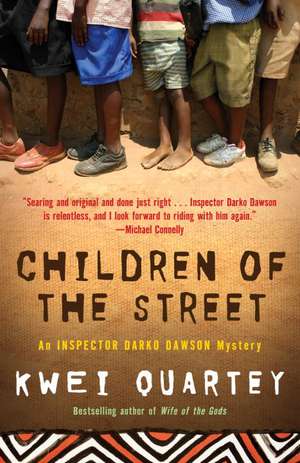

Children of the Street: An Inspector Darko Dawson Mystery: Inspector Darko Dawson Mysteries, cartea 02

Autor Kwei J. Quarteyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2011

Preț: 88.16 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.87€ • 17.61$ • 13.93£

16.87€ • 17.61$ • 13.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812981674

ISBN-10: 0812981677

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Random House Trade

Seria Inspector Darko Dawson Mysteries

ISBN-10: 0812981677

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Random House Trade

Seria Inspector Darko Dawson Mysteries

Extras

PART ONE

1

The call had come in on a Sunday morning in June.

"For this one," Detective Sergeant Chikata hadsaid, "I think they will need us."

On his Honda motorbike, Detective Inspector Darko Dawsonsped by industrial buildings along Ring Road West. The dead body was near theKorle Lagoon. He made it there in fifteen minutes. Even if Dawson's eyes hadbeen shut, the pervasive, foul smell of the lagoon would have announced to himthat he had arrived.

He turned onto Abossey Okai Road, which formed twobridges, the first of them over the refuse-choked Odaw River, which flowed intothe lagoon. Agbogbloshie Market on Dawson's left and Kokomba Market on hisright teemed with Sunday shoppers and hawkers trying to sell everything frombananas to sea crabs.

At the second bridge, over a much smaller channel oftarry, polluted water, there were umbrella-shaded market vendors, pedestrians,trucks, and cars mixed together in organized chaos. Dawson parked and lockedhis bike. Sprawling onto the riverbanks, a crowd of onlookers overflowed bothends of the bridge. Standing at over six feet, Dawson could see above mostpeople's heads. Detective Sergeant Chikata and a uniformed man Dawson didn'tknow were about a hundred meters up on the south bank of the channel. Framedapocalyptically against dense black smoke billowing from somewhere upstream,Deputy Superintendent Bright and three members of his crime scene team, all inmasks, gloves, and galoshes, were moving about knee-deep in the foul mire.

Dawson skirted the mass of the crowd and made his wayonto the bank. It was carpeted with litter, much of it plastic bottlesdiscarded without a second's thought after the contained water had been drunk.The rest of the junk included boxes, tin cans, abandoned clothing, trash bags,pieces of machinery, old tires, coconut husks, and unidentifiable bits of metaland plastic detritus. There was also the kind of human waste Dawson definitelydid not want his shoes to touch, some of it exposed, some of it in "flyingtoilets"-tossed black plastic bags with excrement inside.

The impossibly good-looking Detective Sergeant Chikata,Dawson's junior in rank in the Criminal Investigations Department (CID)Homicide Division, looked up as Dawson approached.

"Morning, Dawson."

"Morning, Chikata."

"Body of a dead male spotted in there thismorning."

"How did we get notified?"

Chikata introduced the bulky, flinty-eyed man next tohim. "This is Inspector Agyekum. He was the Korle Bu station officer thismorning."

Agyekum was Detective Inspector Dawson's rank equivalent,but as a general inspector he wore the standard, heavy, sweltering dark blueuniform of the Ghana Police Service (GPS) in contrast to CID's plainclothesmen.

"Morning, Inspector." Dawson shook hands,finishing with the customary mutual finger snap.

"I was starting my shift when a small boy came intothe station," Agyekum took up. "That's him there with ConstableGyamfi." He pointed his chin farther along the bank where a policeconstable stood over a boy of about eight sitting on the ground with his headdown and his arms folded tightly across his skinny body.

"Many people saw the body," Agyekum continued,"but because they fear the police, they just kept quiet. But the boy tookit upon himself to run over to the Korle Bu station to report it."

"He's a brave young man," Dawson said, lookingover at the boy with approval. "And then?"

