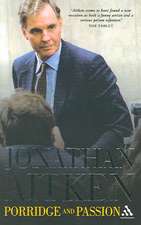

Charles W. Colson

Autor Jonathan Aitken, Aitkenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2005

Charles Colson has become one of the most revered leaders of our time. His ministry outreach, Prison Fellowship, has swelled to 40,000 volunteers working in 100 countries. His Angel Tree Christmas program provides presents to more than half a million children of prison inmates every year. His daily radio broadcast, BreakPoint, airs daily on more than 1,000 radio outlets across the country. And his twenty books have sold more than five million copies in the U.S.

But God had to work some mighty miracles to bring this unusual servant to this prominent place of service. After all, Colson was known as President Nixon’s “hatchet man.” His involvement in the Watergate conspiracy led him to prisonߝand then to a life-changing encounter with God.

Now, noted author Jonathan Aitken has written the first biography that compellingly presents a first-rate understanding of the political, historical, and spiritual journeys of Charles W. Colson… a life redeemed.

Preț: 111.91 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.41€ • 22.42$ • 17.76£

21.41€ • 22.42$ • 17.76£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 09-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400072194

ISBN-10: 1400072190

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

ISBN-10: 1400072190

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 156 x 234 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: Waterbrook Press

Notă biografică

JONATHAN AITKEN, an Oxford graduate in both law and theology, is the author of the award-winning biography Nixon: A Life. A former British M.P. and cabinet member, his political career ended in 1999 when he served a seven-month prison term for perjury in a civil case. He is now a lecturer, author, columnist, and broadcaster.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

An Unsettled Upbringing

Parents and Childhood

In the beginning was the energy, a life force so enthusiastic that everyone noticed him as a boy with leadership qualities, who never did things by halves, and who rarely knew when to stop. Whether it was collecting nickels and dimes for the war effort, selling ads for the school magazine, or playing practical jokes on his friends, he had exceptional drive that combined zeal, ingenuity, and humor. Yet the levitas in his nature was balanced by a gravitas shown in the self-discipline he applied to achieving the academic goals of his schoolboy years. So even in his earliest days there were intriguingly polarized characteristics in the young Charles Colson. It did not need an expert in genetics to deduce that they flowed from his radically different parents.

No mother could have had a more appropriate nickname than Dizzy Colson. The nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, who acquired the same sobriquet, coined a phrase to describe his parliamentary opponent William Gladstone: "Inebriated by the exuberance of his own verbosity." It was a cap that would have fit well on Inez Ducrow Colson. For Dizzy Colson was a twentieth-century American eccentric who never stopped talking, showing off, spending money, or striking attitudes that she hoped would shock her friends and relatives. Colorful anecdotes of Dizzy abound throughout the story of her son's life.

When Dizzy made her first visit to the White House in 1969 to see Charlie, as she always called her son, in his office as special counsel to the president, she was unusually dressed for the occasion. She wore a light overcoat, but beneath it she was clad in nothing more than her underwear and a slip. When she explained to a startled cousin how she justified this bizarre ensemble, Dizzy declared: "But no one ever lets you take off your topcoat in the White House!" History does not record whether Mrs. Colson ever tested her theory of the disrobing customs at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in the Nixon years or whether she simply invented the story to shock her straitlaced relative. The latter seems more likely since Dizzy was not given to understatement either in dress or in words.

