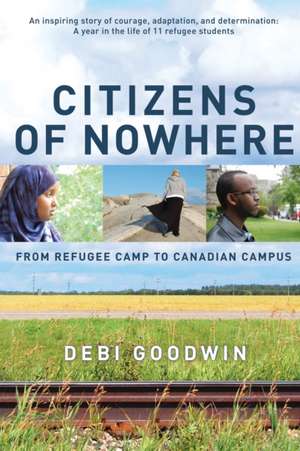

Citizens of Nowhere: From Refugee Camp to Canadian Campus

Autor Debi Goodwinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2011

"Most journalists have stories they never forget. This is mine."

When Debi Goodwin travelled to the Dadaab Refugee Camp in 2007 to shoot a documentary on young Somali refugees soon coming to Canada, she did not anticipate the impact the journey would have on her. A year later, in August of 2008, she decided to embark upon a new journey, starting in the overcrowded refugee camps in Kenya, and ending in university campuses across Canada. For a year, she recorded the lives of eleven very lucky refugee students who had received coveted scholarships from Canadian universities, guaranteeing them both a spot in the student body and permanent residency in Canada. We meet them in the overcrowded confines of a Kenyan refugee camp and track them all the way through a year of dramatic and sometimes traumatic adjustments to new life in a foreign country called Canada. This is a snapshot of a refugee's first year in Canada, in particular a snapshot of young men and women lucky and smart enough to earn their passage from refugee camp to Canadian campus.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 104.27 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.96€ • 21.69$ • 16.78£

19.96€ • 21.69$ • 16.78£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385667234

ISBN-10: 038566723X

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

ISBN-10: 038566723X

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

Notă biografică

Debi Goodwin is a documentary producer and a former CBC journalist. While at The National Debi produced documentaries from Latin America, Africa, China and Asia. The documentary "The Lucky Ones," which inspired this book, won the RTNDA's Adrienne Clarkson Award for best network program in 2008. Her work has also received a Gemini nomination and a Chris Award from the Columbus Film Festival.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

Out of the Sealed, Dark Room

Despite the shoving and the wailing at the bus stop in Hagadera refugee camp in northeast Kenya, the conductor for the Zafanana bus company tried to do his job that day. He herded, sometimes pushed, those with tickets onto the colourfully striped bus. It was almost nine in the morning and the bus was already an hour behind schedule. If the driver didn’t leave soon, he wouldn’t make it to Nairobi before dark. Expected and unexpected stops by Kenyan police to check travel documents could further delay the bus, adding to the urgency to begin the long drive west on the packed sand road.

Outside the bus, parents, friends and siblings blocked the entrance and surrounded those trying to get on board. Through an open window, a young man held onto his father’s hand. Inside, one young woman, not yet twenty, sobbed uncontrollably while another watched the most important woman in her life walk away. Eleven young students were among the passengers leaving on the Zafanana bus that day. They were leaving, perhaps forever, their families and others they loved, and the only world they had ever really known. It was August 16, 2008, a day they would remember for the rest of their lives.

Less than a week before the students zipped up their suitcases and boarded the bus, UNHCR did a head count in the three sprawling camps of Hagadera, Ifo and Dagahaley. Collectively, the camps in Kenya’s remote North Eastern Province are known as the Dadaab refugee camps. UNHCR officials knew that numbers were on the rise in the camps, knew that each month about 4,000 people were sneaking across the closed but poorly guarded Somali border less than one hundred kilometres away from the town of Dadaab, sneaking into Kenya to seek asylum from the violence in their homeland. On August 10, 2008, UNHCR found 206,639 refugees in Dadaab, up 20 per cent from the first day of the year. Dadaab was fast becoming one of the largest refugee camps in the world. Because of its location, the vast majority of both the new arrivals and the older residents in the camps were Somalis. Only about 3 per cent of the population in Dadaab came from places like Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia or Eritrea.

When UNHCR drew up the plans for the Dadaab camps in 1991, it foresaw a maximum of 90,000 people taking refuge there. Tractors cleared land previously used as rangeland for livestock, and over the next two years workers laid out plots for three camps encircling Dadaab, a small town near the equator where temperatures can reach 45 degrees Celsius in March. Drills bore through the semi-arid land to reach the precious water supply. That was the year Siad Barre’s dictatorship of Somalia ended in a bloody civil war. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis fled enemy militias and the destruction of their homes, fled on foot with whatever they could carry into Kenya, overwhelming the country’s ability to absorb refugees. Over the next few years the Kenyan government pushed as many refugees as it could find to the farthest, poorest corners of the country, into the camps of Dadaab in the northeast and Kakuma in the northwest, far away from the vibrant capital of Nairobi. The population of the Dadaab camps swelled as high as 400,000, more than four times the projection, before dropping well below 150,000 and then rising again.

Seventeen years after the Dadaab camps first opened, they had taken on a dispiriting feel of permanence, with tin-sheet schools, ill-equipped hospitals and even markets selling clothes and fresh food. care International provided elementary and secondary schooling and other programs designed to make life easier. It also sanctioned the markets, after entrepreneurial refugees wanting to fill idle time and their pockets asked for the space, often using money sent from relatives abroad to start their businesses.With no sign of peace in Somalia and few opportunities for resettlement, there was an unrelenting sameness to the days of those stuck in the camps. For most of the refugees, August 16, 2008, was just another day divided into equal parts darkness and light. Another day of stretching rations with whatever sugar or canned goods or vegetables they could afford to buy from the markets. Another day of lining up at communal taps to fill yellow jerry cans with water from deep inside the earth. Just another day marked not by nine-to-five jobs or by three daily meals, but by five prayers of Islamic submission. It is no wonder that Somalis have a word for the longing to be elsewhere, to earn resettlement to a third country. Buufis, they call it—a longing so strong it can make people lie about their identity, or drive them crazy, they say.

But before the chill of night left the air on that August day, before any hint of light tinged the sky, the family and friends of the eleven students leaving Kenya prepared for a very different day. Behind the kamoor—the high fences woven out of sticks that separate the compounds from each other—Somali families rose earlier than usual. Sisters and mothers lit kerosene lamps and poured the batter of flour, water and salt that had fermented overnight onto flat iron pans over freshly lit fires for thin pancakes known as anjera. They squatted or bent to toss unmeasured but exact amounts of loose black tea and crushed spices into aluminum pots of boiling water for the sweet, milky drink that added flavour and a burst of energy to every morning. In the Somali compounds, ten young people with few memories but these daily routines witnessed them for the last time. It is hard, they say, to make Somali men cry. Many did that day.

And in one compound in a corner of one camp where minority Eritreans and Oromos lived, the eleventh student, a single young man, looked around at his fellow Oromo teachers and began to weep, knowing he was the only one among them who would leave.

With more and more refugees flowing into the camps each day, the eleven students from Dadaab were going against the stream. They had given up their refugee papers, become subtractions from the count. They had all beaten the odds. Now they were off to Canada, a country they knew next to nothing about, to become permanent residents and university students, to be resettled in another country because they could not go back to their own and there was no future for them in Kenya beyond the sameness of life in the camps. What they knew about their third country, Canada, could fit on a single page. It was a cold place, they had heard, but all they knew of cold came from touching ice, and surely air couldn’t feel like that. And snow—what was it exactly? Something white that falls mysteriously from the sky. Looking at a foreigner’s picture of a patio table covered with a dome of January snow ten times thicker than the tabletop, one of the students asked, “Is that inside a house?”

They knew that Canada was a democratic country, and they had heard—and they prayed—that it was a tolerant place where they could practise their faiths with freedom. In school they had studied the politics of Kenya, Great Britain and even the United States. Canada, to no surprise, was nowhere to be found in the curriculum. Some thought there was a queen; others were sure there were elections. A couple of them knew there was a prime minister. None of that really mattered. Canada was not here. Canada would give them papers and let them move freely, study at universities and get jobs that could help their families.

