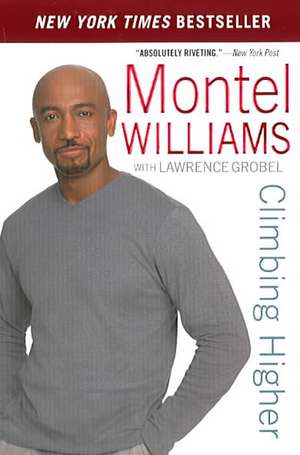

Climbing Higher

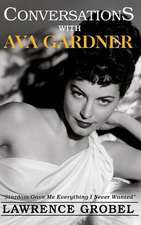

Autor Montel Williams, Lawrence Grobelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2004

In 1999, after almost twenty years of symptoms, Montel Williams, a decorated naval officer and Emmy Award-winning talk show host, was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. He was struck with denial, fear, depression, and anger, and now he's battling back. Graced with strong values, courage, and hard-won wisdom, he shares his insights in this powerful book on the divergent roads a life can take, and recounts how he rose to meet the challenges he's faced. Surprising, searing, and deeply personal, Climbing Higher is as honest and inspiring as its author.

Preț: 179.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 270

Preț estimativ în valută:

34.42€ • 35.50$ • 29.13£

34.42€ • 35.50$ • 29.13£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-06 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780451213983

ISBN-10: 045121398X

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 139 x 205 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: New American Library

ISBN-10: 045121398X

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 139 x 205 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: New American Library

Notă biografică

Montel Williams has established himself as a top player in the competitive daytime talk show arena since his debut in 1991. He is also a decorated former Naval intelligence officer and a renowned motivational speaker, author, actor, and philanthropist. He is the creator of The Montel Williams MS Foundation.

Lawrence Grobel has written for many publications and has interviewed everyone from Truman Capote, Marlon Brando and Barbra Streisand to Halle Berry and Drew Barrymore. The author of The Art of the Interview, Grobel teaches at UCLA.

Lawrence Grobel has written for many publications and has interviewed everyone from Truman Capote, Marlon Brando and Barbra Streisand to Halle Berry and Drew Barrymore. The author of The Art of the Interview, Grobel teaches at UCLA.

Extras

Chapter One"You Have MS."

I'm in the intensive care unit of Beth Israel North waiting to go into surgery, where I have a 50 percent chance of dying. The blood vessel leading to my sinuses is ten times the size it should be and blood has been pouring out of my nose for nearly a month. There are tubes going in and out of me, connected to a heart monitor. The cauterization inside my nose suddenly bursts and blood starts shooting like a jet stream across the bed. I look at the heart monitor and see the numbers go from 65 to 58, to 50, 40, 29. My blood pressure is 80/10. The monitor starts making noises and just before it flatlines I shout for the doctor. I don't want to die, but the machine shows 0 as I pass out. I'm dead.

But somehow I'm aware of what's going on around me and I'm freaked out. There are four doctors trying to revive me. And one stranger, a strange sort of apparition cloaked in a shroud. Is it an angel? Am I going to be escorted to the white light? The figure approaches me and softly says, "Montel, Montel, you need to calm the fuck down."

The doctors aren't aware of this stranger. I don't know who he is-I'm not even sure it's a he-but he's not like any angel I ever imagined. Whoever it is, it makes me laugh.

"What are you talking about?" I say. I'm laughing because here is my big deathbed scene and I get an angel with a filthy mouth. I'm dying and he's telling me to stay calm?

"You heard me," he says again. "If I don't tell it to you this way you are not going to listen. So calm the fuck down. It's not your time. You've still got too many things to accomplish." One of the doctors, Dr. Swarup, grabs my chest with his fingers and twists my skin hard enough to leave a bruise. "Montel!" he shouts. "Wake up! Wake up!"

Another doctor starts yelling as well. "Who are you talking to? You've got to calm down!"

"That's what he just said," I murmur and point to the apparition.

When I finally calm down, I look up and it's gone. My four doctors bring me back.

