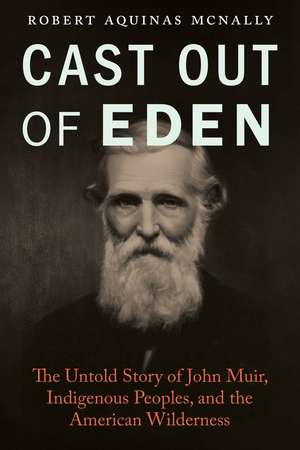

Cast Out of Eden: The Untold Story of John Muir, Indigenous Peoples, and the American Wilderness

Autor Robert Aquinas McNallyen Limba Engleză Hardback – mai 2024

Cast Out of Eden tells this neglected part of Muir’s story—from Lowland Scotland and the Wisconsin frontier to the Sierra Nevada’s granite heights and Alaska’s glacial fjords—and his take on the tribal nations he encountered and embrace of an ethos that forced those tribes from their homelands. Although Muir questioned and worked against Euro-Americans’ distrust of wild spaces and deep-seated desire to tame and exploit them, his view excluded Native Americans as fallen peoples who stained the wilderness’s pristine sanctity. Fortunately, in a transformation that a resurrected and updated Muir might approve, this long-standing injustice is beginning to be undone, as Indigenous nations and the federal government work together to ensure that quintessentially American lands from Bears Ears to Yosemite serve all Americans equally.

Preț: 208.75 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 313

Preț estimativ în valută:

39.94€ • 41.79$ • 33.18£

39.94€ • 41.79$ • 33.18£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496227263

ISBN-10: 1496227263

Pagini: 328

Ilustrații: 13 photographs, index

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.66 kg

Editura: BISON BOOKS

Colecția Bison Books

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496227263

Pagini: 328

Ilustrații: 13 photographs, index

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.66 kg

Editura: BISON BOOKS

Colecția Bison Books

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Robert Aquinas McNally is a freelance writer and editor based in Concord, California. He is the author of nine books, including The Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age (Nebraska, 2021).

Extras

1

From Old World to New

It was an evening seemingly like any other in the deep Scottish winter of

1849. Eleven-year-old John Muir and younger brother David were nestled

with their maternal grandfather beside the fire, catching a few warm minutes

before heading off to study for school the next morning. Daniel Muir, the

boys’ father, entered the room where the fire’s glow lit the far wall. “Bairns,

you needna learn your lessons the nicht,” he announced in a Scots dialect

gone unusually ebullient, “for we’re gan to America the morn!”

When Muir told this story more than sixty years later, he remembered

imagining a door opening to untold wonders. This eleven-year-old was trading

flat grain fields along the windblown North Sea for a country green with

promise. He envisioned a big-leafed canopy of sugar maples and imagined

the sky above it filled with hawks, eagles, and passenger pigeons in sun-darkening

numbers. Propelled westward by hope and social forces he little

understood, the young John Muir was about to become an immigrant bent

on becoming a settler.

His father, Daniel, was a man on a cosmic mission whose energy, if not its

dogma, he would pass on to his eldest son. Years of seeking religious truth

had convinced Daniel that his personal path toward holiness led to North

America. It was time to make the move God willed.

Born in 1804 in Manchester, England, where his soldier father was stationed,

Daniel was orphaned as an infant. His sister, Mary, eleven years his

elder, took him in after she married. Once he grew big enough, Daniel

took on the endless toil of a farm laborer, a harsh existence that likely

played into his soul-deep joylessness. It contributed, too, to his conversion

as a teenager to evangelical religion, the emotional Calvinism that drew in

Scotland’s poor, landless, working-class masses. The newly hooked Daniel

became God-guided. He set out to find the truest of the true while, like his

father, he enlisted in the British Army and rose in the ranks. Stationed as a

recruiter in the port town of Dunbar, east of Edinburgh, Sergeant Muir met

and married Helen Kennedy, who had inherited a grain-and-feed store from

her father. Daniel convinced Helen to buy out his enlistment contract, and

he took on managing the store. Always a hard worker, he turned it into a

small success, and the business became his alone when his wife died suddenly.

