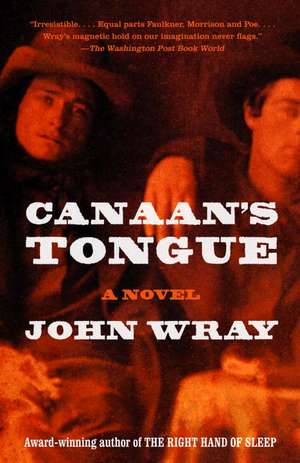

Canaan's Tongue

Autor John Wrayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2006

Thaddeus Morelle’s followers call him “the Redeemer.” Over the years he has led the Island 37 Gang from stealing horses to stealing slaves in an enterprise so nefarious that both the Union and Confederacy have placed a bounty on their heads. But now Morelle is dead, murdered by his puppet and prot?g?, Virgil Ball, who may rid himself of the Redeemer but can never be free of his Trade. Based on the true story of John Murrell, a figure once as infamous as Jesse James, Canaan’s Tongue is suspenseful and fiercely comic, a modern masterpiece of the American grotesque.

Preț: 82.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.86€ • 16.35$ • 13.39£

15.86€ • 16.35$ • 13.39£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400033812

ISBN-10: 1400033810

Pagini: 341

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400033810

Pagini: 341

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

John Wray was born in Washington, D.C., and has since lived in Texas, Alaska, Chile, and New York. His first novel, The Right Hand of Sleep, was a New York Times Notable Book and a Los Angeles Times Best Book of the Year. Wray is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award. He currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Extras

HORSE - THIEVERY.

It began at a respectable camp-meeting, Virgil says.

I first laid eyes on the Redeemer in May of ’51, just upriver from Natchez. I was passing the head of Lafitte's Chute in a pine-sap canoe I'd paid for honestly in Vicksburg when the immaculate white of a revival tent caught my notice, fluttering bravely at a spot that had been wilderness only a fortnight before. I banked my canoe in the shade and climbed up the muddy, stump-littered slope, aiming to satisfy my curiosity at the tent-flap. A water-stained bill stuck to the canvas by what looked to be a lady's hatpin caught my eye–:

THADDEUS H. MUREL

REDEEMER OF LAMBS

"The Same Came For A Witness;

To Bear Witness Of The Light"

On the far side of the tent, past a cluster of traps and wagons, thirty-odd horses stood tethered in a row. There were a few skiffs and bucket-boats farther up the bank, but not many. Most of the congregation looked to have come on foot. Up close, the canvas was frayed and weathered–: peering in through a thumb-sized gash, I saw the tent was amply filled with lambs. I hung back a moment, overcome by a fit of bashfulness (I was a rather timid vagrant in those days) and looked straight above me at the sky. It was sapphire blue, I remember, and wonderfully calm. A warbling rose up now and then inside the tent, punctuating the reedy exhortations of the preacher. Even through the heavy cloth his voice had something queer about it, something out of place, as though a chimpanzee were lecturing a learned assembly. My prudence did battle with my curiosity, fired a brave volley, and collapsed in a heap of dust. I parted the tent-flap and slipped inside.

In doing so I sentenced my Christian self to death, though at the time I felt nothing but astonishment. Through a breach in the crowd I saw the preacher on his crate pulpit, gasping and spitting and proselytizing and weeping–: a delicate, sallow-faced, limp-haired dwarf, in a suit that looked cut out of butcher's paper. I mumbled an oath and passed a hand over my eyes. Was this some manner of vaudeville? Had I mistaken a curiosity-show for a bonafide camp meeting? I stood stock-still for a spell, my right hand clutching at the tentflap, my left hand in front of me, as if in expectation of a fall. Then I found a place for myself at the back of the airless, man-smelling tent and listened.

The preacher wore a bicornered hat of brushed black silk, the kind Napoleon favored at Waterloo. His left fore-finger rested lightly on a bible, and he was declaiming in a tremulous voice, a voice riddled with earthly suffering–:

Truly God is good to Israel, even to such as are clean of heart. But as for me, my feet were almost gone; my steps had well-nigh slipped. For I was envious at the foolish, when I saw the prosperity of the wicked.

