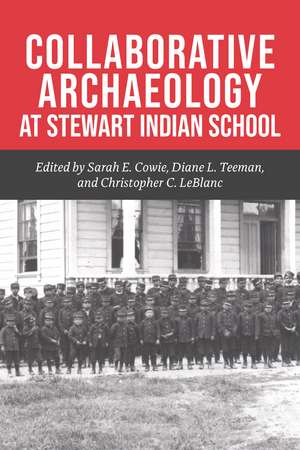

Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School

Autor Sarah E. Cowie, Diane L. Teeman, Christopher C. LeBlancen Limba Engleză Hardback – 10 sep 2019 – vârsta ani

Winner of the 2019 Mark E. Mack Community Engagement Award from the Society for Historical Archaeology, the collaborative archaeology project at the former Stewart Indian School documents the archaeology and history of a heritage project at a boarding school for American Indian children in the Western United States. In Collaborative Archaeology at Stewart Indian School, the team’s collective efforts shed light on the children’s education, foodways, entertainment, health, and resilience in the face of the U.S. government’s attempt to forcibly assimilate Native populations at the turn of the twentieth century, as well as school life in later years after reforms.

This edited volume addresses the theory, methods, and outcomes of collaborative archaeology conducted at the Stewart Indian School site and is a genuine collective effort between archaeologists, former students of the school, and other tribal members. With more than twenty contributing authors from the University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada Indian Commission, Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office, and members of Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone tribes, this rich case study is strongly influenced by previous work in collaborative and Indigenous archaeologies. It elaborates on those efforts by applying concepts of governmentality (legal instruments and practices that constrain and enable decisions, in this case, regarding the management of historical populations and modern heritage resources) as well as social capital (valued relations with others, in this case, between Native and non-Native stakeholders).

As told through the trials, errors, shared experiences, sobering memories, and stunning accomplishments of a group of students, archaeologists, and tribal members, this rare gem humanizes archaeological method and theory and bolsters collaborative archaeological research.

This edited volume addresses the theory, methods, and outcomes of collaborative archaeology conducted at the Stewart Indian School site and is a genuine collective effort between archaeologists, former students of the school, and other tribal members. With more than twenty contributing authors from the University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada Indian Commission, Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office, and members of Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone tribes, this rich case study is strongly influenced by previous work in collaborative and Indigenous archaeologies. It elaborates on those efforts by applying concepts of governmentality (legal instruments and practices that constrain and enable decisions, in this case, regarding the management of historical populations and modern heritage resources) as well as social capital (valued relations with others, in this case, between Native and non-Native stakeholders).

As told through the trials, errors, shared experiences, sobering memories, and stunning accomplishments of a group of students, archaeologists, and tribal members, this rare gem humanizes archaeological method and theory and bolsters collaborative archaeological research.

Preț: 426.73 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 640

Preț estimativ în valută:

81.66€ • 85.47$ • 67.96£

81.66€ • 85.47$ • 67.96£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781948908252

ISBN-10: 1948908255

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 35 b-w photos

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

ISBN-10: 1948908255

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 35 b-w photos

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Notă biografică

Sarah E. Cowie is an author and associate professor of anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Her research in archaeology has received recognitions from the Society for Historical Archaeology, the National Academy of Sciences, and the United States government.

Diane L. Teeman is a member of the Burns Paiute Tribe and Director of the Burns Paiute Tribe’s Culture & Heritage Department. She is currently a doctoral candidate at University of Nevada, Reno and has spent the past thirty years working toward tribal culture and heritage protection and revitalization.

Christopher C. LeBlanc is a heritage consultant at the University of Nevada, Reno and has over twenty years of experience in the fields of cultural and heritage resource management. He is currently working as a crew chief and archaeological technician in Reno, Nevada.

Diane L. Teeman is a member of the Burns Paiute Tribe and Director of the Burns Paiute Tribe’s Culture & Heritage Department. She is currently a doctoral candidate at University of Nevada, Reno and has spent the past thirty years working toward tribal culture and heritage protection and revitalization.

Christopher C. LeBlanc is a heritage consultant at the University of Nevada, Reno and has over twenty years of experience in the fields of cultural and heritage resource management. He is currently working as a crew chief and archaeological technician in Reno, Nevada.