The next morning the anesthesiologist comes to prepare me for surgery. I say to her, "Make sure I wake up from this." I want to live. I'm not sure if what happened the day before is something that I imagined to ease my concern about dying or if it was truly a visitation, but I feel a sense of calm that I haven't felt for a very long time.

It isn't going to last.

Ten months later, in February of 1999, I flew to Salt Lake City, Utah, to appear in an episode of the TV show Touched by an Angel. On the plane, I got up to use the bathroom, and when I returned I stumbled and fell into the seat next to Grace, my wife. Our relationship was not at a high point and now what the hell was this? A searing pain had swept through my legs from the knees to the feet as if they had been scalded by a blowtorch. It wasn't a momentary fire but a continuous one. My feet felt like someone had taken a sharp, pointed branding iron and stuck it not just between my toes but through them. The pain was so excruciating I didn't think I would be able to walk, let alone act. But I also knew that I had made a commitment to do the show and I felt obligated to honor that commitment.

I work out with a trainer every morning, and a day earlier I had trained with somebody new doing a different type of leg workout. I thought that I must have done something horribly wrong in my workout. Every hour for the next two days, my legs and feet hurt more. We were staying with a very close friend of mine, Dr. Andy Hines, who is a plastic surgeon. I told him about the pain and that I thought I might have really screwed up my back. By then my feet had gone numb, as had a small spot on my side from my hip to the bottom of my rib cage. I also felt pain in my stomach that was taking my breath away. Andy told Grace he suspected I had a neurological disorder but he didn't say anything to me because he knew I had to work the next day.

I didn't want to tell anybody that I was hurting the first day on the set because then they'd have to cancel the shoot, and that would probably be the last guest-starring appearance I'd ever get. So I took six Tylenol, sucked it up and went to work. When anyone asked what was wrong, I said I pinched a nerve in my back from working out and it would be no problem.

It should have been a fun shoot. It was a beautiful day. The air was clear, the sun was shining. My love interest was Cynthia Nixon, who had just signed a deal for Sex and the City. I was playing a juicy role, a cult leader who was destined to go straight to hell. We had two tough scenes that day. One was the opening, in which I was recruiting people to come with me to my compound. I had to walk up and down the aisles in front of twenty or thirty people giving a long speech. If you ever see this episode, don't be fooled; what may appear to be intense Acting with a capital A is actually physical pain. Every step I took was so painful I had to clasp my hands in front of me and squeeze as hard as I could to deflect how much my feet hurt.

I got back to Andy's around five p.m. and collapsed. I had the next day off, which was a relief because I woke up in even worse pain. "I really want you to go see a friend of mine," Andy said. "He's a neurologist and he may be able to explain some of this." Then he casually asked if anyone had ever mentioned multiple sclerosis to me.

"Yeah," I said, "but I know it's not that. Twenty years ago I had a doctor in the marines suggest I should be tested for MS. Turned out it disappeared. Six years ago, same thing: this doctor in Las Vegas put me through an MRI [magnetic resonance imager], thought it was MS, sent me to an eye clinic in Philadelphia. The top doctor there looked at the MRI and said those people were crazy: it wasn't MS-it was an inner-ear infection I had caught from swimming in the bay. Once these doctors see the kind of shape I'm in and understand the kind of power weight lifting I do, they know I'm no victim of disease. I just get these damn pains and need something to stop them."

I looked at Andy and saw he wasn't buying it. And that kind of took me aback, because I am where I am today because of my self-assurance, the power of my conviction; it's the power of who I am. If Albert Einstein were alive today and came on my show, I probably could argue him out of being so sure that e equals mc squared.

But there was no talking my way out of the pain I was feeling, so Andy's sister-in-law Wendy drove me to the neurologist in Salt Lake City. She had to drive because I was hurting so bad I could not put my foot on the gas pedal.

The doctor's office was in one of those executive centers that look like a strip mall. I was expecting him to give me some pain medication and send me on my way. I wasn't expecting him to turn my life upside down.