One post-White House occasion when Dizzy might have found it difficult to overstate her own role in the proceedings was the Washington movie premiere of the film of her son's best-selling autobiography, Born Again. Surrounded by Hollywood stars, Beltway celebrities, the sister of the president of the United States, and a theater full of heavyweight figures from the worlds of politics, journalism, and religion, most mothers might have been content to bask in reflected glory from a backseat. Not Dizzy. Although she was under strict instructions not to talk to the press and had even been assigned a minder to ensure her silence, Inez Ducrow Colson was not one to hide her light under a bushel. She escaped from her minder, Mrs. Beth Loux, by slipping into a stall in the ladies' rest room and slipping out again underneath one of the partitions separating the toilets. By the time Mrs. Loux had discovered that her charge had bolted even though her toilet door was still closed, Dizzy was in full flow, giving an interview to the style correspondent of the Washington Post. The main feature of the interview was Mrs. Colson's ethically incorrect opinion of her son's role in Watergate and of his efforts to blacken the character of Daniel Ellsberg. "I'm proud of what Chuck tried to do to that communist Ellsberg. . . . I wish he would get up and say, 'I'm proud.' . . . I never want to hear Chuck saying, 'I'm sorry,'" she declared. Apparently oblivious to the new Colson message of Christian contrition and change, Dizzy professed to be mystified by the book's title. "I born him first. I had him baptized as a baby. I don't understand this 'Born Again' business," she told reporters.

It was not the first or last time that Charles Colson found himself at loggerheads with his mother. "The problem was that he and Dizzy banged smack into the middle of each other's energy fields," was how one member of the family summarized their turbulent relationship. The collisions between filial chalk and maternal cheese sometimes had awkward consequences. With the looks of a Bette Davis and the effervescence of a Goldie Hawn, Dizzy had a flamboyance in her character that was the antithesis of her son's self-discipline. Immensely attractive in her expansive personality, she combined generosity of spirit toward underdogs with financial recklessness about overdrafts. One of her many iron whims was a determination to be on the move. This included house moves, for in the 1930s and 1940s the Colsons had at least fifteen different addresses in the Boston area, a velocity of change that caused young Charlie to attend eight schools before reaching the age of twelve.

Some of this switching of abodes may have been due to Dizzy's peripatetic restlessness of spirit, but the more fundamental cause was the constant fluctuation of the family finances. These cash flow problems were usually caused by Dizzy's chronic overspending on clothes, flowers, furniture, and household decorations--of which only the very best would do. Some of Charles Colson's most painful childhood memories concerned the aftereffects of his mother's extravagance, when forced sales of the family furniture were required because her bills had mounted too high. The shock of coming home from school and finding complete strangers carrying chairs out of the living room left its scars on the adolescent Colson. The anxieties created by the debt crises and rent shortfalls of his youth resulted in a careful frugality with money in his adult life.

Visits from debt collectors were not the only insecurities to trouble young Charlie. Another perplexity was his mother's sense of humor. Extraordinary though it sounds, Dizzy enjoyed pretending that her son was not her son at all. With a straight face she would tell her friends that she had really given birth to a daughter, who had been accidentally swapped by a maternity nurse in the hospital for the boy baby she now had to bring up. So elaborate were the details of this fantasy that some people actually believed it. Although Charlie himself was not among the believers, he was understandably unsettled by the frequency with which his mother repeated and varied the story in ways that could only have been hurtful to a young boy. As he recalled it: "This was my mother's favorite gag. Of course, I knew she was saying it half in humor, but it always left me feeling uncomfortable. Even to me she would say, 'I never wanted a boy. I really wanted a little girl and I had one.' Then she'd go on and explain how in the next room in the hospital there'd been a Mrs. Peterson who'd had a girl and that the hospital had mixed up the babies. 'So you really belong to Mrs. Peterson and her little girl is really my daughter,' she used to say."

A modern child psychologist might make interesting observations on the wisdom of these maternal jests, particularly since their negative impact was compounded by Dizzy's reluctance to express the love and pride she inwardly felt for her Charlie. These failings corrected themselves when she spoke of him with loving admiration to other people. Yet the direct lines of communication between mother and son were curiously flawed, as the latter recalls: "My mother would never say to me, 'I am really proud of you and what you're doing.' She never said, 'You're wonderful,' or, 'I love you.' I can't ever recall my mother saying things like that to me . . . she never really understood me or my work . . . we just never clicked."