Daniel soon married another local young woman, Ann Gilrye, whose

father was a prosperous meat merchant on Dunbar’s High Street. Children

followed quickly. First came Margaret and Sarah, then John, followed by

David, Daniel Jr., and twins Mary and Annie, all born in Scotland. The last

Muir child, Joanna, would arrive in the United States. Expanding the grain-and-

feed business into the first floor of a larger building down the street,

the energetic Daniel turned the floors above into domestic quarters. In his

spare time he grew a garden and was “always trying to make it as much like

Eden as possible,” John recalled. Meanwhile, his family grew, his status rose,

and he won election to the city council.

Daniel’s decision to leave success behind turned on religion. He had for

some time been a member of the Dunbar congregation of the Secessionist

Church, which split from the Church of Scotland over the issue of ministry.

The Church of Scotland held that only landowners could participate in

selecting ministers; the Secessionists argued that the landless, too, should

have a say. Yet, as the years passed, Daniel came to believe that even this

arrangement placed too much human mediation between the individual

believer and God. The faithful should minister to themselves.

In this rebellious frame of mind, Daniel learned of Alexander Campbell,

a Secessionist minister’s son who was embracing radical religious democracy.

A Scot born in Ireland’s Presbyterian north, Campbell studied divinity at the

University of Glasgow and then left to join his father, who had emigrated to

Pennsylvania. The father-son preaching duo created a stir along the settlement

frontier, offering their version of the American religious revival that led

also to the Shakers, the Rappites, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Spiritualists,

and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Calling themselves

the Disciples of Christ, the Campbells and their followers flourished, soon

becoming the fastest-growing denomination in the young republic.

In 1847 Alexander Campbell returned to Scotland on a preaching tour and

held forth in Edinburgh one hot August day. There, it is likely, Daniel Muir

joined the sweaty, adoring audience. Finding in Campbell the charismatic

leader he was seeking, Daniel soon converted to the radically egalitarian,

evangelical Protestantism practiced by the Disciples of Christ. The Disciples

looked beyond Europe and its entrenched hierarchies to democratic North

America as the land promised to the young denomination’s true believers.

Within five months, Daniel resolved to forsake the familiar and embrace

this new world. On the morning of February 19, 1849, Muir headed off with

three of his children, John among them, to make their way to America and

prepare a home to receive the rest of the family. The first leg was a train

trip to Glasgow, where Muir booked passage on the Warren, a three-masted,

modest-sized packet ship built only two years earlier in Maine and registered

in New York. The Warren sailed on a regular schedule between Glasgow and

New York carrying both passengers and cargo. On February 24, five days

after the Muirs left Dunbar, the ship sailed out of Edinburgh’s Broomielaw

Harbor toward the open Atlantic.

From Old World to New

It was an evening seemingly like any other in the deep Scottish winter of

1849. Eleven-year-old John Muir and younger brother David were nestled

with their maternal grandfather beside the fire, catching a few warm minutes

before heading off to study for school the next morning. Daniel Muir, the

boys’ father, entered the room where the fire’s glow lit the far wall. “Bairns,

you needna learn your lessons the nicht,” he announced in a Scots dialect

gone unusually ebullient, “for we’re gan to America the morn!”

When Muir told this story more than sixty years later, he remembered

imagining a door opening to untold wonders. This eleven-year-old was trading

flat grain fields along the windblown North Sea for a country green with

promise. He envisioned a big-leafed canopy of sugar maples and imagined

the sky above it filled with hawks, eagles, and passenger pigeons in sun-darkening

numbers. Propelled westward by hope and social forces he little

understood, the young John Muir was about to become an immigrant bent

on becoming a settler.

His father, Daniel, was a man on a cosmic mission whose energy, if not its

dogma, he would pass on to his eldest son. Years of seeking religious truth

had convinced Daniel that his personal path toward holiness led to North

America. It was time to make the move God willed.