"Constable Gyamfi took the report in the station andbrought it to me," Agyekum said, "then the two of us returned withthe boy. When I saw the body there, I decided to call the Crime SceneUnit."

"Very good," Dawson said. "Thankyou."

Dawson knew Police Constable Gyamfi from a previous casea year ago. He waved at the constable, who smiled and half waved, half salutedin return.

"Mr. Bright says he's quite sure it's ahomicide," Chikata said.

"Then it probably is," Dawson said.

Deputy Superintendent Bright, a trained serologist, washead of the CSU team. His hunches were seldom wrong.

Dawson moved a little closer to the water, which was thecolor of tar and almost the same consistency. He winced at its relentlessstench, but people living within smelling distance were used to it, or maybejust ignored it.

Bright and his two crime scene guys squelched around ?looking for an unlikely clue. There was so much garbage it would be a miracleif they found anything useful. Only Bright's relentless thoroughness andcommitment to excellence had deemed the search necessary. Others might havesimply reeled the corpse in without bothering.

The garbage partially camouflaged the dead body, whichwas facedown. On casual glance, it could have been mistaken for a big clump ofrubbish, and undoubtedly had been.

With glop sucking at his galoshes, Deputy SuperintendentBright joined Dawson and the other two men.

"Morning, Dawson." His voice sounded like thebass notes of a bassoon. "Please excuse my appearance and odor."

"Good morning, sir. I admire you for going inthere."

Bright looked down at his soiled outfit with a grimace."These are the last of our hazardous materials garb, so fortunately ornot, I won't be doing this again for a while."

"Any findings, sir?" Dawson asked.

"Besides the body? Nothing. Still suspect foul play,however. I know a dumped corpse when I see one. And this one is in terribleshape."

"When are you bringing it in?"

"We're almost ready for that now."

"Can you wait a few minutes? I don't want the boy tosee that."

"No problem, Dawson."

"Thank you, sir. It's good to have you around."Dawson turned and trotted up the bank.

2

The boy was still with Police Constable Gyamfi, who wasin his mid-twenties but looked so young he could have gone undercover as a highschool student. As Dawson approached, Gyamfi's face lit up with a smile ofstrong, white teeth-the kind that could snap the top off a beer bottle.

"Morning, Gyamfi," Dawson said as they claspedhands. "How are you? It's nice to see you again."

"Yes, sir, and you too."

"How're the wife and new daughter?"

"Very well, sir, thank you, sir."

"Good, I'm glad."

Gyamfi was a recent import from the rural town of Ketanuin the Volta Region. With Dawson's help and persistence, he had beentransferred to the police force in Accra, not an easy achievement in the GPS.He was a good man with great integrity and promise.

Dawson looked down at the boy, who didn't return thelook. He wore torn cutoff jeans, a soiled black-and-white muscle shirt that wastoo big for him, and slippers that were falling apart on his dusty feet. He wasstaring at a point on the ground in front of him. Dawson knelt down.

"How are you? I'm Darko. What's your name?"

The boy's eyes flitted up and away. "Sly."

Dawson held out his hand. Sly shook it after a second'sconsideration.

"Thank you for what you did," Dawson said."You were brave to go to the police station. Do you know that?"

Sly nodded tautly. Dawson lifted his face with a touch tohis chin.

"Are you all right?"

"Yes."

"I'm not going to do anything to you. I only want tobe your friend."

Sly nodded again. Dawson stood and reached for the boy'shand, pulling him up. "Let's go for a walk."

"Okay."

"While we're gone," Dawson said to Gyamfi,"I want you to talk to these people in the crowd. We need to know ifanyone saw anything this morning or last night in connection with the body. Weneed names, and we need a way to get back in touch with them. That might behard around here, but do your best."

"Yes, sir."

"And always remember faces, Gyamfi. Try to make yourmind a camera. You never know who you might run into later on."

Dawson turned away with Sly and steered him around thepack of spectators. As he and the boy walked past, every head turned to watchthem. Dawson took a quick but good look at all the faces, practicing what hehad just preached to his constable. In reality, the chance was remote that theywould get usable information from anyone. Watching policemen at work was okay,talking to them was not.

Dawson and Sly were now walking along the curve of theOdaw River's east bank toward the shacks of the slum in the distance.