He said that from what Andy had told him and seeing me walk, he knew exactly what was wrong, but he didn't say what it was and I didn't ask. He did a quick eye exam, holding up fingers for me to count; told me to bend over; and had me remove my pants so he could conduct some needle tests to check my legs.

I told him I had been on some medication for the past few months because I had been urinating a lot. I also said that I was having trouble releasing my bowels-I would try to go six times in a row but nothing happened. He just nodded. These were classic symptoms of the disease I didn't yet know I had.

He began sticking needles into my feet.

"What do you feel?"

"Nothing."

He poked me in the legs, drawing blood. "Do you feel this?"

"No."

He poked some more. I didn't feel anything.

For the first time I began to face how seriously numb I had gone in various places on my body. Two years before this I had burned myself on the space heater in my office, a second-degree burn, and I didn't even know it. I'd had a car back over my foot and didn't realize it until a half hour later when my foot started hurting.

The doctor then checked my cremasteric reflex, which is supposed to make the genitals move when the thigh is touched in a certain spot. Mine didn't. "I can tell you without doing any further tests that you have MS," he said. Just like that. Very matter-of-fact.

What the hell was he talking about, MS? Even though I'd heard those two letters before, I barely knew what MS was. I thought it was the disease Jerry Lewis was always raising money to defeat. Kids in wheelchairs. I was an adult. I couldn't have that. I didn't know anything about MS. I thought it was muscular dystrophy.

He asked if I knew any other neurologists I trusted. Now I was back on more solid ground. "Sure, I have a doctor at Harvard, Dr. Allen Counter, who could help set up appointments with a neurologist there." He had invited me up to Harvard to speak on African-Americans and minorities in the media two months earlier, and had impressed me as one of the true treasures of this country. He was a neurophysiologist at Harvard Medical School who had been the director of the Harvard Foundation for more than two decades. I was dropping Dr. Counter's name as if to let this doctor know I knew real doctors who could counter his cocksure diagnosis.

"Then you ought to go to Harvard," he said, "because you have MS-there's no question."

I gave him a look of infinite hatred ... and broke down. Tears have always come easily for me, but this time I was crying at the thought of my own funeral. My kids were going to be robbed of their dad. My hopes of fulfilling the old high school yearbook prediction of one day residing at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue were instantly crushed. This black man wasn't going to be the first African-American president. He was just going to be one dead talk show host. My tears clearly made the doctor uncomfortable. "Don't cry," he said. "There's nothing you can do about it."

Thanks a lot, I thought, and I cried even more. I've had doctors look me in the face and just because I had convinced them that they should look somewhere else they changed their minds about their diagnosis. But I suspected this time the doctor might be right that I had a disease. And a disease meant that I wasn't going to ever be the same.

When I finally regained some semblance of composure I asked him, "Where do we go from here?"

"Truthfully?" he said. "You should not exercise because it puts an unnecessary strain on your body. It's not the best idea for you."

"But I'm a weight lifter," I said. "I work out every day."

"Your exercise routines will have to change," he said. "First, you must wait until this bout has gone. Then, see your doctor at Harvard."

I tried to protest that his diagnosis might be wrong. Doctors today often second-guess themselves because they don't want to get sued. And with a disease like MS, where the symptoms can come and go, being in remission could potentially validate that I was misdiagnosed. But he wouldn't back down, saying, again, in that painfully matter-of-fact way: "Go ahead and see your Harvard doctor, and he will confirm what I've just told you. You have MS. You will have to learn how to live with it."

I didn't like the cocky manner this doctor had. I didn't like the blunt way he diagnosed me. But most of all I didn't like him because he was the messenger, and what he was telling me was that my life was about to change. He was suggesting I go from being a strong healthy man to a weak, ill patient. He was telling me, without saying it, that I had better prepare myself to become a cripple. That my days of bodybuilding would become months and years of body breakdown. He poked and stabbed my numb lower body and showed me that what was in store for me was either excruciating pain or no feeling whatsoever. He was pronouncing my death sentence. I was forty-three years old and he was telling me that I was going to die.

