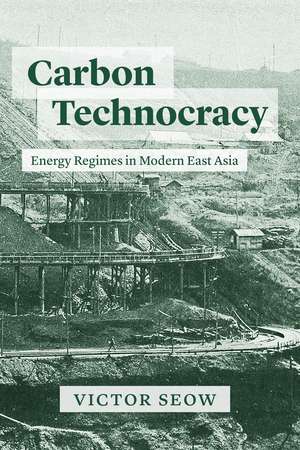

Carbon Technocracy: Energy Regimes in Modern East Asia: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute

Autor Victor Seowen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 mai 2023

The coal-mining town of Fushun in China’s Northeast is home to a monstrous open pit. First excavated in the early twentieth century, this pit grew like a widening maw over the ensuing decades, as various Chinese and Japanese states endeavored to unearth Fushun’s purportedly “inexhaustible” carbon resources. Today, the depleted mine that remains is a wondrous and terrifying monument to fantasies of a fossil-fueled future and the technologies mobilized in attempts to turn those developmentalist dreams into reality.

In Carbon Technocracy, Victor Seow uses the remarkable story of the Fushun colliery to chart how the fossil fuel economy emerged in tandem with the rise of the modern technocratic state. Taking coal as an essential feedstock of national wealth and power, Chinese and Japanese bureaucrats, engineers, and industrialists deployed new technologies like open-pit mining and hydraulic stowage in pursuit of intensive energy extraction. But as much as these mine operators idealized the might of fossil fuel–driven machines, their extractive efforts nevertheless relied heavily on the human labor that those devices were expected to displace. Under the carbon energy regime, countless workers here and elsewhere would be subjected to invasive techniques of labor control, ever-escalating output targets, and the dangers of an increasingly exploited earth.

Although Fushun is no longer the coal capital it once was, the pattern of aggressive fossil-fueled development that led to its ascent endures. As we confront a planetary crisis precipitated by our extravagant consumption of carbon, it holds urgent lessons. This is a groundbreaking exploration of how the mutual production of energy and power came to define industrial modernity and the wider world that carbon made.

Din seria Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute

-

Preț: 267.74 lei

Preț: 267.74 lei -

Preț: 160.40 lei

Preț: 160.40 lei -

Preț: 267.31 lei

Preț: 267.31 lei -

Preț: 212.43 lei

Preț: 212.43 lei -

Preț: 239.61 lei

Preț: 239.61 lei -

Preț: 211.83 lei

Preț: 211.83 lei - 23%

Preț: 507.74 lei

Preț: 507.74 lei -

Preț: 210.70 lei

Preț: 210.70 lei -

Preț: 518.09 lei

Preț: 518.09 lei - 19%

Preț: 645.98 lei

Preț: 645.98 lei - 19%

Preț: 446.01 lei

Preț: 446.01 lei - 19%

Preț: 505.45 lei

Preț: 505.45 lei - 5%

Preț: 214.33 lei

Preț: 214.33 lei - 19%

Preț: 567.04 lei

Preț: 567.04 lei - 46%

Preț: 116.77 lei

Preț: 116.77 lei -

Preț: 142.85 lei

Preț: 142.85 lei - 7%

Preț: 323.97 lei

Preț: 323.97 lei - 14%

Preț: 457.41 lei

Preț: 457.41 lei - 17%

Preț: 154.26 lei

Preț: 154.26 lei - 23%

Preț: 571.41 lei

Preț: 571.41 lei - 21%

Preț: 257.40 lei

Preț: 257.40 lei

Preț: 172.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 258

Preț estimativ în valută:

32.96€ • 35.91$ • 27.77£

32.96€ • 35.91$ • 27.77£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Livrare express 19-25 martie pentru 33.51 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780226826554

ISBN-10: 0226826554

Pagini: 376

Ilustrații: 25 halftones

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Chicago Press

Colecția University of Chicago Press

Seria Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute

ISBN-10: 0226826554

Pagini: 376

Ilustrații: 25 halftones

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Chicago Press

Colecția University of Chicago Press

Seria Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute

Notă biografică

Victor Seow is assistant professor of the history of science at Harvard University. A historian of technology, science, and industry, he specializes in China and Japan and in histories of energy and work.