"How old are you, Sly?"

"Nine."

"From northern Ghana?"

"Upper West Region."

Dawson had made an educated guess. Most of Agbogbloshie'sresidents came from northern Ghana.

"Where do you live?"

"Here in Sodom and Gomorrah."

It was the bitter, ironic nickname for Agbogbloshie,Accra's most notorious slum. Drugs, prostitution, rape, forty thousandsquatters, and practically every year a new but unsuccessful government plan torelocate them.

Dawson and Sly walked the beaten path through mounds oftrash containing the ubiquitous plastic bags and bottles, carcasses of old TVs,trashed scanners, mobile phones, air conditioners, refrigerators, fax machines,microwaves, dead computer monitors and defunct CPUs. To their left was amountain of electronic waste piled higher than Dawson's head.

"What were you doing this morning when you saw thatdead man in the water?" he asked Sly.

"Burning cables."

That was what caused the dense black smoke all along thebanks of the Odaw. The boys burned TV and computer cables to get at the copperwires, which they sold locally for fifty pesewas per kilo, or about eighteencents per pound.

Ahead was a line of teenage boys that made Dawson thinkof an assembly line, only this was disassembly. The first boy was breaking openthe back of an old TV monitor using a rock. The second was degreasing somecables with a solvent. Farther along still, a cable-burning session wasbeginning. Five boys of ages ten to fifteen were crowded around a mass ofprepped cables. All from northern Ghana, they addressed Sly in rapid-fireHausa. Although Dawson wasn't fluent in the language, it was obvious they wereasking who he was. Sly's response seemed to satisfy them because they noddedand smiled.

"I tell them you're my friend," Sly explained.

"Where did you learn English?" Dawson asked.

"I was schooling at my hometown before my fathertold me to come to Accra with my uncle."

"Are you continuing school here?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"My uncle says he won't send me to school. He justwants me to sell copper and make money."

Dawson said nothing to that, for now anyway.

The Hausa boys used insulation foam as kindling and acigarette lighter to start the burn. Poking the cables with sticks brought theneeded rush of oxygen and created a miniature inferno with a blast of deadlyblack smoke. Even though he was upwind from it, Dawson caught a good whiff andbacked away slightly, thinking of the toxicity of the fumes. With his foot, heflipped over a piece of plastic from a computer monitor and found a label thatread school district of philadelphia. Junked, unusable equipment that the richcountries passed off as charitable donations ended up right here inAgbogbloshie.

"Ask them if any of them saw the dead person backthere or heard anything about it," Dawson said to Sly.

The boy obliged. His friends, intent on their task,replied briefly.

"They didn't see anything," Sly said."They haven't heard anything."

Dawson nodded. He hadn't expected much more than that.Fact was, if the dead person wasn't a friend of theirs or otherwise important,it just wasn't of that much interest to them. Someone died. So what?

"Let's go," Dawson said to Sly. A littlefarther along he put his hand on the boy's head like he was palming a soccerball. "Burning that stuff is dangerous. There's poison in the smoke andyou're breathing it inside your body. You understand?"

Sly nodded, but uncertainly. Dawson wasn't sure he reallydid get it. He ruffled his companion's short, wiry hair. "You're a goodboy, Sly. Is your uncle at home?"

Sly was hesitant about something.

"You don't like your uncle?" Darko asked.

"Yes, I like him," Sly said.

But the changed tone of his voice, broken up like ableat, told Dawson he wasn't telling the truth.

"Don't be afraid," Dawson said. "I onlywant to talk to him."

Roaming the open land bordered by the Ring Road on thewest and the edge of the Odaw River on the east were a few grazing horses and aherd of placid, foraging cows, brought all the way from the northernterritories by migrants who had lived as nomads. It was a bizarre mixing ofrural lifestyle with the urban slum. Only in Accra, Dawson thought. Only inAccra.

Deep within Agbogbloshie, Sly walked with easy assurance,as if floating over the rocky ground. He skipped nonchalantly across guttersfilled to overflowing with garbage encased in opaque, grayish black glop. Heducked under laundry hung out to dry on clotheslines crisscrossing like railwaytracks. He took narrow, abruptly swerving passages between rows of ricketyhomes constructed of wood that just begged for a conflagration.