Packed in suitcases ready to go were sweaters never worn, jeans, running shoes whiter than a fresh Canadian snowfall, photographs, hand creams and deodorants that surely couldn’t be purchased in Canada, sticks for cleaning teeth, hijabs and flowing scarves, Qu’rans and prayer mats. Some of the Somalis, those who could find them, had bought prayer mats with plastic compasses glued to them, compasses that would always point them in the right direction for prayer, toward the holy city of Mecca.

Dagahaley Refugee Camp

The Zafanana bus company had a garage in Dagahaley camp, where it began its journey to the capital just after dawn. A commercial company, it carried passengers with Kenyan identity papers and UNHCR travel documents to the city of Garissa, one hundred kilometres southwest of Dadaab, or on to Nairobi, five hundred long kilometres away. Those travelling all the way to the capital could reserve a seat for 1,000 Kenyan shillings, about $15 Canadian. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), overseers of the resettlement of refugees, had given each of the eleven students precisely 1,000 shillings to buy their tickets ahead of time from conductors who lived in each of the camps.

Before sunrise, the bus driver, the main conductor and the mechanic making the journey that day ate in a small lodge in Dagahaley where they had spent the night. Dagahaley is the most remote of the three Dadaab camps, seventeen kilometres north of the town of Dadaab and eleven kilometres from the nearest other camp, Ifo. Almost all of the population of Dagahaley is Somali and more than half had been nomads in their former lives. Walking long distances is something they are used to. Three students would board there: two Somalis, Mohamed Abdi Salat and Abdikadar Mohamud Gure, and a refugee from Ethiopia, an Oromo teacher known to the others as Dereje Guta Dilalesa.

There was barely enough light in the sky to make out the edge of the camp when twenty-three-year-old Mohamed started walking that morning. He lived with his mother, his twenty-one-year-old brother and young half-siblings in a compound in one of the remotest blocks of the remotest camp. At one end of the fenced compound, Mohamed and his brother shared a mud house. The house had two sleeping mats and a hole near ground level for ventilation. There, Mohamed, a fan of the BBC, often listened to a borrowed transistor for news about Somalia and about his favourite soccer team, Manchester United. A new radio would have cost almost $20, so he had settled for buying four D batteries for $1.50 every fifteen days. The cost and value of merchandise were concepts he understood well.

At the other end of the compound, his mother and the girls lived in a separate house. In between stood the family’s kitchen and sitting room, domed structures made of twigs and covered with bits of cloth, structures somewhat like the houses of the nomads they belonged to—houses built to be taken apart quickly. But there had been no need for that here. Mohamed and his family had lived in Dagahaley for almost seventeen years.

That morning Mohamed hired a neighbour with a wheelbarrow to carry his luggage for the twenty-minute walk to the bus stop. There was a light breeze as Mohamed’s mother and brother walked with him through a wide, open strip of sand along the edge of the blocks of housing. They passed the acacia tree that sheltered the homeless new arrivals to the camp. UNHCR had announced that month that Dagahaley had reached its capacity. There were no more plots of land left in the camp, so new arrivals spent day and night under the tree waiting to be registered to get food rations, waiting for somewhere better to go. As Mohamed passed the tree, the new Somali arrivals looked at him, in his clean khaki pants and fresh button-down shirt, as a stranger with a life worthy of envy.

To Mohamed the walk toward the centre of the camp that morning was like a dream. He tried not to think about what he was leaving behind. He forced himself to think ahead to the journey, to the room waiting for him at the Scarborough campus of the University of Toronto. Most of the information packages from Canadian students who would greet the eleven upon arrival had not found their way to the students or had been held for them in Nairobi. But Mohamed had received his, complete with a welcoming letter addressed to “Mr. Salat,” a brochure with pictures of the university president and the campus, and snapshots of the young people he would soon meet. While excited at the opportunity to study at such a beautiful university, Mohamed feared the changes he might undergo in Canada. He had learned from his friend Ibrahim, who had left the camp a year earlier, that many of the Somalis living in Toronto acted more like Canadians than Somalis. Just as the new arrivals from Somalia eyed him as someone different, he considered those Somalis who had changed in Canada to be different from him. Would the new country change who he was? He realized he might have to make small, insignificant changes in how he dressed and how he spoke, but he was determined not to stray from his religion or the basic rules of his culture.

Mohamed’s mother walked quietly beside her tall son with the kind smile. She was a woman accustomed to loss. Two of her husbands had already died. Mohamed’s father died three years before the war when Mohamed was a young boy. Her second husband died in the camp. A third husband, still living but suffering from hypertension, lived in another camp with his other family and was often too sick to visit her. She did not cry the morning Mohamed left, but after, whenever she walked the same route, she would think of the son who had gone so far away.

Her two sons were her breadwinners. They both taught in schools run by the aid agency care. Although the government would not allow refugees to take paid jobs, all the agencies gave “incentives” to those who worked as teachers, translators or assistants in the many projects in the camp. Together the brothers brought home a little more than $100 Canadian a month and helped raise the family above the poorest of refugees. Now all that responsibility would fall on the shoulders of Mohamed’s younger brother. Mohamed vowed to himself to send money home as soon as he could. He knew how much it would be needed. He could rattle off the costs of groceries at the market and list without hesitation the exact amounts of rations the World Food Programme distributed every fifteen days.

For the seven people in his compound, the rations were twenty-one kilograms of wheat flour, twenty-one kilograms of maize, seven cups of oil, seven bowls of dried beans or peas, seven bowls of dried soybean porridge and seven spoonfuls of salt. Sometimes there was more; sometimes there was less. There was never enough. And with new arrivals came new demands on the market goods from Somalia and eastern Kenya. A kilogram of meat could cost double the price of a year earlier, and sugar, a necessity for Somali tea, was on the rise too.

Mohamed was the first of the three students leaving that day to arrive at the Dagahaley bus stop. Abdikadar, another Somali student, twenty-two years of age, arrived soon after with his father and his brother. Abdikadar had fled Somalia with his family when he was five, after their farm was attacked by members of another clan and all the animals were stolen and some of his relatives killed. His mother was beaten so badly that she died during the long trek to the border. Both Mohamed and Abdikadar were popular teachers in the camp. The crowd around the bus stop grew as both teachers’ students came to bid them farewell.

It was the arrival of Dereje, as the other students knew him—or Dilalesa, as his Oromo friends called him—that caused the greatest stir. At twenty-five, Dilalesa was a handsome man with thick black eyelashes any Maybelline-wearing Western woman would kill for and muscles any sports club in North America would call well defined. He had come to the camp as a grown man just four years earlier. In Ethiopia he had studied some philosophy in university and had become a teacher. That was before the government accused the Oromo teachers of organizing student protests and he, along with nine other teachers fearing for their lives, had walked across the border from Moyale, Ethiopia, to the safety of Moyale, Kenya. There the teachers turned themselves in to the police.

In his four years in the camp, Dilalesa had set about creating a life as full and as healthy as possible. He’d used his knowledge of four languages to get a job as an interpreter for UNHCR, and with his incentive income he bought vegetables—potatoes, tomatoes and wedges of wilted cabbage. He was a vegetarian, but he found no other way to flavour his soups than the packets of Spicy OYO (an imitation of OXO) Beef Mix sold in the market.

When a German aid agency had handed out small, fast-growing neem trees to families to improve the environment and beautify their homes, most took one or two trees and planted them in corners of their compounds, opting to keep the dirt areas between the houses open so they could lay out mats to rest on or sit on to drink tea outdoors. But Dilalesa wanted a garden and took all the trees he could. On the day he left for Canada, the trees, with their fresh green leaves, stood taller than him, a small forest beside his house.

Inside the house, he’d painted the supporting centre pole an intricate orange and green pattern. On one wall he’d hung a computer-generated sign that read “Never Write Off Manchester United!!” Beneath it, on a wooden table, he’d laid out objects that sustained him: a red jersey—“Number 7 Dilalesa”—boxes of Colgate toothpaste, a car battery to run his radio/CD/cassette player, books, an issue of The Economist and rows of water and juice bottles.

