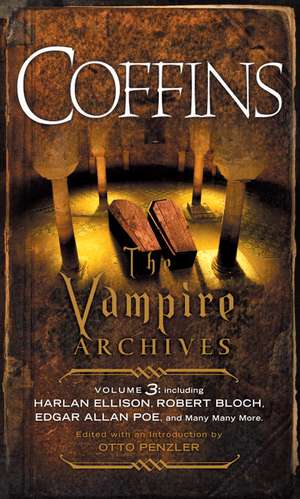

Coffins: The Vampire Archives, Volume 3

Editat de Otto Penzleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2010

Coffins, the third volume in the mass market series, contains some of the best of the best of vampire fiction. Including Harlan Ellison, Robert Bloch, Edgar Allan Poe, and F. Paul Wilson, it takes its readers deep inside the crypts of the living dead, in all their supernatural splendor.

Featuring:

· Heart Pounding Shrieks

· Blood Soaked Moonlit Hunts

· High Stakes Adventure

· Evil Assignations

Preț: 49.04 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 74

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.39€ • 9.70$ • 7.81£

9.39€ • 9.70$ • 7.81£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307742230

ISBN-10: 0307742237

Pagini: 502

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307742237

Pagini: 502

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Otto Penzler is the proprietor of The Mysterious Bookshop in New York City. He was publisher of The Armchair Detective, the founder of the Mysterious Press and the Armchair Detective Library, and created the publishing firm Otto Penzler Books. He is a recipient of an Edgar Award for The Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection and the Ellery Queen Award by the Mystery Writers of America for his many contributions to the field. He is the editor of The Vampire Archives and The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, which was a New York Times bestseller. He is also the series editor of The Best American Mystery Stories of the Year. His other anthologies include Murder for Love, Murder for Revenge, Murder and Obsession, The 50 Greatest Mysteries of All Time, and The Best American Mystery Stories of the Century. He wrote 101 Greatest Movies of Mystery & Suspense. He lives in New York City.

Extras

The Living Dead

...

Robert Bloch

All day long he rested, while the guns thundered in the village below. Then, in the slanting shadows of the late afternoon, the rumbling echoes faded into the distance and he knew it was over. The American advance had crossed the river. They were gone at last, and it was safe once more.

Above the village, in the crumbling ruins of the great château atop the wooded hillside, Count Barsac emerged from the crypt.

The Count was tall and thin—cadaverously thin, in a manner most hideously appropriate. His face and hands had a waxen pallor; his hair was dark, but not as dark as his eyes and the hollows beneath them. His cloak was black, and the sole touch of color about his person was the vivid redness of his lips when they curled in a smile.

He was smiling now, in the twilight, for it was time to play the game.

The name of the game was Death, and the Count had played it many times.

He had played it in Paris on the stage of the Grand Guignol; his name had been plain Eric Karon then, but still he’d won a certain renown for his interpretation of bizarre roles. Then the war had come and, with it, his opportunity.

Long before the Germans took Paris, he’d joined their Underground, working long and well. As an actor he’d been invaluable.

And this, of course, was his ultimate reward—to play the supreme role, not on the stage, but in real life. To play without the artifice of spotlights, in true darkness; this was the actor’s dream come true. He had even helped to fashion the plot.

“Simplicity itself,” he told his German superiors. “Château Barsac has been deserted since the Revolution. None of the peasants from the village dare to venture near it, even in daylight, because of the legend. It is said, you see, that the last Count Barsac was a vampire.”

And so it was arranged. The shortwave transmitter had been set up in the large crypt beneath the château, with three skilled operators in attendance, working in shifts. And he, “Count Barsac,” in charge of the entire operation, as guardian angel. Rather, as guardian demon.

“There is a graveyard on the hillside below,” he informed them. “A humble resting place for poor and ignorant people. It contains a single imposing crypt—the ancestral tomb of the Barsacs. We shall open that crypt, remove the remains of the last Count, and allow the villagers to discover that the coffin is empty. They will never dare come near the spot or the château again, because this will prove that the legend is true—Count Barsac is a vampire, and walks once more.”