He paused the briefest of instants and raised his rum-colored eyeballs to survey us. I'd been to revivals before, and was used to their choked-back burlesqueries–; delighted in them, in fact. This was altogether different. The few women in the crowd clutched at their bosoms and wept in silent misery–; the men stood together in a clot, staring at the preacher with a look of unleavened murder. They did their best to drive the notion from their minds, of course, as the killing of a preacher is no small matter in the eyes of God and society. But the urge was there, and unquiet–: you could read it in their faces. And it was this very same urge held them in his power.

For there are no bands in their Death, the preacher continued, lingering affectionately over his t's and s's in an unmistakable shanty-town lisp. I smiled a little to myself–: this sport of nature had come–of all places!–from the nigger-townships down along the delta. But he was all the more marvellous for it.

They are not in trouble as other men: neither are they plagued like other men. Therefore pride compaseth them about as a chain; violence covereth them as a garment…

He leaned slowly forward, the trace of a frown on his damp, rat-like face, and glanced up from the book as though he'd just recollected us. “This puts me in mind of an episode from my own life,” he said in a wistful voice. Planting a finger on the little book, as if to keep it from escaping, he began–:

“I was raised on an acre of black peat in Virginia, youngest boy to a simple, scripture-loving planter of plug tobacco. There were thirteen of us all told, minnowed into two eight-by-seven-foot rooms. But we lived modestly, and praised God nightly in our prayers.” The crate creaked angrily beneath his feet. “Up the lane lived a great patriarch, Yeoman Dorne, with his wife and seven sons. The youngest of them, Ezekiel, was my equal in years.”

His eyes grew melancholy and fixed. “Lord knows, our lot was not a disburthened one,” he said.

Sundry matrons let out anticipatory sighs.

“Hejekuma Morelle, my grandfather,” said the preacher, “was, to put not too fine a point on it, stricken with the pox.” (assorted gasps and mutterings.) “Contrary-wise, Yeoman Dorne–a Bostoner–was a wide-breasted squire of sixty-five, arresting in person and boisterous in manner. The cries and frequent imprecations to our Lord by my grandfather, who raved and cursed us in his misery, took their toll not only on my grandmother, Odette – who developed in consequence a nervous palsy – but also on my mother, Anne-Marie, who grew progressively weaker from lack of sleep, and presented an easy mark to the cholera which swept through the country in the winter of Twenty-nine.” (Brighter, more plaintive whimperings from the choir.) “Morelia Dorne, wife of our neighbor, whose boots we buffed, whose wheat we threshed, never suffered the least complaint of health and bore seven healthy, plum-cheeked boys.”

The preacher regarded the assembly dolefully. Not a word was spoken during that very lengthy pause. The breeze rustled the canvas and moved the tent-poles from side to side, giving the illusion of a ship at sea, or at least of a barge in a heavy current. Finally he cleared his throat.

“The premature end of my sweet mother sent my father, who'd never been entirely right in the head, into antics of filth and violence undreamt-of by Christian man. My eldest brother, Thaddeus Everett–whose left side was withered from birth–made the error of reprimanding my father one evening for his profligacy, calling on saints Peter and Albert as his witnesses. My father brained him with a cast-iron chimney pan.” The preacher paused again. “The sight of that drove my sister, Sophia, clean out of her wits, and troubled all of our sleep for six months thereafter. My grandfather's blubberings, needless to say, continued without abatement.”

The preacher had not so much as blinked since the commencement of his narrative. His face was placid as a saint’s. Ignoring the mounting disbelief of the crowd, he continued–: “The eldest Dorne boy, Patríce, excelled at hunting, fishing and the steeple-chase, in which last he took particular pleasure on account of the Libyan thorough-bred with which his father had lately furnished him. Contrary-wise, my second sister Margaret, a bed-ridden cripple, witnessed the unrelenting recession of our family's fortunes stoically from her pallet by the coke-stove. My younger brother, Thaddeus Benjamin, had the skin slowly peeled from his body for the sole offence of stuttering at the supper-table–; Ezekiel, my counterpart in the Dorne household, was never, to my knowledge, so much as shat on by a pigeon. My third sister, Isabel, was set upon, while still quite young, by a hungry sow and horribly disfigured. Each of the Dorne boys, contrary-wise, received a trained jacarundi at their confirmation, with a pearl-and-moleskin collar on which the Declaration of Independence, in its entirety, had been embroidered in platinum thread. Esperanza, our youngest, was seized by my grandfather in a fit of syphilitic delirium, taken hold of by the ears, and repeatedly, mercilessly–“

At this instant the preacher's litany was cut short by the sobs of a woman to the left of the pulpit.