Fortunately for the young Charles Colson, he clicked happily with his other parent, his father, Wendell Ball Colson, with whom he had a good rapport and many similarities of both character and appearance.

The Colsons came from Scandinavian stock. Wendell's father arrived in America in the 1870s as an immigrant from Sweden. He became a successful musician, celebrated for his cornet solos with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but his life and career were ended by a virulent flu epidemic in 1919. Wendell was seventeen at the time of his father's death and he dropped out of high school in order to support his widowed mother. Throughout his remaining teens and twenties, Wendell worked as a bookkeeper for a Boston meatpacking plant, earning around $32 a week. However, he was determined to better himself, for he spent his evenings studying at night school until, after twelve years, he achieved professional qualifications in law and accountancy.

In the middle of these exertions Wendell met the colorful Inez, or Dizzy, Ducrow, a beautiful twenty-one-year-old Bostonian whose penchant for fantasy extended to the claim that she was descended from the British aristocracy. The British part was true. Her parents emigrated from Birmingham, England, in about 1900 and never relinquished their U.K. citizenship, even though they resided in the United States for over forty years. Aristocratic lineage would have been harder to establish, for Dizzy's father was a silversmith, a trade that in nineteenth-century Britain was not usually associated with the nobility and gentry unless they were its customers.

The marriage of Wendell Colson and Inez Ducrow at Saint Andrew's Episcopal Church, Orient Heights, in 1926, seems to have been inspired by that random arrow of Cupid known as "the attraction of opposites." In temperament and behavior, the bride and groom were poles apart, but perhaps Dizzy's intuition told her that she needed the qualities of stolidity and stability in a husband. Although Wendell must occasionally have wondered whether his down-to-earth normality was equal to the task of keeping his exotic wife rooted in reality, their forty-eight-year marriage was a happy one. Despite those creative fictions about the mix-up with Mrs. Peterson's daughter in the maternity ward, one of the most joyful moments of the marriage must surely have been the birth of their only child, Charles Wendell Colson, on October 16, 1931. To be born during the years of the Depression in one of North Boston's poorer residential districts meant growing up in an environment tinged by economic hardship and food shortages. Although the Colsons never went hungry, because Wendell held down a steady job in the food industry throughout the Depression, many of their neighbors were not so fortunate. One of Charlie's earliest memories was of his mother cooking subsistence meals for people down the street who had nothing to eat, and of giving away her best coats to unemployed women who were cold in winter.

Wartime memories also loomed large in the Colson boyhood. He was ten years old when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and he remembers how fear stalked the streets of Boston in 1942-43 over expected Japanese or German bombing raids and submarine attacks. His father was appointed an air raid warden with the duty of going out on night patrol to check that everyone in the neighborhood had put blackout curtains over their windows so that enemy pilots could not see any lights on the ground. Charlie himself contributed to the war effort at the age of eleven, when he organized a schoolboy house-to-house collection to buy a jeep for the U.S. Army. As the leader of this fund-raising campaign, Charlie sold his model aircraft collection to swell the coffers, and was chosen to hand over the check to an army officer--an event recorded for posterity by a photograph published in the Boston Globe.

Also recorded for posterity was an early example of Colson's talent for public speaking and fund-raising. In the course of the campaign for collecting donations to the jeep fund, Charlie addressed his fellow sixth-grade classmates with a speech whose pencil-written text has survived in his family archives. "What I am about to say I want to be assured as a plea not as an offer," began the eleven-year-old orator. "There will be no reward for your donations and work, nothing but the satisfaction of knowing that you are helping our boys. . .

"The war now rests on the shoulders of the American people. If the people of the conquered countries had another chance they would gladly give their money, their homes, yes, even their lives. We, the people of the United States, are the avenging sword of freedom destined to liberate the impressed [sic] world. This can be our destiny if we give this cause our fullest cooperation."