The water and juice supported his sports habit. Dilalesa exercised religiously and had designed a rigorous rotation of activities for himself that included playing soccer for the minority team in the camp’s league and jogging in the bush, despite the heat and the oppressive air. He owned what had to be the most inventive pieces of sports equipment used in the camps. Managers of a care construction project had allowed him to take some concrete, with which he’d fashioned two barbells. To form each fifteen-pound barbell, he’d poured concrete into two large tins and joined the tins by inserting an iron bar. He’d also hoped to perfect his skills in the martial arts, but that would have to wait until he got to Canada.

Respect for the environment and respect for his own body were matters of faith for Dilalesa. Many of the Oromos of Ethiopia had converted to Islam or Christianity, but Dilalesa had stayed true to his traditional animist roots. To the camp’s uneducated, as he called them, he was a gaal, a pagan—or just another Ethiopian, a man from the country now fighting in Somalia. Some in the camp spat at him. Others avoided him in the food distribution lines or wiped the nozzles clean at the water stations after he used them. But none of the other students leaving for Canada treated him with such disrespect. With them, he could share his thoughts on the unfair treatment of the Oromos in Ethiopia. Some of them came from a clan of Somalis who lived in Ethiopia and had fought for freedom in the past.

Dilalesa was the chairman of the Oromos in all three camps. In return for his services, on the eve of his departure, his friends honoured him with a party and then, in the morning, followed him to the bus, openly crying over their loss. Dilalesa could not stop crying either. He hated the idea of leaving his friends behind in this hostile environment of harsh weather and devastating floods, a place “that spoils your life,” a place that forces you to “sleep on an empty stomach.” To leave his friends in such misery when he was getting a new life overwhelmed him with sadness. He would study philosophy again, this time at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, a country he felt certain would be democratic, peaceful and tolerant. And he had someone to go to the city of Saskatoon with: Abdikadar, the Somali student from the same camp, a young man who had become his friend.

A week earlier, Dilalesa and Abdikadar had walked hand in hand, as is customary for male friends in Africa, when they guided me around Dagahaley and took me to their homes. Dilalesa proudly showed off the Oromo Christian church near his house that he had helped build even though he wasn’t a Christian, a church made in the ubiquitous mud-and-dung style, with wooden rafters supporting the roof. On one cracked, yellow wall a wooden cross hung above a small pulpit. The church leader, a man who could have been a well-preserved sixty-year-old or a worn-out man in his forties, led us to white plastic lawn chairs outside and explained that Christian Oromos in Nairobi had donated the money for the church so the ten Christians in his congregation could worship together. The church leader was stuck here but hoped interviews for resettlement to Canada would turn into reality. Around the corner from the church stood a timber-and-twig mosque with a green tin door for the Oromos who were Islamic. “We all live in harmony here,” Dilalesa said.

He took us to a friend’s compound, where an Oromo woman was bathing her baby daughter in a plastic tub. The compound belonged to a young man who had been rejected for a scholarship to Canada for single students after it was discovered he was married and hadn’t disclosed the fact. “He couldn’t go to Canada,” Dilalesa said, “so he made the baby.”

The two young men led me outside Dilalesa’s compound and along narrow paths between the fenced compounds toward Abdikadar’s home. People strolled past us yelling or talking softly into their cellphones. With an unreliable mail service and only limited—and expensive—Internet in the markets, refugees in the camps had embraced the cellphone as a means of keeping track of each other and staying in touch with those in the outside world. The cheapest cellphone cost about $35 and represented a major outlay, but the charges to use one were low and easily controlled. The chip to connect to the service provider cost $1. Cards providing five to twenty minutes of calling time sold for 50 cents to $2. All incoming calls were free, and some people in the camps purchased phones with no intention of using them except to receive calls.

At his compound, however, Abdikadar sent someone to find his father in the market where he earned extra money for the family by carrying goods for businesses using the cart he owned. The man who soon appeared was a shorter, heavier version of Abdikadar, with the same high forehead, the same facial hair outlining his chin, although his was more of a beard than his son’s pencil-thin line. Through his son’s translation, Abdikadar’s father said he was happy that a visitor from Canada had come to see how the students lived and that he was grateful to Canada for accepting his son. All the family sat on a mat in their sitting room as they talked to me, making a point of asking Dilalesa to join them. Dilalesa, who played soccer with a team manned by minorities in the camp, nodded across the small room at a rival in his league, Abdikadar’s brother, who played on a team of Somalis.

A while later the two students guided me through another maze of passageways to the heart of the camp. We came out in the market near a “hotel,” a building much like the other wood-and-tin buildings in the market. There are no rooms in the hotels of Dadaab; Western visitors are not allowed to stay overnight in the camps. Instead, the hotels are the cafés and restaurants where people with a few extra shillings come. All the Dadaab market shops have a major advantage over the camps’ residents: electricity. With electricity they can offer Internet services, cellphone-charging and, in the case of the hotels, cold drinks from refrigerated cases. Without the odd treat of a cold drink from the hotel, the refugees had to make do with water they chilled in jerry cans wrapped in dampened cloths and stored in the shade.

There were few customers in the small hotel we entered. It was the middle of the afternoon and the market was quiet. Empty chairs at the long tables all faced a blank television mounted on one wall. On a table under the front window were jugs filled with a mixture of milk powder and juice, a drink known as attunza. A glass of attunza costs pennies, a bottle of Sprite or Fanta from the cooler more than double that but still less than a dollar.

We sat at a table with our soft drinks, surrounded by a few boys, listening to the hotel’s jazzy music, a change from the Somali music that pounded through most doorways. The young boys looked briefly at me, the Western woman who had come in the hotel’s front door, before turning back to each other. Abdikadar pointed to a second room at the back. “Women,” Abdikadar said, “come in the back door and go in there.” He said it without contempt or apology. It was just the way it was.

We talked about Saskatchewan. They had heard it was a prairie. Dilalesa said he feared the cold. One time he had travelled to Nairobi in the winter. “It was so cold,” he said, “I slept for a week.” Gently, I told him that the 10 degrees Celsius of a winter’s night in Nairobi was considered a nice spring day in Saskatoon.

Now at the bus station, as Dilalesa wept, someone, probably the conductor, grabbed his arm and led him to his seat so the bus could pull away from Dagahaley.

Ifo Refugee Camp

The sun had already risen as the bus driver, trying to make up for lost time, turned the Zafanana bus south and drove fast over the sand road to his next stop, Ifo camp, where the dust blows freely over a long, flat plain. Early in the morning the road was not as bumpy as it would be later in the day after the constant passage of aid vehicles turned it into corduroy ridges. Eleven kilometres later, as the camp came into sight, a high sign on rusty metal poles could be seen through the bus window. Beneath a blue metal sign identifying the site as Refugee Operations Ifo, six white metal plaques ran between the poles. The top plaque read: Government of Kenya. Then, in descending order: UNHCR, World Food Programme, care International in Kenya, MMZ/UNHCR/GTZ Partnership Operations and The National Council of Churches of Kenya. These were the same plaques mounted outside all the camps—constant reminders that life was possible here only through the generosity of others.

At Ifo there was even greater chaos and further delays. The bus picked up four more students: Abdi Hassan Ali, Abdirizak Mohamed Farah, Mohamed Hussein Ismail and the first young woman in the group, Halima Ahmed Abdille.

The night before, twenty-year-old Halima didn’t sleep. All day she’d walked through the narrow lanes of the camp between the walls of dried branches, stopping to saying goodbye to people she knew, listening to warnings that her culture and her religion would come under threat in the West, wondering if she would see any of these people again.