Life went on here with the same inevitability it doesanywhere else. People worked and traded, children played, women got their nailsdone, men had their hair cut, and a group of shirtless teenage boys watchedsoccer on a communal TV.

Here and there, Dawson caught a whiff of marijuana, or"wee," as it was popularly known. From his nasal passages, it wentlike a blast to a pleasure spot inside his brain. He felt that tug of desirethat told him he had not yet conquered his vice. Five months completely clean.One day at a time.

People asked Sly who his companion was. He gave the sameanswer every time. "He's Darko, my friend." It was best that way.They didn't take to policemen. If casual queries about the corpse in the lagoonyielded little to no useful information, it was still more than Dawson wouldget if people knew he was a detective.

They passed a small mosque that stood out as one of thefew brick buildings in Agbogbloshie. A man inside was prostrate on his prayermat.

"There is my house," Sly said, slowing down andpointing. "Where those boys are playing."

Four teenagers were kicking and heading a soccer ballback and forth to one another without allowing it to touch the ground. A mansat in front of a windowless, eight-foot-square wooden shack raised off theground on short stilts.

"Is that your uncle?" Dawson asked.

"Yes."

Sly's uncle saw them approaching. For a moment he didn'tmove, but he finally rose to his feet as they came closer. He was frowning-thepuzzled kind of frown-and then he looked wary.

"Good morning?" He was average height withsquinting eyes. His hair was graying at the temples and retreating from hisdome forehead. He had tribal marks on both cheeks.

"Good morning, sir. My name is Darko Dawson."

"Yessah. I'm Gamel." His voice was like gravel.

Behind him, the door of his living quarters was ajar, andDawson caught a glimpse of a thin foam floor mattress as holey as Swiss cheese.

1

The call had come in on a Sunday morning in June.

"For this one," Detective Sergeant Chikata hadsaid, "I think they will need us."

On his Honda motorbike, Detective Inspector Darko Dawsonsped by industrial buildings along Ring Road West. The dead body was near theKorle Lagoon. He made it there in fifteen minutes. Even if Dawson's eyes hadbeen shut, the pervasive, foul smell of the lagoon would have announced to himthat he had arrived.

He turned onto Abossey Okai Road, which formed twobridges, the first of them over the refuse-choked Odaw River, which flowed intothe lagoon. Agbogbloshie Market on Dawson's left and Kokomba Market on hisright teemed with Sunday shoppers and hawkers trying to sell everything frombananas to sea crabs.

At the second bridge, over a much smaller channel oftarry, polluted water, there were umbrella-shaded market vendors, pedestrians,trucks, and cars mixed together in organized chaos. Dawson parked and lockedhis bike. Sprawling onto the riverbanks, a crowd of onlookers overflowed bothends of the bridge. Standing at over six feet, Dawson could see above mostpeople's heads. Detective Sergeant Chikata and a uniformed man Dawson didn'tknow were about a hundred meters up on the south bank of the channel. Framedapocalyptically against dense black smoke billowing from somewhere upstream,Deputy Superintendent Bright and three members of his crime scene team, all inmasks, gloves, and galoshes, were moving about knee-deep in the foul mire.

Dawson skirted the mass of the crowd and made his wayonto the bank. It was carpeted with litter, much of it plastic bottlesdiscarded without a second's thought after the contained water had been drunk.The rest of the junk included boxes, tin cans, abandoned clothing, trash bags,pieces of machinery, old tires, coconut husks, and unidentifiable bits of metaland plastic detritus. There was also the kind of human waste Dawson definitelydid not want his shoes to touch, some of it exposed, some of it in "flyingtoilets"-tossed black plastic bags with excrement inside.

The impossibly good-looking Detective Sergeant Chikata,Dawson's junior in rank in the Criminal Investigations Department (CID)Homicide Division, looked up as Dawson approached.

"Morning, Dawson."

"Morning, Chikata."

"Body of a dead male spotted in there thismorning."

"How did we get notified?"

Chikata introduced the bulky, flinty-eyed man next tohim. "This is Inspector Agyekum. He was the Korle Bu station officer thismorning."

