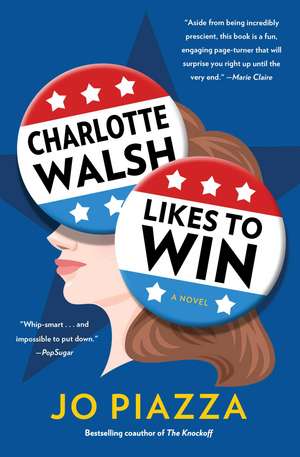

Charlotte Walsh Likes To Win

Autor Jo Piazzaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 mai 2021

Charlotte Walsh is running for Senate in the most important race in the country during a midterm election that will decide the balance of power in Congress. Reeling from a presidential election that shocked and divided the country and inspired to make a difference, she’s left her high-powered job in Silicon Valley and returned, with her husband and three young daughters, to her downtrodden Pennsylvania hometown to run for office in the Rust Belt state.

Once the campaign gets underway, Charlotte is blindsided by just how dirty her opponent is willing to fight, how harshly she is judged by the press and her peers, and how exhausting it becomes to navigate a marriage with an increasingly ambivalent and often resentful husband. When the opposition uncovers a secret that could threaten not just her campaign but everything Charlotte holds dear, she must decide just how badly she wants to win and at what cost.

“The essential political novel for the 2018 midterms” (Salon), Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win is an insightful portrait of what it takes for a woman to run for national office in America today. In a dramatic political moment like no other with more women running for office than ever before, this searing, suspenseful story of political ambition, marriage, class, sexual politics, and infidelity is timely, engrossing, and perfect for readers on both sides of the aisle.

Preț: 105.14 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.12€ • 20.93$ • 16.61£

20.12€ • 20.93$ • 16.61£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501179433

ISBN-10: 1501179438

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1501179438

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Jo Piazza is a bestselling author, podcast creator, and award-winning journalist. She is the national and international bestselling author of many critically acclaimed novels and nonfiction books including We Are Not Like Them, Charlotte Walsh Likes to Win, The Knockoff, and How to Be Married. Her work has been published in ten languages in twelve countries and four of her books have been optioned for film and television. A former editor, columnist, and travel writer with Yahoo, Current TV, and the Daily News (New York), her work has also appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, New York magazine, Glamour, Elle, Time, Marie Claire, The Daily Beast, and Slate. She holds an undergraduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania in economics and communication, a master’s in journalism from Columbia University, and a master’s in religious studies from New York University.

Extras

Charlotte Walsh Likes To Win

Tell people one true thing before you tell them a lie. Then it will be easier for them to believe the lie.

It wasn’t the best advice Marty Walsh ever gave to his daughter Charlotte, but it had stuck with her for almost forty years. Marty had been a garbage collector by trade, though he insisted “sanitation specialist” had a smarter ring to it. He wasn’t a successful man by most people’s standards and he died drunk in his bed before his fiftieth birthday. Now his daughter was running for the United States Senate and Marty’s words held a new utility for her.

Charlotte hadn’t expected her campaign to begin with an interrogation—an aggressive one at that—but the questions just kept coming.

“Have you ever used any drugs besides pot?”

“No.”

“Paid any undocumented workers under the table?”

“Nope.”

“Ever killed anyone?”

“Not yet.”

“Ever get an abortion?”

“No.”

“Infidelity in your marriage? Affairs? Secret ex-husband?”

“I love my husband. We don’t have anything to hide.” One of those things is true. Charlotte punctuated her sentence with a chuckle, hoping the laughter would sooth her nerves and add confidence to her answer.

Josh Pratt, who if all went well today would sign on to be her campaign manager, twisted his mouth in a way that told Charlotte he wasn’t sure he believed her. He had a tiny blob of something yellow, maybe mustard, on the side of his thin lips. As he asked his questions, Charlotte had a hard time focusing on anything except for the golden dribble.

I’m running for national political office, she wanted to answer back. Ask me my thoughts on immigration, on the flat tax, on school vouchers, abortion rights. How much do I think we can raise the minimum wage? Can I bring more jobs to Pennsylvania? Will I create more affordable housing? Will I fight for college tuition assistance? What do I think about trade with the Chinese? Why does my marriage matter?

“You’re thinking, ‘Why does it matter?’ Why does your husband matter?” Josh read her mind. “Your husband matters. Your marriage matters. As a woman, you bear the burden of having to appear to be charismatic, smart, well-groomed, nice, but not too nice. If you’re married, you need to look happily married. If you have kids, you should be the mother of the year.”

“Goddammit. It’s 2017. There are plenty of women in Congress. A woman ran for president. It shouldn’t matter that I don’t have a penis.” Charlotte rolled her eyes. “It’s unbelievable that we have to deal with that kind of shit anymore.”

“Well, I’m sorry, but it matters a lot.” Josh shot her a stoic stare. “You do still have to deal with this shit. No one likes to say that out loud, but it’s true. You’re running in a state that’s never elected a woman to the Senate or as governor. That should tell you something.”

“Tug Slaughter is a serial philanderer,” Charlotte fired back at Josh. Pennsylvania’s longtime incumbent senator Ted “Tug” Slaughter had been married three times—his current wife was thirty-five years younger than he. The man was a walking cliché. For more than forty years, Slaughter had reigned as the senior senator from the state. Most men in Congress would be easy to miss in a crowd. Not Slaughter. Pushing eighty, the man still oozed raw ego. He was known to strip his shirt off and perform sit-ups onstage at events. Just last month he’d climbed the trestle of the Black Bridge in Marshfield Station with a pack of teenagers and leapt into the icy Delaware River below. Last winter he announced that he donated a kidney to a complete stranger he’d met at an Eagles game.

“It’s true, Tug does more cocktail waitresses than he does lawmaking, but he’s not the one who needs to create a legitimate candidacy. You do.” Josh had an answer for everything.

“That’s bullshit.”

Charlotte drummed her nails on her desktop, an expensive slab of glass through which she could see her boot tapping the wooden floor. She’d flown Josh here to Palo Alto from Philadelphia on her dime to convince him to run her campaign. He’d insisted on first class because he knew she could afford it, and Charlotte took this as a sign that he didn’t think he needed to impress her. All the right people told Charlotte that hiring Josh, a political wunderkind with four consecutive congressional wins under his belt, could give her a solid shot at winning. She needed him more than he needed her money, though she knew that if he said yes to working with her, she would be paying him in the high six figures for a little more than a year.

Josh paused and smiled. “You curse like a dockworker. You don’t look like someone with such a foul mouth, with your expensive linen suit, sitting in this glass-walled aquarium in the heart of Silicon Valley.”

She was suddenly conscious of what she looked like to him. At forty-seven, Charlotte was often complimented on the fact that she had aged well, and she’d heard it enough that she allowed it to be something she took pride in. She had what her mother once described as a plain face and a sturdy build, meaning she had broad shoulders and a flat chest that persisted into adulthood. She knew her hair was her best feature, more chestnut than brown, with strawberry highlights and just a few strands of silver she easily extracted at the roots. After half a lifetime of feeling insecure about her looks, in her thirties she’d learned to accentuate her best features and had come to see herself as pretty but not beautiful. She knew the distinction had made it easier for her to succeed in a male-dominated industry.

Meanwhile, Charlotte thought Josh looked ten years younger than his actual age, which Google informed her was thirty-five and, with his baby face, husky belly, and enthusiastic acne sprinkled across his cheeks, nothing like the kind of man who played the kind of three-dimensional chess required to get a person elected to national office. He wore dark jeans, a blue blazer, pristine Stan Smith Adidas with black laces, and a rumpled Phillies T-shirt. It took swagger to waltz into a business meeting in sneakers with mustard on his face and Charlotte knew it gave him the upper hand.