The question came then. “What if there are sceptics? What if someone does not believe?”

And he had his answer ready. “They will believe. For at night I shall walk—I, Count Barsac.”

After they saw him in the makeup, wearing the black cloak, there were no more questions. The role was his.

The role was his, and he’d played it well. The Count nodded to himself as he climbed the stairs and entered the roofless foyer of the château, where only a configuration of cobwebs veiled the radiance of the rising moon.

Now, of course, the curtain must come down. If the American advance had swept past the village below, it was time to make one’s bow and exit. And that too had been well arranged.

During the German withdrawal another advantageous use had been made of the tomb in the graveyard. A cache of Air Marshal Goering’s art treasures now rested safely and undisturbed within the crypt. A truck had been placed in the château. Even now the three wireless operators would be playing new parts—driving the truck down the hillside to the tomb, placing the objets d’art in it.

By the time the Count arrived there, everything would be packed. They would then don the stolen American Army uniforms, carry the forged identifications and permits, drive through the lines across the river, and rejoin the German forces at a predesignated spot. Nothing had been left to chance. Someday, when he wrote his memoirs . . .

But there was not time to consider that now. The Count glanced up through the gaping aperture in the ruined roof. The moon was high. It was time to leave.

In a way he hated to go. Where others saw only dust and cobwebs he saw a stage—the setting of his finest performance. Playing a vampire’s role had not addicted him to the taste of blood—but as an actor he enjoyed the taste of triumph. And he had triumphed here.

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.” Shakespeare’s line. Shakespeare, who had written of ghosts and witches, of bloody apparitions. Because Shakespeare knew that his audiences, the stupid masses, believed in such things—just as they still believed today. A great actor could always make them believe.

The Count moved into the shadowy darkness outside the entrance of the château. He started down the pathway toward the beckoning trees.

It was here, amid the trees, that he had come upon Raymond, one evening weeks ago. Raymond had been his most appreciative audience—a stern, dignified, white-haired elderly man, mayor of the village of Barsac. But there had been nothing dignified about the old fool when he’d caught sight of the Count looming up before him out of the night. He’d screamed like a woman and run.

Probably Raymond had been prowling around, intent on poaching, but all that had been forgotten after his encounter in the woods. The mayor was the one to thank for spreading the rumors that the Count was again abroad. He and Clodez, the oafish miller, had then led an armed band to the graveyard and entered the Barsac tomb. What a fright they got when they discovered the Count’s coffin open and empty!

The coffin had contained only dust that had been scattered to the winds, but they could not know that. Nor could they know about what had happened to Suzanne.

The Count was passing the banks of a small stream now. Here, on another evening, he’d found the girl—Raymond’s daughter, as luck would have it—in an embrace with young Antoine LeFevre, her lover. Antoine’s shattered leg had invalided him out of the army, but he ran like a deer when he glimpsed the cloaked and grinning Count. Suzanne had been left behind and that was unfortunate, because it was necessary to dispose of her. Her body had been buried in the woods, beneath great stones, and there was no question of discovery; still, it was a regrettable incident.

In the end, however, everything was for the best. Now silly superstitious Raymond was doubly convinced that the vampire walked. He had seen the creature himself, had seen the empty tomb and the open coffin; his own daughter had disappeared. At his command none dared venture near the graveyard, the woods, or the château beyond.

Poor Raymond! He was not even a mayor any more—his village had been destroyed in the bombardment. Just an ignorant, broken old man, mumbling his idiotic nonsense about the “living dead.”

The Count smiled and walked on, his cloak fluttering in the breeze, casting a batlike shadow on the pathway before him. He could see the graveyard now, the tilted tombstones rising from the earth like leprous fingers rotting in the moonlight. His smile faded; he did not like such thoughts. Perhaps the greatest tribute to his talent as an actor lay in his actual aversion to death, to darkness and what lurked in the night. He hated the sight of blood, had developed within himself an almost claustrophobic dread of the confinement of the crypt.