With a wink to the assembled crowd, he turned to her.

“You there,” he said. “You, little mother! Would you venture to affirm that you know your scripture?”

I could just make out the back of the woman's head, if I stood on tip-toe. It shook a little, but she answered confidently enough–:

“I believe I do, preacher.”

“We'll see what you believe,” the preacher said. His voice was low and reverent. Holding his right hand aloft, he intoned–:

Their eyes stand out with fatness: They have more than heart could wish.

“Who is being discussed here?” he asked, looking not at the woman but over her black-bonnetted head at the rest of us. A light was beginning to kindle in his eyes.

“The wicked,” the woman answered promptly.

“The wicked,” the preacher repeated for our benefit. He coughed once into his sleeve. “Recognize them, do you, from that description?”

“I haven't–beg pardon, I recognize their manner from it,” the woman said. “I'd know them by their ways, sir, yes.”

“Your familiarity, sister, with the ways and manners of the wicked is duly noted,” the preacher said. A ripple of laughter ran through the tent. “Pray continue your declamation for us.”

The woman said nothing, shaking her head more resolutely now.

“No?” said the preacher, frowning. “Nothing? Shall we give you more? Good–; we'll give you more.” He ran his finger slowly, almost coquettishly, down the page.

They are corrupt, and speak wickedly concerning oppression: They speak loftily.

He paused again. The tent was as silent, in that moment, as a genuine church might have been. The woman was one of a small, severely clothed handful at the very front who looked to be the only persons there to have opened the Holy Book–; the others, by the look of them, were in the habit of passing their sabbath-days in decidedly looser collars. The preacher smiled at us and shifted his balance on the crate.

“I don't follow, sir,” the woman said, looking to either side of her in perplexity. “I don't see that I warrant–“

“They set their mouths against the Heavens,” the preacher hissed, glaring down at her as though the Antichrist were hidden in her bonnet–: “They set their mouths against the heavens, and-their-tongue-walketh-through-the-earth. There! What is the lesson in that, little mother-in-Jesus?” He stepped–or rather teetered–back from the edge of the crate as he spoke, holding the small glossy book above him like a tomahawk. I saw now that it was a cheap brush-peddler's copy, the sort passed out at every river-landing. “Their tongue WALKETH through the earth,” he sang out, slapping the binding smartly with his palm. “Psalm Seventy-three, One nine!”

The woman made no attempt at a reply. The bonnet hid her face from us, but it was plain that she was weeping. The preacher looked down at her contentedly. He was a puzzle to us all, and an entertainment–; but he was more than that. He was a revelation.

“Their tongue walketh through the earth,” he said once more, almost too quietly to hear.

Just then a scuffling began outside the tent. No-one else seemed to take note of it, though the sound was irregular and close. Perhaps the preacher did, however, as he suddenly stood bolt upright and sucked in a solemn breath. In spite of his exceeding smallness–or perhaps because of it–this act had a tragic nobility that was irresistible. It seemed as if he were about to embark, with gentility and grace, upon a long and sweetly rendered discourse on human suffering.

Instead he hurled himself down at the stricken woman, buffeting the air with the little book, his thin voice sharpening to a shriek–:

“It’s ME, of course, little mother-in-Jesus! Me! Can’t you find me in that scrap of doggerel? Can’t you make out my silhouette? Do my eyes not stand out with fatness? Does pride not compass me about? Have I not set my mouth against the Heavens? Answer! Have I not spoken loftily?”

He tossed the book aside and caught the woman about the waist, pulling a pocket-mirror from his coat and bringing it within a hair's-breadth of her face–:

“The lesson, little mother, is not to go rooting about for sweet-meats when your bowels were meant for oats.”

The woman’s body slumped forward slightly, as though the wind had gone out of it. She put up no resistance. The preacher’s next words came out very like a hymn–:

Look upon your cud-chewing nature, blessed of Jahweh, and be content.

The image of him in that instant is graven onto my memory like acid onto copper plate. He stood stock-still before the woman, one arm hidden among the starched pleats of her dress, the other holding the mirror aloft that the entire tent might peer into it. He was a good deal smaller than his victim and there was something about him of the supplicant and the schoolboy even as he stared up into her eyes, his face a patch-work of malice, exhultation and Heaven knows what species of desire. The rest of the women buried their faces in their shawls–; the men howled at the pulpit like heifers at a branding.