“Well, I curse more like a teamster,” Charlotte corrected Josh. “I spent too many nights at my dad’s union meetings.” Marty Walsh might have been a drunk, but he’d been a happy drunk, and because happy drunks are endearing to children, like Santa Claus and puppets, from an early age Charlotte had wanted to be around him all the time. On evenings when her mother couldn’t get out of bed, he brought her to his union meetings and sat her on the floor while deeply angry white men—the room was always all men—cursed and complained about how the world owed them better. Years later, at Marty’s funeral, the same men had the same conversations. Back then those men were still progressive Democrats. Mistrust for authority and misplaced expectations had been the central tropes of Charlotte’s upbringing. When she closed her eyes, Charlotte could smell the Swisher Sweets and cheap beer and hear her father say: “These men work hard, Charlie. They deserve a good turn. Anyone who works an honest day deserves a good turn.” He’d had plenty of flaws, but above all Marty had been a hard worker, and it was that quality Charlotte chose to remember above the others.

“That will play well in rural PA—the cursing, the garbageman dad,” Josh said now. “Easy on the union talk though. Only 10.7 percent of Americans identify with a union these days. Play up the white-trash angle. When you run for office, your life history gets reduced to character points: ‘Daughter of trashman turns Silicon Valley executive and comes home to help voters get jobs like hers.’ That’s your brand now. It’s a better brand than ‘California millionaire who grows heirloom tomatoes, contributes to the Silver Circle of public radio, does yoga, and tries to save the spotted owl.’?”

“It’s actually the Chinook salmon we’re more concerned about these days,” Charlotte whipped back.

There were other stories Charlotte could have told Josh. Sometimes Charlotte’s mother, Annemarie, had picked up cleaning shifts at a retirement home in Scranton, scraping vomit off the bathroom walls while wearing thick yellow latex gloves. Unable to afford childcare, she’d brought Charlotte with her, placing the little girl on a stool with a book in the corner of the bathroom. But Annemarie had lost that job when they’d found out she was stealing pills from the patients. Meanwhile, Marty had been among the first laid off when Elk Hollow merged municipal services with Abington. He’d picked up some hours at the gas station before it went self-service. In his later years he’d worked as a janitor in the food services department of the University of Scranton. Some months they’d gotten food stamps that her dad was too proud to ever use at the Rainbow market, even when the electricity got shut off for five days. These were memories Charlotte had packed away into dusty boxes in her brain, and when she’d unpacked them, she’d been startled to realize she’d become the kind of woman who bought fifteen dollars worth of organic kale and thirty dollars of non-GMO chia seeds at the Menlo Park True Food Co-op. The trajectory from there to here was vertigo-inducing.

Charlotte’s eyes wandered to the couch on the other side of the room, where Leila Kelly, her executive assistant, raised her bushy eyebrows in tandem as if to ask, Do we really need this guy?

Josh glanced at his notes and continued. “You and Max Tanner have been married for twelve years, with three daughters under the age of six. You’re the COO of Humanity and he’s the head of engineering and product for the same company. How will that work exactly when you run? What will your husband be doing when you move your family to Pennsylvania?”

“Max is taking a sabbatical from the company and taking care of our girls.”

“Don’t say the word sabbatical. You sound elitist, like the kind of person who says ‘holiday’ instead of ‘vacation.’?”

Sitting in her corner office as the chief operating officer of the technology company that was single-handedly changing how the world did business, Charlotte felt assured in her use of any damn word she pleased. “We call it a sabbatical here at Humanity. We both chose to take one when I decided to run—when we decided I should run. We made a joint decision that Max would help raise our daughters so I could focus on the campaign.”

Charlotte cringed, remembering the intense marital negotiations it had taken to convince Max that her running for office and him becoming the primary caregiver for their small children would be good for them as a family. Even though she understood what he was giving up for her, she also felt vindicated that she deserved this and more from him after what he’d put her through.

“We can talk about how to spin your husband’s so-called sabbatical later,” Josh countered, wagging his head and making exaggerated air quotes with his hands around the word sabbatical. “Maybe Max works on a top secret project from home. Something with virtual reality. People love the idea of virtual reality. They have no idea what the hell it is, but they think it will change their shitty lives. Always say ‘Silicon Valley,’ never ‘San Francisco,’ by the way. San Francisco conjures up images of tie-dyed, pot-smoking, free-loving hippies and transgendered people who want to use your bathroom. ‘Silicon Valley big shot’ is more aspirational than ‘reality television star’ these days, and you and Max hopefully come with less baggage.”

Josh dredged up his next unpleasant topic. “Speaking of baggage, Max has a reputation for being a flirt. There are a few women who claim he made inappropriate remarks to them in the office.”

Adrenaline tiptoed up her spine, but outwardly Charlotte maintained total calm, a skill honed in years of boardrooms filled with other puffed-up men with expensive haircuts.

She took a sip of her lukewarm coffee, allowing her front teeth to clink against her mug. Her husband had been a flirt. It was a reflex for him, the way he made both men and women like him. He made inappropriate, vaguely vulgar jokes at the wrong times. He was a toucher. There was a time, not too long ago, when he would stroll into a team meeting and give both men and women uninvited shoulder massages during pep talks. He used to joke, “An unwanted shoulder massage is an oxymoron.” She’d made him stop telling that joke.

“All men flirt.” Charlotte held her breath and glanced again at Leila. When she made an excuse for her husband, she faltered and raised her voice an octave without intending to. “Do you have any evidence he did anything wrong? No Humanity employees will ever speak badly about Max or me. Everyone signed ironclad confidentiality agreements.”

“How do you know they’re ironclad enough?”

“I wrote them. I’m the COO.” She crossed and uncrossed her legs.

Josh’s chapped lips stretched into a smirk. “People talked to me, and if they talked to me they’ll talk to your opponent and to the press. But you make another excellent point. You have a bigger job than Max. He’s the VP of product and engineering. You’re one step away from the CEO. You run this company.” He waved his hand in an arc sweeping the room, indicating what lay beyond it—the 500,000-square-foot office complex designed by Zaha Hadid, her final project before she passed away. Outside Charlotte’s window she could see the ten-acre rooftop park with its man-made waterfalls and brutalist concrete climbing wall.

Josh continued. “I’ll bet that was tough on Max, having his wife as a boss, the big dog at one of the most powerful companies in the world.”

“My husband is a very evolved man, not a dinosaur.”

Josh rolled his eyes. “That would be a cute sound bite if we were living in Sweden. Don’t say that out loud on the campaign trail.”

He left Max behind for the moment. “Your girls. The twins, they’re five now and you conceived them through IVF?” Josh clearly enjoyed toying with people, had the look of a child dangling a pork chop in front of a starving dog as he asked his questions.

Charlotte allowed her eyes to narrow and her annoyance to rise to the surface. “Yes.”

“Designer babies.”

Don’t talk about my kids like that. I will strangle you with my bare hands. “Oh, Christ! Like hundreds of thousands of women, I had trouble getting pregnant and used modern medicine to help start our family.” Getting pregnant had been the hardest thing she’d ever done. It had convinced her over and over that she was a failure and had nearly broken her. She despised talking about it.

“Because you were old when you got pregnant? Forty-one?”

“Yes, among other things.” Charlotte glared at him. “I’d like to think you know better than to refer to a woman as old.”

Unfazed, Josh continued. “What other things?”

“My uterus sits at an inopportune angle for sperm to properly reach my eggs without assistance. I have sonograms of it, actually. Do you think we should release them on Instagram in advance of announcing the campaign? Maybe they could be our Christmas cards.”

Josh ignored her sarcasm. “IVF is an expensive procedure.”

“The company paid for it.” It was one of the things Charlotte was proudest of—not the fact that the company had paid for her own procedures, but that they paid for all fertility procedures for all Humanity employees. In an effort to keep more women at Humanity, she had instituted a policy of paid family planning for all employees. The plan included compensation for IVF, egg freezing, egg donation, and adoption. At the time, she’d had no idea she would need to take advantage of the benefit herself. With Humanity’s female retention at an all-time low, she’d seen a problem and fixed it. Solving problems and knowing how to fix things was the defining characteristic of Charlotte’s adulthood and had earned her a nickname in certain tech circles—the Fixer. It didn’t matter that she wasn’t the most creative thinker or most analytical person in a room: When she was presented with a problem, Charlotte Walsh could always fix it.