I didn't want him to tell anybody. I made sure we were clear about doctor-patient privilege before I went out to the car, where Wendy was waiting. Immediately I called Dr. Counter on my cell phone and left a message saying I needed some help. Wendy asked if I was okay.

"Yeah, yeah-everything's okay."

When we got back to Andy's house I pulled Andy and his wife, Kim, aside and said, "You can't say anything to anybody; our entire friendship really hinges on this. If this gets out I'll know it's you." We all got emotional. They hugged me and told me over and over, "It's not the end of the world," while I let loose all my fears.

"What am I going to do? I don't want my kids to know. I don't want anyone to know. I'll lose my job. I'll never get asked to act again. I'm going to die." We started pulling out books, reading anything in the house we could find about MS. I learned that there were four different stages: benign, regressive, relapsing-remitting, and progressive. I assumed I must be progressive, the worst category, because I wasn't bad the week before, and the pain in my legs was just getting worse.

At the same time, as much as I was thinking the worst, I was trying my best to act normal-I still had to finish the episode of Touched by an Angel. I finally got Dr. Counter on the phone and he suggested that we immediately set up an appointment with two of Harvard's top MS doctors, Dr. Howard Weiner and Dr. Michael Olek, and in the interim, get some Vicodin pain pills. I took five in an hour and they barely helped, other than putting my brain in a whole other place.

All day Wednesday I was cloudy and had a little bit of a problem remembering my lines, but I tried my best to hide my pain and numbness. I kept up the charade that I had a back problem and everyone accepted it. I was feeling so bad and so weak that I decided not to listen to the doctor and went to the gym before shooting the last two days. I used every ounce of strength to do it, but I worked out. When we shot the climactic scene in which the angel and I do battle and I get set on fire, the script called for me to cry. It was the easiest acting I've ever had to do. I just let go on the set; I cried for a day and a half. Everyone was saying what a great actor I was and I let them-thanks, yes, I appreciate that-but those tears weren't fake-I was grieving for my life. As soon as the episode wrapped Grace and I flew to Boston, where Dr. Counter set me up with Dr. Michael Olek. I kept saying to Grace about the Salt Lake City doctor, "Well, maybe this guy's wrong."

Dr. Olek was about five feet eight inches and looked like he was thirteen years old. But he had an impressive number of diplomas hanging on the wall behind his desk. He gave me a thorough clinical examination as I ranted and raved about how much of a jerk the other doctor was and generally made it clear he better not treat me that way. He checked my hands, eyes, ears, face, tongue and throat. He listened to my speech. He checked each leg from heel to shin. He used a pin, and a tuning fork. He checked my motor skills. Then he put me through the MRI, a multimillion-dollar scanner that uses magnetic fields up to 30,000 times stronger than the earth's radio-wave pulses to produce pictures of the central nervous system-far more specific than those produced by CAT scanners or X-rays.

Continues...

I'm in the intensive care unit of Beth Israel North waiting to go into surgery, where I have a 50 percent chance of dying. The blood vessel leading to my sinuses is ten times the size it should be and blood has been pouring out of my nose for nearly a month. There are tubes going in and out of me, connected to a heart monitor. The cauterization inside my nose suddenly bursts and blood starts shooting like a jet stream across the bed. I look at the heart monitor and see the numbers go from 65 to 58, to 50, 40, 29. My blood pressure is 80/10. The monitor starts making noises and just before it flatlines I shout for the doctor. I don't want to die, but the machine shows 0 as I pass out. I'm dead.

But somehow I'm aware of what's going on around me and I'm freaked out. There are four doctors trying to revive me. And one stranger, a strange sort of apparition cloaked in a shroud. Is it an angel? Am I going to be escorted to the white light? The figure approaches me and softly says, "Montel, Montel, you need to calm the fuck down."