No-one had made a move as yet, however. All stood looking on abjectly, stiffly, breaking away in a great show of disgust only to look back at once, helpless as babes in their curiosity. Some of the men had begun, without being aware of it themselves, to leer. The sermon had done its work–: in the space of five minutes the assembly under the tent–which at first had borne at least a skin-deep resemblance to a gathering of the faithful–had been exposed as a carnival of mawkishness and lust. A dream-like stillness overcame me, the stillness of astonishment, weighing down my awareness and my limbs–; I turned back sleepily to face the pulpit. The preacher was now clutching the woman's head by its tight, revivalist bun and fumbling with the fly-button of his britches.

In the blink of an eye the crowd swung shut on them like a gate. I fought my way forward with all my strength–; just as I reached the pulpit, however, shouts rang out behind me and the gate swung open as inexorably as it had closed. The preacher and his catechist had vanished. A tide of bewildered faces swept me out onto the grass–: it was the better part of a minute before I was able to get my bearings. When at last I did, I couldn't suppress a laugh–: along the edge of the tent lay a row of cast-off saddles, ranged neatly side-by-side in the weeds. Of the thirty-odd horses there was not a trace.

Neither, when I made my way back inside, was there any sign of the ‘Redeemer’. A throng of bloodless-looking men stood packed together at the pulpit, cursing and whispering to one another–; it was impossible to guess whether he'd escaped or been bustled off to the nearest fork-limbed tree. A deep and righteous violence prevailed. A number of suspicious looks were directed toward me, on account of my ragged river-clothes–: I came to my senses, turned my back on the lot of them and slunk quietly back to my skiff. Only when I was well out on the water did I notice the thick, oily throbbing of my brain, as though I’d spent the last hour drinking mash.

From the Hardcover edition.

It began at a respectable camp-meeting, Virgil says.

I first laid eyes on the Redeemer in May of ’51, just upriver from Natchez. I was passing the head of Lafitte's Chute in a pine-sap canoe I'd paid for honestly in Vicksburg when the immaculate white of a revival tent caught my notice, fluttering bravely at a spot that had been wilderness only a fortnight before. I banked my canoe in the shade and climbed up the muddy, stump-littered slope, aiming to satisfy my curiosity at the tent-flap. A water-stained bill stuck to the canvas by what looked to be a lady's hatpin caught my eye–:

THADDEUS H. MUREL

REDEEMER OF LAMBS

"The Same Came For A Witness;

To Bear Witness Of The Light"

On the far side of the tent, past a cluster of traps and wagons, thirty-odd horses stood tethered in a row. There were a few skiffs and bucket-boats farther up the bank, but not many. Most of the congregation looked to have come on foot. Up close, the canvas was frayed and weathered–: peering in through a thumb-sized gash, I saw the tent was amply filled with lambs. I hung back a moment, overcome by a fit of bashfulness (I was a rather timid vagrant in those days) and looked straight above me at the sky. It was sapphire blue, I remember, and wonderfully calm. A warbling rose up now and then inside the tent, punctuating the reedy exhortations of the preacher. Even through the heavy cloth his voice had something queer about it, something out of place, as though a chimpanzee were lecturing a learned assembly. My prudence did battle with my curiosity, fired a brave volley, and collapsed in a heap of dust. I parted the tent-flap and slipped inside.

In doing so I sentenced my Christian self to death, though at the time I felt nothing but astonishment. Through a breach in the crowd I saw the preacher on his crate pulpit, gasping and spitting and proselytizing and weeping–: a delicate, sallow-faced, limp-haired dwarf, in a suit that looked cut out of butcher's paper. I mumbled an oath and passed a hand over my eyes. Was this some manner of vaudeville? Had I mistaken a curiosity-show for a bonafide camp meeting? I stood stock-still for a spell, my right hand clutching at the tentflap, my left hand in front of me, as if in expectation of a fall. Then I found a place for myself at the back of the airless, man-smelling tent and listened.

The preacher wore a bicornered hat of brushed black silk, the kind Napoleon favored at Waterloo. His left fore-finger rested lightly on a bible, and he was declaiming in a tremulous voice, a voice riddled with earthly suffering–:

Truly God is good to Israel, even to such as are clean of heart. But as for me, my feet were almost gone; my steps had well-nigh slipped. For I was envious at the foolish, when I saw the prosperity of the wicked.