She’d done it quietly, but when the press had asked her about it in 2014—because funding family planning was still considered a rogue move in the twenty-first century—she’d explained, as if she were responding to a very small and not terribly bright child, that it was the right goddamned thing to do to keep talented women in the workforce. That quote had caught the eye of some powerful women’s groups: EMILY’s List, She Should Run, and the Pink Pussy Brigade, which had begun selling Pepto-pink T-shirts emblazoned with the words THE RIGHT THING TO DO on the front and CHARLOTTE WALSH FOR PRESIDENT on the back. After that, a publisher had asked her to write a book, a request which was flattering and daunting. She wrote every night after the girls went to sleep. Her editor offered her a ghost writer, but that felt too easy, and dishonest. She finished the thing in four months, beating their original deadline by sixty days because she secretly feared someone would realize they never should have asked her to write a book in the first place. Let’s Fix It stayed on the bestseller list for thirty-two weeks. When she’d become an unwitting hero for women in the workplace, the kind of people who talk about such things—political pundits, cable news journalists, political strategists, and under-stimulated men who live in their parents’ basements and spend twenty hours a day on Twitter—had started debating the merits of her running for office. Once someone suggests you’ll be good at doing something, it’s not long before your ego kicks in. From then on, Charlotte hadn’t been able to stop thinking about running.

“I’m not ashamed of getting IVF, or of how it was paid for, Josh.” Punctuating a sentence with someone’s name always made Charlotte feel like an unseasoned primary school teacher. “The policies I created for family planning at Humanity paved the way for a better future for women in corporate America.”

Josh rolled his eyes. “Save that for a tweet,” he said. “You should talk about it, but not too much. You can be a strong female candidate, but not a feminist candidate. There’s a difference. The subtle path is the surer one. It’s all in the nuance. And the hair.”

A gurgle of nausea swept through Charlotte’s belly as Josh reached out and twisted a lock of her hair around one of his stubby fingers.

“Thank God you didn’t chop off your hair when you had kids. At least seventy-three percent of male voters prefer women with long hair. Too many liberal lady politicians get that mom helmet. They look like a crop of nuns, or dykes, and men don’t like it even if they won’t admit it in an exit poll.”

This was part of his shtick, semantics as offensive as those of a cable talk show back when talk show hosts were still celebrated for being rude. Charlotte couldn’t believe she needed to hire someone she already couldn’t stand, but she didn’t have to like him; she liked what he could do for her.

Josh pivoted again. “Well, it’s nice that Humanity paid for your fancy treatments, but you could have afforded it with your fancy salary, no? Since you earned . . . let’s see. . . .” He paused while he looked down at his notes. “A salary of 1.7 million dollars last year. That doesn’t even include your stock options, which are more than fifty million. You know you could probably buy this race if you sold half those options?”

Josh carried on with something of a sneer even though, if he agreed to work with her, she would be paying him a salary that was pretty damn fancy. “Are you worried you’re too rich and fancy for the hardworking people of Pennsylvania?”

“Being rich worked for the guy sitting in the Oval Office, didn’t it?” she growled. “I was compensated for successfully running one of the fastest-growing companies in the world.”

Josh held his palm open in front of her face and snorted. “Don’t be angry. No one likes an angry woman.”

She wanted to bite his chubby hand. Instead, Charlotte batted his paw hard enough to hurt him.

“Goddammit, I am angry. That’s why I’m running.”

“Focus on the reasons why you’re angry so that people know you aren’t running just because you have the money to do it. But remember to speak softly and sweetly when you talk about those reasons.”

Perhaps sensing her disdain, Josh paused. The next time he looked at her his combative edge softened in a way that made him look almost friendly, like he was about to consider her as a human instead of a project.

“Look, I don’t like being the dick all the time, but you need someone like me to do this now. It isn’t going to be easy. You’re going to lose your privacy. The press will dredge up things you said and did twenty, even thirty years ago. You might not even remember them. Forget about personal liberty. You may need to do things you’re uncomfortable with, say things you don’t agree with, maybe even lie. Probably lie. Let’s be honest: You’re gonna lie a lot. Normal rules don’t apply any more. You’re running against a guy who spews fantasy like it’s gospel.”

Lying. If he only knew. Charlotte sucked a deep breath into her rib cage and wiped her hands on her black linen pants. Her palms were sticky with sweat. She didn’t fully comprehend yet what the campaign would ask of her, but she knew she was willing to do it. She was prepared to go all in, whatever it took. Just the potential of it exhilarated, terrified, and energized her in a way she hadn’t felt in years.

“We’re the good guys, Josh.” Charlotte realized how naïve she sounded only after the words left her mouth.

“Everyone thinks they’re the good guys. But we can’t all be good, can we?”

“I get it. I realize it’s not going to be easy.” She focused on Josh’s pumpkin-shaped head and called to mind the best advice Rosalind Waters, her old boss and mentor, had given her regarding difficult men. That had been more than twenty years ago and Charlotte had only just started working for the Maryland governor when a right-wing conservative radio host baited Rosalind by telling her that deep down some women really just wanted to be sexually harassed. “How do you handle it?” Charlotte asked afterward, disgusted, curious, and enraged on Rosalind’s behalf. “How do you listen to pigheaded crap like that and keep a straight face?”

Rosalind answered with her signature spiky wit. “I picture them with a ridiculous mustache. Any time a man talks down to you, or at you, or overexplains something to you, picture what they would look like with an excellent mustache. It could be a classic Tom Selleck, a Fu Manchu, a petite Hitler.” Rosalind, known to her friends as Roz, explained this with a sly smile. “If he already has a mustache, just give him a more creative one in your mind. It takes the sting out of whatever they’re saying and lets you concentrate on how to respond. Better than picturing them naked. No one wants to see those men naked, even their wives—especially their wives.” Charlotte also recalled Roz’s more recent advice, the advice she’d offered when she’d encouraged Charlotte to enter this race: “Only let the world see half of your ambition. Half of the world can’t handle seeing it all.”

Now Charlotte directed her gaze to Josh’s upper lip and gave him a Salvador Dalí, long and narrow, with the ends pointing toward the ceiling and just covering the smudge of mustard.

“This campaign isn’t about the fact that I’m a woman. It’s not about how I got pregnant and it’s not about my husband. It’s about the voters of Pennsylvania. It’s about disrupting a broken system.”

Josh delivered a pointed look and raised an eyebrow. “You’re good.”

“You have shit on your face.” Leila finally spoke, as she stood and walked halfway around the table to Josh and used her thumb to remove the yellow stain from his lip. Charlotte loved that about Leila, her willingness to inject herself into any conversation, to save Charlotte when she would never ask to be saved, to lick her finger and swipe it across a stranger’s mouth for her.

“None of this is going to hurt us,” Leila declared. “Charlie got IVF because she has a medical condition. Max was a shoulder rubber? A flirt? News flash . . . everyone likes to flirt with Max. You might find yourself flirting with Max. He’s going to be an asset on the campaign trail. He looks like Jon Hamm. He’s got the sexy day-old beard down pat. He wears flannel like a guy who works with his hands, has dimples for days, and can change a diaper in public in thirty seconds flat. Yes, women like him. But, more important, women voters will like him, a lot. You have nothing to worry about there.”

Leila strode confidently back to her seat in the corner of the room and returned to her note-taking.

“What are you?” Josh asked then, looking at Leila and tilting his head to the side, inspecting her face.

“What am I?” the young woman shot back with a smirk that indicated she knew exactly what he was asking.

Leila was asked this question on a weekly basis by colleagues, business associates, strangers on the street. The features inherited from her Sudanese mother and Irish father, a mismatched pair who parted ways shortly after their only daughter entered the world, caused confusion for anyone who wanted to place her in a particular box. Her parents’ intense but brief union had produced a child with cinnamon-colored skin, light brown freckles, bright green eyes as vigilant as an alley cat’s, and thick dark hair that she wore in a meaty braid on top of her head, coiled like a cobra. Charlotte had heard all of Leila’s responses to the “what are you?” question, ranging from the polite “I’m just an all-American mutt” to the cynical “I was created in a lab to breed the women of the future” to the defiant “What are you?”