Extras

A Multivocal Collaboration Story

The woman who initially reprimanded us began to weep as she told us her story. We were in the midst of a collaborative archaeological field school at the site of Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada, with a great deal of involvement from tribal members from multiple tribes, many of whom had members that passed through Stewart, as this alumna had, during its complicated ninety-year history as an off-reservation boarding school in Nevada. Like many other alumni and community members, she had heard about our widely advertised project and was visiting Stewart, as many alumni do on a semiregular basis, to reconnect with the place and the memories associated with it. She had been shouting at us from a distance as she passed by, saying that we didn’t know what we were getting into with excavating this place, that terrible things had happened here, and that we should leave such things alone. This is a common sentiment among many American Indians about archaeology in general, that things left by people in the past are too powerful to tamper with, especially things associated with negative experiences. Most people that talked to us about the project were either supportive or curious, but occasionally someone expressed concern. One tribe’s attorney contacted us, concerned that we might excavate graves of children who had died at the school, assuming that digging up graves was archaeologists’ primary occupation. On each of these interactions we had the opportunity to learn more about the school and what it meant to alumni, their families, and their tribes, as well as the history of the federal government’s attempt to forcibly assimilate Native Americans. We also had the opportunity to do better archaeology through public involvement, train students in a multivocal and collaborative approach to archaeological field methods, and demonstrate that archaeologists are not always grave robbers.

As this alumna was admonishing us, we might have ignored her, and continued our excavations as she passed by. But being a public archaeology project designed to learn from tribal members, instead we tentatively approached her and listened.

Her story was a complicated one, as many stories of this place are. There is so much sorrow and trauma here associated with the practices and repercussions of attempted assimilation. But she also wept as she described her childhood, in which her parents could not care for her, and how she wanted to attend Stewart to be a part of that community. She wept as she explained how important this place was to her; good and bad, it was her home. She said more people should know about Stewart Indian School’s significance, and agreed that our collaborative project might help raise awareness of Native peoples’ experiences there. She embraced some of us who listened to her story, and then she went on her way, walking to another part of campus with her memories.

Who could not be moved by such an experience? This interaction was typical on this project; it and many others humanized the experience of conducting archaeology here. It shows how place-based learning evokes knowledge and memories that are not so accessible elsewhere. It also exemplifies how valuing human relations can overcome seemingly conflicting worldviews, for example, between science and spirituality, or between federal heritage laws and a personal sense of what is right. Such discussions are critical to building relationships, and providing space for historically suppressed voices to tell their truths. Throughout this volume, our work is guided by a large body of literature on decolonizing methods and Indigenous archaeology, with inspiration from Native archaeologists working in their communities and guidance from foundational scholarship in Indigenous heritage studies (e.g., Atalay 2006, 2012; Colwell 2016; Deloria 1969; Dongoske et al. 2000; Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2006; Gould 2013; Gonzales et al. 2018; Laluk 2017; Martinez and Teeter 2015; Nicholas 2010; Schneider 2018; Silliman 2008; Smith 1999; Smith and Wobst 2005; Thomspon 2011; Teeman 2008; Two Bears 2010; Watkins 2000).

We combine many voices in this volume: Native and non-Native; elder and younger; academic, traditional, scientific, and personal. This created a manuscript that is multivocal and shifting in voice, with varied perspectives that may or may not mesh precisely with one another. We hope readers can appreciate the necessity of presenting different discourses in collaboration with each other and have patience with our approach. The result is that we are able to address a wide variety of topics and put them in conversation with each other.

Goals for the Stewart Indian School Project

Goals and objectives for the project were to study the interplay of tribal agency, social capital, and governmentalized archaeological discourse, and then outline a strategy for humanizing the process of respectful consultation among tribes, archaeologists, and the federal government. The project was funded by a three-year grant from the Army Research Office’s Young Investigator’s Program (Sarah Cowie, principle investigator) with the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR), in partnership with The Nevada Indian Commission, the Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) and numerous other Native and non-Native heritage specialists, volunteers, students, staff, and community members, many of whom are contributing authors to this volume.

Together we observed and researched areas where conflict arises, why there is still an impasse in conflicting discourses, and how governmentalization both helps and hinders processes of consultation. In chronicling this project’s archaeological practice and collaboration with tribal heritage specialists, this volume suggests some opportunities for building social capital and collaborating with tribes. From this work we found that it is possible to shift discourse around consultation to improve satisfaction of outcomes for all parties, at least in this particular case study.

This project involved a qualitative study of the impasse in federal/tribal discourses regarding heritage consultation. A network of partners collaboratively developed a model for improved consultation procedures. This volume, one of the results of the overall project, addresses the repercussions of federal government discourse surrounding Indigenous heritage and the utility of social capital for improving communication. The non-Native archaeologists who initiated the project organized a series of heritage discussions with tribal members who served as tribal consultants or partners in a collaborative, involved exchange of ideas. Tribal members participated as professional heritage specialists, staff, policy makers, and university academics, as well as undergraduate students that participated in the collaborative archaeological field school. In this case, fieldwork served as a foundation for discussing the improvement of tribal/federal heritage management issues. This strategy is informed by practice theory; phenomenology; and the linkages between place, memory, and multivocality that are valued by many tribal peoples (e.g., Basso 1996; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2006; Cowie et al. 2009), as well as recent pedagogical shifts in teaching collaborative archaeology (e.g., Silliman 2008).