The doctors aren't aware of this stranger. I don't know who he is-I'm not even sure it's a he-but he's not like any angel I ever imagined. Whoever it is, it makes me laugh.

"What are you talking about?" I say. I'm laughing because here is my big deathbed scene and I get an angel with a filthy mouth. I'm dying and he's telling me to stay calm?

"You heard me," he says again. "If I don't tell it to you this way you are not going to listen. So calm the fuck down. It's not your time. You've still got too many things to accomplish." One of the doctors, Dr. Swarup, grabs my chest with his fingers and twists my skin hard enough to leave a bruise. "Montel!" he shouts. "Wake up! Wake up!"

Another doctor starts yelling as well. "Who are you talking to? You've got to calm down!"

"That's what he just said," I murmur and point to the apparition.

When I finally calm down, I look up and it's gone. My four doctors bring me back.

The next morning the anesthesiologist comes to prepare me for surgery. I say to her, "Make sure I wake up from this." I want to live. I'm not sure if what happened the day before is something that I imagined to ease my concern about dying or if it was truly a visitation, but I feel a sense of calm that I haven't felt for a very long time.

It isn't going to last.

Ten months later, in February of 1999, I flew to Salt Lake City, Utah, to appear in an episode of the TV show Touched by an Angel. On the plane, I got up to use the bathroom, and when I returned I stumbled and fell into the seat next to Grace, my wife. Our relationship was not at a high point and now what the hell was this? A searing pain had swept through my legs from the knees to the feet as if they had been scalded by a blowtorch. It wasn't a momentary fire but a continuous one. My feet felt like someone had taken a sharp, pointed branding iron and stuck it not just between my toes but through them. The pain was so excruciating I didn't think I would be able to walk, let alone act. But I also knew that I had made a commitment to do the show and I felt obligated to honor that commitment.

I work out with a trainer every morning, and a day earlier I had trained with somebody new doing a different type of leg workout. I thought that I must have done something horribly wrong in my workout. Every hour for the next two days, my legs and feet hurt more. We were staying with a very close friend of mine, Dr. Andy Hines, who is a plastic surgeon. I told him about the pain and that I thought I might have really screwed up my back. By then my feet had gone numb, as had a small spot on my side from my hip to the bottom of my rib cage. I also felt pain in my stomach that was taking my breath away. Andy told Grace he suspected I had a neurological disorder but he didn't say anything to me because he knew I had to work the next day.

I didn't want to tell anybody that I was hurting the first day on the set because then they'd have to cancel the shoot, and that would probably be the last guest-starring appearance I'd ever get. So I took six Tylenol, sucked it up and went to work. When anyone asked what was wrong, I said I pinched a nerve in my back from working out and it would be no problem.

It should have been a fun shoot. It was a beautiful day. The air was clear, the sun was shining. My love interest was Cynthia Nixon, who had just signed a deal for Sex and the City. I was playing a juicy role, a cult leader who was destined to go straight to hell. We had two tough scenes that day. One was the opening, in which I was recruiting people to come with me to my compound. I had to walk up and down the aisles in front of twenty or thirty people giving a long speech. If you ever see this episode, don't be fooled; what may appear to be intense Acting with a capital A is actually physical pain. Every step I took was so painful I had to clasp my hands in front of me and squeeze as hard as I could to deflect how much my feet hurt.

I got back to Andy's around five p.m. and collapsed. I had the next day off, which was a relief because I woke up in even worse pain. "I really want you to go see a friend of mine," Andy said. "He's a neurologist and he may be able to explain some of this." Then he casually asked if anyone had ever mentioned multiple sclerosis to me.

"Yeah," I said, "but I know it's not that. Twenty years ago I had a doctor in the marines suggest I should be tested for MS. Turned out it disappeared. Six years ago, same thing: this doctor in Las Vegas put me through an MRI [magnetic resonance imager], thought it was MS, sent me to an eye clinic in Philadelphia. The top doctor there looked at the MRI and said those people were crazy: it wasn't MS-it was an inner-ear infection I had caught from swimming in the bay. Once these doctors see the kind of shape I'm in and understand the kind of power weight lifting I do, they know I'm no victim of disease. I just get these damn pains and need something to stop them."