She had hoped to stop at the salon in the market during the day to have henna designs applied to her hands and her thin arms, but the line had been too long and she’d been too anxious to wait. Back at her compound she found it impossible to eat or even sit still, and she spent the evening hours visiting in the next block. Guests had come for a wedding celebration, and for four hours Halima answered all their questions about her imminent departure. It was midnight before she arrived home and she had her decorations yet to do. She finished her henna pattern of leaves at around two in the morning but still couldn’t fall asleep.

Halima was a statistical anomaly in the camp, a daughter with two living parents, both of whom had encouraged her to stay in school. A report written one year earlier by staff from Bates College of Lewiston, Maine, found that for every three boys in the primary schools run by care there were two girls. By secondary school, however, boys outnumbered girls four to one, and the remaining girls had trouble attaining marks as high as the boys’. It was Halima’s father, in particular, who had helped her beat those statistics. He had recognized her intelligence and ruled that in his compound none of his daughters would do kitchen duty in their last year of secondary school so they could concentrate on studying for their final examinations.

And Halima had grabbed at the opportunity to learn. On weekends and after class, students often gathered to study together in empty classrooms or in family compounds throughout the Dadaab camps. They knew that getting high grades in the exams for the Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education was the only ticket to higher education, the only chance at the few scholarships available to them. Halima had never wanted to be in a study group with girls. She loved sciences and mathematics and wanted to study with the more serious boys. She’d become the only girl in a study group with twenty male students from Ifo Secondary School. The group often gathered at her compound, sometimes studying all through the night before exams. When neighbours complained to her father that it was wrong for a girl to be with so many young men who were not her relatives, Halima spoke up for herself and her father listened. She had always accepted the place of women in the Somali world of Dadaab. She wore the sombre-coloured hijabs, accepted that men had the right to marry four wives and that young girls needed to remain chaste, accepted the certainty that women could never be leaders. But she believed in the right of girls to be educated, and she convinced her father that the study group was necessary if she was to succeed. In the end, she graduated secondary school with a B– average, high enough to apply for and win a scholarship at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Canada.

Six days before her departure, Halima invited me to a celebration in her honour. Friends and family filled the compound. The house Halima shared with her sister had been cleared out, a mattress shoved to one end, the walls draped with orange floral sheets. Thin sheet linoleum covered the dirt floor. With three adult children working for agencies, the family was well off—in refugee terms. Halima’s older brother rushed from group to group of guests taking pictures with an old camera before pulling out a video camera with fake wood panelling on its side, which he aimed at one person after another to get single shots, waving at people to stand still.

In the twig kitchen, Halima’s older sister laboured over a pot of boiling oil. From green plastic tubs filled with water, she scooped batches of potatoes cut like french fries and dropped them in to cook. Outside, women bent over the fire to heat water in kettles and aluminum pots. Plates and stainless-steel cups for serving drained on a small wooden cart.

Before the food was served I was summoned to another house to meet Halima’s father. He was eighty-five or thereabouts. Records of his birth date are long gone. An old man with a bright red hennaed beard was lying on one of two small beds thattook up most of the space in the close house. “He suffers from diabetes,” Halima said. Her father pulled himself up, and I was invited to sit across from him on the other bed. His thin legs were skirted in a traditional ma’awis and he wore a Somali patterned cap, but his green T-shirt sported a drawing of a running shoe and the word NIKE in pink letters. He told me he was happy his daughter was going to Canada. China, he said, is not a good place for Somalis. Neither is Italy. But in Canada there are human rights. He told me he was happy to pass his daughter on to me. I wondered if something had been lost in the translation and hoped he had meant to say that he was passing his daughter on to Canada.

When the feast was ready, women brought a large tin platter into the party room. The men sat around the platter on the linoleum floor and with bowed heads ate handfuls of rice, sliced tomatoes, boiled goat and chips, some the natural potato colour and some tinted red, stopping occasionally to pour spicy tomato sauce on their rice. When a platter that could feed six was set down in front of me, I protested, and the young female students were sent in to share it with me.

Throughout the party, Halima vacillated between a look of giddy hysteria and one of utter sadness, as though she would break into tears at any moment. There was a mercurial quality to her, but it was hard to tell if I was seeing something of her personality or just the enervating effects of a party day and the life-altering journey ahead of her. Before leaving, I touched her arm beneath the black hijab to say goodbye and tried not to show my surprise at how fragile I found her arm to be.

At four-thirty on the morning of her departure, it was time for Halima to get ready. She didn’t want to eat, didn’t want to bother with the photographer her brother had asked to take pictures. Instead, she took out the disposable camera she would carry to Canada and posed with her family against the sky that was still deeply blue in the early hours. Her last moments with her mother were captured on camera as they hugged and her mother’s strong hand pressed down on Halima’s head. Her mother had decided not to go to the bus stop with Halima, had decided it would be too emotional for both of them.

Halima’s father, younger sister, brother and cousin would take her in a van borrowed for the occasion; otherwise, it would be a thirty-minute walk to the bus stop—a difficult walk for her father. Today, for the pictures, he stood proudly, his right hand resting heavily on a cane. It was the hand with a missing finger, lost in an assault when the family was escaping Somalia. He wore a patterned ma’awis, a checked shirt, a shawl thrown around his shoulders to guard against the chill, and a multicoloured cap. He stared directly into his daughter’s camera with a smile that seemed to want to reassure the young woman who would examine the picture so far from home.

The other students from Ifo were at the bus stop before her. Among them was Abdirizak from Halima’s study group. He was twenty-four years old but had the bearing of someone far older. Neither of Abdirizak’s parents was with him that day. His mother had died in the camp from gunshot wounds she sustained in the fighting in Somalia, and his father had disappeared in the chaos of war. Abdirizak and his sister had lived in their uncle’s compound for eleven years, enduring the indignities of refugee life. Now Abdirizak was off to University College at the University of Toronto, where he planned to study economics, a field he’d chosen because he wanted to understand “why some people in the world are so poor when others have so much.”

Walking with Abdirizak days earlier on the wide lane through Ifo camp, commonly called “Ifo Highway,” I had decided he was an earnest man, more reserved than the other students. I could understand why the others saw him as serious enough, responsible enough, to be their leader. We talked about how different highways were in Canada and he asked if I would take him for a drive in Toronto. Along the way, trees known as “early grow” leaned over the sandy path providing shade in spots as we walked.

The early grow trees had been introduced to the camp by a German aid agency because they grew so quickly, but they had spread wherever they wanted, becoming a nuisance. Their thorns, Abdirizak told me, could cause illness and even kill livestock. Families passed us, pulling carts filled with plastic bags of rice or grains. Children rolled jerry cans of water back to their homes. Abdirizak walked down the road with graceful intent, like a king with no need to hurry, head held high, unsmiling. He told me he walked eight kilometres a day in the heat and the rain back and forth between his home and the school where he taught. When he was a student, he had used a bicycle because the teachers would close the doors when classes started, keeping tardy students out. When he was a teacher, he didn’t have the same worries of being late, and he’d grown tired of his years of riding the bicycle back and forth, so he walked to the school. As I walked slowly beside him, I thought there must have been times when he’d been especially late or had wanted to get out of the rain, but, adjusting to his calm, lion-like steps, I couldn’t imagine him breaking into a undignified run.

A group of old men, their heads wrapped against the sun, stopped Abdirizak and talked at him loudly, waving their hands at me, the white woman walking with him. I could hear only the guttural sounds of the Somali language and understood nothing. Abdirizak said a few words to the old men and walked away. Curious, I followed him and asked, “What did they say?” He answered quickly and somewhat slyly: “They asked who the woman was and why I didn’t introduce them. I told them you were a relative.” He said it with such a straight face that it took a moment for me to catch the sharp sense of humour behind his words.