Extras

I came in search of the origins of China’s modern industrialization. I found, instead, the beginnings of its end. Before arriving in the coal-mining city of Fushun in the summer of 2011, I had seen old photographs and read historical accounts of its colossal open pit, first excavated by Japanese technocrats almost a century earlier. Pictures of the site showed an expansive industrial landscape molded by the machine: large excavators, electric- and steam- powered shovels, and dump cars hewing rock and moving earth to bring the cavity into being. The Japanese poet Yosano Akiko 與謝野晶子(1878–1942), who visited Fushun in 1928, described the mine as “a ghastly and grotesque form of a monster from the earth, opening its large maw toward the sky.” At first glance, the real thing did not disappoint.

It would have been easy to mistake the gigantic depression in the ground for a natural formation such as a valley were the sides not cut into steps of recognizable regularity: like terrace farming, but for harvesting shale and coal. I had been brought to the pit by a colliery representative eager to show off the sight. As our car trundled down a rocky road into its depths, I could not help but notice that the mine was far less busy than I had anticipated. Along our descent, we passed by a single dump truck loaded with debris. Imposing though it was— its wheels twice the height of our sedan— it appeared to be the only sign of work on site. Overhead, the sky was almost too blue for an industrial city, certainly so for one that for decades boasted East Asia’s largest coal-mining operations and that was once known as “Coal Capital” (in Chinese, 煤都; in Japanese, 炭都).

Fushun is located in Liaoning, the southernmost of the three provinces that make up China’s Northeast—a region formerly referred to as “Manchuria.” Sandwiched between layers of green mudstone, oil shale, tuff, and basalt, massive stores of coal lie beneath the city. For the past hundred or so years, this coal has been mined in spades. The South Manchuria Railway Company (南滿洲鐵道株式會社; “Mantetsu” [滿鐵], for short), the Japanese colonial corporation that ran Fushun’s coal mines for much of the first half of the twentieth century, developed them into an extractive enterprise of staggering proportions. In 1933, Fushun accounted for almost four-fifths of Manchuria’s coal output and more than a sixth of the coal produced in the Japanese metropole and its colonies. It was the pitch-black heart of Japan’s empire of energy.

The Chinese Communists continued to exploit Fushun’s carbon resources after taking control of the area in 1948. In 1952, this colliery, then till China’s largest, produced over 8 percent of the country’s coal. Decades later, the speed and scale of its extraction have proven unsustainable. Fushun’s current annual output is less than three million tons, roughly a third of its 1936 prewar peak and a sixth of its 1960 postwar height. Wasteful mining practices in the past have compromised present and future production. While about a third of the estimated 1.5 billion tons of total coal deposits remain in the ground, mining these reserves risks triggering landslides and subsidence that have caused infrastructure to crack and buildings to sink. According to a 2012 government report, as much as two-thirds of Fushun’s urban area rests on unstable ground. As one recent commentator puts it, “today the mineral that helped turn the city into a booming metropolis of 2.2 million threatens to bury it.”

This book explores how Chinese and Japanese states, in attempting to master the fossil fuels that powered their industrial aspirations, undertook large-scale technological projects of energy extraction that ultimately exacted considerable human and environmental costs. Nowhere is this more evident than in Fushun. Although the former Coal Capital’s fortunes may now be flagging, the pattern of fossil-fueled development that enabled its rise persists into the present. As we confront a planetary crisis precipitated by copious carbon consumption, the history of the Fushun colliery offers us a genealogy of our current predicament.

Opened by Chinese merchants at the start of the last century, Fushun’s coal mines were occupied by Japan during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and placed under Mantetsu’s management soon after. Following the fall of Japan’s empire in 1945, the Fushun colliery was seized first by the Soviets, then the Chinese Nationalists, and finally the Chinese Communists, under whose control it has since remained as a state-owned enter-prise. Throughout, operators maximized their hauls by deploying various technologies of extraction. They turned not only to methods like open-pit mining and hydraulic stowage to more completely extract carbon energy from the earth but also to mechanisms like fingerprinting and calorie counting to do the same with human labor. Fushun was the model of modern coal mining in China and Japan, and images of its immense open pit fed fantasies of energy-intensive industrial modernity in Tokyo, Nanjing, Beijing, and beyond.

