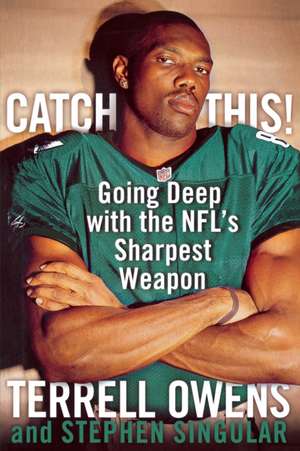

Catch This!: Going Deep with the NFL's Sharpest Weapon

Autor Terrell Owens, Stephen Singularen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 mai 2011

It isn't just that he holds the NFL record for catches in a single game (twenty) or that he's the most feared wide receiver in the game. It's also his penchant for unique self-expression -- spiking the ball on the midfield Texas lone star in front of a hostile Dallas Cowboy crowd, pulling a Sharpie from his sock to sign a game ball after a touchdown, and dancing with a cheerleader's pom-poms after another TD. Never politically correct and always controversial and colorful on and off the field, Terrell Owens has transformed himself into "TO," the outrageous gridiron personality who has rocked the entire NFL and the sports landscape. But Owens is more than touchdowns, dancing, and celebrations. In this wickedly insightful book, he's full of sharp-eyed observations on the contentious, demanding, insane phenomenon that is pro football.

In Catch This! Owens takes readers back to his hardscrabble childhood in rural Alabama, where he was raised by a stern grandmother and loving mother. By the time he won an athletic scholarship for football at the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga, the once small, bullied boy had transformed himself into a very large man with a super body and an iron will to succeed. He takes us behind his apprenticeship to -- and eventual eclipsing of -- the legendary 49ers wide receiver Jerry Rice. He pulls no punches when it comes to his extremely public fight with San Francisco coach Steve Mariucci -- a relationship so sour that they didn't speak at all during the crucial final weeks of the 2001 season. And, finally, he lets loose on the free agent scandal that shook the NFL in 2004 -- and reveals the truth behind the NFL's attempt to deny him free agency, his fraudulent trade to the Baltimore Ravens, and his ultimate happy landing with the Philadelphia Eagles.

For those who think they know both Terrell Owens and TO, catch this story.

Preț: 112.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.50€ • 23.37$ • 18.08£

21.50€ • 23.37$ • 18.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781451631685

ISBN-10: 1451631685

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:11000

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1451631685

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:11000

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Extras

Chapter 1

A couple of years ago, I went back home to Alexander City, Alabama, about an hour's drive south and east of Birmingham. I don't go home much anymore, but my mom still lives there, along with a few old friends. I was eating at a local restaurant when a white family came in and sat down a few tables away. Their son was about three years old and had a high, loud voice, the kind that grabs your attention. He kept pointing at me.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy?" he said. "Who's that nigger over there?"

I tried to ignore him, but that was impossible.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy?"

I've been trying to ignore insults like that ever since I was very small. I'm dark, and I grew up hearing racial slurs from everyone -- both black and white. Other black kids called me "Shine" and "Purple Pal." You can guess what the white kids called me. From the time I was a child, I had to learn not to react to people's stupidity and cruelty, even when that's all I wanted to do. I had to learn to let things go and to control myself, and I was trying to let this go in the restaurant. I just wanted to finish my meal, leave these people and this town behind, and not come back home again anytime soon. But the kid wouldn't be quiet.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy? Who's that nigger right there?"

Someone else in the café decided to stand up and walk over to the family's table and tell them that I was Terrell Owens, Pro Bowl wide receiver for the San Francisco 49ers, who'd grown up in Alexander City and played ball at the local high school.

The family looked stunned to hear this, and it shut the boy up, at least for a short while. His parents were so embarrassed that they turned away from me and talked between themselves. But then I heard a sound and saw the kid approaching me.

