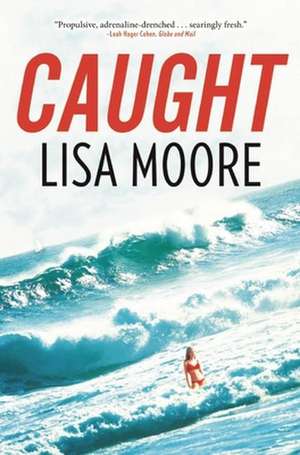

Caught

Autor Lisa Mooreen Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 ian 2015

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Scotiabank Giller Prize (2013), Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize (2013)

“Moore combines the propulsive storytelling of a beach-book thriller with the skilled use of language and penetrating insights of literary fiction. She pulls it off seamlessly, creating a vivid, compulsively readable tale.”—Penthouse

Shortlisted for the 2013 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize, Caught is a “propulsive, adrenalin-drenched” (Globe and Mail) novel from 2013 Writers’ Trust Engel/Findley Award winner Lisa Moore, which brilliantly captures a moment in the late 1970s before the almost folkloric glamour surrounding pot smuggling turned violent. Moore’s protagonist, David Slaney, is a modern Billy the Kid, a swaggering folk-hero-in-the making who busts out of prison to embark on one last great heist and win back the woman he loves. As Slaney makes his fugitive journey across Canada—tailed closely by a detective hell-bent on making an arrest—Slaney reignites passions with his old flame; tracks down his former drug smuggling partner; and adopts numerous guises to outpace authorities: hitchhiker, houseguest, student, and lover. Thrumming with energy and suspense, Caught is a thrillingly charged escapade from one of Canada’s most acclaimed writers.

“Outstanding . . . Surprising and superb . . . A literary adventure story . . . Gripping, detailed, and wholly convincing . . . A supremely human book . . . combining the complexity of the best literary fiction with the page-turning compulsive readability of a thriller.”—National Post

“A new kind of legend for a new Newfoundland.”—Reader's Digest

“Exhilarating… a memorably oddball and alluring novel that’s simultaneously breezy, taut, funny, and insightful.” —The Vancouver Sun

Shortlisted for the 2013 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize, Caught is a “propulsive, adrenalin-drenched” (Globe and Mail) novel from 2013 Writers’ Trust Engel/Findley Award winner Lisa Moore, which brilliantly captures a moment in the late 1970s before the almost folkloric glamour surrounding pot smuggling turned violent. Moore’s protagonist, David Slaney, is a modern Billy the Kid, a swaggering folk-hero-in-the making who busts out of prison to embark on one last great heist and win back the woman he loves. As Slaney makes his fugitive journey across Canada—tailed closely by a detective hell-bent on making an arrest—Slaney reignites passions with his old flame; tracks down his former drug smuggling partner; and adopts numerous guises to outpace authorities: hitchhiker, houseguest, student, and lover. Thrumming with energy and suspense, Caught is a thrillingly charged escapade from one of Canada’s most acclaimed writers.

“Outstanding . . . Surprising and superb . . . A literary adventure story . . . Gripping, detailed, and wholly convincing . . . A supremely human book . . . combining the complexity of the best literary fiction with the page-turning compulsive readability of a thriller.”—National Post

“A new kind of legend for a new Newfoundland.”—Reader's Digest

“Exhilarating… a memorably oddball and alluring novel that’s simultaneously breezy, taut, funny, and insightful.” —The Vancouver Sun

Preț: 60.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 91

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.67€ • 12.14$ • 9.63£

11.67€ • 12.14$ • 9.63£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780802122957

ISBN-10: 0802122957

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 137 x 206 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

ISBN-10: 0802122957

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 137 x 206 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Grove Atlantic

Notă biografică

Lisa Moore is the author of February, which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, selected as one of The New Yorker's Best Books of the Year, and was a Globe and Mail Top 100 Book; and Alligator, which was a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and won the Commonwealth Fiction Prize (Canada and the Caribbean), and was a Canadian bestseller.

Extras

Searchlight

Slaney broke out of the woods and skidded down a soft embankment to the side of the road. There was nothing but forest on both sides of the asphalt as far as he could see. He thought it might be three in the morning and he was about two miles from the prison. It had taken an hour to get through the woods.