He paused the briefest of instants and raised his rum-colored eyeballs to survey us. I'd been to revivals before, and was used to their choked-back burlesqueries–; delighted in them, in fact. This was altogether different. The few women in the crowd clutched at their bosoms and wept in silent misery–; the men stood together in a clot, staring at the preacher with a look of unleavened murder. They did their best to drive the notion from their minds, of course, as the killing of a preacher is no small matter in the eyes of God and society. But the urge was there, and unquiet–: you could read it in their faces. And it was this very same urge held them in his power.

For there are no bands in their Death, the preacher continued, lingering affectionately over his t's and s's in an unmistakable shanty-town lisp. I smiled a little to myself–: this sport of nature had come–of all places!–from the nigger-townships down along the delta. But he was all the more marvellous for it.

They are not in trouble as other men: neither are they plagued like other men. Therefore pride compaseth them about as a chain; violence covereth them as a garment…

He leaned slowly forward, the trace of a frown on his damp, rat-like face, and glanced up from the book as though he'd just recollected us. “This puts me in mind of an episode from my own life,” he said in a wistful voice. Planting a finger on the little book, as if to keep it from escaping, he began–:

“I was raised on an acre of black peat in Virginia, youngest boy to a simple, scripture-loving planter of plug tobacco. There were thirteen of us all told, minnowed into two eight-by-seven-foot rooms. But we lived modestly, and praised God nightly in our prayers.” The crate creaked angrily beneath his feet. “Up the lane lived a great patriarch, Yeoman Dorne, with his wife and seven sons. The youngest of them, Ezekiel, was my equal in years.”

His eyes grew melancholy and fixed. “Lord knows, our lot was not a disburthened one,” he said.

Sundry matrons let out anticipatory sighs.

“Hejekuma Morelle, my grandfather,” said the preacher, “was, to put not too fine a point on it, stricken with the pox.” (assorted gasps and mutterings.) “Contrary-wise, Yeoman Dorne–a Bostoner–was a wide-breasted squire of sixty-five, arresting in person and boisterous in manner. The cries and frequent imprecations to our Lord by my grandfather, who raved and cursed us in his misery, took their toll not only on my grandmother, Odette – who developed in consequence a nervous palsy – but also on my mother, Anne-Marie, who grew progressively weaker from lack of sleep, and presented an easy mark to the cholera which swept through the country in the winter of Twenty-nine.” (Brighter, more plaintive whimperings from the choir.) “Morelia Dorne, wife of our neighbor, whose boots we buffed, whose wheat we threshed, never suffered the least complaint of health and bore seven healthy, plum-cheeked boys.”

The preacher regarded the assembly dolefully. Not a word was spoken during that very lengthy pause. The breeze rustled the canvas and moved the tent-poles from side to side, giving the illusion of a ship at sea, or at least of a barge in a heavy current. Finally he cleared his throat.

“The premature end of my sweet mother sent my father, who'd never been entirely right in the head, into antics of filth and violence undreamt-of by Christian man. My eldest brother, Thaddeus Everett–whose left side was withered from birth–made the error of reprimanding my father one evening for his profligacy, calling on saints Peter and Albert as his witnesses. My father brained him with a cast-iron chimney pan.” The preacher paused again. “The sight of that drove my sister, Sophia, clean out of her wits, and troubled all of our sleep for six months thereafter. My grandfather's blubberings, needless to say, continued without abatement.”

The preacher had not so much as blinked since the commencement of his narrative. His face was placid as a saint’s. Ignoring the mounting disbelief of the crowd, he continued–: “The eldest Dorne boy, Patríce, excelled at hunting, fishing and the steeple-chase, in which last he took particular pleasure on account of the Libyan thorough-bred with which his father had lately furnished him. Contrary-wise, my second sister Margaret, a bed-ridden cripple, witnessed the unrelenting recession of our family's fortunes stoically from her pallet by the coke-stove. My younger brother, Thaddeus Benjamin, had the skin slowly peeled from his body for the sole offence of stuttering at the supper-table–; Ezekiel, my counterpart in the Dorne household, was never, to my knowledge, so much as shat on by a pigeon. My third sister, Isabel, was set upon, while still quite young, by a hungry sow and horribly disfigured. Each of the Dorne boys, contrary-wise, received a trained jacarundi at their confirmation, with a pearl-and-moleskin collar on which the Declaration of Independence, in its entirety, had been embroidered in platinum thread. Esperanza, our youngest, was seized by my grandfather in a fit of syphilitic delirium, taken hold of by the ears, and repeatedly, mercilessly–“

At this instant the preacher's litany was cut short by the sobs of a woman to the left of the pulpit.