Although a little flamboyant for an audience of ten- and eleven-year-old schoolboys, Colson's first speech displayed some early promise of political leadership. It also revealed some early skills in the art of news management, since a version of the text appeared in the Boston Herald. Even to have attempted such an address while in sixth grade suggests a certain precociousness. This may have stemmed from the self-assurance that came from his overprotected home life as an only child. The privations of the Depression followed by the uncertainties and food rationing of the war were the ostensible reasons why Dizzy did not have any more babies. Her decision may also have been influenced by the exceptional pain she suffered in childbirth from her son's high forceps delivery. Like many an offspring without siblings, Charlie was cosseted by his parents. Yet his mother's cosseting seemed negative because she was excessively critical and overbearing in her maternal attentions. By contrast, his father was a more positive source of support and encouragement. Described by a contemporary as "the straightest of straight arrows . . . a lovable, kind old bear of a man with a wonderfully calm and easygoing tolerance which he sure needed to cope with Diz," Wendell was the rock on which his son's character was built. For Chuck, as his father preferred to call him, absorbed his core values from his dad and regarded him as a role model of diligence, dedication to the job, and patriotic duty.

In spite of the paternal emphasis on these values, Chuck grew up with a well-tuned appreciation of the absurd. Both his parents had a keen sense of humor, especially Wendell, who loved playing practical jokes within the family. This was a peculiarity that Chuck inherited. His boyhood was packed with slapstick episodes, such as letting off stink bombs in movie theaters, pulling away the legs of the hall table in a country club in order to leave a hapless cousin holding an unsupported surface laden with silverware, and hiding snowballs in the caps of train drivers. This humorous activity went deeper than the syndrome of "Boys will be boys," for as later chapters will show, Chuck's penchant for juvenile capers lasted long into adulthood. The child that was father to the man had a strong streak of comic, as well as serious, energy within him.

Perhaps the most serious legacy of his childhood was a reverence for academic achievement. Chuck was deeply impressed, when he was eight years old, at going to watch his father receive his degree from Northeastern Law School, formally dressed in gown and mortarboard. That graduation ceremony, and the long hours at night school he knew had preceded it, imprinted on Chuck a highly developed sense of the importance of education.

An Unsettled Upbringing

Parents and Childhood

In the beginning was the energy, a life force so enthusiastic that everyone noticed him as a boy with leadership qualities, who never did things by halves, and who rarely knew when to stop. Whether it was collecting nickels and dimes for the war effort, selling ads for the school magazine, or playing practical jokes on his friends, he had exceptional drive that combined zeal, ingenuity, and humor. Yet the levitas in his nature was balanced by a gravitas shown in the self-discipline he applied to achieving the academic goals of his schoolboy years. So even in his earliest days there were intriguingly polarized characteristics in the young Charles Colson. It did not need an expert in genetics to deduce that they flowed from his radically different parents.

No mother could have had a more appropriate nickname than Dizzy Colson. The nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, who acquired the same sobriquet, coined a phrase to describe his parliamentary opponent William Gladstone: "Inebriated by the exuberance of his own verbosity." It was a cap that would have fit well on Inez Ducrow Colson. For Dizzy Colson was a twentieth-century American eccentric who never stopped talking, showing off, spending money, or striking attitudes that she hoped would shock her friends and relatives. Colorful anecdotes of Dizzy abound throughout the story of her son's life.

When Dizzy made her first visit to the White House in 1969 to see Charlie, as she always called her son, in his office as special counsel to the president, she was unusually dressed for the occasion. She wore a light overcoat, but beneath it she was clad in nothing more than her underwear and a slip. When she explained to a startled cousin how she justified this bizarre ensemble, Dizzy declared: "But no one ever lets you take off your topcoat in the White House!" History does not record whether Mrs. Colson ever tested her theory of the disrobing customs at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in the Nixon years or whether she simply invented the story to shock her straitlaced relative. The latter seems more likely since Dizzy was not given to understatement either in dress or in words.