Agyekum was Detective Inspector Dawson's rank equivalent,but as a general inspector he wore the standard, heavy, sweltering dark blueuniform of the Ghana Police Service (GPS) in contrast to CID's plainclothesmen.

"Morning, Inspector." Dawson shook hands,finishing with the customary mutual finger snap.

"I was starting my shift when a small boy came intothe station," Agyekum took up. "That's him there with ConstableGyamfi." He pointed his chin farther along the bank where a policeconstable stood over a boy of about eight sitting on the ground with his headdown and his arms folded tightly across his skinny body.

"Many people saw the body," Agyekum continued,"but because they fear the police, they just kept quiet. But the boy tookit upon himself to run over to the Korle Bu station to report it."

"He's a brave young man," Dawson said, lookingover at the boy with approval. "And then?"

"Constable Gyamfi took the report in the station andbrought it to me," Agyekum said, "then the two of us returned withthe boy. When I saw the body there, I decided to call the Crime SceneUnit."

"Very good," Dawson said. "Thankyou."

Dawson knew Police Constable Gyamfi from a previous casea year ago. He waved at the constable, who smiled and half waved, half salutedin return.

"Mr. Bright says he's quite sure it's ahomicide," Chikata said.

"Then it probably is," Dawson said.

Deputy Superintendent Bright, a trained serologist, washead of the CSU team. His hunches were seldom wrong.

Dawson moved a little closer to the water, which was thecolor of tar and almost the same consistency. He winced at its relentlessstench, but people living within smelling distance were used to it, or maybejust ignored it.

Bright and his two crime scene guys squelched around ?looking for an unlikely clue. There was so much garbage it would be a miracleif they found anything useful. Only Bright's relentless thoroughness andcommitment to excellence had deemed the search necessary. Others might havesimply reeled the corpse in without bothering.

The garbage partially camouflaged the dead body, whichwas facedown. On casual glance, it could have been mistaken for a big clump ofrubbish, and undoubtedly had been.

With glop sucking at his galoshes, Deputy SuperintendentBright joined Dawson and the other two men.

"Morning, Dawson." His voice sounded like thebass notes of a bassoon. "Please excuse my appearance and odor."

"Good morning, sir. I admire you for going inthere."

Bright looked down at his soiled outfit with a grimace."These are the last of our hazardous materials garb, so fortunately ornot, I won't be doing this again for a while."

"Any findings, sir?" Dawson asked.

"Besides the body? Nothing. Still suspect foul play,however. I know a dumped corpse when I see one. And this one is in terribleshape."

"When are you bringing it in?"

"We're almost ready for that now."

"Can you wait a few minutes? I don't want the boy tosee that."

"No problem, Dawson."

"Thank you, sir. It's good to have you around."Dawson turned and trotted up the bank.

2

The boy was still with Police Constable Gyamfi, who wasin his mid-twenties but looked so young he could have gone undercover as a highschool student. As Dawson approached, Gyamfi's face lit up with a smile ofstrong, white teeth-the kind that could snap the top off a beer bottle.

"Morning, Gyamfi," Dawson said as they claspedhands. "How are you? It's nice to see you again."

"Yes, sir, and you too."

"How're the wife and new daughter?"

"Very well, sir, thank you, sir."

"Good, I'm glad."

Gyamfi was a recent import from the rural town of Ketanuin the Volta Region. With Dawson's help and persistence, he had beentransferred to the police force in Accra, not an easy achievement in the GPS.He was a good man with great integrity and promise.

Dawson looked down at the boy, who didn't return thelook. He wore torn cutoff jeans, a soiled black-and-white muscle shirt that wastoo big for him, and slippers that were falling apart on his dusty feet. He wasstaring at a point on the ground in front of him. Dawson knelt down.

"How are you? I'm Darko. What's your name?"

The boy's eyes flitted up and away. "Sly."

Dawson held out his hand. Sly shook it after a second'sconsideration.

"Thank you for what you did," Dawson said."You were brave to go to the police station. Do you know that?"

Sly nodded tautly. Dawson lifted his face with a touch tohis chin.

"Are you all right?"

"Yes."

"I'm not going to do anything to you. I only want tobe your friend."

Sly nodded again. Dawson stood and reached for the boy'shand, pulling him up. "Let's go for a walk."

"Okay."