The coal mined at Fushun and at other sites of energy extraction around the globe catalyzed a distinctive sociotechnical apparatus that presented itself as the epitome of modernity— universal, scientific, inevitable. For all their differences as political regimes, the imperial Japanese, Chinese Nationalist, and Chinese Communist states that controlled Fushun at varying times shared a decidedly technocratic vision in relation to carbon resources. This vision involved marshalling science and technology toward the exploitation of fossil fuels for statist ends. It was further characterized by an embrace of coal- fired development, a focus on heavy industrial expansion, a fixation on national autarky, an interest in labor-saving mechanization, a privileging of cheap energy, and a pegging of economic growth to increases in coal production and consumption. At the same time, that states saw in carbon energy a means to modernity engendered for them tensions between a fear of fuel scarcity and a faith in securing, largely through technoscientific means, a near limitless fuel supply. The emergence of this particularly modern regime of energy extraction that I call “carbon technocracy” is the subject of this book.

It would have been easy to mistake the gigantic depression in the ground for a natural formation such as a valley were the sides not cut into steps of recognizable regularity: like terrace farming, but for harvesting shale and coal. I had been brought to the pit by a colliery representative eager to show off the sight. As our car trundled down a rocky road into its depths, I could not help but notice that the mine was far less busy than I had anticipated. Along our descent, we passed by a single dump truck loaded with debris. Imposing though it was— its wheels twice the height of our sedan— it appeared to be the only sign of work on site. Overhead, the sky was almost too blue for an industrial city, certainly so for one that for decades boasted East Asia’s largest coal-mining operations and that was once known as “Coal Capital” (in Chinese, 煤都; in Japanese, 炭都).

Fushun is located in Liaoning, the southernmost of the three provinces that make up China’s Northeast—a region formerly referred to as “Manchuria.” Sandwiched between layers of green mudstone, oil shale, tuff, and basalt, massive stores of coal lie beneath the city. For the past hundred or so years, this coal has been mined in spades. The South Manchuria Railway Company (南滿洲鐵道株式會社; “Mantetsu” [滿鐵], for short), the Japanese colonial corporation that ran Fushun’s coal mines for much of the first half of the twentieth century, developed them into an extractive enterprise of staggering proportions. In 1933, Fushun accounted for almost four-fifths of Manchuria’s coal output and more than a sixth of the coal produced in the Japanese metropole and its colonies. It was the pitch-black heart of Japan’s empire of energy.

The Chinese Communists continued to exploit Fushun’s carbon resources after taking control of the area in 1948. In 1952, this colliery, then till China’s largest, produced over 8 percent of the country’s coal. Decades later, the speed and scale of its extraction have proven unsustainable. Fushun’s current annual output is less than three million tons, roughly a third of its 1936 prewar peak and a sixth of its 1960 postwar height. Wasteful mining practices in the past have compromised present and future production. While about a third of the estimated 1.5 billion tons of total coal deposits remain in the ground, mining these reserves risks triggering landslides and subsidence that have caused infrastructure to crack and buildings to sink. According to a 2012 government report, as much as two-thirds of Fushun’s urban area rests on unstable ground. As one recent commentator puts it, “today the mineral that helped turn the city into a booming metropolis of 2.2 million threatens to bury it.”

This book explores how Chinese and Japanese states, in attempting to master the fossil fuels that powered their industrial aspirations, undertook large-scale technological projects of energy extraction that ultimately exacted considerable human and environmental costs. Nowhere is this more evident than in Fushun. Although the former Coal Capital’s fortunes may now be flagging, the pattern of fossil-fueled development that enabled its rise persists into the present. As we confront a planetary crisis precipitated by copious carbon consumption, the history of the Fushun colliery offers us a genealogy of our current predicament.

Opened by Chinese merchants at the start of the last century, Fushun’s coal mines were occupied by Japan during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and placed under Mantetsu’s management soon after. Following the fall of Japan’s empire in 1945, the Fushun colliery was seized first by the Soviets, then the Chinese Nationalists, and finally the Chinese Communists, under whose control it has since remained as a state-owned enter-prise. Throughout, operators maximized their hauls by deploying various technologies of extraction. They turned not only to methods like open-pit mining and hydraulic stowage to more completely extract carbon energy from the earth but also to mechanisms like fingerprinting and calorie counting to do the same with human labor. Fushun was the model of modern coal mining in China and Japan, and images of its immense open pit fed fantasies of energy-intensive industrial modernity in Tokyo, Nanjing, Beijing, and beyond.