One post-White House occasion when Dizzy might have found it difficult to overstate her own role in the proceedings was the Washington movie premiere of the film of her son's best-selling autobiography, Born Again. Surrounded by Hollywood stars, Beltway celebrities, the sister of the president of the United States, and a theater full of heavyweight figures from the worlds of politics, journalism, and religion, most mothers might have been content to bask in reflected glory from a backseat. Not Dizzy. Although she was under strict instructions not to talk to the press and had even been assigned a minder to ensure her silence, Inez Ducrow Colson was not one to hide her light under a bushel. She escaped from her minder, Mrs. Beth Loux, by slipping into a stall in the ladies' rest room and slipping out again underneath one of the partitions separating the toilets. By the time Mrs. Loux had discovered that her charge had bolted even though her toilet door was still closed, Dizzy was in full flow, giving an interview to the style correspondent of the Washington Post. The main feature of the interview was Mrs. Colson's ethically incorrect opinion of her son's role in Watergate and of his efforts to blacken the character of Daniel Ellsberg. "I'm proud of what Chuck tried to do to that communist Ellsberg. . . . I wish he would get up and say, 'I'm proud.' . . . I never want to hear Chuck saying, 'I'm sorry,'" she declared. Apparently oblivious to the new Colson message of Christian contrition and change, Dizzy professed to be mystified by the book's title. "I born him first. I had him baptized as a baby. I don't understand this 'Born Again' business," she told reporters.

It was not the first or last time that Charles Colson found himself at loggerheads with his mother. "The problem was that he and Dizzy banged smack into the middle of each other's energy fields," was how one member of the family summarized their turbulent relationship. The collisions between filial chalk and maternal cheese sometimes had awkward consequences. With the looks of a Bette Davis and the effervescence of a Goldie Hawn, Dizzy had a flamboyance in her character that was the antithesis of her son's self-discipline. Immensely attractive in her expansive personality, she combined generosity of spirit toward underdogs with financial recklessness about overdrafts. One of her many iron whims was a determination to be on the move. This included house moves, for in the 1930s and 1940s the Colsons had at least fifteen different addresses in the Boston area, a velocity of change that caused young Charlie to attend eight schools before reaching the age of twelve.

Some of this switching of abodes may have been due to Dizzy's peripatetic restlessness of spirit, but the more fundamental cause was the constant fluctuation of the family finances. These cash flow problems were usually caused by Dizzy's chronic overspending on clothes, flowers, furniture, and household decorations--of which only the very best would do. Some of Charles Colson's most painful childhood memories concerned the aftereffects of his mother's extravagance, when forced sales of the family furniture were required because her bills had mounted too high. The shock of coming home from school and finding complete strangers carrying chairs out of the living room left its scars on the adolescent Colson. The anxieties created by the debt crises and rent shortfalls of his youth resulted in a careful frugality with money in his adult life.

Visits from debt collectors were not the only insecurities to trouble young Charlie. Another perplexity was his mother's sense of humor. Extraordinary though it sounds, Dizzy enjoyed pretending that her son was not her son at all. With a straight face she would tell her friends that she had really given birth to a daughter, who had been accidentally swapped by a maternity nurse in the hospital for the boy baby she now had to bring up. So elaborate were the details of this fantasy that some people actually believed it. Although Charlie himself was not among the believers, he was understandably unsettled by the frequency with which his mother repeated and varied the story in ways that could only have been hurtful to a young boy. As he recalled it: "This was my mother's favorite gag. Of course, I knew she was saying it half in humor, but it always left me feeling uncomfortable. Even to me she would say, 'I never wanted a boy. I really wanted a little girl and I had one.' Then she'd go on and explain how in the next room in the hospital there'd been a Mrs. Peterson who'd had a girl and that the hospital had mixed up the babies. 'So you really belong to Mrs. Peterson and her little girl is really my daughter,' she used to say."

