modern culture of fame, about those who worship it, those w ho strive for it and those who trade in its relics." —Jonathan Lopez, The Associated Press

"With her witty, jeweled prose and her troubling antics, literary outlaw and minx Lee Israel is once again causing a ruckus. Do I trust her and her admission of guilt? Do I condone her actions? I'm loving the experience of trying to answer these questions." —Henry Alford, investigative humorist, author of Big Kiss, Municipal Bondage, and contributing editor to Vanity Fair

"Whether she's writing about being banned from the Strand bookstore or stealing authentic letters from university libraries, she does so with honesty and a rapier wit. And in an age of promiscuous apology for the slightest wrongdoing, the fact that Israel never fully apologizes for her crimes is actually part of the charm of her memoir." —VeryShortList

"Lee Israel is deft, funny and eminently entertaining...She also has a good tale to tell. Can You Ever Forgive Me? offers a gentle parable about the modern culture of fame, about those who worship it, those w ho strive for it and those who trade in its relics." —Jonathan Lopez, The Associated Press

"With her witty, jeweled prose and her troubling antics, literary outlaw and minx Lee Israel is once again causing a ruckus. Do I trust her and her admission of guilt? Do I condone her actions? I'm loving the experience of trying to answer these questions." —Henry Alford, investigative humorist, author of Big Kiss, Municipal Bondage, and contributing editor to Vanity Fair

"Whether she's writing about being banned from the Strand bookstore or stealing authentic letters from university libraries, she does so with honesty and a rapier wit. And in an age of promiscuous apology for the slightest wrongdoing, the fact that Israel never fully apologizes for her crimes is actually part of the charm of her memoir." —VeryShortList