It had been nine years since Charlotte hired Leila at Humanity just after Leila had finished her classes at San Jose State on a full scholarship. They had the scholarship-kid thing in common. Leila waltzed into that first interview wearing scuffed teal pumps from Goodwill and delivered an hour-long PowerPoint presentation about how she would make Charlotte’s life easier. She was likable because she didn’t need to be liked, she only wanted to be seen as capable. Charlotte appreciated her ambition and confidence and hired her as a personal assistant later that afternoon.

Leila leaned back onto the couch now. She tugged at her ruby-colored pencil skirt, the one with fat brass buttons up the front. She’d tucked a man’s oxford into the high waist and topped it with a black bolero jacket. Leila called seventies-era Anjelica Huston her personal style muse. She regularly chided Charlotte for her simpler, more conservative taste in clothing. She’d insist: “Charlie, we live in a world where male billionaires dress like they’re homeless. It’s our duty to bring the style to this valley.”

Leila gave Josh her honest answer. “I’m half Sudanese, half Irish, born and raised in Oakland. My mom came here when she was sixteen, applied for political asylum because being Christian in Khartoum could get you killed. My dad played the fiddle and had kind eyes. And even though she was a sweet Jesus-fearing girl, he introduced her to the glory of the Irish car bomb one night in a bar called McGlinchey’s and they made me. Happy?”

Josh bit his bottom lip. Leila clearly unnerved him. “You might want to reconsider the nose ring on the campaign trail. If you’re coming, that is?”

It was never in question that Leila would accompany Charlotte to Pennsylvania, even though Charlotte had warned her it would mean putting her personal life on hold for more than a year.

Leila fingered the black hoop through her septum and shrugged. “I’ll think about it.”

Josh turned his attention back to Charlotte. “Speaking of families . . . your brother? Some guys in Elk Hollow told me he’s . . . Hold on, let me get the wording right.” Josh threw a glance at his notes. “?‘A drunk just like his dad and a pill-popping freak.’ How accurate is that?”

Charlotte had no idea how accurate it was. Paul, older than her by two years, had a long history of abusing any substance he could get his hands on. His vices were tempered only by his long-suffering wife, Kara, and his inability to afford to maintain a serious addiction. But Charlotte hadn’t spoken to him in about five years. During their last conversation he’d asked her to loan him $100,000 to start a hydroponic marijuana business in his basement. When Charlotte refused, Paul stopped returning her texts.

“I’m not sure.”

“You need to figure it out. Spend time with him. Talk to the wife. Get a better sense of what we’re dealing with. You should have a strong family connection in the state since you’ve been gone for so long. You’re planning to move back to Elk Hollow? Yes?”

Elk Hollow, in the far northeastern corner of Pennsylvania, was just forty-five minutes from Scranton and three hours from Philadelphia when there was no traffic on the turnpike. “Yes. We’re moving into the house where I grew up.”

Charlotte glanced at her phone as it buzzed in her lap. This was the third time Max had called. “I need to call my husband.”

Josh raised an eyebrow and shook his head. “Your husband can wait. This is my time right now.”

People didn’t tell Charlotte Walsh what to do, or at least they hadn’t in a long time.

“Fine. I’ll send a text.” She looked at the phone again. Max had beaten her to the punch.

Charlie-bird?? How’s the boy wonder campaign manager? Pick up phone!

Josh craned his neck to see her screen. “Boy Wonder—I like that.” He nodded his approval, showing no qualms about his invasion of her privacy. “Nicer than what people usually call me. But Charlie, I’m going to need your full attention right now.” He smiled when he used her nickname, plucked the phone gently from her hand, placed it in his own back pocket, and picked up where he’d left off. To her surprise, Charlotte let him do it.

“Elk Hollow . . .” Josh let the name of the town dribble off his tongue. “It’s good. You’re smart. Any path to regaining power in Congress has to go through the small towns. Moving back to your hometown is what I would have advised you to do if you’d hired me three months ago, but you called me late. You’re behind already. How much money have you raised?”

Charlotte was ready to loan the campaign the initial chunk of funding, $500,000 out of her personal bank account to get up and running. Because a cadre of very rich people saw her as part of what they liked to refer to as the Resistance with a capital R, she’d been promised a handful of six-figure and even a couple of seven-figure checks.

“A couple million.”

Josh whistled through pursed lips. “You’ll need at least ten times that.” He leaned back in his chair and spread his legs wide. His next few sentences sounded to Charlotte more like an internal dialogue.

“I feel good about this. According to early focus-group data, voters like you. They appreciate the no-bullshit, take-charge attitude. They think you’re nice-looking. That matters more than you think, and even though they have no idea what you actually do at Humanity, they think it’s the kind of job an important person would have. Voters remember someone they think is important.” He paused and looked directly into her eyes. “But one last question. Be honest. Why you? Why now?”

“Does this mean you’re going to work for me?” She’d expected to feel relief, but instead felt a charge like a static shock—the feeling she’d just gotten away with something, the feeling that she might just be able to pull this off.

Josh held her phone in his hand now like he was considering whether to give it back to her. “I’ll call you tomorrow to give you my answer,” he said as he placed the device facedown on the table. “If we do this, I’ll always call. You will always pick up. I never text. Texting is for teenage girls and teachers trying to have sex with their students. If we work together, I’m the first person you talk to in the morning and the last person whose voice you hear before you go to bed. If you need to take a particularly difficult shit, I should probably know about it.”

Tomorrow was soon. Tomorrow was good. She flipped the phone over. There were five more messages from her husband, but she didn’t bother to open them.

“But answer my question,” Josh repeated himself. “Why you? Why now?”

Can’t it be as simple as “I think I can do a better job than the guy who has the job”? She imagined all the answers she could possibly give about why she wanted to run for office. There was the earnest one: the fact that politicians were failing Americans. Corporations were failing Americans. She hated the hate she saw every time she read the news. She felt terror and anger when she scrolled through Twitter. Americans were at each other’s throats and it was disgusting. She was scared to death of raising her daughters in this country. She wanted to help the kinds of people she’d grown up with have a better life. After the last election, she’d had a real road-to-Damascus moment where she’d stayed up nights wondering if she was doing enough of the right thing, if her corporate job was all bullshit.

All of that was true.

Then there was the honest answer: Her decision to run for office had been born of a combination of idealism, guilt, and ego. The more she had thought about it, mostly late at night when she couldn’t sleep and the voices in her head reminded her she was crazy for even thinking she had what it took to run for political office, the more clearly she’d begun to recognize her motivations. In the two decades she’d worked at Humanity, their innovations in productivity had put hundreds of thousands of Americans out of a job, and entering government could give her the tools to help fix what she’d broken.

And there was another answer, the one it had taken her years to be comfortable articulating. But it was the one she knew Josh would appreciate. This was the first time she allowed herself to say the words out loud, and she grinned with a small shrug of her shoulders when she said them. “I like to win.”

Partial transcript of keynote interview between Charlotte Walsh and news anchor Erika Cabot at the Women Are the Future conference in New York City on August 1, 2017. Segments of this talk were broadcast on MSNBC.

Erika Cabot: In the past five years you doubled the number of women in management positions at Humanity. Some of the men both in and outside of the company have claimed that you actually favor female employees over men, that your goal is to marginalize men. What’s your response to that?

Charlotte Walsh: It’s ridiculous. For the record, I love men. The majority of the men I know are really good men and I adore them. I’m happy to see any employee stand up for themselves in the face of what they perceive as discrimination, even though I’ve said over and over again that I don’t promote anyone based on their sex or the color of their skin. I hire and promote people based on merit and merit alone. If I’ve done anything, it’s make it easier for highly qualified and talented women to have children and then to stay in the workforce after they’ve had their kids. That’s what contributed to doubling the number of women in management at Humanity. Those women are there because they deserve to be.