His parents had sent him to my table for my autograph. I was, I guess, the most famous person Alex City had ever produced. When the child got to my table, I looked right at him and didn't say anything, but very slowly and neatly wrote out my signature, using my best handwriting and putting the number 81 on the piece of paper. I always do this when I give out an autograph. I was raised to be polite, to forgive and to accept and to go on. I've tried to do that my whole life -- with myself and my family and others. That's why I gave the boy my autograph. I wanted his parents to know that it wasn't the kid's fault that he was acting this way -- no three-year-old knows this stuff unless someone has taught it to him, so he didn't deserve to be punished. Racists aren't born but made, one child at a time, one word at a time, and until adults break this chain of ignorance and hatred, it will never stop.

I also wanted his parents to know, just as I want the National Football League to know, that they don't get to define me or to control me or my feelings. That's my job, on the football field and in life. They don't get to tell me when to give an autograph or when to celebrate or when to cry. I'm the only one who can decide what's right for me -- and I'm willing to pay the price for being who I am. My grandmother and my mom taught me that I need to walk through this world with a strong mind and a big heart, so that's my goal. I don't always reach it. Sometimes I stumble, and sometimes I come close to falling, but then I refocus and try to learn and get better.

I've been doing this for as long as I can remember.

* * *

f0

Football is not the most important thing in my life. It's not even the second most important thing. It's faith, family, and football, in that order. I don't think of myself as a professional football player but as an athlete who ended up in the NFL. I wish it were different. If things had gone the way I wanted them to, I'd be playing pro basketball now instead of football, and then my mom could see my face whenever I made a basket or grabbed a rebound or blocked a shot. She's the reason I started celebrating in the end zone in the first place: I wanted her to see me on television. She watched the 49ers games down in Alabama, and the only way I could make sure that the camera stayed on me was to score a touchdown and then do something nobody had ever done before. This led to dancing on the star in the middle of the field in Dallas, and that led to Sharpie and to shaking the cheerleaders' pom-poms. Who knows what will happen next? Before each game, I tell my mom to stay tuned for something new.

In the NBA, I could express myself naturally on the court without causing a national crisis, but the NFL -- the No Fun League -- isn't like that. It's a lot like the military, where everyone is supposed to fall in line and be like everyone else. I'm not like anyone else. My family wasn't like anyone else's, so I wasn't raised like other people. I was raised to be myself and to tell the truth and to take the consequences for doing that. I'm not going to keep quiet or stay inside a box, the way many pro athletes do, even some very famous ones who've told me that the best road was to be politically correct at all times. That was best for them, not me. The NFL can't deal with me -- because they never know what I'm going to do next.

After I scored the winning touchdown against Seattle on Monday Night Football and then signed the ball with a Sharpie, some people in the NFL and the press called me an embarrassment to the sport, shameless, selfish, egotistical, and worse. Seattle coach Mike Holmgren took a major shot at me, and so did football commentators from coast to coast. You'd have thought I committed a crime, like some other players we could talk about in pro sports today. We've got guys charged with rape, with drug abuse, with beating their wives and girlfriends, and with murder. We've got rap sheets all over the league, and I brought disgrace to the league by carrying a pen in my sock and autographing a football? A lot of people in America have lost perspective about sports, and about life. Some of them are filled with judgment and even hate. Many have forgotten what love and acceptance are all about -- not to mention having fun. They forget that football is entertainment, and they have no idea what an athlete goes through to get into the NFL, let alone get into the end zone on Monday Night Football. If they did, they might feel like celebrating, too, when something goes right.

After Sharpie, the media began writing and talking about me as if they know who I am and what I stand for. They don't. Like many NFL owners and league executives, they don't know where I came from or what I believe in. They don't want to know too much about the hired hands who make their football machines go. They want us to do our jobs and stay in our places and shut up. They don't want to see or hear anything that will make them think very much about the people who work for them. The press can't understand that when I went to the star in Dallas, I wasn't trying to taunt anyone but was thanking and honoring God for all the blessings I've received and for all the things I've been able to do for my family. They want athletes to be role models for young people, but when I try to tell them about my spiritual foundation, they don't want to know about it. Real faith makes them nervous. Real life is too big or too scary compared with a football game. Athletes aren't supposed to be real people, only trained entertainers, but reality can get in the way of a good story or a cheap opinion.