The coal mined at Fushun and at other sites of energy extraction around the globe catalyzed a distinctive sociotechnical apparatus that presented itself as the epitome of modernity— universal, scientific, inevitable. For all their differences as political regimes, the imperial Japanese, Chinese Nationalist, and Chinese Communist states that controlled Fushun at varying times shared a decidedly technocratic vision in relation to carbon resources. This vision involved marshalling science and technology toward the exploitation of fossil fuels for statist ends. It was further characterized by an embrace of coal- fired development, a focus on heavy industrial expansion, a fixation on national autarky, an interest in labor-saving mechanization, a privileging of cheap energy, and a pegging of economic growth to increases in coal production and consumption. At the same time, that states saw in carbon energy a means to modernity engendered for them tensions between a fear of fuel scarcity and a faith in securing, largely through technoscientific means, a near limitless fuel supply. The emergence of this particularly modern regime of energy extraction that I call “carbon technocracy” is the subject of this book.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Note on Conventions

Introduction / Carbon Technocracy /

One / Vertical Natures /

Two / Technological Enterprise /

Three / Fueling Anxieties /

Four / Imperial Extraction /

Five / Nationalist Reconstruction /

Six / Socialist Industrialization /

Epilogue / Exhausted Limits /

Acknowledgments /

Bibliography /

Index /

Note on Conventions

Introduction / Carbon Technocracy /

One / Vertical Natures /

Two / Technological Enterprise /

Three / Fueling Anxieties /

Four / Imperial Extraction /

Five / Nationalist Reconstruction /

Six / Socialist Industrialization /

Epilogue / Exhausted Limits /

Acknowledgments /

Bibliography /

Index /

Recenzii

"The book is not only an erudite history, but also—perhaps most critically—an urgent call for environmental intervention, as when Seow laments that 'unless radical transformations take place,' his offspring’s generation will inherit the 'world that carbon made, so deeply despoiled and unjust.' An ambitious, scholarly study of the societal complications of energy extraction."

"Years of research allow Seow to trace the multifarious consequences of seemingly mundane geology. To say he mastered the technical minutia is to risk considerable understatement. Seow delineates coal’s role in East Asia’s industrialization, tracing its mutual dependence with every sinew of the wider society."

“Carbon Technocracy, Seow’s impressive debut . . . centers on one city, Fushun. The first Ming-China outpost to fall to the Manchus in 1618, the former fortress and trade site was home to the largest coal-mining operation in East Asia for much of the last century. . . . A crucial contribution to the understandings of East Asia, of imperialism. . . . and of science and the modern state.”

“Carbon Technocracy balances macro-level questions about the mutual constitution of nation and global energy regimes with a sensitivity to individual laborers caught up in these machinations.”

“A particular strength of this book lies in Seow’s befitting elucidation of the science and technology of coal mining, which allows the materiality of Fushun’s coal deposits to shine through the convoluted social, political, and economic realities of energy regimes. . . . This is a book of the history of technology with substantive technology.”

“Seow’s book arrives as the climatic effects of fossil fuel consumption have become alarmingly apparent everywhere. Recent floods in Pakistan exacerbated by melting glaciers, drought and unrelenting heat in China, Europe, the U.S., and all around the globe bespeak the urgency of understanding the history that Seow traces. While Carbon Technocracy does not give much cause for optimism that a transition to renewable forms of energy in China will be any less technocratic than the exploitation of fossil fuels has been, it is an insightful and engaging book that should shape conversations about East Asia and energy for years to come.”

“The beauty in his crafting of the story, the weaving together of various conceptual threads, and the blending of different source material is in how Seow both recreates the physical and mental worlds of industrial northeast China and frames up a compelling argument that helps us better understand their fabric. The work that Seow has done to pull together research from government and company records, a variety of gray literature, travel diaries, oral histories, and private collections of mining engineers from China, Japan, Taiwan, and the United States is staggering.”

“Seow’s timely new book, Carbon Technocracy, offers a deeply researched account for how China came to construct its carbon economy. . . . Through Fushun, Seow succeeds in demonstrating how the broader global embrace of development based on fossil fuels was built on similar unstable grounds at enormous costs to human lives and the environment.”

