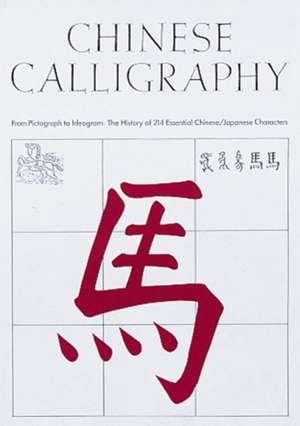

Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters

Autor Edoardo Fazziolien Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 aug 2005

Written Chinese can call upon about 40,000 characters, many of which originated some 6,000 years ago as little pictures of everyday objects used by the ancients to communicate with one another. To convey more abstract ideas or concepts, the Chinese stylized and combined their pictographs. For instance, the character for “man”—a straight back above two strong legs—becomes, with the addition of a head and shoulders and arms held sternly akimbo, the character for “official.” This book, modeled after a classic compilation of the Chinese language done in the 18th century, introduces readers to the 214 root pictographs or symbols upon which this writing system, whose rich complexities hold a wealth of cultural meaning, is based. These key characters, called radicals, are all delightfully presented in this volume, with their graphic development traced stage-by-stage to the present representation, where even now (in many of them) one can easily make out what was originally pictured—with the author’s guidance. Centuries ago, when the Japanese took up writing, they also adopted these symbols, though they gave them different names in their own spoken language.

Each of the 214 classic radicals is charmingly explored by the author, both for its etymology and for what it reveals about Chinese history and culture. Chinese characters are marvels of graphic design, and this book even shows the proper way to write each radical, stroke by stroke. Finally, there are also samples of each radical combined with other radicals and character elements to demonstrate how new characters are formed—some 8,000 have been added to the language since the eighteenth century. With all its expertly executed calligraphic illustrations and fascinating commentary, this book serves as an excellent introduction to Chinese writing and its milieu.

Each of the 214 classic radicals is charmingly explored by the author, both for its etymology and for what it reveals about Chinese history and culture. Chinese characters are marvels of graphic design, and this book even shows the proper way to write each radical, stroke by stroke. Finally, there are also samples of each radical combined with other radicals and character elements to demonstrate how new characters are formed—some 8,000 have been added to the language since the eighteenth century. With all its expertly executed calligraphic illustrations and fascinating commentary, this book serves as an excellent introduction to Chinese writing and its milieu.

Preț: 125.79 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 189

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.07€ • 25.04$ • 19.87£

24.07€ • 25.04$ • 19.87£

Cartea se retipărește

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789208705

ISBN-10: 0789208709

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 165 x 236 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.69 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 0789208709

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 165 x 236 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.69 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Recenzii

"If you are interested in the history of the development of Chinese characters this book is for you. The evolution of the characters is valuable for the language student as well as the artist. Understanding the development of the Chinese characters is a great help also to the student of Japanese. This is a wonderful book for the linguist as well as the artist." -- R. Ferris

Notă biografică

Edoardo Fazzioli was for ten years a correspondent in Hong Kong for an international agency. During that period, he also studied Chinese language and culture at Hong Kong University. He is currently a member of the Italo-Chinese Institute for Economic and Cultural Exchange, for which he has edited publications and catalogs. He has also written newspaper articles and scholarly pieces on Chinese life and civilization.

Extras

SHI: Family. The pictograph resembles a plant bobbing up and down on the water: one that grows and multiplies like the countless water lilies found in China. These start with a floating seed and grow surprisingly fast once they have found somewhere to put down roots. They bring to mind those nomadic groups that wander across the land trying to find a suitable place in which to settle, thus giving rise to the clan or family. In modern usage this character has lost its original meaning and acquired the role of a patronymic, as has happened with many other radicals. In classical language it was also used in the sense of development or multiplication.

LI: Village. A small group of houses, each of which-- in accordance with ancient law--occupied an eighth of the land, as it indicated in the upper part of the radical, albeit in reduced form. At the center was the common land occupied by the well. Apart from the meaning "village," this radical also signifies a measure of length, the li, equivalent to about 500 meters (c. 540 yards). The Great Wall in Chinese is the "Long Wall of the 10,000 li." Today it means "internal." In this sense of "internal," this character, joined to the one for "sea," means "Caspian Sea," the lake bounded by Russia and Iran. It also forms part of the Chinese word for the Italian unit of currency, the lira, but only as a phonetic transliteration, with no logical significance. A more precise and inspired derivation occurs in the word formed by this radical, in its sense of "internal," joined to the one for "spine": "fillet," the cut of meat that lies within the lumbar muscles next to the spine. Written next to the character for "hand," it indicates the part of the road to the left of a person driving a left-hand-drive vehicle: i.e. the middle of the road.

LI: Village. A small group of houses, each of which-- in accordance with ancient law--occupied an eighth of the land, as it indicated in the upper part of the radical, albeit in reduced form. At the center was the common land occupied by the well. Apart from the meaning "village," this radical also signifies a measure of length, the li, equivalent to about 500 meters (c. 540 yards). The Great Wall in Chinese is the "Long Wall of the 10,000 li." Today it means "internal." In this sense of "internal," this character, joined to the one for "sea," means "Caspian Sea," the lake bounded by Russia and Iran. It also forms part of the Chinese word for the Italian unit of currency, the lira, but only as a phonetic transliteration, with no logical significance. A more precise and inspired derivation occurs in the word formed by this radical, in its sense of "internal," joined to the one for "spine": "fillet," the cut of meat that lies within the lumbar muscles next to the spine. Written next to the character for "hand," it indicates the part of the road to the left of a person driving a left-hand-drive vehicle: i.e. the middle of the road.