Born in 1804 in Manchester, England, where his soldier father was stationed,

Daniel was orphaned as an infant. His sister, Mary, eleven years his

elder, took him in after she married. Once he grew big enough, Daniel

took on the endless toil of a farm laborer, a harsh existence that likely

played into his soul-deep joylessness. It contributed, too, to his conversion

as a teenager to evangelical religion, the emotional Calvinism that drew in

Scotland’s poor, landless, working-class masses. The newly hooked Daniel

became God-guided. He set out to find the truest of the true while, like his

father, he enlisted in the British Army and rose in the ranks. Stationed as a

recruiter in the port town of Dunbar, east of Edinburgh, Sergeant Muir met

and married Helen Kennedy, who had inherited a grain-and-feed store from

her father. Daniel convinced Helen to buy out his enlistment contract, and

he took on managing the store. Always a hard worker, he turned it into a

small success, and the business became his alone when his wife died suddenly.

Daniel soon married another local young woman, Ann Gilrye, whose

father was a prosperous meat merchant on Dunbar’s High Street. Children

followed quickly. First came Margaret and Sarah, then John, followed by

David, Daniel Jr., and twins Mary and Annie, all born in Scotland. The last

Muir child, Joanna, would arrive in the United States. Expanding the grain-and-

feed business into the first floor of a larger building down the street,

the energetic Daniel turned the floors above into domestic quarters. In his

spare time he grew a garden and was “always trying to make it as much like

Eden as possible,” John recalled. Meanwhile, his family grew, his status rose,

and he won election to the city council.

Daniel’s decision to leave success behind turned on religion. He had for

some time been a member of the Dunbar congregation of the Secessionist

Church, which split from the Church of Scotland over the issue of ministry.

The Church of Scotland held that only landowners could participate in

selecting ministers; the Secessionists argued that the landless, too, should

have a say. Yet, as the years passed, Daniel came to believe that even this

arrangement placed too much human mediation between the individual

believer and God. The faithful should minister to themselves.

In this rebellious frame of mind, Daniel learned of Alexander Campbell,

a Secessionist minister’s son who was embracing radical religious democracy.

A Scot born in Ireland’s Presbyterian north, Campbell studied divinity at the

University of Glasgow and then left to join his father, who had emigrated to

Pennsylvania. The father-son preaching duo created a stir along the settlement

frontier, offering their version of the American religious revival that led

also to the Shakers, the Rappites, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Spiritualists,

and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Calling themselves

the Disciples of Christ, the Campbells and their followers flourished, soon

becoming the fastest-growing denomination in the young republic.

In 1847 Alexander Campbell returned to Scotland on a preaching tour and

held forth in Edinburgh one hot August day. There, it is likely, Daniel Muir

joined the sweaty, adoring audience. Finding in Campbell the charismatic

leader he was seeking, Daniel soon converted to the radically egalitarian,

evangelical Protestantism practiced by the Disciples of Christ. The Disciples

looked beyond Europe and its entrenched hierarchies to democratic North

America as the land promised to the young denomination’s true believers.

Within five months, Daniel resolved to forsake the familiar and embrace

this new world. On the morning of February 19, 1849, Muir headed off with

three of his children, John among them, to make their way to America and

prepare a home to receive the rest of the family. The first leg was a train

trip to Glasgow, where Muir booked passage on the Warren, a three-masted,

modest-sized packet ship built only two years earlier in Maine and registered

in New York. The Warren sailed on a regular schedule between Glasgow and

New York carrying both passengers and cargo. On February 24, five days

after the Muirs left Dunbar, the ship sailed out of Edinburgh’s Broomielaw

Harbor toward the open Atlantic.

Cuprins

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Prologue: The View from Sheepy Ridge, One

Part 1. A Voice Crying for Wilderness

1. From Old World to New

2. A Widening World Darkens

3. The Ungodliness of Dirt

Part 2. East of Eden

4. Yosemite’s Genocidal Backstory

5. Return to the Garden

6. Well Done for Wildness!

7. Missionary to the Tlingits

8. One Savage Living on Another

9. The Grapes of Wealth

Part 3. One Last Time

10. Wilderness Influencer

11. On Top of the World

12. River Out of Eden

13. Leave Only Footprints, Take Only Pictures

14. Bettering America’s Best Idea

Epilogue: The View from Sheepy Ridge, Two

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Prologue: The View from Sheepy Ridge, One