I looked at Andy and saw he wasn't buying it. And that kind of took me aback, because I am where I am today because of my self-assurance, the power of my conviction; it's the power of who I am. If Albert Einstein were alive today and came on my show, I probably could argue him out of being so sure that e equals mc squared.

But there was no talking my way out of the pain I was feeling, so Andy's sister-in-law Wendy drove me to the neurologist in Salt Lake City. She had to drive because I was hurting so bad I could not put my foot on the gas pedal.

The doctor's office was in one of those executive centers that look like a strip mall. I was expecting him to give me some pain medication and send me on my way. I wasn't expecting him to turn my life upside down.

He said that from what Andy had told him and seeing me walk, he knew exactly what was wrong, but he didn't say what it was and I didn't ask. He did a quick eye exam, holding up fingers for me to count; told me to bend over; and had me remove my pants so he could conduct some needle tests to check my legs.

I told him I had been on some medication for the past few months because I had been urinating a lot. I also said that I was having trouble releasing my bowels-I would try to go six times in a row but nothing happened. He just nodded. These were classic symptoms of the disease I didn't yet know I had.

He began sticking needles into my feet.

"What do you feel?"

"Nothing."

He poked me in the legs, drawing blood. "Do you feel this?"

"No."

He poked some more. I didn't feel anything.

For the first time I began to face how seriously numb I had gone in various places on my body. Two years before this I had burned myself on the space heater in my office, a second-degree burn, and I didn't even know it. I'd had a car back over my foot and didn't realize it until a half hour later when my foot started hurting.

The doctor then checked my cremasteric reflex, which is supposed to make the genitals move when the thigh is touched in a certain spot. Mine didn't. "I can tell you without doing any further tests that you have MS," he said. Just like that. Very matter-of-fact.

What the hell was he talking about, MS? Even though I'd heard those two letters before, I barely knew what MS was. I thought it was the disease Jerry Lewis was always raising money to defeat. Kids in wheelchairs. I was an adult. I couldn't have that. I didn't know anything about MS. I thought it was muscular dystrophy.

He asked if I knew any other neurologists I trusted. Now I was back on more solid ground. "Sure, I have a doctor at Harvard, Dr. Allen Counter, who could help set up appointments with a neurologist there." He had invited me up to Harvard to speak on African-Americans and minorities in the media two months earlier, and had impressed me as one of the true treasures of this country. He was a neurophysiologist at Harvard Medical School who had been the director of the Harvard Foundation for more than two decades. I was dropping Dr. Counter's name as if to let this doctor know I knew real doctors who could counter his cocksure diagnosis.

"Then you ought to go to Harvard," he said, "because you have MS-there's no question."

I gave him a look of infinite hatred ... and broke down. Tears have always come easily for me, but this time I was crying at the thought of my own funeral. My kids were going to be robbed of their dad. My hopes of fulfilling the old high school yearbook prediction of one day residing at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue were instantly crushed. This black man wasn't going to be the first African-American president. He was just going to be one dead talk show host. My tears clearly made the doctor uncomfortable. "Don't cry," he said. "There's nothing you can do about it."

Thanks a lot, I thought, and I cried even more. I've had doctors look me in the face and just because I had convinced them that they should look somewhere else they changed their minds about their diagnosis. But I suspected this time the doctor might be right that I had a disease. And a disease meant that I wasn't going to ever be the same.

When I finally regained some semblance of composure I asked him, "Where do we go from here?"

"Truthfully?" he said. "You should not exercise because it puts an unnecessary strain on your body. It's not the best idea for you."

"But I'm a weight lifter," I said. "I work out every day."

"Your exercise routines will have to change," he said. "First, you must wait until this bout has gone. Then, see your doctor at Harvard."