He had crawled under the chain link fence around the yard and through the long grass on the other side. He had run hunched over and he’d crawled on his elbows and knees, pulling himself across the ground, and he’d stayed still, with his face in the earth, while the searchlight arced over him. At the end of the field was a steep hill of loose shale and the rocks had clattered away from his shoes. The soles of Slaney’s shoes were tan-coloured and slippery. The tan had worn off and a smooth patch of black rubber showed on the bottom of each shoe. He’d imagined the soles lit up as the searchlight hit them. He had on the orange coveralls. They had always been orange but when everybody was wearing them they were less orange.

For an instant the perfect oval of hard light had contained him like the shell of an egg and then he’d gone animal numb and cringing, a counter-intuitive move, the prison psychotherapist might have said, if they were back in her office discussing the break – she talked slips and displacement, sublimation and counter-intuition and allowed for an inner mechanism he could not see or touch but had to account for - then the oval slid him back into darkness and he charged up the hill again.

Near the top, the shale had given way to a curve of reddish topsoil with an overhang of long grass and shrub. There was a ringer washer turned on its side, a bald white, and a cracked yellow beef bucket.

Slaney had grabbed at a tangled clot of branches but it had come loose in his hand. Then he’d dug the toe of his shoe deep and found purchase and hefted his chest over the prickly grass overhang and rolled on top of it.

There he’d been, flat on his back, chest heaving, looking at the stars. It was as far as he had been from the Springhill Penitentiary since the doors of that institution admitted him four years before. It was not far enough. He’d heaved himself off the ground and started running.

This was Nova Scotia and it was June 14th,1978. Slaney would be twenty-five years old the very next day. The night of his escape would come back to him, moments of lit intensity, for the rest of his life. He saw himself on that hill in the brilliant spot of the swinging searchlight, the orange of his own back, as it might have appeared to the guards in the watchtower, had they glanced that way.

The Long Night

Slaney stood on the highway and the stillness of the moonlit night settled over him. The evening thumped down and Slaney ran for all he was worth because it seemed foolhardy to stand still.

Then it seemed foolhardy to not be still.

He felt he had to be still in order to listen. He was listening with all his might. He knew the squad cars were coming and there would be dogs. He accepted the unequivocal fact that there was nothing he could do now but wait. A fellow prisoner named Harold had arranged a place for him. It was a room over a bar, several hours from the penitenary, if Slaney happened to get that far. Harold said that the bar belonged to his grandmother. They had a horsehair dance floor and served the best fish and chips in Nova Scotia. They had rock bands passing through and strippers on the weekends and they sponsored a school basketball team.

Harold’s place was in Guysborough. The cops would be expecting Slaney to be going west. But Slaney was lighting out in the opposite direction. The trucker was heading for the ferry in North Sydney, bringing a shipment of Lay’s potato chips to Newfoundland.

Slaney could get a ride with him as far as Harold’s place in Guysborough, then backtrack the next day when things had cooled down a little. He bent over on the side of the highway with his hands on his knees and caught his breath. He whispered to himself. He spoke a stream of profanity and he said a prayer to the Virgin Mary in whom he half believed. Mosquitoes touched him all over. They settled on his skin and put their fine things into him and they were lulled and bloated and thought themselves sexy and near death.

They got in his mouth and he spit and they dotted his saliva. They were in the crease of his left eyelid. He wiped a mosquito out of his eye and found he was weeping. He was snot-smeared and tears dropped off his eyelashes. He could hear the whine of just one mosquito above the rest.

It was tears or sweat, he didn’t know.

He’d broken out of prison after four years and he was going back to Colombia. He’d learned from the first trip down there, the trip that had landed him in jail, that the most serious mistakes are the easiest to make. There are mistakes that stand in the centre of an empty field and cry out for love.

The largest mistake, that time, was that Slaney and Hearn had underestimated the Newfoundland fishermen of Capelin Cove. The fishermen had known about the caves the boys had dug for stashing the weed. They’d seen the guys with their long hair and shovels and picks drive in from town and set up tents in an empty field. They’d watched them down at the beach all day, heard them at night with their guitars around the bonfire. The fishermen had called the cops. Slaney and the boys had mistaken idle calculation for a blind eye and they had been turned in.

And they’d mistaken the fog for cover but it was an unveiling. Slaney and Hearn had lost their bearings in a dense fog, after sailing home from Colombia. They were just a half mile off shore with two tons of marijuana on board and they’d required assistance.