Part 1. A Voice Crying for Wilderness

1. From Old World to New

2. A Widening World Darkens

3. The Ungodliness of Dirt

Part 2. East of Eden

4. Yosemite’s Genocidal Backstory

5. Return to the Garden

6. Well Done for Wildness!

7. Missionary to the Tlingits

8. One Savage Living on Another

9. The Grapes of Wealth

Part 3. One Last Time

10. Wilderness Influencer

11. On Top of the World

12. River Out of Eden

13. Leave Only Footprints, Take Only Pictures

14. Bettering America’s Best Idea

Epilogue: The View from Sheepy Ridge, Two

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Recenzii

“A convincing, corrective portrait of a revered but flawed man, and of a movement’s original sins. It ends on a note of modest hope, as McNally jumps to the present to detail how Native Americans are claiming their rightful places in the nation’s national parks.”—Peter Fish, San Francisco Chronicle Datebook

"A revealing biography, Cast Out of Eden details the hypocrisy, cruelty, and astonishing achievements of John Muir."—Foreword Reviews

"This is a well-written exploration of John Muir's life and legacy."—James H. McDonald, New York Journal of Books

“To most Americans, John Muir is a folk hero, a writer and thinker who inspired the nation’s wilderness preservation movement. Robert McNally’s powerful new biography offers a darker vision, situating Muir’s life and work within America’s violent campaigns of Indigenous land dispossession and genocide. Cast Out of Eden is a vivid and absorbing read, one that will challenge everything you think you know about one of America’s most famous environmentalists.”—Megan Kate Nelson, author of The Three-Cornered War, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History

“Robert Aquinas McNally takes John Muir off his pedestal and paints him as a man of his times, blinded by his belief in white supremacy and his faith in manifest destiny. In doing so, McNally provides a helpful, needed context for our own era and its conflicts.”—Margaret Verble (Cherokee Nation), author of Maud’s Line, finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction

“Robert Aquinas McNally lays out not only John Muir’s public love affair with the wild spaces that became national parks but also his deep-seated disdain for the American Indians whose homelands those parks expropriated. A page-turning, eye-opening read that delves unflinchingly into the dark side of preservation politics, then turns toward a future where wild spaces work their natural magic for all—not just some—Americans, including the tribes.”—Susan Devan Harness (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes), author of the award-winning Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption

“Robert Aquinas McNally brings John Muir and his world to life, warts and all, with an eye for gripping historical details. An urgent story for our troubled times, this is narrative nonfiction at its best!”—Boyd Cothran, author of The Edwin Fox: How an Ordinary Sailing Ship Connected the World in the Age of Globalization, 1850–1914

“A thought-provoking masterpiece. Following the life and achievements of John Muir, ‘Father of the National Parks,’ McNally masterfully shows how one of America’s greatest achievements—the preservation of our wildest places—is indelibly tied to one of our most abject failures—the treatment of the Native Americans who lived there.”—Matthew Kerns, Spur and Western Heritage Award–winning author of Texas Jack: America’s First Cowboy Star

“Robert McNally has added to John Muir’s legacy in a way that will hook both conservationists and those with little interest in wilderness. At a time when the natural world has once again become the protagonist of our story, McNally breaks down the complicated and conflicted relationship with nature to show how our long-standing attitudes toward wild spaces grew from the limited perspective of an elite few. This is the story not of a single man but of a time, place, and culture that created a public figure who has hugely influenced how we interact today with the natural world—for good and ill.”—Katya Cengel, author of From Chernobyl with Love

“Robert Aquinas McNally throws back the curtain on John Muir and our deeply held beliefs about how the American wilderness came to be. A dogged researcher, McNally offers sometimes unsettling facts but steeps such accounts in a deep reverence for storytelling. As hard-hitting as it is lyrical, the profound truth at the heart of this book invites all of us to rethink what we’ve been told about Indigenous peoples.”—Melissa Fraterrigo, author of Glory Days

Descriere

Cast Out of Eden explores John Muir’s role in the dispossession of Native Americans from U.S. wild lands and points a way toward reconciliation.