A modern child psychologist might make interesting observations on the wisdom of these maternal jests, particularly since their negative impact was compounded by Dizzy's reluctance to express the love and pride she inwardly felt for her Charlie. These failings corrected themselves when she spoke of him with loving admiration to other people. Yet the direct lines of communication between mother and son were curiously flawed, as the latter recalls: "My mother would never say to me, 'I am really proud of you and what you're doing.' She never said, 'You're wonderful,' or, 'I love you.' I can't ever recall my mother saying things like that to me . . . she never really understood me or my work . . . we just never clicked."

Fortunately for the young Charles Colson, he clicked happily with his other parent, his father, Wendell Ball Colson, with whom he had a good rapport and many similarities of both character and appearance.

The Colsons came from Scandinavian stock. Wendell's father arrived in America in the 1870s as an immigrant from Sweden. He became a successful musician, celebrated for his cornet solos with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but his life and career were ended by a virulent flu epidemic in 1919. Wendell was seventeen at the time of his father's death and he dropped out of high school in order to support his widowed mother. Throughout his remaining teens and twenties, Wendell worked as a bookkeeper for a Boston meatpacking plant, earning around $32 a week. However, he was determined to better himself, for he spent his evenings studying at night school until, after twelve years, he achieved professional qualifications in law and accountancy.

In the middle of these exertions Wendell met the colorful Inez, or Dizzy, Ducrow, a beautiful twenty-one-year-old Bostonian whose penchant for fantasy extended to the claim that she was descended from the British aristocracy. The British part was true. Her parents emigrated from Birmingham, England, in about 1900 and never relinquished their U.K. citizenship, even though they resided in the United States for over forty years. Aristocratic lineage would have been harder to establish, for Dizzy's father was a silversmith, a trade that in nineteenth-century Britain was not usually associated with the nobility and gentry unless they were its customers.

The marriage of Wendell Colson and Inez Ducrow at Saint Andrew's Episcopal Church, Orient Heights, in 1926, seems to have been inspired by that random arrow of Cupid known as "the attraction of opposites." In temperament and behavior, the bride and groom were poles apart, but perhaps Dizzy's intuition told her that she needed the qualities of stolidity and stability in a husband. Although Wendell must occasionally have wondered whether his down-to-earth normality was equal to the task of keeping his exotic wife rooted in reality, their forty-eight-year marriage was a happy one. Despite those creative fictions about the mix-up with Mrs. Peterson's daughter in the maternity ward, one of the most joyful moments of the marriage must surely have been the birth of their only child, Charles Wendell Colson, on October 16, 1931. To be born during the years of the Depression in one of North Boston's poorer residential districts meant growing up in an environment tinged by economic hardship and food shortages. Although the Colsons never went hungry, because Wendell held down a steady job in the food industry throughout the Depression, many of their neighbors were not so fortunate. One of Charlie's earliest memories was of his mother cooking subsistence meals for people down the street who had nothing to eat, and of giving away her best coats to unemployed women who were cold in winter.

Wartime memories also loomed large in the Colson boyhood. He was ten years old when Pearl Harbor was attacked, and he remembers how fear stalked the streets of Boston in 1942-43 over expected Japanese or German bombing raids and submarine attacks. His father was appointed an air raid warden with the duty of going out on night patrol to check that everyone in the neighborhood had put blackout curtains over their windows so that enemy pilots could not see any lights on the ground. Charlie himself contributed to the war effort at the age of eleven, when he organized a schoolboy house-to-house collection to buy a jeep for the U.S. Army. As the leader of this fund-raising campaign, Charlie sold his model aircraft collection to swell the coffers, and was chosen to hand over the check to an army officer--an event recorded for posterity by a photograph published in the Boston Globe.