There were mistakes and there was a dearth of luck when they had needed just a little. A little luck would have seen them through the first trip despite their dumb moves.

Now Slaney was out again and he knew the nature of mistakes. They were detectable but you had to read all the signs backwards or inside out. Those first mistakes had cost him. They meant he could never go home. He’d never see Newfoundland again.

Everything will happen from here, he thought. This time they would do it right. He could feel luck like an animal presence, feral and watchful. He would have to coax it into the open. Grab it by the throat.

Slaney had broken out of prison and beat his way through the forest. He’d stumbled into a ditch of lupins. The searchlight must have seeped into his skin back there, just outside the prison fence, a radioactive buzz that left him with something extra. He wasn’t himself; he was himself with something added. Or the light had bleached away everything he was except the need to not be attacked by police dogs.

There was the scent of the lupins as he bashed through, the wet stalks grabbing at his shins. Cold raindrops scattering from the leaves. Then he was up on the shoulder of the road. He batted his hands around his head, girly swings at the swarms of mosquitoes.

The prayers he said between gusts of filthy language were polite and he had honed down his petition to a single word: the word was please. He had an idea about the Virgin Mary in ordinary clothes, jeans and a t-shirt. She was complicated but placid, more human than divine. He did not think virgin, he thought ordinary and smart. A girl with a blade of grass between her thumbs that she blew on to make a trilling noise. He called out for her now.

His prayers were meant to stave off the dread he felt and a shame that had nothing to do with the crime he’d committed or the fact that he was standing on the side of the road, under the moon, covered in mud, at the mercy of an ex convict with a transport truck.

It was a rootless and fickle shame. It might have been someone else’s shame, a storm touching down, or a shame belonging to no one, knocking against everything in its path.

His curses were an incantation against too much humility and the prayers pleaded with the Virgin to make the mosquitoes go away. Then the earth revved and thrummed. He jumped back into the ditch. He lay down flat with the lupins trembling over him. The sirens were loud, even at a distance, baritone whoops that scaled up to clear metallic bleats. The hoops of hollow, tin-bright noise overlapped and the torrent of squeal echoed off the hills. Slaney counted five cars. There were five of them.

Red and blue bands of light sliced through the lupin stalks and the heads of the flowers tipped and swung in the back draft as the cars roared past. The siren of each car was so shrill, as it swept past, that it pierced the bones of his skull and the tiny hammer in his ear banged out a message of calibrated terror and the rocks his cheek rested on in the ditch were full of vibration and then the sirens, one at a time, receded, and the echoes dissipated and silence followed. It was not silence. Slaney mistook it for silence but there was a wind that had come a long distance and it jostled every tree. Some branches rubbed against each other, squeaking. The leaves of the lupins chussled like the turning pages of a glossy magazine.

Five cars. They would go another three or four miles and then they’d let the dogs out. They had taken this long because they’d had to gather up the dogs. Slaney listened for the barking, which would be carried on the wind. He crawled out of the ditch to meet the next vehicle and he stood straight and brushed his hands over his chest and tugged the collar of the coveralls. He couldn’t wait for the truck that had been arranged. Anything could have happened to that truck.

He was getting the hell out of there before the dogs showed up. A station wagon went by with one headlight and he could see in the pale yellow shaft that it had begun to rain. The station wagon had a mattress tied to the roof. It had slowed to a crawl. There was a woman smoking a cigarette in the passenger seat. She turned all the way around to get a good look at him as they rolled to a stop. Slaney would remember her face for a long time. An amber dashlight lit her brown hair. The reflection of his own face slid over hers on the window and stopped when the car stopped, so that for the briefest instant, the two faces became one grotesque face with two noses and four eyes, and there was an elongated forehead and a stretched mannish chin under her full mouth and maybe she saw the same thing on her side of the glass.

The cop cars must have passed her already and she would have known that they were looking for someone. She exhaled the smoke and he saw it waggle up lazily. She reached over and touched the lock on the passenger door with a finger. They paused there, looking at him, though Slaney could not see the driver of the car, and then they’d sped up with a spray of gravel hitting his thighs.

Slaney broke out of the woods and skidded down a soft embankment to the side of the road. There was nothing but forest on both sides of the asphalt as far as he could see. He thought it might be three in the morning and he was about two miles from the prison. It had taken an hour to get through the woods.