With a wink to the assembled crowd, he turned to her.

“You there,” he said. “You, little mother! Would you venture to affirm that you know your scripture?”

I could just make out the back of the woman's head, if I stood on tip-toe. It shook a little, but she answered confidently enough–:

“I believe I do, preacher.”

“We'll see what you believe,” the preacher said. His voice was low and reverent. Holding his right hand aloft, he intoned–:

Their eyes stand out with fatness: They have more than heart could wish.

“Who is being discussed here?” he asked, looking not at the woman but over her black-bonnetted head at the rest of us. A light was beginning to kindle in his eyes.

“The wicked,” the woman answered promptly.

“The wicked,” the preacher repeated for our benefit. He coughed once into his sleeve. “Recognize them, do you, from that description?”

“I haven't–beg pardon, I recognize their manner from it,” the woman said. “I'd know them by their ways, sir, yes.”

“Your familiarity, sister, with the ways and manners of the wicked is duly noted,” the preacher said. A ripple of laughter ran through the tent. “Pray continue your declamation for us.”

The woman said nothing, shaking her head more resolutely now.

“No?” said the preacher, frowning. “Nothing? Shall we give you more? Good–; we'll give you more.” He ran his finger slowly, almost coquettishly, down the page.

They are corrupt, and speak wickedly concerning oppression: They speak loftily.

He paused again. The tent was as silent, in that moment, as a genuine church might have been. The woman was one of a small, severely clothed handful at the very front who looked to be the only persons there to have opened the Holy Book–; the others, by the look of them, were in the habit of passing their sabbath-days in decidedly looser collars. The preacher smiled at us and shifted his balance on the crate.

“I don't follow, sir,” the woman said, looking to either side of her in perplexity. “I don't see that I warrant–“

“They set their mouths against the Heavens,” the preacher hissed, glaring down at her as though the Antichrist were hidden in her bonnet–: “They set their mouths against the heavens, and-their-tongue-walketh-through-the-earth. There! What is the lesson in that, little mother-in-Jesus?” He stepped–or rather teetered–back from the edge of the crate as he spoke, holding the small glossy book above him like a tomahawk. I saw now that it was a cheap brush-peddler's copy, the sort passed out at every river-landing. “Their tongue WALKETH through the earth,” he sang out, slapping the binding smartly with his palm. “Psalm Seventy-three, One nine!”

The woman made no attempt at a reply. The bonnet hid her face from us, but it was plain that she was weeping. The preacher looked down at her contentedly. He was a puzzle to us all, and an entertainment–; but he was more than that. He was a revelation.

“Their tongue walketh through the earth,” he said once more, almost too quietly to hear.

Just then a scuffling began outside the tent. No-one else seemed to take note of it, though the sound was irregular and close. Perhaps the preacher did, however, as he suddenly stood bolt upright and sucked in a solemn breath. In spite of his exceeding smallness–or perhaps because of it–this act had a tragic nobility that was irresistible. It seemed as if he were about to embark, with gentility and grace, upon a long and sweetly rendered discourse on human suffering.

Instead he hurled himself down at the stricken woman, buffeting the air with the little book, his thin voice sharpening to a shriek–:

“It’s ME, of course, little mother-in-Jesus! Me! Can’t you find me in that scrap of doggerel? Can’t you make out my silhouette? Do my eyes not stand out with fatness? Does pride not compass me about? Have I not set my mouth against the Heavens? Answer! Have I not spoken loftily?”

He tossed the book aside and caught the woman about the waist, pulling a pocket-mirror from his coat and bringing it within a hair's-breadth of her face–:

“The lesson, little mother, is not to go rooting about for sweet-meats when your bowels were meant for oats.”

The woman’s body slumped forward slightly, as though the wind had gone out of it. She put up no resistance. The preacher’s next words came out very like a hymn–:

Look upon your cud-chewing nature, blessed of Jahweh, and be content.