Yes, it had been a great role, but he was thankful it was ending. It would be good to play the man once more, and cast off the creature he had created.

As he approached the crypt he saw the truck waiting in the shadows. The entrance to the tomb was open, but no sounds issued from it. That meant his colleagues had completed their task of loading and were ready to go. All that remained now was to change his clothing, remove the makeup, and depart.

The Count moved to the darkened truck. And then . . .

Then they were upon him, and he felt the tines of the pitchfork bite into his back, and as the flash of lanterns dazzled his eyes he heard the stern command. “Don’t move!”

He didn’t move. He could only stare as they surrounded him—Antoine, Clodez, Raymond, and the others, a dozen peasants from the village. A dozen armed peasants, glaring at him in mingled rage and fear, holding him at bay.

But how could they dare?

...

Robert Bloch

All day long he rested, while the guns thundered in the village below. Then, in the slanting shadows of the late afternoon, the rumbling echoes faded into the distance and he knew it was over. The American advance had crossed the river. They were gone at last, and it was safe once more.

Above the village, in the crumbling ruins of the great château atop the wooded hillside, Count Barsac emerged from the crypt.

The Count was tall and thin—cadaverously thin, in a manner most hideously appropriate. His face and hands had a waxen pallor; his hair was dark, but not as dark as his eyes and the hollows beneath them. His cloak was black, and the sole touch of color about his person was the vivid redness of his lips when they curled in a smile.

He was smiling now, in the twilight, for it was time to play the game.

The name of the game was Death, and the Count had played it many times.

He had played it in Paris on the stage of the Grand Guignol; his name had been plain Eric Karon then, but still he’d won a certain renown for his interpretation of bizarre roles. Then the war had come and, with it, his opportunity.

Long before the Germans took Paris, he’d joined their Underground, working long and well. As an actor he’d been invaluable.

And this, of course, was his ultimate reward—to play the supreme role, not on the stage, but in real life. To play without the artifice of spotlights, in true darkness; this was the actor’s dream come true. He had even helped to fashion the plot.

“Simplicity itself,” he told his German superiors. “Château Barsac has been deserted since the Revolution. None of the peasants from the village dare to venture near it, even in daylight, because of the legend. It is said, you see, that the last Count Barsac was a vampire.”

And so it was arranged. The shortwave transmitter had been set up in the large crypt beneath the château, with three skilled operators in attendance, working in shifts. And he, “Count Barsac,” in charge of the entire operation, as guardian angel. Rather, as guardian demon.

“There is a graveyard on the hillside below,” he informed them. “A humble resting place for poor and ignorant people. It contains a single imposing crypt—the ancestral tomb of the Barsacs. We shall open that crypt, remove the remains of the last Count, and allow the villagers to discover that the coffin is empty. They will never dare come near the spot or the château again, because this will prove that the legend is true—Count Barsac is a vampire, and walks once more.”

The question came then. “What if there are sceptics? What if someone does not believe?”

And he had his answer ready. “They will believe. For at night I shall walk—I, Count Barsac.”

After they saw him in the makeup, wearing the black cloak, there were no more questions. The role was his.

The role was his, and he’d played it well. The Count nodded to himself as he climbed the stairs and entered the roofless foyer of the château, where only a configuration of cobwebs veiled the radiance of the rising moon.

Now, of course, the curtain must come down. If the American advance had swept past the village below, it was time to make one’s bow and exit. And that too had been well arranged.

During the German withdrawal another advantageous use had been made of the tomb in the graveyard. A cache of Air Marshal Goering’s art treasures now rested safely and undisturbed within the crypt. A truck had been placed in the château. Even now the three wireless operators would be playing new parts—driving the truck down the hillside to the tomb, placing the objets d’art in it.

By the time the Count arrived there, everything would be packed. They would then don the stolen American Army uniforms, carry the forged identifications and permits, drive through the lines across the river, and rejoin the German forces at a predesignated spot. Nothing had been left to chance. Someday, when he wrote his memoirs . . .