Erika Cabot: In your book Let’s Fix It, you devoted an entire chapter to how the government could follow Humanity’s lead by implementing similar policies and incentives to help keep women in the workforce. You were attacked by Tom Broadbent and Jim Sanders, two congressmen from Wyoming and Florida, respectively, for those statements as being a bleeding-heart West Coast liberal and a hysterical woman. What was your reaction to that?

Charlotte Walsh: At a certain point you have to stop caring whether people like you. Their comments just made me think, and not for the first time, what hateful, smug men run our country.

Erika Cabot: That brings me to the elephant in the room. Will you be the one to change it? Are you planning to run for national office?

Charlotte Walsh: This is where I tell you I’m flattered and have no plans to seek political office, right?

Erika Cabot: That’s usually how this works.

Charlotte Walsh: I’m not good at keeping things a secret, so I don’t see any point in giving you the runaround. Yes. I’m seriously considering a Senate run in Pennsylvania.

Erika Cabot: That’s the most honest answer I think I’ve gotten from a future politician. You’ve already got the support of plenty of women’s groups. You’ve got quite the tribe behind you. Do you think the future is female? The future of politics?

Charlotte Walsh: I’m hoping the future of politics is competent and hopeful and ready to fix the problems facing Americans. I’m proud to be a woman and I’m proud to be a candidate.

CHAPTER 1

July 15, 2017

479 days to Election Day

Tell people one true thing before you tell them a lie. Then it will be easier for them to believe the lie.

It wasn’t the best advice Marty Walsh ever gave to his daughter Charlotte, but it had stuck with her for almost forty years. Marty had been a garbage collector by trade, though he insisted “sanitation specialist” had a smarter ring to it. He wasn’t a successful man by most people’s standards and he died drunk in his bed before his fiftieth birthday. Now his daughter was running for the United States Senate and Marty’s words held a new utility for her.

Charlotte hadn’t expected her campaign to begin with an interrogation—an aggressive one at that—but the questions just kept coming.

“Have you ever used any drugs besides pot?”

“No.”

“Paid any undocumented workers under the table?”

“Nope.”

“Ever killed anyone?”

“Not yet.”

“Ever get an abortion?”

“No.”

“Infidelity in your marriage? Affairs? Secret ex-husband?”

“I love my husband. We don’t have anything to hide.” One of those things is true. Charlotte punctuated her sentence with a chuckle, hoping the laughter would sooth her nerves and add confidence to her answer.

Josh Pratt, who if all went well today would sign on to be her campaign manager, twisted his mouth in a way that told Charlotte he wasn’t sure he believed her. He had a tiny blob of something yellow, maybe mustard, on the side of his thin lips. As he asked his questions, Charlotte had a hard time focusing on anything except for the golden dribble.

I’m running for national political office, she wanted to answer back. Ask me my thoughts on immigration, on the flat tax, on school vouchers, abortion rights. How much do I think we can raise the minimum wage? Can I bring more jobs to Pennsylvania? Will I create more affordable housing? Will I fight for college tuition assistance? What do I think about trade with the Chinese? Why does my marriage matter?

“You’re thinking, ‘Why does it matter?’ Why does your husband matter?” Josh read her mind. “Your husband matters. Your marriage matters. As a woman, you bear the burden of having to appear to be charismatic, smart, well-groomed, nice, but not too nice. If you’re married, you need to look happily married. If you have kids, you should be the mother of the year.”

“Goddammit. It’s 2017. There are plenty of women in Congress. A woman ran for president. It shouldn’t matter that I don’t have a penis.” Charlotte rolled her eyes. “It’s unbelievable that we have to deal with that kind of shit anymore.”

“Well, I’m sorry, but it matters a lot.” Josh shot her a stoic stare. “You do still have to deal with this shit. No one likes to say that out loud, but it’s true. You’re running in a state that’s never elected a woman to the Senate or as governor. That should tell you something.”

“Tug Slaughter is a serial philanderer,” Charlotte fired back at Josh. Pennsylvania’s longtime incumbent senator Ted “Tug” Slaughter had been married three times—his current wife was thirty-five years younger than he. The man was a walking cliché. For more than forty years, Slaughter had reigned as the senior senator from the state. Most men in Congress would be easy to miss in a crowd. Not Slaughter. Pushing eighty, the man still oozed raw ego. He was known to strip his shirt off and perform sit-ups onstage at events. Just last month he’d climbed the trestle of the Black Bridge in Marshfield Station with a pack of teenagers and leapt into the icy Delaware River below. Last winter he announced that he donated a kidney to a complete stranger he’d met at an Eagles game.

“It’s true, Tug does more cocktail waitresses than he does lawmaking, but he’s not the one who needs to create a legitimate candidacy. You do.” Josh had an answer for everything.

“That’s bullshit.”

Charlotte drummed her nails on her desktop, an expensive slab of glass through which she could see her boot tapping the wooden floor. She’d flown Josh here to Palo Alto from Philadelphia on her dime to convince him to run her campaign. He’d insisted on first class because he knew she could afford it, and Charlotte took this as a sign that he didn’t think he needed to impress her. All the right people told Charlotte that hiring Josh, a political wunderkind with four consecutive congressional wins under his belt, could give her a solid shot at winning. She needed him more than he needed her money, though she knew that if he said yes to working with her, she would be paying him in the high six figures for a little more than a year.

Josh paused and smiled. “You curse like a dockworker. You don’t look like someone with such a foul mouth, with your expensive linen suit, sitting in this glass-walled aquarium in the heart of Silicon Valley.”

She was suddenly conscious of what she looked like to him. At forty-seven, Charlotte was often complimented on the fact that she had aged well, and she’d heard it enough that she allowed it to be something she took pride in. She had what her mother once described as a plain face and a sturdy build, meaning she had broad shoulders and a flat chest that persisted into adulthood. She knew her hair was her best feature, more chestnut than brown, with strawberry highlights and just a few strands of silver she easily extracted at the roots. After half a lifetime of feeling insecure about her looks, in her thirties she’d learned to accentuate her best features and had come to see herself as pretty but not beautiful. She knew the distinction had made it easier for her to succeed in a male-dominated industry.

Meanwhile, Charlotte thought Josh looked ten years younger than his actual age, which Google informed her was thirty-five and, with his baby face, husky belly, and enthusiastic acne sprinkled across his cheeks, nothing like the kind of man who played the kind of three-dimensional chess required to get a person elected to national office. He wore dark jeans, a blue blazer, pristine Stan Smith Adidas with black laces, and a rumpled Phillies T-shirt. It took swagger to waltz into a business meeting in sneakers with mustard on his face and Charlotte knew it gave him the upper hand.

“Well, I curse more like a teamster,” Charlotte corrected Josh. “I spent too many nights at my dad’s union meetings.” Marty Walsh might have been a drunk, but he’d been a happy drunk, and because happy drunks are endearing to children, like Santa Claus and puppets, from an early age Charlotte had wanted to be around him all the time. On evenings when her mother couldn’t get out of bed, he brought her to his union meetings and sat her on the floor while deeply angry white men—the room was always all men—cursed and complained about how the world owed them better. Years later, at Marty’s funeral, the same men had the same conversations. Back then those men were still progressive Democrats. Mistrust for authority and misplaced expectations had been the central tropes of Charlotte’s upbringing. When she closed her eyes, Charlotte could smell the Swisher Sweets and cheap beer and hear her father say: “These men work hard, Charlie. They deserve a good turn. Anyone who works an honest day deserves a good turn.” He’d had plenty of flaws, but above all Marty had been a hard worker, and it was that quality Charlotte chose to remember above the others.

“That will play well in rural PA—the cursing, the garbageman dad,” Josh said now. “Easy on the union talk though. Only 10.7 percent of Americans identify with a union these days. Play up the white-trash angle. When you run for office, your life history gets reduced to character points: ‘Daughter of trashman turns Silicon Valley executive and comes home to help voters get jobs like hers.’ That’s your brand now. It’s a better brand than ‘California millionaire who grows heirloom tomatoes, contributes to the Silver Circle of public radio, does yoga, and tries to save the spotted owl.’?”

“It’s actually the Chinook salmon we’re more concerned about these days,” Charlotte whipped back.