Twenty-one-year-old Hussein, who was heading to Grant MacEwan College in Edmonton, wanted to study economics like Abdirizak. His father had died the year before and he hoped a degree in economics would guarantee him a good job so he could bring the rest of his family to Canada. That day his mother and brother came with him to the Ifo bus stop. Later, he would go over and over the moment he’d had to say goodbye, finally using his lessons from English composition to capture his unruly emotions on a sheet of lined paper:

The moment came where my heart skipped and my blood rised to its highest pressure. The last moment, the time I had to say goodbye to my mother, the factory of all my success, the only one in my life, the guide in my eyes. I gathered all my courage and had to face the challenge of saying goodbye to my mother. When I stood in front of her, tears trickled down my face, large hot drops of tears. My hands became limp. I could not move my body and the worse came when mother shed tears of love, tears of sadness and worry of seeing me for the last time. My older brother joined me and only added on to my worries when he clinged onto me.

On the sidelines in the Ifo market, near the bicycle rental shop where the Zafanana bus stopped, twenty-one-year-old Abdi squatted, in blue jeans and the thin black leather jacket he’d purchased in Nairobi for the cold Canadian climate. He chewed his nails and watched the scene around him with a worried expression. He had done all he could for his relatives and friends. He’d given away his houses and his cellphone and had organized a lottery to give away his bicycle, a luxury in the camp, but none of that did much to erase the guilt he felt at leaving everyone behind. Abdi hoped to study political science and economics, although there was something of the philosopher in him. “To be a refugee,” he mused, “is like living in a sealed, dark room.” Life had to be better out there than it was here in hot, dusty Ifo, where there was “no freedom of movement, no good jobs if you have an education, no work permitted even if you have the education. And sometimes you go without food.”

“I lived alone in the camps,” he said, “struggled without a mother and a father, without having family. I think I will find it easier in Canada.” Still, he could not erase the film of sadness that covered the day. To ease his guilt he told himself, “Some should escape outside and see what’s going on in the outside world.”

He would begin seeing that world at Huron University College in London, Ontario, although he still would not allow himself to believe he’d actually get there. He had waited until the last days to officially resign the position he held with care because nothing in life could be taken for granted. It was like a saying he’d heard: Man proposes. God disposes. And it was hard to forget what had happened to relatives still living in the camp, relatives who had made it as far as Nairobi in the resettlement process before their flight had been cancelled on September 11, 2001. There was a good reason the expression Enshallah, “God willing,” was repeated so frequently in the camps.

Abdi had become an orphan during the civil war when militia gunmen from a rival clan burst into the family’s home in Kismayo, Somalia, shooting wildly in the living room and killing both his parents and his three brothers. Only he and his sister escaped, but in the madness of the moment they became separated. In another time, on another continent, Abdi could have been the inspiration for a Charles Dickens novel. He’d shown the same pluck as Dickens’ orphans by fleeing through the back of the house and following neighbours on the exodus to Kenya, where people connected him with an uncle—his mother’s younger brother—in the camp. His sister made her way years later as a married woman to another camp, where she lived with her in-laws.

As a child, Abdi ate his meals with his uncle’s family, but when he was about twelve he started living in his own compound, sleeping in a brick house he helped build. The solitary life suited him. He was a very private person who wanted to keep his painful history to himself. When he felt lonely after a tiring day at work, he stopped by his uncle’s compound to listen to stories about his mother. He would miss his uncle’s stories.

After the flood of 2006 had washed away his first house, he’d built two more in his compound, a sitting room and a sleeping room out of mud and twigs, houses supported with the strongest timbers money could buy. Abdi could afford the houses and the bicycle, could afford to return his uncle’s kindness, because he received one of the highest incentives given to refugees: 5,700 Kenyan shillings, about $87.50 a month at the time. After secondary school he’d taken an incentive job with care, ending up in a group dealing with sexual and gender-based violence, where he gave talks about the hazards of female genital mutilation and mediated in domestic disputes. It was work he believed in, but it was work that often drew jeers from other men, who wondered why this young, skinny guy was interfering in traditional matters. “Feminist,” they called him. As if it were a bad word.

I met Abdi in the main care compound on my first day in Dadaab, one day before the other students came to meet me. We sat in an area between the agency buildings and the mess hall at a round picnic table covered with a round umbrella. Perhaps because he wore a beige baseball cap with the word care on it and told me people had nicknamed him “American” because he was lighter-skinned than some, or perhaps because he knew how to communicate so well, I went past the simple biographical questions I had planned for our first visit. There was a thoughtfulness to him, a certain gravity but also a willingness to engage and an eagerness to find humour in situations. Perhaps because of all that, I asked too much. He told me of his parents’ deaths. He told me what clan his family belonged to and what clan had killed them. I didn’t probe further, but I had already probed too much.

Two days later, I received an email from Ibrahim, his friend in Canada. Ibrahim advised me strongly not to ask questions about clan in the camps, where young people were trying to move past tribalism and where such questions might make them wonder who I really was. Ibrahim didn’t mention Abdi’s name. He didn’t have to: Abdi had been the only one I’d spoken to about clans.

When, days later, I went to visit Abdi in his home, he greeted me graciously and laughed with good humour when I pointed out how much taller his nephew was than him. As we walked in the camp, I told him I would not ask any more questions about clan while I was there. He seemed relieved. It was a lesson for me, not just in sensitivity, but in awareness of how quickly news spreads among Somalis, wherever they are.

The morning of his departure, Abdi started walking to the bus stop before sunrise to greet his friends there and to make sure he was on time. Now he squatted, nervously waiting. The bus was late. When it finally came at seven-thirty, he got on board, the first step of a journey where so much could still go wrong. The conductor tried to keep order, to find the passengers among the forty or so people crowded around the bus. When Mohamed from Dagahaley descended to stretch, he had to convince the Ifo conductor he was a passenger because he had left his ticket on the bus. Fortunately for him, the main conductor on the bus recognized him. Finally, with most of his passengers on the bus, the conductor, in frustration, yelled at a tearful Halima to leave her family and pushed her toward the door.

The Town of Dadaab

Before the Zafanana bus could travel to the last refugee camp, Hagadera, it had to stop in the town of Dadaab, where it would go through the first of half a dozen checkpoints on the drive to Nairobi. The students dreaded the checkpoints and feared the Kenyan police who ran them. It was not uncommon for the police to reject travel documents that were perfectly legitimate or to take a person’s papers, hide them and claim the passenger had nothing. “They are hard and they can do what they want,” Mohamed said.

Abdi anticipated problems. One time he had been travelling with Halima when she was hassled because her picture was fuzzy. And another time he had been held even though he had documents that allowed him to go to Nairobi for the TOEFL, the exam that demonstrated the proficiency in English required for his scholarship. The police had finally let him take a later bus, but he could never relax near checkpoints after that.

The Dadaab checkpoint didn’t scare any of them nearly as much as the one they’d cross later at the Tana Bridge, a checkpoint that divided the region inhabited by Kenyans who were ethnic Somalis from what was known as the “real” Kenya. Abdi recalled a sign at the bridge in Swahili that translated into English as “Have a Safe Journey,” but he didn’t believe the police meant it. At various times students had been pulled from buses at the checkpoint and taken to the police post next door, for no apparent reason, before being suddenly released.

If the police didn’t hold them back, they might try to bribe them. Abdi and the others knew all too well the code words the police used to make things go more smoothly, words like “chai,” or “soda,” which were really a request for cash. Or, in Swahili, the police might ask for kitu kudogo, meaning “a small thing.” The bus drove six kilometres east to the town of Dadaab, travelling past scrubby bushes with leaves grey with dust and the tall, noble acacia trees off in the distance, past the large red termite mounds that looked like unfinished sculptures. Outside of the town, the bus passed fields of garbage where torn bits of plastic hung from the ends of thorny bushes, and goats and marabou storks competed for slim pickings. The ungainly storks, known by aid workers as “rats of the sky,” are scavengers, survivors, and they are everywhere. Atop acacia trees their enormity mocks all sense of proportion. On the sides of the road, they dwarf young girls wrapped in red or yellow cotton. In the middle of the road, they stop traffic before raising oversized wings and awkwardly flying off.