I always tell people that if they really want to know who I am, they should look deeply into my eyes, because the reality and the truth are there. I'm a person just like yourself, with a heart and a history and a lot of feelings about my past. Look into my eyes, and maybe you'll understand why faith and family are so important to me and why football is just a way of serving them. Look into my eyes, and maybe you can learn where I'm from and why I want to celebrate after scoring a touchdown.

Look and listen.

Copyright © 2004 by Terrell Owens and Stephen Singular

A couple of years ago, I went back home to Alexander City, Alabama, about an hour's drive south and east of Birmingham. I don't go home much anymore, but my mom still lives there, along with a few old friends. I was eating at a local restaurant when a white family came in and sat down a few tables away. Their son was about three years old and had a high, loud voice, the kind that grabs your attention. He kept pointing at me.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy?" he said. "Who's that nigger over there?"

I tried to ignore him, but that was impossible.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy?"

I've been trying to ignore insults like that ever since I was very small. I'm dark, and I grew up hearing racial slurs from everyone -- both black and white. Other black kids called me "Shine" and "Purple Pal." You can guess what the white kids called me. From the time I was a child, I had to learn not to react to people's stupidity and cruelty, even when that's all I wanted to do. I had to learn to let things go and to control myself, and I was trying to let this go in the restaurant. I just wanted to finish my meal, leave these people and this town behind, and not come back home again anytime soon. But the kid wouldn't be quiet.

"Who's that nigger, Daddy? Who's that nigger right there?"

Someone else in the café decided to stand up and walk over to the family's table and tell them that I was Terrell Owens, Pro Bowl wide receiver for the San Francisco 49ers, who'd grown up in Alexander City and played ball at the local high school.

The family looked stunned to hear this, and it shut the boy up, at least for a short while. His parents were so embarrassed that they turned away from me and talked between themselves. But then I heard a sound and saw the kid approaching me.

His parents had sent him to my table for my autograph. I was, I guess, the most famous person Alex City had ever produced. When the child got to my table, I looked right at him and didn't say anything, but very slowly and neatly wrote out my signature, using my best handwriting and putting the number 81 on the piece of paper. I always do this when I give out an autograph. I was raised to be polite, to forgive and to accept and to go on. I've tried to do that my whole life -- with myself and my family and others. That's why I gave the boy my autograph. I wanted his parents to know that it wasn't the kid's fault that he was acting this way -- no three-year-old knows this stuff unless someone has taught it to him, so he didn't deserve to be punished. Racists aren't born but made, one child at a time, one word at a time, and until adults break this chain of ignorance and hatred, it will never stop.

I also wanted his parents to know, just as I want the National Football League to know, that they don't get to define me or to control me or my feelings. That's my job, on the football field and in life. They don't get to tell me when to give an autograph or when to celebrate or when to cry. I'm the only one who can decide what's right for me -- and I'm willing to pay the price for being who I am. My grandmother and my mom taught me that I need to walk through this world with a strong mind and a big heart, so that's my goal. I don't always reach it. Sometimes I stumble, and sometimes I come close to falling, but then I refocus and try to learn and get better.

I've been doing this for as long as I can remember.

* * *

f0

Football is not the most important thing in my life. It's not even the second most important thing. It's faith, family, and football, in that order. I don't think of myself as a professional football player but as an athlete who ended up in the NFL. I wish it were different. If things had gone the way I wanted them to, I'd be playing pro basketball now instead of football, and then my mom could see my face whenever I made a basket or grabbed a rebound or blocked a shot. She's the reason I started celebrating in the end zone in the first place: I wanted her to see me on television. She watched the 49ers games down in Alabama, and the only way I could make sure that the camera stayed on me was to score a touchdown and then do something nobody had ever done before. This led to dancing on the star in the middle of the field in Dallas, and that led to Sharpie and to shaking the cheerleaders' pom-poms. Who knows what will happen next? Before each game, I tell my mom to stay tuned for something new.