I tried to protest that his diagnosis might be wrong. Doctors today often second-guess themselves because they don't want to get sued. And with a disease like MS, where the symptoms can come and go, being in remission could potentially validate that I was misdiagnosed. But he wouldn't back down, saying, again, in that painfully matter-of-fact way: "Go ahead and see your Harvard doctor, and he will confirm what I've just told you. You have MS. You will have to learn how to live with it."

I didn't like the cocky manner this doctor had. I didn't like the blunt way he diagnosed me. But most of all I didn't like him because he was the messenger, and what he was telling me was that my life was about to change. He was suggesting I go from being a strong healthy man to a weak, ill patient. He was telling me, without saying it, that I had better prepare myself to become a cripple. That my days of bodybuilding would become months and years of body breakdown. He poked and stabbed my numb lower body and showed me that what was in store for me was either excruciating pain or no feeling whatsoever. He was pronouncing my death sentence. I was forty-three years old and he was telling me that I was going to die.

I didn't want him to tell anybody. I made sure we were clear about doctor-patient privilege before I went out to the car, where Wendy was waiting. Immediately I called Dr. Counter on my cell phone and left a message saying I needed some help. Wendy asked if I was okay.

"Yeah, yeah-everything's okay."

When we got back to Andy's house I pulled Andy and his wife, Kim, aside and said, "You can't say anything to anybody; our entire friendship really hinges on this. If this gets out I'll know it's you." We all got emotional. They hugged me and told me over and over, "It's not the end of the world," while I let loose all my fears.

"What am I going to do? I don't want my kids to know. I don't want anyone to know. I'll lose my job. I'll never get asked to act again. I'm going to die." We started pulling out books, reading anything in the house we could find about MS. I learned that there were four different stages: benign, regressive, relapsing-remitting, and progressive. I assumed I must be progressive, the worst category, because I wasn't bad the week before, and the pain in my legs was just getting worse.

At the same time, as much as I was thinking the worst, I was trying my best to act normal-I still had to finish the episode of Touched by an Angel. I finally got Dr. Counter on the phone and he suggested that we immediately set up an appointment with two of Harvard's top MS doctors, Dr. Howard Weiner and Dr. Michael Olek, and in the interim, get some Vicodin pain pills. I took five in an hour and they barely helped, other than putting my brain in a whole other place.

All day Wednesday I was cloudy and had a little bit of a problem remembering my lines, but I tried my best to hide my pain and numbness. I kept up the charade that I had a back problem and everyone accepted it. I was feeling so bad and so weak that I decided not to listen to the doctor and went to the gym before shooting the last two days. I used every ounce of strength to do it, but I worked out. When we shot the climactic scene in which the angel and I do battle and I get set on fire, the script called for me to cry. It was the easiest acting I've ever had to do. I just let go on the set; I cried for a day and a half. Everyone was saying what a great actor I was and I let them-thanks, yes, I appreciate that-but those tears weren't fake-I was grieving for my life. As soon as the episode wrapped Grace and I flew to Boston, where Dr. Counter set me up with Dr. Michael Olek. I kept saying to Grace about the Salt Lake City doctor, "Well, maybe this guy's wrong."

Dr. Olek was about five feet eight inches and looked like he was thirteen years old. But he had an impressive number of diplomas hanging on the wall behind his desk. He gave me a thorough clinical examination as I ranted and raved about how much of a jerk the other doctor was and generally made it clear he better not treat me that way. He checked my hands, eyes, ears, face, tongue and throat. He listened to my speech. He checked each leg from heel to shin. He used a pin, and a tuning fork. He checked my motor skills. Then he put me through the MRI, a multimillion-dollar scanner that uses magnetic fields up to 30,000 times stronger than the earth's radio-wave pulses to produce pictures of the central nervous system-far more specific than those produced by CAT scanners or X-rays.

Continues...

Descriere

In this intimate and inspiring memoir, the Emmy( Award-winning talk show host reveals how his shocking 1999 diagnosis of multiple sclerosis changed his life, how to inform friends and family, understanding and living with MS, physical and mental exercises, and more.