He had crawled under the chain link fence around the yard and through the long grass on the other side. He had run hunched over and he’d crawled on his elbows and knees, pulling himself across the ground, and he’d stayed still, with his face in the earth, while the searchlight arced over him. At the end of the field was a steep hill of loose shale and the rocks had clattered away from his shoes. The soles of Slaney’s shoes were tan-coloured and slippery. The tan had worn off and a smooth patch of black rubber showed on the bottom of each shoe. He’d imagined the soles lit up as the searchlight hit them. He had on the orange coveralls. They had always been orange but when everybody was wearing them they were less orange.

For an instant the perfect oval of hard light had contained him like the shell of an egg and then he’d gone animal numb and cringing, a counter-intuitive move, the prison psychotherapist might have said, if they were back in her office discussing the break – she talked slips and displacement, sublimation and counter-intuition and allowed for an inner mechanism he could not see or touch but had to account for - then the oval slid him back into darkness and he charged up the hill again.

Near the top, the shale had given way to a curve of reddish topsoil with an overhang of long grass and shrub. There was a ringer washer turned on its side, a bald white, and a cracked yellow beef bucket.

Slaney had grabbed at a tangled clot of branches but it had come loose in his hand. Then he’d dug the toe of his shoe deep and found purchase and hefted his chest over the prickly grass overhang and rolled on top of it.

There he’d been, flat on his back, chest heaving, looking at the stars. It was as far as he had been from the Springhill Penitentiary since the doors of that institution admitted him four years before. It was not far enough. He’d heaved himself off the ground and started running.

This was Nova Scotia and it was June 14th,1978. Slaney would be twenty-five years old the very next day. The night of his escape would come back to him, moments of lit intensity, for the rest of his life. He saw himself on that hill in the brilliant spot of the swinging searchlight, the orange of his own back, as it might have appeared to the guards in the watchtower, had they glanced that way.

The Long Night

Slaney stood on the highway and the stillness of the moonlit night settled over him. The evening thumped down and Slaney ran for all he was worth because it seemed foolhardy to stand still.

Then it seemed foolhardy to not be still.

He felt he had to be still in order to listen. He was listening with all his might. He knew the squad cars were coming and there would be dogs. He accepted the unequivocal fact that there was nothing he could do now but wait. A fellow prisoner named Harold had arranged a place for him. It was a room over a bar, several hours from the penitenary, if Slaney happened to get that far. Harold said that the bar belonged to his grandmother. They had a horsehair dance floor and served the best fish and chips in Nova Scotia. They had rock bands passing through and strippers on the weekends and they sponsored a school basketball team.

Harold’s place was in Guysborough. The cops would be expecting Slaney to be going west. But Slaney was lighting out in the opposite direction. The trucker was heading for the ferry in North Sydney, bringing a shipment of Lay’s potato chips to Newfoundland.

Slaney could get a ride with him as far as Harold’s place in Guysborough, then backtrack the next day when things had cooled down a little. He bent over on the side of the highway with his hands on his knees and caught his breath. He whispered to himself. He spoke a stream of profanity and he said a prayer to the Virgin Mary in whom he half believed. Mosquitoes touched him all over. They settled on his skin and put their fine things into him and they were lulled and bloated and thought themselves sexy and near death.

They got in his mouth and he spit and they dotted his saliva. They were in the crease of his left eyelid. He wiped a mosquito out of his eye and found he was weeping. He was snot-smeared and tears dropped off his eyelashes. He could hear the whine of just one mosquito above the rest.

It was tears or sweat, he didn’t know.

He’d broken out of prison after four years and he was going back to Colombia. He’d learned from the first trip down there, the trip that had landed him in jail, that the most serious mistakes are the easiest to make. There are mistakes that stand in the centre of an empty field and cry out for love.

The largest mistake, that time, was that Slaney and Hearn had underestimated the Newfoundland fishermen of Capelin Cove. The fishermen had known about the caves the boys had dug for stashing the weed. They’d seen the guys with their long hair and shovels and picks drive in from town and set up tents in an empty field. They’d watched them down at the beach all day, heard them at night with their guitars around the bonfire. The fishermen had called the cops. Slaney and the boys had mistaken idle calculation for a blind eye and they had been turned in.