The image of him in that instant is graven onto my memory like acid onto copper plate. He stood stock-still before the woman, one arm hidden among the starched pleats of her dress, the other holding the mirror aloft that the entire tent might peer into it. He was a good deal smaller than his victim and there was something about him of the supplicant and the schoolboy even as he stared up into her eyes, his face a patch-work of malice, exhultation and Heaven knows what species of desire. The rest of the women buried their faces in their shawls–; the men howled at the pulpit like heifers at a branding.

No-one had made a move as yet, however. All stood looking on abjectly, stiffly, breaking away in a great show of disgust only to look back at once, helpless as babes in their curiosity. Some of the men had begun, without being aware of it themselves, to leer. The sermon had done its work–: in the space of five minutes the assembly under the tent–which at first had borne at least a skin-deep resemblance to a gathering of the faithful–had been exposed as a carnival of mawkishness and lust. A dream-like stillness overcame me, the stillness of astonishment, weighing down my awareness and my limbs–; I turned back sleepily to face the pulpit. The preacher was now clutching the woman's head by its tight, revivalist bun and fumbling with the fly-button of his britches.

In the blink of an eye the crowd swung shut on them like a gate. I fought my way forward with all my strength–; just as I reached the pulpit, however, shouts rang out behind me and the gate swung open as inexorably as it had closed. The preacher and his catechist had vanished. A tide of bewildered faces swept me out onto the grass–: it was the better part of a minute before I was able to get my bearings. When at last I did, I couldn't suppress a laugh–: along the edge of the tent lay a row of cast-off saddles, ranged neatly side-by-side in the weeds. Of the thirty-odd horses there was not a trace.

Neither, when I made my way back inside, was there any sign of the ‘Redeemer’. A throng of bloodless-looking men stood packed together at the pulpit, cursing and whispering to one another–; it was impossible to guess whether he'd escaped or been bustled off to the nearest fork-limbed tree. A deep and righteous violence prevailed. A number of suspicious looks were directed toward me, on account of my ragged river-clothes–: I came to my senses, turned my back on the lot of them and slunk quietly back to my skiff. Only when I was well out on the water did I notice the thick, oily throbbing of my brain, as though I’d spent the last hour drinking mash.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"There is wild, wicked music throughout these pages." –Sam Lipsyte, New York Times Book Review“Richly atmospheric. . . . To read Canaan’s Tongue is to be wholly enveloped in its dark world.” –The Times-Picayune“This novel is an achievement, easily one of the best by a young American to appear this year.” –The New York Sun“Filled with vain, gorgeous language, mystical illustrations and merciless schemes. . . . It is as if Mark Twain wrote an episode of Deadwood set on the Mississippi.” –The New York Times"Irresistible, equal parts Faulkner, Morrison and Poe. . . . Wray's magnetic hold on our imagination never flags." –Ron Charles, Washington Post Book World"Wray is the real thing, and Canaan's Tongue is itself a masterpiece. . . . Somewhat resembles–and arguably surpasses in richness and color–Cormac McCarthy's Blood Meridian."–Kirkus (starred review)"Wray is tapping into essential aspects of American history and culture. . . . Canaan's Tongue reveals boldly and mythically, as few other novels have done, the hallucinatory conjunction of conquest, religious fervor, patriotic gore and the relentless striving for profit that have characterized America from its beginnings to the first decade of the 21st Century." –Frederic Koeppel, Memphis Commercial Appeal"Pure Southern gothic . . . Reads like dark poetry" –Dallas Morning News"John Wray's novel is an achievement, easily one of the best by a young American to appear this year." –New York Sun"The dark side of American history has always been best treated by the novel, and Wray does justice to some incredibly rich and challenging material, forging a style that is as loose and wild as its subjects."–Publishers Weekly (starred review)"An ambitious and strongly allegorical tale about the ability of belief to structure reality."–Library Journal"A powerfully dark story that incorporates Southern culture and the wisdom of the kabbalah with just a touch of the occult."–Booklist

Descriere

In a crumbling estate on the banks of the Mississippi, eight survivors of the nortorious Island 37 Gang wait for the war, or the Pinkerton Detective Agency, to claim them. Their leader, a bizarre charismatic known only as "The Redeemer," has disappeared without a trace, and they are wanted by both the Union and the Confederacy.