For the last time, the students passed Dadaab Primary School with its sign that read “Kick aids out of Dadaab” and its other sign from the Danish Refugee Council, listing all the good it had done for the school in providing desks, toilets, girls’ uniforms and sanitary belts. Electricity and water flowed in the primary school, courtesy of care. Over the years, the agencies had given more and more help to the local community, which had become more and more vocal about the refugees in their midst using their resources and getting better education and cleaner water.

The bus slowed on the main strip in Dadaab to avoid the dips in the road and the shoppers who walked by the tin shops and the Al Rhama and Blue Nile hotels.

There is little to recommend the town of Dadaab to visitors. Announcements for positions with the major employers in the region, the aid agencies, insist that applicants “have prior knowledge of living conditions in Dadaab” and warn that “during the rainy season, mosquitoes, snakes, scorpions, bugs and insects are in abundance.” Even for types who like their travel rough, it’s hard to find Dadaab in any guidebooks. A search online through the Lonely Planet site might ask if you meant Madaba, in Jordan, and offer nothing on Dadaab. The town sits less than one degree north of the equator, too far away for a marker that tourists could pose by with smiling faces and thumbs up, and the barren landscape, often frequented by shiftas, or bandits, invites neither picture taking nor hikes. As small and as remote as Dadaab looks to the outsider, it is less small and less remote than it was before the camps came. A population of a few thousand in the early 1990s has more than tripled because of the employment opportunities created. Thanks to the camps, roads in the area are better maintained and communication with the rest of the country and the world has improved. In 2004, Kenya’s mobile phone company, Safaricom, extended coverage to the area.

On the left, the bus drove past the steel gate and the razor-wire fencing of the main aid compound, and on the right, it passed the Islamic Centre and Dadaab Secondary School, with its library and laboratory funded by UNHCR. It came to a stop at the checkpoint at the edge of town, where police in camouflage uniforms checked the identity papers of the Kenyan nationals and the students’ travel documents. That day there was no problem, and Abdi believed it was because there was safety in numbers. Seven students were already on board and they all yelled that they were going to Canada to study. The guard lifted the spiked yellow metal roadblock and allowed the bus to pass into the open road ahead.

Hagadera Refugee Camp

Ten kilometres southeast of Dadaab, the bus stopped at Hagadera camp, known for the red sand that makes walking difficult and riding a bike impossible. Here it picked up the final four Somali students: Aden Sigat Nunow, Muno Mohamed Osman, Siyad Adow Maalim and Marwo Aden Dubow.

It was a good thing the bus was late that morning, because Muno was having trouble leaving her compound. “There was no moving,” she said. She stood between the tin door and the goat’s twig shelter of her home in Block B5 thinking up excuses each time her father called from the bus stop to hurry her along. Muno could count on one hand the number of times she had slept away from this compound, away from her sister and mother. Just shy of twenty, with a pouty, plump, beautiful face, she was the youngest student leaving that day, perhaps too young for such an unimaginable departure. She assumed life would be better in Canada than it was here, but everything she had learned about life had happened here, in this compound, in this camp. She had read her first books here, anything she could get her hands on—Swahili books, English books, joke books, it didn’t matter. She had read collections that had intrigued her, like the stories of Sherlock Holmes, to her a real detective. She had read great books, such as The Headsman and The Kite Runner, the latter a gift from a Kenyan teacher who had recognized her hunger for reading. In this compound Muno had decided she wanted to be a writer who would tell the stories of refugees and of her religion. She knew she had to leave to do that. She knew there were more books out there—a whole library of books at the Mississauga campus of the University of Toronto—knew she had huge holes in her knowledge she could never fill here. And yet the price she had to pay for the opportunity to get that knowledge seemed so high. She had never suffered the obsession of buufis. It was not longing for resettlement that finally made her move from that doorway, not even her personal longing for endless shelves of books, but the knowledge that this opportunity, the chance to study at a university in Canada, would give her the means to help her family.

In Block C1, near the Hagadera market, Marwo, the third female student leaving that day, had already said her goodbyes to her aunt, the woman who had sheltered her after her parents died in the conflict and her grandmother died later in the camp. It was her aunt who had stepped in to care for her and who called her “daughter.” There was nothing sentimental about the woman. “Hard,” Marwo called her aunt, meaning it as a compliment. Marwo’s aunt was divorced, a midwife and a woman who believed in getting on with life. She had not brought Marwo into the world, but she was determined to send her out into it, even if it meant losing her best companion in a lonely place.

A week earlier, I had sat across from Marwo’s aunt in the centre of her compound. The acrid smell of burning garbage wafted over the walls. We sat—me on the only stool in sight, her on a jerry can—smiling at each other and making small talk through Marwo’s translations. I expressed admiration of her work as a midwife. The aunt expressed joy over her niece’s move to Canada. We smiled again at each other. A few drops of rain fell from the sky and Marwo’s aunt rushed me into her house along with Marwo, Muno and a young Kenyan teacher, Catherine Kagendo, who had accompanied us around Hagadera camp. Marwo offered tea. I requested mine without milk because of the stories of Westerners sickened by unpasteurized African milk.

The rain stopped within minutes, but we stayed in the darkened room drinking the clear, sweet tea, sitting on mattresses that were wrapped in patterned sheets. There was a quiet intimacy to the moment, the noise of the camp muffled inside the house, the absenceof men freeing the women to talk openly. Muno and Marwo spoke about how girls in the camp kept away from men during their periods, how girls stopped playing sports with boys when they reached puberty. care, they said, had delivered sports outfits for girls that totally covered their bodies, but people had scorned the girls who wore them. They said that care had been more successful when organizers had found an enclosed area where girls could play together, because girls and women like their privacy from men. Privacy is everything. Marwo and Muno explained that there are some women who cover their faces for extra privacy in the camps, although others do it to avoid the dust—that there is nothing in the religion that demands the face be hidden. Muno, in particular, worried that privacy would be harder to find in Canada.

The young women wanted to know if there were dogs in Canadian homes. When I said there were, Marwo asked, “Will they hurt us?” I said that they would not if they were treated well and that most dogs were treated like companions in Canadian homes. I told them about dogs trained to guard property but said they wouldn’t have to come in contact with them. Muno—the daughter of a man who is both an imam, the prayer leader at his mosque, and a sheikh knowledgeable in Islamic teaching—explained to me that any contact with a dog is considered a heavy impurity. If a dog touched her, she said, she would have to wash her hands seven times before praying. She went on to list the mid-level impurities of blood, pus and the urine of an adult or a baby girl. The least offensive impurity, she said, is the urine of a baby boy.

Throughout the visit, Muno constantly busied herself, fingering the Swahili novel she carried with her as though she wanted to get back to it, checking her cellphone and reading a newspaper that Marwo had found and kept for her. Marwo liked to read too but not as much as her friend Muno did. Muno searched the paper for words she didn’t know. When she came across the word lingerie in a joke, she asked me if it was just the underwear part or the top as well.

That morning, she had kept us all waiting, phoning several times to say she was on her way, admitting, after arriving an hour late, that she had been reading her novel while she was cooking breakfast and had lost track of time. She did, however, get through most of the novel.

We came out of the house to the bright midday light and the chirping of chickens caged by Marwo’s aunt for their healthy eggs. Children were running everywhere, some from the families of new arrivals now enlarging the population of the compound, and I suddenly understood the desire to retreat into those houses. On the way out of the compound, Marwo ran up to me with a message from her aunt. I should take milk in my tea. It was the health advice of a midwife to another woman.