And they’d mistaken the fog for cover but it was an unveiling. Slaney and Hearn had lost their bearings in a dense fog, after sailing home from Colombia. They were just a half mile off shore with two tons of marijuana on board and they’d required assistance.

There were mistakes and there was a dearth of luck when they had needed just a little. A little luck would have seen them through the first trip despite their dumb moves.

Now Slaney was out again and he knew the nature of mistakes. They were detectable but you had to read all the signs backwards or inside out. Those first mistakes had cost him. They meant he could never go home. He’d never see Newfoundland again.

Everything will happen from here, he thought. This time they would do it right. He could feel luck like an animal presence, feral and watchful. He would have to coax it into the open. Grab it by the throat.

Slaney had broken out of prison and beat his way through the forest. He’d stumbled into a ditch of lupins. The searchlight must have seeped into his skin back there, just outside the prison fence, a radioactive buzz that left him with something extra. He wasn’t himself; he was himself with something added. Or the light had bleached away everything he was except the need to not be attacked by police dogs.

There was the scent of the lupins as he bashed through, the wet stalks grabbing at his shins. Cold raindrops scattering from the leaves. Then he was up on the shoulder of the road. He batted his hands around his head, girly swings at the swarms of mosquitoes.

The prayers he said between gusts of filthy language were polite and he had honed down his petition to a single word: the word was please. He had an idea about the Virgin Mary in ordinary clothes, jeans and a t-shirt. She was complicated but placid, more human than divine. He did not think virgin, he thought ordinary and smart. A girl with a blade of grass between her thumbs that she blew on to make a trilling noise. He called out for her now.

His prayers were meant to stave off the dread he felt and a shame that had nothing to do with the crime he’d committed or the fact that he was standing on the side of the road, under the moon, covered in mud, at the mercy of an ex convict with a transport truck.

It was a rootless and fickle shame. It might have been someone else’s shame, a storm touching down, or a shame belonging to no one, knocking against everything in its path.

His curses were an incantation against too much humility and the prayers pleaded with the Virgin to make the mosquitoes go away. Then the earth revved and thrummed. He jumped back into the ditch. He lay down flat with the lupins trembling over him. The sirens were loud, even at a distance, baritone whoops that scaled up to clear metallic bleats. The hoops of hollow, tin-bright noise overlapped and the torrent of squeal echoed off the hills. Slaney counted five cars. There were five of them.

Red and blue bands of light sliced through the lupin stalks and the heads of the flowers tipped and swung in the back draft as the cars roared past. The siren of each car was so shrill, as it swept past, that it pierced the bones of his skull and the tiny hammer in his ear banged out a message of calibrated terror and the rocks his cheek rested on in the ditch were full of vibration and then the sirens, one at a time, receded, and the echoes dissipated and silence followed. It was not silence. Slaney mistook it for silence but there was a wind that had come a long distance and it jostled every tree. Some branches rubbed against each other, squeaking. The leaves of the lupins chussled like the turning pages of a glossy magazine.

Five cars. They would go another three or four miles and then they’d let the dogs out. They had taken this long because they’d had to gather up the dogs. Slaney listened for the barking, which would be carried on the wind. He crawled out of the ditch to meet the next vehicle and he stood straight and brushed his hands over his chest and tugged the collar of the coveralls. He couldn’t wait for the truck that had been arranged. Anything could have happened to that truck.

He was getting the hell out of there before the dogs showed up. A station wagon went by with one headlight and he could see in the pale yellow shaft that it had begun to rain. The station wagon had a mattress tied to the roof. It had slowed to a crawl. There was a woman smoking a cigarette in the passenger seat. She turned all the way around to get a good look at him as they rolled to a stop. Slaney would remember her face for a long time. An amber dashlight lit her brown hair. The reflection of his own face slid over hers on the window and stopped when the car stopped, so that for the briefest instant, the two faces became one grotesque face with two noses and four eyes, and there was an elongated forehead and a stretched mannish chin under her full mouth and maybe she saw the same thing on her side of the glass.

The cop cars must have passed her already and she would have known that they were looking for someone. She exhaled the smoke and he saw it waggle up lazily. She reached over and touched the lock on the passenger door with a finger. They paused there, looking at him, though Slaney could not see the driver of the car, and then they’d sped up with a spray of gravel hitting his thighs.

Premii

- Scotiabank Giller Prize Finalist, 2013

- Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize Finalist, 2013