There were other stories Charlotte could have told Josh. Sometimes Charlotte’s mother, Annemarie, had picked up cleaning shifts at a retirement home in Scranton, scraping vomit off the bathroom walls while wearing thick yellow latex gloves. Unable to afford childcare, she’d brought Charlotte with her, placing the little girl on a stool with a book in the corner of the bathroom. But Annemarie had lost that job when they’d found out she was stealing pills from the patients. Meanwhile, Marty had been among the first laid off when Elk Hollow merged municipal services with Abington. He’d picked up some hours at the gas station before it went self-service. In his later years he’d worked as a janitor in the food services department of the University of Scranton. Some months they’d gotten food stamps that her dad was too proud to ever use at the Rainbow market, even when the electricity got shut off for five days. These were memories Charlotte had packed away into dusty boxes in her brain, and when she’d unpacked them, she’d been startled to realize she’d become the kind of woman who bought fifteen dollars worth of organic kale and thirty dollars of non-GMO chia seeds at the Menlo Park True Food Co-op. The trajectory from there to here was vertigo-inducing.

Charlotte’s eyes wandered to the couch on the other side of the room, where Leila Kelly, her executive assistant, raised her bushy eyebrows in tandem as if to ask, Do we really need this guy?

Josh glanced at his notes and continued. “You and Max Tanner have been married for twelve years, with three daughters under the age of six. You’re the COO of Humanity and he’s the head of engineering and product for the same company. How will that work exactly when you run? What will your husband be doing when you move your family to Pennsylvania?”

“Max is taking a sabbatical from the company and taking care of our girls.”

“Don’t say the word sabbatical. You sound elitist, like the kind of person who says ‘holiday’ instead of ‘vacation.’?”

Sitting in her corner office as the chief operating officer of the technology company that was single-handedly changing how the world did business, Charlotte felt assured in her use of any damn word she pleased. “We call it a sabbatical here at Humanity. We both chose to take one when I decided to run—when we decided I should run. We made a joint decision that Max would help raise our daughters so I could focus on the campaign.”

Charlotte cringed, remembering the intense marital negotiations it had taken to convince Max that her running for office and him becoming the primary caregiver for their small children would be good for them as a family. Even though she understood what he was giving up for her, she also felt vindicated that she deserved this and more from him after what he’d put her through.

“We can talk about how to spin your husband’s so-called sabbatical later,” Josh countered, wagging his head and making exaggerated air quotes with his hands around the word sabbatical. “Maybe Max works on a top secret project from home. Something with virtual reality. People love the idea of virtual reality. They have no idea what the hell it is, but they think it will change their shitty lives. Always say ‘Silicon Valley,’ never ‘San Francisco,’ by the way. San Francisco conjures up images of tie-dyed, pot-smoking, free-loving hippies and transgendered people who want to use your bathroom. ‘Silicon Valley big shot’ is more aspirational than ‘reality television star’ these days, and you and Max hopefully come with less baggage.”

Josh dredged up his next unpleasant topic. “Speaking of baggage, Max has a reputation for being a flirt. There are a few women who claim he made inappropriate remarks to them in the office.”

Adrenaline tiptoed up her spine, but outwardly Charlotte maintained total calm, a skill honed in years of boardrooms filled with other puffed-up men with expensive haircuts.

She took a sip of her lukewarm coffee, allowing her front teeth to clink against her mug. Her husband had been a flirt. It was a reflex for him, the way he made both men and women like him. He made inappropriate, vaguely vulgar jokes at the wrong times. He was a toucher. There was a time, not too long ago, when he would stroll into a team meeting and give both men and women uninvited shoulder massages during pep talks. He used to joke, “An unwanted shoulder massage is an oxymoron.” She’d made him stop telling that joke.

“All men flirt.” Charlotte held her breath and glanced again at Leila. When she made an excuse for her husband, she faltered and raised her voice an octave without intending to. “Do you have any evidence he did anything wrong? No Humanity employees will ever speak badly about Max or me. Everyone signed ironclad confidentiality agreements.”

“How do you know they’re ironclad enough?”

“I wrote them. I’m the COO.” She crossed and uncrossed her legs.

Josh’s chapped lips stretched into a smirk. “People talked to me, and if they talked to me they’ll talk to your opponent and to the press. But you make another excellent point. You have a bigger job than Max. He’s the VP of product and engineering. You’re one step away from the CEO. You run this company.” He waved his hand in an arc sweeping the room, indicating what lay beyond it—the 500,000-square-foot office complex designed by Zaha Hadid, her final project before she passed away. Outside Charlotte’s window she could see the ten-acre rooftop park with its man-made waterfalls and brutalist concrete climbing wall.

Josh continued. “I’ll bet that was tough on Max, having his wife as a boss, the big dog at one of the most powerful companies in the world.”

“My husband is a very evolved man, not a dinosaur.”

Josh rolled his eyes. “That would be a cute sound bite if we were living in Sweden. Don’t say that out loud on the campaign trail.”

He left Max behind for the moment. “Your girls. The twins, they’re five now and you conceived them through IVF?” Josh clearly enjoyed toying with people, had the look of a child dangling a pork chop in front of a starving dog as he asked his questions.

Charlotte allowed her eyes to narrow and her annoyance to rise to the surface. “Yes.”

“Designer babies.”

Don’t talk about my kids like that. I will strangle you with my bare hands. “Oh, Christ! Like hundreds of thousands of women, I had trouble getting pregnant and used modern medicine to help start our family.” Getting pregnant had been the hardest thing she’d ever done. It had convinced her over and over that she was a failure and had nearly broken her. She despised talking about it.

“Because you were old when you got pregnant? Forty-one?”

“Yes, among other things.” Charlotte glared at him. “I’d like to think you know better than to refer to a woman as old.”

Unfazed, Josh continued. “What other things?”

“My uterus sits at an inopportune angle for sperm to properly reach my eggs without assistance. I have sonograms of it, actually. Do you think we should release them on Instagram in advance of announcing the campaign? Maybe they could be our Christmas cards.”

Josh ignored her sarcasm. “IVF is an expensive procedure.”

“The company paid for it.” It was one of the things Charlotte was proudest of—not the fact that the company had paid for her own procedures, but that they paid for all fertility procedures for all Humanity employees. In an effort to keep more women at Humanity, she had instituted a policy of paid family planning for all employees. The plan included compensation for IVF, egg freezing, egg donation, and adoption. At the time, she’d had no idea she would need to take advantage of the benefit herself. With Humanity’s female retention at an all-time low, she’d seen a problem and fixed it. Solving problems and knowing how to fix things was the defining characteristic of Charlotte’s adulthood and had earned her a nickname in certain tech circles—the Fixer. It didn’t matter that she wasn’t the most creative thinker or most analytical person in a room: When she was presented with a problem, Charlotte Walsh could always fix it.

She’d done it quietly, but when the press had asked her about it in 2014—because funding family planning was still considered a rogue move in the twenty-first century—she’d explained, as if she were responding to a very small and not terribly bright child, that it was the right goddamned thing to do to keep talented women in the workforce. That quote had caught the eye of some powerful women’s groups: EMILY’s List, She Should Run, and the Pink Pussy Brigade, which had begun selling Pepto-pink T-shirts emblazoned with the words THE RIGHT THING TO DO on the front and CHARLOTTE WALSH FOR PRESIDENT on the back. After that, a publisher had asked her to write a book, a request which was flattering and daunting. She wrote every night after the girls went to sleep. Her editor offered her a ghost writer, but that felt too easy, and dishonest. She finished the thing in four months, beating their original deadline by sixty days because she secretly feared someone would realize they never should have asked her to write a book in the first place. Let’s Fix It stayed on the bestseller list for thirty-two weeks. When she’d become an unwitting hero for women in the workplace, the kind of people who talk about such things—political pundits, cable news journalists, political strategists, and under-stimulated men who live in their parents’ basements and spend twenty hours a day on Twitter—had started debating the merits of her running for office. Once someone suggests you’ll be good at doing something, it’s not long before your ego kicks in. From then on, Charlotte hadn’t been able to stop thinking about running.