Marwo and Muno guided me toward Hagadera market, where they had to do some final shopping for their trip. On the way, we passed a donkey cart piled high with wood. Marwo told me the load, a three-month supply, cost 1,000 shillings, a price they had to pay. The ration of wood allotted to them as refugees was insufficient for all the cooking needs of the compound and her aunt wouldn’t allow Marwo to gather wood in the bush because women who foraged there were often raped. As we walked, Catherine, the Kenyan teacher, and I wore scarves wrapped loosely around our heads. Catherine told me children would throw stones at uncovered women. Even with the scarves, she admitted, they sometimes still did. Marwo and Muno both wore the hijab, the ubiquitous outfit for women and school-aged girls: a circle of cloth with an opening for the face, it flowed loosely to the knees and was worn over a long skirt. When I stumbled in a rut of the sandy laneway, I heard a chorus of “sorry,” from Muno and Marwo. By then I had heard the word used by most of the students in the camps. Whenever I brushed away a mosquito or my shirt caught on a loose fence twig or I told them about something that had gone wrong in my day, they said “sorry,” very softly, with a depth of empathy I found moving. I wanted to tell them they would fit in with Canadians, who were reputed to use the word “sorry” even when they were not at fault, but I couldn’t figure out how to explain the joke.

In Hagadera market, we passed a shop with bolts of material and a sewing machine outside. Marwo said that a hijab, like the one she wore in a washed-out lavender colour, cost 250 shillings—200 for the material and 50 for the sewing. At another shop she pointed out the bottles of powdered henna they could mix with water to decorate themselves for Muslim holidays. The bottles varied in price from 10 to 50 shillings for one of the highest quality. But today they both needed new prayer mats. In Marwo’s case there was some urgency to find one with a compass, since she would have to pray as soon as she got to her room in Victoria and wasn’t sure anyone at the university would know the direction to Mecca. Muno was looking for a plain mat; a student from Dadaab was already at her campus in Mississauga and could help her face Mecca. As we walked past stalls filled with stacks of flip-flops and rolls of linoleum, Muno said that memories of the market would haunt her. She would miss its liveliness and the pleasure of spending time there with her friends. The two young women pointed out the shop where they usually bought their henna. The saleswoman, her face covered, saw our interest and pushed the shampoos and creams. She had the gift of a born salesperson, teasing the young women and joking with me that Marwo and I looked alike, challenging again my idea of who had a sense of humour and who did not.

Most of the stalls were sold out of the mats with compasses. At one, Muno picked up a rather gaudylooking mat in bright orange and greens from a pile of mats without compasses and asked our opinion. Both Marwo and I shook our heads, and Muno decided on another one in various shades of blues, arguing with the salesman until he lowered the price from 300 shillings to 270. Catherine said the bargaining was tougher in Nairobi. Muno responded, defending her home, saying that there were not as many choices here in the camp market. Finally, at another stall, Marwo found a mat with a white plastic compass. The saleswoman demanded 550 shillings and wouldn’t take less than 500, a price Marwo considered too high. Her friend Siyad had paid much less for his. In the end she decided to buy a plain mat and asked me if I could email the young woman who would be meeting her in Victoria to find out which direction she should face for her prayers.

In her years living with her aunt, Marwo had learned how to be sensible. She had chosen to study international relations at the University of Victoria because it seemed to be a “marketable” field, but she was keeping her options open. Maybe once she was at the university she’d find another field that would give her what she wanted: an education, a good job and money. When she had all three, she knew, her life would change.

The compound Marwo and her aunt shared was a busy one with little space between the buildings that housed other relatives, including the new arrivals from Somalia with nowhere else to live. Marwo’s aunt was not a woman to turn people away. That morning, Marwo’s aunt had risen early from the house she shared with her niece to prepare a solid breakfast. That taken care of, she set off for work at the hospital, leaving it to other relatives to wait with Marwo at the bus stop.

In his home in B5, twenty-three-year-old Siyad had also said his most important goodbye. His father, the constant in his life, had a religious class to attend and couldn’t go with him to the bus. Siyad’s stepmother, sister and friends walked with him to the bus stop. Seeing all the crying faces around him, Siyad started to cry too until a friend asked him, “Why should you cry? This is not the end. Your parents will still be here.” And he realized he could come back. If he became a doctor, as he hoped, he could return and care for the sick in Dadaab or in Somalia. He imagined the photo from the University of British Columbia’s website, and this buoyed his spirits. It showed a young man and a young woman sitting in opposite directions quietly reading. It was sunny outside. This, he was sure, was what Canada would be like.

Aden was also thinking of becoming a doctor. It was a profession that topped his list of choices, at least, right below pilot. At twenty-one, Aden had no experience with planes—had never flown in one—but he had seen airplanes in movies, and he had watched them fly high over the camp’s air space. And that was enough to fuel his ambition. To some, his method of choosing a career might seem odd, but for Aden it made sense. His face shone with curiosity and ambition. Highly intelligent, he had graduated in 2006 with an A– average as the top student in Hagadera and tied for best in the region.

Aden described one of his hobbies as travelling, which, at first glance, seemed another quixotic notion for someone who had grown up in a refugee camp. But Aden was a guy who knew how to work around restrictions. He’d repeatedly visited an uncle in the Nairobi suburb of Eastleigh, using a student card from a high school there to travel back and forth. In Eastleigh he could receive tutoring in chemistry and Swahili and ensure that his grades in the final examinations were the best they could be. One time, he had gone to Nairobi for a mathematics competition and had travelled to nearby Lake Naivasha, where he’d seen vast flocks of flamingos. He assumed he would be able to expand his hobby of travelling once he got to the West.

He was a man who thought big, who couldn’t wait to get out of the sealed room permanently and play. Even his cellphone expressed his desire for more. It rang with the title of Jamaican rapper Sean Paul: “(When You Gonna) Give It Up to Me.” Aden had bought one of the most expensive cellphones he could find, a Sony Ericsson K750i for which he’d paid $200, because he liked “fancy phones.”

Aden wanted it all and he wanted it fast: cars and cameras, life in a big city like Toronto. He felt sure he would find people to help him in Canada, maybe someone who would buy him an airplane ticket so he could visit his mother the following summer. Ironically, the big, confident guy with the biggest ideas was headed to a university in the smallest city: Brandon, Manitoba.

In Hagadera, Aden was the man of his household. His father, who had lived separately from the family before the war, had disappeared in the fighting. His older sister’s husband lived in New Zealand and sent money back to support his wife and their children in the camp. Both women pampered Aden: his sister had taken him to Nairobi to buy his clothes and two big suitcases for Canada; his mother had baked cookies for his journey. That morning the two women cried as they walked with Aden to the bus stop near the Hagadera police station. Although he felt sad too, Aden wouldn’t let himself cry. “I was trying to be hard,” he said later, “but I was crying inside.”

When the bus arrived, crowds surrounded it, once again blocking the door and frustrating the conductor, who was still trying to make up some of the time they’d lost. The four students had to force their way inside. The bus was so late leaving that Marwo’s aunt had time to return from her morning work and Siyad’s father from his religious class before the driver pulled away. Siyad, already seated near the back, reached through a window and took his father’s hand one last time. Not far from him, Muno cried inconsolably. Like a chain reaction, the sound of her sobs set off Halima and Dilalesa. As the bus drove off and Marwo watched her aunt turn away and walk home, all her bright hopes for change were doused by the singular thought that she should have stayed.

The Zafanana bus that carried the Dadaab eleven out of their sealed box that day was brown with a zigzag design of red, orange and yellow stripes on its side. Later, none of the students could recall exactly what that bus looked like. It could have been pale blue. It could have had green stripes or maybe green and red stripes. They had paid little attention. Their eyes had been focused first on the faces of families and friends and later on the land they might never see again.

From the Hardcover edition.

Out of the Sealed, Dark Room

Despite the shoving and the wailing at the bus stop in Hagadera refugee camp in northeast Kenya, the conductor for the Zafanana bus company tried to do his job that day. He herded, sometimes pushed, those with tickets onto the colourfully striped bus. It was almost nine in the morning and the bus was already an hour behind schedule. If the driver didn’t leave soon, he wouldn’t make it to Nairobi before dark. Expected and unexpected stops by Kenyan police to check travel documents could further delay the bus, adding to the urgency to begin the long drive west on the packed sand road.