“This volume is a very worthy addition to the historiographical field: first and foremost for its detailed case study of such a globally significant coal mine, but also for the interesting and insightful way in which it emphasizes the interconnectedness of calorific power and political power—not just within the specific context of East Asian state-building, but also more broadly. It should most certainly be required reading for students and scholars of East Asian mining history in particular, but also for anyone interested in twentieth-century mining and energy history in general.”

“A fascinating and important piece of scholarship that should interest scholars of industrial modernity, regardless of their disciplinary allegiances. . . . Seow takes a single mining site as his focus: Fushun, located in the northeastern region of China known then as Manchuria. This methodological choice enables a highly successful blend of macro- and micro-histories throughout the book.”

“China, the world’s largest consumer of fossil fuels today, has until recently been neglected by energy historians. Carbon Technocracy corrects this injustice with great erudition and depth. Seow, an assistant professor of the history of science at Harvard University, has spent more than a decade studying the Fushun colliery, known for most of the twentieth century as East Asia’s coal capital. The result is a fascinating case study on the history of a fossil fuel hub under different political regimes over more than a century.”

“Seow’s brilliant new book, Carbon Technocracy: Energy Regimes in Modern East Asia, is the latest addition to the scholarship on the history of energy in East Asia. . . . By tracing the rise of carbon technocracy, Seow provides historians of East Asia with a new way of understanding the region; his refreshing approach joins the field’s two predominant narratives, namely empire building and national struggle. More importantly, he is meticulous and thoughtful in evaluating the relationship between colonialism and the industrial modernity that was fostered under the dome of Japan’s empire. While acknowledging the fossil fuel–driven modernity facilitated by the Japanese in Manchuria, he underlines its exploitative and repressive nature. By paying attention to the human cost of coal extraction, done by coerced labor under total war or by organized labor competition in a socialist society, the author takes a humanist approach and compassionate attitude in unpacking the rise of carbon technocracy in East Asia.”

“Carbon Technocracy is a beautifully written historical work of both deep erudition and remarkable humanity. . . . Seow’s concept of carbon technocracy offers a promising framework for exploring several critical conceptual and ethical issues in the history of scientifically driven state formation and resource management.”

“Carbon Technocracy redefines the contours of the field of energy history in East Asia.”

"A brilliant account of energy and empire, industrial hubris, and ecological destruction told through the story of the coal capital of China. Providing an alternative global history of technology, the book argues for a distinctive understanding of the role of fossil fuel energy in shaping the political order of East Asia in the age of carbon."

"Impressive in scope and significance, Carbon Technocracy offers compelling evidence of the historical relationship between the fossil fuel economy and the rise of the modern nation-state in China and beyond. Readers will gain a fresh understanding of the roots of fossil fuel addiction and its consequences, which encompass not only ecological destruction but also violent exploitation of laborers and increased state capacity for social control. Through a rich historical excavation centered in one Manchurian coal mine, Seow demonstrates in no uncertain terms why we must look beyond technocratic solutions as we struggle to survive the climate crisis."

"Seow shows that civilizations built on coal undermine their own foundations with each strike of the shovel. His exploration of carbon technocracy highlights how the desire for technological progress and development runs along a deep seam of violence. Profoundly humane and thoughtful."

"Focusing on the history of the Fushun coal mine in Northeast China, this engaging book traces the worlds that coal made across twentieth-century East Asia. Shifting seamlessly from the abstract structures of states and economies to the everyday lives of engineers and workers, Seow tells the story of the big science, big engineering, and big technology that made up the carbon foundation of both Imperial Japan and Communist China. A probing account of the origins and challenges of the climate crisis."

"Drawing on an impressive range of sources, Seow reveals the intertwined stories of the Fushun colliery and the succession of state regimes that have drawn on Fushun’s material (and even rhetorical) power, from the contestation among Chinese, Russian, and Japanese interests at the turn of the last century through the consolidation of the People’s Republic of China. The clarity of Seow’s thinking, the felicity of his prose, and the significance of his topic will ensure a large audience among modern East Asian historians, energy historians, and the many scholars in environmental studies and environmental humanities who focus on carbon-driven climate change. Clearly written and very thoughtfully conceived."