“I’m not ashamed of getting IVF, or of how it was paid for, Josh.” Punctuating a sentence with someone’s name always made Charlotte feel like an unseasoned primary school teacher. “The policies I created for family planning at Humanity paved the way for a better future for women in corporate America.”

Josh rolled his eyes. “Save that for a tweet,” he said. “You should talk about it, but not too much. You can be a strong female candidate, but not a feminist candidate. There’s a difference. The subtle path is the surer one. It’s all in the nuance. And the hair.”

A gurgle of nausea swept through Charlotte’s belly as Josh reached out and twisted a lock of her hair around one of his stubby fingers.

“Thank God you didn’t chop off your hair when you had kids. At least seventy-three percent of male voters prefer women with long hair. Too many liberal lady politicians get that mom helmet. They look like a crop of nuns, or dykes, and men don’t like it even if they won’t admit it in an exit poll.”

This was part of his shtick, semantics as offensive as those of a cable talk show back when talk show hosts were still celebrated for being rude. Charlotte couldn’t believe she needed to hire someone she already couldn’t stand, but she didn’t have to like him; she liked what he could do for her.

Josh pivoted again. “Well, it’s nice that Humanity paid for your fancy treatments, but you could have afforded it with your fancy salary, no? Since you earned . . . let’s see. . . .” He paused while he looked down at his notes. “A salary of 1.7 million dollars last year. That doesn’t even include your stock options, which are more than fifty million. You know you could probably buy this race if you sold half those options?”

Josh carried on with something of a sneer even though, if he agreed to work with her, she would be paying him a salary that was pretty damn fancy. “Are you worried you’re too rich and fancy for the hardworking people of Pennsylvania?”

“Being rich worked for the guy sitting in the Oval Office, didn’t it?” she growled. “I was compensated for successfully running one of the fastest-growing companies in the world.”

Josh held his palm open in front of her face and snorted. “Don’t be angry. No one likes an angry woman.”

She wanted to bite his chubby hand. Instead, Charlotte batted his paw hard enough to hurt him.

“Goddammit, I am angry. That’s why I’m running.”

“Focus on the reasons why you’re angry so that people know you aren’t running just because you have the money to do it. But remember to speak softly and sweetly when you talk about those reasons.”

Perhaps sensing her disdain, Josh paused. The next time he looked at her his combative edge softened in a way that made him look almost friendly, like he was about to consider her as a human instead of a project.

“Look, I don’t like being the dick all the time, but you need someone like me to do this now. It isn’t going to be easy. You’re going to lose your privacy. The press will dredge up things you said and did twenty, even thirty years ago. You might not even remember them. Forget about personal liberty. You may need to do things you’re uncomfortable with, say things you don’t agree with, maybe even lie. Probably lie. Let’s be honest: You’re gonna lie a lot. Normal rules don’t apply any more. You’re running against a guy who spews fantasy like it’s gospel.”

Lying. If he only knew. Charlotte sucked a deep breath into her rib cage and wiped her hands on her black linen pants. Her palms were sticky with sweat. She didn’t fully comprehend yet what the campaign would ask of her, but she knew she was willing to do it. She was prepared to go all in, whatever it took. Just the potential of it exhilarated, terrified, and energized her in a way she hadn’t felt in years.

“We’re the good guys, Josh.” Charlotte realized how naïve she sounded only after the words left her mouth.

“Everyone thinks they’re the good guys. But we can’t all be good, can we?”

“I get it. I realize it’s not going to be easy.” She focused on Josh’s pumpkin-shaped head and called to mind the best advice Rosalind Waters, her old boss and mentor, had given her regarding difficult men. That had been more than twenty years ago and Charlotte had only just started working for the Maryland governor when a right-wing conservative radio host baited Rosalind by telling her that deep down some women really just wanted to be sexually harassed. “How do you handle it?” Charlotte asked afterward, disgusted, curious, and enraged on Rosalind’s behalf. “How do you listen to pigheaded crap like that and keep a straight face?”

Rosalind answered with her signature spiky wit. “I picture them with a ridiculous mustache. Any time a man talks down to you, or at you, or overexplains something to you, picture what they would look like with an excellent mustache. It could be a classic Tom Selleck, a Fu Manchu, a petite Hitler.” Rosalind, known to her friends as Roz, explained this with a sly smile. “If he already has a mustache, just give him a more creative one in your mind. It takes the sting out of whatever they’re saying and lets you concentrate on how to respond. Better than picturing them naked. No one wants to see those men naked, even their wives—especially their wives.” Charlotte also recalled Roz’s more recent advice, the advice she’d offered when she’d encouraged Charlotte to enter this race: “Only let the world see half of your ambition. Half of the world can’t handle seeing it all.”

Now Charlotte directed her gaze to Josh’s upper lip and gave him a Salvador Dalí, long and narrow, with the ends pointing toward the ceiling and just covering the smudge of mustard.

“This campaign isn’t about the fact that I’m a woman. It’s not about how I got pregnant and it’s not about my husband. It’s about the voters of Pennsylvania. It’s about disrupting a broken system.”

Josh delivered a pointed look and raised an eyebrow. “You’re good.”

“You have shit on your face.” Leila finally spoke, as she stood and walked halfway around the table to Josh and used her thumb to remove the yellow stain from his lip. Charlotte loved that about Leila, her willingness to inject herself into any conversation, to save Charlotte when she would never ask to be saved, to lick her finger and swipe it across a stranger’s mouth for her.

“None of this is going to hurt us,” Leila declared. “Charlie got IVF because she has a medical condition. Max was a shoulder rubber? A flirt? News flash . . . everyone likes to flirt with Max. You might find yourself flirting with Max. He’s going to be an asset on the campaign trail. He looks like Jon Hamm. He’s got the sexy day-old beard down pat. He wears flannel like a guy who works with his hands, has dimples for days, and can change a diaper in public in thirty seconds flat. Yes, women like him. But, more important, women voters will like him, a lot. You have nothing to worry about there.”

Leila strode confidently back to her seat in the corner of the room and returned to her note-taking.

“What are you?” Josh asked then, looking at Leila and tilting his head to the side, inspecting her face.

“What am I?” the young woman shot back with a smirk that indicated she knew exactly what he was asking.

Leila was asked this question on a weekly basis by colleagues, business associates, strangers on the street. The features inherited from her Sudanese mother and Irish father, a mismatched pair who parted ways shortly after their only daughter entered the world, caused confusion for anyone who wanted to place her in a particular box. Her parents’ intense but brief union had produced a child with cinnamon-colored skin, light brown freckles, bright green eyes as vigilant as an alley cat’s, and thick dark hair that she wore in a meaty braid on top of her head, coiled like a cobra. Charlotte had heard all of Leila’s responses to the “what are you?” question, ranging from the polite “I’m just an all-American mutt” to the cynical “I was created in a lab to breed the women of the future” to the defiant “What are you?”

It had been nine years since Charlotte hired Leila at Humanity just after Leila had finished her classes at San Jose State on a full scholarship. They had the scholarship-kid thing in common. Leila waltzed into that first interview wearing scuffed teal pumps from Goodwill and delivered an hour-long PowerPoint presentation about how she would make Charlotte’s life easier. She was likable because she didn’t need to be liked, she only wanted to be seen as capable. Charlotte appreciated her ambition and confidence and hired her as a personal assistant later that afternoon.

Leila leaned back onto the couch now. She tugged at her ruby-colored pencil skirt, the one with fat brass buttons up the front. She’d tucked a man’s oxford into the high waist and topped it with a black bolero jacket. Leila called seventies-era Anjelica Huston her personal style muse. She regularly chided Charlotte for her simpler, more conservative taste in clothing. She’d insist: “Charlie, we live in a world where male billionaires dress like they’re homeless. It’s our duty to bring the style to this valley.”

Leila gave Josh her honest answer. “I’m half Sudanese, half Irish, born and raised in Oakland. My mom came here when she was sixteen, applied for political asylum because being Christian in Khartoum could get you killed. My dad played the fiddle and had kind eyes. And even though she was a sweet Jesus-fearing girl, he introduced her to the glory of the Irish car bomb one night in a bar called McGlinchey’s and they made me. Happy?”