But there was not time to consider that now. The Count glanced up through the gaping aperture in the ruined roof. The moon was high. It was time to leave.

In a way he hated to go. Where others saw only dust and cobwebs he saw a stage—the setting of his finest performance. Playing a vampire’s role had not addicted him to the taste of blood—but as an actor he enjoyed the taste of triumph. And he had triumphed here.

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.” Shakespeare’s line. Shakespeare, who had written of ghosts and witches, of bloody apparitions. Because Shakespeare knew that his audiences, the stupid masses, believed in such things—just as they still believed today. A great actor could always make them believe.

The Count moved into the shadowy darkness outside the entrance of the château. He started down the pathway toward the beckoning trees.

It was here, amid the trees, that he had come upon Raymond, one evening weeks ago. Raymond had been his most appreciative audience—a stern, dignified, white-haired elderly man, mayor of the village of Barsac. But there had been nothing dignified about the old fool when he’d caught sight of the Count looming up before him out of the night. He’d screamed like a woman and run.

Probably Raymond had been prowling around, intent on poaching, but all that had been forgotten after his encounter in the woods. The mayor was the one to thank for spreading the rumors that the Count was again abroad. He and Clodez, the oafish miller, had then led an armed band to the graveyard and entered the Barsac tomb. What a fright they got when they discovered the Count’s coffin open and empty!

The coffin had contained only dust that had been scattered to the winds, but they could not know that. Nor could they know about what had happened to Suzanne.

The Count was passing the banks of a small stream now. Here, on another evening, he’d found the girl—Raymond’s daughter, as luck would have it—in an embrace with young Antoine LeFevre, her lover. Antoine’s shattered leg had invalided him out of the army, but he ran like a deer when he glimpsed the cloaked and grinning Count. Suzanne had been left behind and that was unfortunate, because it was necessary to dispose of her. Her body had been buried in the woods, beneath great stones, and there was no question of discovery; still, it was a regrettable incident.

In the end, however, everything was for the best. Now silly superstitious Raymond was doubly convinced that the vampire walked. He had seen the creature himself, had seen the empty tomb and the open coffin; his own daughter had disappeared. At his command none dared venture near the graveyard, the woods, or the château beyond.

Poor Raymond! He was not even a mayor any more—his village had been destroyed in the bombardment. Just an ignorant, broken old man, mumbling his idiotic nonsense about the “living dead.”

The Count smiled and walked on, his cloak fluttering in the breeze, casting a batlike shadow on the pathway before him. He could see the graveyard now, the tilted tombstones rising from the earth like leprous fingers rotting in the moonlight. His smile faded; he did not like such thoughts. Perhaps the greatest tribute to his talent as an actor lay in his actual aversion to death, to darkness and what lurked in the night. He hated the sight of blood, had developed within himself an almost claustrophobic dread of the confinement of the crypt.

Yes, it had been a great role, but he was thankful it was ending. It would be good to play the man once more, and cast off the creature he had created.

As he approached the crypt he saw the truck waiting in the shadows. The entrance to the tomb was open, but no sounds issued from it. That meant his colleagues had completed their task of loading and were ready to go. All that remained now was to change his clothing, remove the makeup, and depart.

The Count moved to the darkened truck. And then . . .

Then they were upon him, and he felt the tines of the pitchfork bite into his back, and as the flash of lanterns dazzled his eyes he heard the stern command. “Don’t move!”

He didn’t move. He could only stare as they surrounded him—Antoine, Clodez, Raymond, and the others, a dozen peasants from the village. A dozen armed peasants, glaring at him in mingled rage and fear, holding him at bay.

But how could they dare?

Recenzii

“Sink your teeth in.”—People

Descriere

This collection includes tales of the vampire by such notable authors as Robert Bloch, Harlan Ellison, Edgar Allan Poe, and Arthur Conan Doyle. Original.