Also recorded for posterity was an early example of Colson's talent for public speaking and fund-raising. In the course of the campaign for collecting donations to the jeep fund, Charlie addressed his fellow sixth-grade classmates with a speech whose pencil-written text has survived in his family archives. "What I am about to say I want to be assured as a plea not as an offer," began the eleven-year-old orator. "There will be no reward for your donations and work, nothing but the satisfaction of knowing that you are helping our boys. . .

"The war now rests on the shoulders of the American people. If the people of the conquered countries had another chance they would gladly give their money, their homes, yes, even their lives. We, the people of the United States, are the avenging sword of freedom destined to liberate the impressed [sic] world. This can be our destiny if we give this cause our fullest cooperation."

Although a little flamboyant for an audience of ten- and eleven-year-old schoolboys, Colson's first speech displayed some early promise of political leadership. It also revealed some early skills in the art of news management, since a version of the text appeared in the Boston Herald. Even to have attempted such an address while in sixth grade suggests a certain precociousness. This may have stemmed from the self-assurance that came from his overprotected home life as an only child. The privations of the Depression followed by the uncertainties and food rationing of the war were the ostensible reasons why Dizzy did not have any more babies. Her decision may also have been influenced by the exceptional pain she suffered in childbirth from her son's high forceps delivery. Like many an offspring without siblings, Charlie was cosseted by his parents. Yet his mother's cosseting seemed negative because she was excessively critical and overbearing in her maternal attentions. By contrast, his father was a more positive source of support and encouragement. Described by a contemporary as "the straightest of straight arrows . . . a lovable, kind old bear of a man with a wonderfully calm and easygoing tolerance which he sure needed to cope with Diz," Wendell was the rock on which his son's character was built. For Chuck, as his father preferred to call him, absorbed his core values from his dad and regarded him as a role model of diligence, dedication to the job, and patriotic duty.

In spite of the paternal emphasis on these values, Chuck grew up with a well-tuned appreciation of the absurd. Both his parents had a keen sense of humor, especially Wendell, who loved playing practical jokes within the family. This was a peculiarity that Chuck inherited. His boyhood was packed with slapstick episodes, such as letting off stink bombs in movie theaters, pulling away the legs of the hall table in a country club in order to leave a hapless cousin holding an unsupported surface laden with silverware, and hiding snowballs in the caps of train drivers. This humorous activity went deeper than the syndrome of "Boys will be boys," for as later chapters will show, Chuck's penchant for juvenile capers lasted long into adulthood. The child that was father to the man had a strong streak of comic, as well as serious, energy within him.

Perhaps the most serious legacy of his childhood was a reverence for academic achievement. Chuck was deeply impressed, when he was eight years old, at going to watch his father receive his degree from Northeastern Law School, formally dressed in gown and mortarboard. That graduation ceremony, and the long hours at night school he knew had preceded it, imprinted on Chuck a highly developed sense of the importance of education.

Recenzii

Praise for Jonathan Aitken’s Nixon: A Life

“Aitken’s well-wrought biography achieves the difficult task of adding hundreds of brush strokes to the existing portraits of Richard Nixon.”

—Washington Post

“Readers all across the political spectrum will reach for Aitken’s effective, interest-sustaining narrative.”

—Booklist

“Aitken has unearthed a treasure trove of insights via letters and other communications. A human, if flawed, Nixon emerges from this fascinating account, which could not be more highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

“Aitken’s well-wrought biography achieves the difficult task of adding hundreds of brush strokes to the existing portraits of Richard Nixon.”

—Washington Post

“Readers all across the political spectrum will reach for Aitken’s effective, interest-sustaining narrative.”

—Booklist

“Aitken has unearthed a treasure trove of insights via letters and other communications. A human, if flawed, Nixon emerges from this fascinating account, which could not be more highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

Descriere

The first of its kind, this biography compellingly presents a first-rate understanding of the political, historical, and spiritual journeys of Charles W. Colson.