Josh bit his bottom lip. Leila clearly unnerved him. “You might want to reconsider the nose ring on the campaign trail. If you’re coming, that is?”

It was never in question that Leila would accompany Charlotte to Pennsylvania, even though Charlotte had warned her it would mean putting her personal life on hold for more than a year.

Leila fingered the black hoop through her septum and shrugged. “I’ll think about it.”

Josh turned his attention back to Charlotte. “Speaking of families . . . your brother? Some guys in Elk Hollow told me he’s . . . Hold on, let me get the wording right.” Josh threw a glance at his notes. “?‘A drunk just like his dad and a pill-popping freak.’ How accurate is that?”

Charlotte had no idea how accurate it was. Paul, older than her by two years, had a long history of abusing any substance he could get his hands on. His vices were tempered only by his long-suffering wife, Kara, and his inability to afford to maintain a serious addiction. But Charlotte hadn’t spoken to him in about five years. During their last conversation he’d asked her to loan him $100,000 to start a hydroponic marijuana business in his basement. When Charlotte refused, Paul stopped returning her texts.

“I’m not sure.”

“You need to figure it out. Spend time with him. Talk to the wife. Get a better sense of what we’re dealing with. You should have a strong family connection in the state since you’ve been gone for so long. You’re planning to move back to Elk Hollow? Yes?”

Elk Hollow, in the far northeastern corner of Pennsylvania, was just forty-five minutes from Scranton and three hours from Philadelphia when there was no traffic on the turnpike. “Yes. We’re moving into the house where I grew up.”

Charlotte glanced at her phone as it buzzed in her lap. This was the third time Max had called. “I need to call my husband.”

Josh raised an eyebrow and shook his head. “Your husband can wait. This is my time right now.”

People didn’t tell Charlotte Walsh what to do, or at least they hadn’t in a long time.

“Fine. I’ll send a text.” She looked at the phone again. Max had beaten her to the punch.

Charlie-bird?? How’s the boy wonder campaign manager? Pick up phone!

Josh craned his neck to see her screen. “Boy Wonder—I like that.” He nodded his approval, showing no qualms about his invasion of her privacy. “Nicer than what people usually call me. But Charlie, I’m going to need your full attention right now.” He smiled when he used her nickname, plucked the phone gently from her hand, placed it in his own back pocket, and picked up where he’d left off. To her surprise, Charlotte let him do it.

“Elk Hollow . . .” Josh let the name of the town dribble off his tongue. “It’s good. You’re smart. Any path to regaining power in Congress has to go through the small towns. Moving back to your hometown is what I would have advised you to do if you’d hired me three months ago, but you called me late. You’re behind already. How much money have you raised?”

Charlotte was ready to loan the campaign the initial chunk of funding, $500,000 out of her personal bank account to get up and running. Because a cadre of very rich people saw her as part of what they liked to refer to as the Resistance with a capital R, she’d been promised a handful of six-figure and even a couple of seven-figure checks.

“A couple million.”

Josh whistled through pursed lips. “You’ll need at least ten times that.” He leaned back in his chair and spread his legs wide. His next few sentences sounded to Charlotte more like an internal dialogue.

“I feel good about this. According to early focus-group data, voters like you. They appreciate the no-bullshit, take-charge attitude. They think you’re nice-looking. That matters more than you think, and even though they have no idea what you actually do at Humanity, they think it’s the kind of job an important person would have. Voters remember someone they think is important.” He paused and looked directly into her eyes. “But one last question. Be honest. Why you? Why now?”

“Does this mean you’re going to work for me?” She’d expected to feel relief, but instead felt a charge like a static shock—the feeling she’d just gotten away with something, the feeling that she might just be able to pull this off.

Josh held her phone in his hand now like he was considering whether to give it back to her. “I’ll call you tomorrow to give you my answer,” he said as he placed the device facedown on the table. “If we do this, I’ll always call. You will always pick up. I never text. Texting is for teenage girls and teachers trying to have sex with their students. If we work together, I’m the first person you talk to in the morning and the last person whose voice you hear before you go to bed. If you need to take a particularly difficult shit, I should probably know about it.”

Tomorrow was soon. Tomorrow was good. She flipped the phone over. There were five more messages from her husband, but she didn’t bother to open them.

“But answer my question,” Josh repeated himself. “Why you? Why now?”

Can’t it be as simple as “I think I can do a better job than the guy who has the job”? She imagined all the answers she could possibly give about why she wanted to run for office. There was the earnest one: the fact that politicians were failing Americans. Corporations were failing Americans. She hated the hate she saw every time she read the news. She felt terror and anger when she scrolled through Twitter. Americans were at each other’s throats and it was disgusting. She was scared to death of raising her daughters in this country. She wanted to help the kinds of people she’d grown up with have a better life. After the last election, she’d had a real road-to-Damascus moment where she’d stayed up nights wondering if she was doing enough of the right thing, if her corporate job was all bullshit.

All of that was true.

Then there was the honest answer: Her decision to run for office had been born of a combination of idealism, guilt, and ego. The more she had thought about it, mostly late at night when she couldn’t sleep and the voices in her head reminded her she was crazy for even thinking she had what it took to run for political office, the more clearly she’d begun to recognize her motivations. In the two decades she’d worked at Humanity, their innovations in productivity had put hundreds of thousands of Americans out of a job, and entering government could give her the tools to help fix what she’d broken.

And there was another answer, the one it had taken her years to be comfortable articulating. But it was the one she knew Josh would appreciate. This was the first time she allowed herself to say the words out loud, and she grinned with a small shrug of her shoulders when she said them. “I like to win.”

Partial transcript of keynote interview between Charlotte Walsh and news anchor Erika Cabot at the Women Are the Future conference in New York City on August 1, 2017. Segments of this talk were broadcast on MSNBC.

Erika Cabot: In the past five years you doubled the number of women in management positions at Humanity. Some of the men both in and outside of the company have claimed that you actually favor female employees over men, that your goal is to marginalize men. What’s your response to that?

Charlotte Walsh: It’s ridiculous. For the record, I love men. The majority of the men I know are really good men and I adore them. I’m happy to see any employee stand up for themselves in the face of what they perceive as discrimination, even though I’ve said over and over again that I don’t promote anyone based on their sex or the color of their skin. I hire and promote people based on merit and merit alone. If I’ve done anything, it’s make it easier for highly qualified and talented women to have children and then to stay in the workforce after they’ve had their kids. That’s what contributed to doubling the number of women in management at Humanity. Those women are there because they deserve to be.

Erika Cabot: In your book Let’s Fix It, you devoted an entire chapter to how the government could follow Humanity’s lead by implementing similar policies and incentives to help keep women in the workforce. You were attacked by Tom Broadbent and Jim Sanders, two congressmen from Wyoming and Florida, respectively, for those statements as being a bleeding-heart West Coast liberal and a hysterical woman. What was your reaction to that?

Charlotte Walsh: At a certain point you have to stop caring whether people like you. Their comments just made me think, and not for the first time, what hateful, smug men run our country.

Erika Cabot: That brings me to the elephant in the room. Will you be the one to change it? Are you planning to run for national office?

Charlotte Walsh: This is where I tell you I’m flattered and have no plans to seek political office, right?

Erika Cabot: That’s usually how this works.

Charlotte Walsh: I’m not good at keeping things a secret, so I don’t see any point in giving you the runaround. Yes. I’m seriously considering a Senate run in Pennsylvania.

Erika Cabot: That’s the most honest answer I think I’ve gotten from a future politician. You’ve already got the support of plenty of women’s groups. You’ve got quite the tribe behind you. Do you think the future is female? The future of politics?

Charlotte Walsh: I’m hoping the future of politics is competent and hopeful and ready to fix the problems facing Americans. I’m proud to be a woman and I’m proud to be a candidate.

Descriere

From bestselling author Jo Piazza comes a novel about what happens when a woman wants it all: political power, marriage and happiness.