In the NBA, I could express myself naturally on the court without causing a national crisis, but the NFL -- the No Fun League -- isn't like that. It's a lot like the military, where everyone is supposed to fall in line and be like everyone else. I'm not like anyone else. My family wasn't like anyone else's, so I wasn't raised like other people. I was raised to be myself and to tell the truth and to take the consequences for doing that. I'm not going to keep quiet or stay inside a box, the way many pro athletes do, even some very famous ones who've told me that the best road was to be politically correct at all times. That was best for them, not me. The NFL can't deal with me -- because they never know what I'm going to do next.

After I scored the winning touchdown against Seattle on Monday Night Football and then signed the ball with a Sharpie, some people in the NFL and the press called me an embarrassment to the sport, shameless, selfish, egotistical, and worse. Seattle coach Mike Holmgren took a major shot at me, and so did football commentators from coast to coast. You'd have thought I committed a crime, like some other players we could talk about in pro sports today. We've got guys charged with rape, with drug abuse, with beating their wives and girlfriends, and with murder. We've got rap sheets all over the league, and I brought disgrace to the league by carrying a pen in my sock and autographing a football? A lot of people in America have lost perspective about sports, and about life. Some of them are filled with judgment and even hate. Many have forgotten what love and acceptance are all about -- not to mention having fun. They forget that football is entertainment, and they have no idea what an athlete goes through to get into the NFL, let alone get into the end zone on Monday Night Football. If they did, they might feel like celebrating, too, when something goes right.

After Sharpie, the media began writing and talking about me as if they know who I am and what I stand for. They don't. Like many NFL owners and league executives, they don't know where I came from or what I believe in. They don't want to know too much about the hired hands who make their football machines go. They want us to do our jobs and stay in our places and shut up. They don't want to see or hear anything that will make them think very much about the people who work for them. The press can't understand that when I went to the star in Dallas, I wasn't trying to taunt anyone but was thanking and honoring God for all the blessings I've received and for all the things I've been able to do for my family. They want athletes to be role models for young people, but when I try to tell them about my spiritual foundation, they don't want to know about it. Real faith makes them nervous. Real life is too big or too scary compared with a football game. Athletes aren't supposed to be real people, only trained entertainers, but reality can get in the way of a good story or a cheap opinion.

I always tell people that if they really want to know who I am, they should look deeply into my eyes, because the reality and the truth are there. I'm a person just like yourself, with a heart and a history and a lot of feelings about my past. Look into my eyes, and maybe you'll understand why faith and family are so important to me and why football is just a way of serving them. Look into my eyes, and maybe you can learn where I'm from and why I want to celebrate after scoring a touchdown.

Look and listen.

Copyright © 2004 by Terrell Owens and Stephen Singular

Notă biografică

Terrell Owens is a perennial all-pro wide receiver. In 2005 he became only the sixth receiver in NFL history with 100 touchdown receptions. His reality series, The T.O. Show airs on VH1. Terrell currently plays for Buffalo Bills.

Visit the author at www.terrellowens.com

Stephen Singular has authored or coauthored seventeen previous books, including numerous New York Times and Los Angeles Times bestsellers. His titles include Presumed Guilty: An Investigation into the JonBenet Ramsey Case, the Media, and the Culture of Pornography; and Anyone You Want Me to Be: A True Story of Sex and Death on the Internet, coauthored with legendary FBI profiler John Douglas. Formerly a staff writer for the Denver Post, he lives in Denver. Visit his website at www.stephensingular.com.

Visit the author at www.terrellowens.com

Stephen Singular has authored or coauthored seventeen previous books, including numerous New York Times and Los Angeles Times bestsellers. His titles include Presumed Guilty: An Investigation into the JonBenet Ramsey Case, the Media, and the Culture of Pornography; and Anyone You Want Me to Be: A True Story of Sex and Death on the Internet, coauthored with legendary FBI profiler John Douglas. Formerly a staff writer for the Denver Post, he lives in Denver. Visit his website at www.stephensingular.com.