"While we're gone," Dawson said to Gyamfi,"I want you to talk to these people in the crowd. We need to know ifanyone saw anything this morning or last night in connection with the body. Weneed names, and we need a way to get back in touch with them. That might behard around here, but do your best."

"Yes, sir."

"And always remember faces, Gyamfi. Try to make yourmind a camera. You never know who you might run into later on."

Dawson turned away with Sly and steered him around thepack of spectators. As he and the boy walked past, every head turned to watchthem. Dawson took a quick but good look at all the faces, practicing what hehad just preached to his constable. In reality, the chance was remote that theywould get usable information from anyone. Watching policemen at work was okay,talking to them was not.

Dawson and Sly were now walking along the curve of theOdaw River's east bank toward the shacks of the slum in the distance.

"How old are you, Sly?"

"Nine."

"From northern Ghana?"

"Upper West Region."

Dawson had made an educated guess. Most of Agbogbloshie'sresidents came from northern Ghana.

"Where do you live?"

"Here in Sodom and Gomorrah."

It was the bitter, ironic nickname for Agbogbloshie,Accra's most notorious slum. Drugs, prostitution, rape, forty thousandsquatters, and practically every year a new but unsuccessful government plan torelocate them.

Dawson and Sly walked the beaten path through mounds oftrash containing the ubiquitous plastic bags and bottles, carcasses of old TVs,trashed scanners, mobile phones, air conditioners, refrigerators, fax machines,microwaves, dead computer monitors and defunct CPUs. To their left was amountain of electronic waste piled higher than Dawson's head.

"What were you doing this morning when you saw thatdead man in the water?" he asked Sly.

"Burning cables."

That was what caused the dense black smoke all along thebanks of the Odaw. The boys burned TV and computer cables to get at the copperwires, which they sold locally for fifty pesewas per kilo, or about eighteencents per pound.

Ahead was a line of teenage boys that made Dawson thinkof an assembly line, only this was disassembly. The first boy was breaking openthe back of an old TV monitor using a rock. The second was degreasing somecables with a solvent. Farther along still, a cable-burning session wasbeginning. Five boys of ages ten to fifteen were crowded around a mass ofprepped cables. All from northern Ghana, they addressed Sly in rapid-fireHausa. Although Dawson wasn't fluent in the language, it was obvious they wereasking who he was. Sly's response seemed to satisfy them because they noddedand smiled.

"I tell them you're my friend," Sly explained.

"Where did you learn English?" Dawson asked.

"I was schooling at my hometown before my fathertold me to come to Accra with my uncle."

"Are you continuing school here?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"My uncle says he won't send me to school. He justwants me to sell copper and make money."

Dawson said nothing to that, for now anyway.

The Hausa boys used insulation foam as kindling and acigarette lighter to start the burn. Poking the cables with sticks brought theneeded rush of oxygen and created a miniature inferno with a blast of deadlyblack smoke. Even though he was upwind from it, Dawson caught a good whiff andbacked away slightly, thinking of the toxicity of the fumes. With his foot, heflipped over a piece of plastic from a computer monitor and found a label thatread school district of philadelphia. Junked, unusable equipment that the richcountries passed off as charitable donations ended up right here inAgbogbloshie.

"Ask them if any of them saw the dead person backthere or heard anything about it," Dawson said to Sly.

The boy obliged. His friends, intent on their task,replied briefly.

"They didn't see anything," Sly said."They haven't heard anything."

Dawson nodded. He hadn't expected much more than that.Fact was, if the dead person wasn't a friend of theirs or otherwise important,it just wasn't of that much interest to them. Someone died. So what?

"Let's go," Dawson said to Sly. A littlefarther along he put his hand on the boy's head like he was palming a soccerball. "Burning that stuff is dangerous. There's poison in the smoke andyou're breathing it inside your body. You understand?"

Sly nodded, but uncertainly. Dawson wasn't sure he reallydid get it. He ruffled his companion's short, wiry hair. "You're a goodboy, Sly. Is your uncle at home?"

Sly was hesitant about something.

"You don't like your uncle?" Darko asked.

"Yes, I like him," Sly said.

But the changed tone of his voice, broken up like ableat, told Dawson he wasn't telling the truth.