Outside the bus, parents, friends and siblings blocked the entrance and surrounded those trying to get on board. Through an open window, a young man held onto his father’s hand. Inside, one young woman, not yet twenty, sobbed uncontrollably while another watched the most important woman in her life walk away. Eleven young students were among the passengers leaving on the Zafanana bus that day. They were leaving, perhaps forever, their families and others they loved, and the only world they had ever really known. It was August 16, 2008, a day they would remember for the rest of their lives.

Less than a week before the students zipped up their suitcases and boarded the bus, UNHCR did a head count in the three sprawling camps of Hagadera, Ifo and Dagahaley. Collectively, the camps in Kenya’s remote North Eastern Province are known as the Dadaab refugee camps. UNHCR officials knew that numbers were on the rise in the camps, knew that each month about 4,000 people were sneaking across the closed but poorly guarded Somali border less than one hundred kilometres away from the town of Dadaab, sneaking into Kenya to seek asylum from the violence in their homeland. On August 10, 2008, UNHCR found 206,639 refugees in Dadaab, up 20 per cent from the first day of the year. Dadaab was fast becoming one of the largest refugee camps in the world. Because of its location, the vast majority of both the new arrivals and the older residents in the camps were Somalis. Only about 3 per cent of the population in Dadaab came from places like Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia or Eritrea.

When UNHCR drew up the plans for the Dadaab camps in 1991, it foresaw a maximum of 90,000 people taking refuge there. Tractors cleared land previously used as rangeland for livestock, and over the next two years workers laid out plots for three camps encircling Dadaab, a small town near the equator where temperatures can reach 45 degrees Celsius in March. Drills bore through the semi-arid land to reach the precious water supply. That was the year Siad Barre’s dictatorship of Somalia ended in a bloody civil war. Hundreds of thousands of Somalis fled enemy militias and the destruction of their homes, fled on foot with whatever they could carry into Kenya, overwhelming the country’s ability to absorb refugees. Over the next few years the Kenyan government pushed as many refugees as it could find to the farthest, poorest corners of the country, into the camps of Dadaab in the northeast and Kakuma in the northwest, far away from the vibrant capital of Nairobi. The population of the Dadaab camps swelled as high as 400,000, more than four times the projection, before dropping well below 150,000 and then rising again.

Seventeen years after the Dadaab camps first opened, they had taken on a dispiriting feel of permanence, with tin-sheet schools, ill-equipped hospitals and even markets selling clothes and fresh food. care International provided elementary and secondary schooling and other programs designed to make life easier. It also sanctioned the markets, after entrepreneurial refugees wanting to fill idle time and their pockets asked for the space, often using money sent from relatives abroad to start their businesses.With no sign of peace in Somalia and few opportunities for resettlement, there was an unrelenting sameness to the days of those stuck in the camps. For most of the refugees, August 16, 2008, was just another day divided into equal parts darkness and light. Another day of stretching rations with whatever sugar or canned goods or vegetables they could afford to buy from the markets. Another day of lining up at communal taps to fill yellow jerry cans with water from deep inside the earth. Just another day marked not by nine-to-five jobs or by three daily meals, but by five prayers of Islamic submission. It is no wonder that Somalis have a word for the longing to be elsewhere, to earn resettlement to a third country. Buufis, they call it—a longing so strong it can make people lie about their identity, or drive them crazy, they say.

But before the chill of night left the air on that August day, before any hint of light tinged the sky, the family and friends of the eleven students leaving Kenya prepared for a very different day. Behind the kamoor—the high fences woven out of sticks that separate the compounds from each other—Somali families rose earlier than usual. Sisters and mothers lit kerosene lamps and poured the batter of flour, water and salt that had fermented overnight onto flat iron pans over freshly lit fires for thin pancakes known as anjera. They squatted or bent to toss unmeasured but exact amounts of loose black tea and crushed spices into aluminum pots of boiling water for the sweet, milky drink that added flavour and a burst of energy to every morning. In the Somali compounds, ten young people with few memories but these daily routines witnessed them for the last time. It is hard, they say, to make Somali men cry. Many did that day.

And in one compound in a corner of one camp where minority Eritreans and Oromos lived, the eleventh student, a single young man, looked around at his fellow Oromo teachers and began to weep, knowing he was the only one among them who would leave.

With more and more refugees flowing into the camps each day, the eleven students from Dadaab were going against the stream. They had given up their refugee papers, become subtractions from the count. They had all beaten the odds. Now they were off to Canada, a country they knew next to nothing about, to become permanent residents and university students, to be resettled in another country because they could not go back to their own and there was no future for them in Kenya beyond the sameness of life in the camps. What they knew about their third country, Canada, could fit on a single page. It was a cold place, they had heard, but all they knew of cold came from touching ice, and surely air couldn’t feel like that. And snow—what was it exactly? Something white that falls mysteriously from the sky. Looking at a foreigner’s picture of a patio table covered with a dome of January snow ten times thicker than the tabletop, one of the students asked, “Is that inside a house?”

They knew that Canada was a democratic country, and they had heard—and they prayed—that it was a tolerant place where they could practise their faiths with freedom. In school they had studied the politics of Kenya, Great Britain and even the United States. Canada, to no surprise, was nowhere to be found in the curriculum. Some thought there was a queen; others were sure there were elections. A couple of them knew there was a prime minister. None of that really mattered. Canada was not here. Canada would give them papers and let them move freely, study at universities and get jobs that could help their families.

Packed in suitcases ready to go were sweaters never worn, jeans, running shoes whiter than a fresh Canadian snowfall, photographs, hand creams and deodorants that surely couldn’t be purchased in Canada, sticks for cleaning teeth, hijabs and flowing scarves, Qu’rans and prayer mats. Some of the Somalis, those who could find them, had bought prayer mats with plastic compasses glued to them, compasses that would always point them in the right direction for prayer, toward the holy city of Mecca.

Dagahaley Refugee Camp

The Zafanana bus company had a garage in Dagahaley camp, where it began its journey to the capital just after dawn. A commercial company, it carried passengers with Kenyan identity papers and UNHCR travel documents to the city of Garissa, one hundred kilometres southwest of Dadaab, or on to Nairobi, five hundred long kilometres away. Those travelling all the way to the capital could reserve a seat for 1,000 Kenyan shillings, about $15 Canadian. The International Organization for Migration (IOM), overseers of the resettlement of refugees, had given each of the eleven students precisely 1,000 shillings to buy their tickets ahead of time from conductors who lived in each of the camps.

Before sunrise, the bus driver, the main conductor and the mechanic making the journey that day ate in a small lodge in Dagahaley where they had spent the night. Dagahaley is the most remote of the three Dadaab camps, seventeen kilometres north of the town of Dadaab and eleven kilometres from the nearest other camp, Ifo. Almost all of the population of Dagahaley is Somali and more than half had been nomads in their former lives. Walking long distances is something they are used to. Three students would board there: two Somalis, Mohamed Abdi Salat and Abdikadar Mohamud Gure, and a refugee from Ethiopia, an Oromo teacher known to the others as Dereje Guta Dilalesa.

There was barely enough light in the sky to make out the edge of the camp when twenty-three-year-old Mohamed started walking that morning. He lived with his mother, his twenty-one-year-old brother and young half-siblings in a compound in one of the remotest blocks of the remotest camp. At one end of the fenced compound, Mohamed and his brother shared a mud house. The house had two sleeping mats and a hole near ground level for ventilation. There, Mohamed, a fan of the BBC, often listened to a borrowed transistor for news about Somalia and about his favourite soccer team, Manchester United. A new radio would have cost almost $20, so he had settled for buying four D batteries for $1.50 every fifteen days. The cost and value of merchandise were concepts he understood well.

At the other end of the compound, his mother and the girls lived in a separate house. In between stood the family’s kitchen and sitting room, domed structures made of twigs and covered with bits of cloth, structures somewhat like the houses of the nomads they belonged to—houses built to be taken apart quickly. But there had been no need for that here. Mohamed and his family had lived in Dagahaley for almost seventeen years.