"Don't be afraid," Dawson said. "I onlywant to talk to him."

Roaming the open land bordered by the Ring Road on thewest and the edge of the Odaw River on the east were a few grazing horses and aherd of placid, foraging cows, brought all the way from the northernterritories by migrants who had lived as nomads. It was a bizarre mixing ofrural lifestyle with the urban slum. Only in Accra, Dawson thought. Only inAccra.

Deep within Agbogbloshie, Sly walked with easy assurance,as if floating over the rocky ground. He skipped nonchalantly across guttersfilled to overflowing with garbage encased in opaque, grayish black glop. Heducked under laundry hung out to dry on clotheslines crisscrossing like railwaytracks. He took narrow, abruptly swerving passages between rows of ricketyhomes constructed of wood that just begged for a conflagration.

Life went on here with the same inevitability it doesanywhere else. People worked and traded, children played, women got their nailsdone, men had their hair cut, and a group of shirtless teenage boys watchedsoccer on a communal TV.

Here and there, Dawson caught a whiff of marijuana, or"wee," as it was popularly known. From his nasal passages, it wentlike a blast to a pleasure spot inside his brain. He felt that tug of desirethat told him he had not yet conquered his vice. Five months completely clean.One day at a time.

People asked Sly who his companion was. He gave the sameanswer every time. "He's Darko, my friend." It was best that way.They didn't take to policemen. If casual queries about the corpse in the lagoonyielded little to no useful information, it was still more than Dawson wouldget if people knew he was a detective.

They passed a small mosque that stood out as one of thefew brick buildings in Agbogbloshie. A man inside was prostrate on his prayermat.

"There is my house," Sly said, slowing down andpointing. "Where those boys are playing."

Four teenagers were kicking and heading a soccer ballback and forth to one another without allowing it to touch the ground. A mansat in front of a windowless, eight-foot-square wooden shack raised off theground on short stilts.

"Is that your uncle?" Dawson asked.

"Yes."

Sly's uncle saw them approaching. For a moment he didn'tmove, but he finally rose to his feet as they came closer. He was frowning-thepuzzled kind of frown-and then he looked wary.

"Good morning?" He was average height withsquinting eyes. His hair was graying at the temples and retreating from hisdome forehead. He had tribal marks on both cheeks.

"Good morning, sir. My name is Darko Dawson."

"Yessah. I'm Gamel." His voice was like gravel.

Behind him, the door of his living quarters was ajar, andDawson caught a glimpse of a thin foam floor mattress as holey as Swiss cheese.

Recenzii

“Quartey cleverly hides the culprit, but the whodunit's strength is as much in the depiction of a world largely unfamiliar to an American readership as in its playing fair.”--Publishers Weekly Starred Review

“Kwei Quartey does what all the best storytellers do. He takes you to a world you have never seen and makes it as real to you as your own backyard. In Children of the Street he brings a story that is searing and original and done just right. Inspector Darko Dawson is relentless and I look forward to riding with him again.”—Michael Connelly

Praise for Kwei Quartey’s Wife of the Gods

“Fans of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency may have a new hero: Detective Inspector Darko Dawson.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Mystery fans have an important new voice to savor.”—Los Angeles Times

“Engrossing . . . a compelling cast of characters.”—Booklist (starred review)

“Full of suspense, humor and plot twists.”—Ebony

“Kwei Quartey does what all the best storytellers do. He takes you to a world you have never seen and makes it as real to you as your own backyard. In Children of the Street he brings a story that is searing and original and done just right. Inspector Darko Dawson is relentless and I look forward to riding with him again.”—Michael Connelly

Praise for Kwei Quartey’s Wife of the Gods

“Fans of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency may have a new hero: Detective Inspector Darko Dawson.”—The Wall Street Journal

“Mystery fans have an important new voice to savor.”—Los Angeles Times

“Engrossing . . . a compelling cast of characters.”—Booklist (starred review)

“Full of suspense, humor and plot twists.”—Ebony

Descriere

When the street children of Ghana begin falling victim to a chain of murders, Inspector Darko Dawson is once again called upon to investigate. Soon he's forced to come to terms with the brutal world of the urban poor, a world in which street children are forced to fight for their very survival.