Personnel working on this project worked collaboratively as equal contributors, rather than as subjects in data gathering. Each participant contributed his/her own knowledge about the topic. The UNR Office of Human Research Protection determined that this project did not constitute research on human subjects and was therefore exempt from human subjects review.

The proposed model for this project hinged on the idea that tribal/federal relationships could be improved by establishing relationships before the consultation process formally began; networks would then already be in place before potentially contentious issues arose. Federal agencies would make a minimal investment through heritage outreach activities first, not waiting until there is a problem to consult with tribes. The goal is for open dialog to continue productively when contentious heritage issues eventually arise.

Outreach activities during this project included collaborative work with several tribes and tribal heritage staff in Nevada and Oregon to deconstruct the current consultation process and to assess the ramifications of federally governmentalized discourse. In addition, this study models a heritage project that integrates both federal and Native discourses, in the form of a good faith offer of services to tribes for the mutual, long-term benefit of federal agencies as well as tribes. Services might include facilitating tribal visits to their traditional homelands on federally managed lands, and offering archaeological training and services to tribal entities. This project included funding for tribal undergraduate students to participate in the archaeological field school, and a number of Native consultants were hired for their expertise on various portions of the project. Other tribal members who work in heritage careers also participated in fieldwork as well, creating a productive exchange of ideas for Native and non-Native peoples and building social capital.

This three-year project began in the summer of 2012. Project participants reviewed the large body of literature regarding heritage consultation in both federal and Indigenous discourses. The literature was analyzed within the context of governmentality and agency theories. In the second year of the project personnel networked with tribal heritage specialists who were interested in participating and began a collaborative assessment of tribal needs regarding heritage concerns. Then, together with tribes, an archaeological site was selected to be the focus of the archaeological field school. It is important to note that only sites deemed suitable by participant tribal organizations were considered during this process. Potential sites considered were either already in need of mitigation due to imminent threat of development or sites that a tribal organization determined would benefit their heritage needs. Specific areas of the Stewart Indian School were selected because the Nevada Indian Commission, the Stewart Advisory Committee, and the Washoe THPO determined that an archaeological field school had the potential to benefit several of their upcoming heritage needs. In addition, it was desirable to many tribal members that we choose a site that would benefit multiple tribes by educating the American public about the traumatic effects of forced assimilation faced by many American Indians. Project collaborators then began contributing to the field school planning, which was conducted in summer 2013. Project personnel worked with tribal consultants in a collaborative, involved exchange of ideas, which occurred both on-site and at off-site locations. Tribal consultants lead heritage discussions at the field school and contributed to the professionalization of both Native and non-Native students. After the field work was completed, lab work and artifact processing continued through the fall and spring semesters in consultation with tribal members. The project finished with writing results and requesting essays from participants, and eventually circulating drafts of this volume to all participants for comment and revisions.

We hope the final result here provides not only a community-based case study of an important site, but also some insights into broader heritage issues. Ultimately, this project’s goal focused on outlining a strategy for humanizing the process of respectful consultation among tribes, archaeologists, and the federal government. This is accomplished by applying theories of multivocality, governmentalization, agency, and social capital to a qualitative analysis of the impasse in federal/tribal discourses around consultation. In doing so, we offer some potential solutions to address the impasse to help the federal government more fully meet federal trust responsibility obligations, and to encourage archaeologists in public, state, and academic sectors to decolonize methods and recognize tribal members as productive colleagues who share concerns for heritage.

The woman who initially reprimanded us began to weep as she told us her story. We were in the midst of a collaborative archaeological field school at the site of Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada, with a great deal of involvement from tribal members from multiple tribes, many of whom had members that passed through Stewart, as this alumna had, during its complicated ninety-year history as an off-reservation boarding school in Nevada. Like many other alumni and community members, she had heard about our widely advertised project and was visiting Stewart, as many alumni do on a semiregular basis, to reconnect with the place and the memories associated with it. She had been shouting at us from a distance as she passed by, saying that we didn’t know what we were getting into with excavating this place, that terrible things had happened here, and that we should leave such things alone. This is a common sentiment among many American Indians about archaeology in general, that things left by people in the past are too powerful to tamper with, especially things associated with negative experiences. Most people that talked to us about the project were either supportive or curious, but occasionally someone expressed concern. One tribe’s attorney contacted us, concerned that we might excavate graves of children who had died at the school, assuming that digging up graves was archaeologists’ primary occupation. On each of these interactions we had the opportunity to learn more about the school and what it meant to alumni, their families, and their tribes, as well as the history of the federal government’s attempt to forcibly assimilate Native Americans. We also had the opportunity to do better archaeology through public involvement, train students in a multivocal and collaborative approach to archaeological field methods, and demonstrate that archaeologists are not always grave robbers.

As this alumna was admonishing us, we might have ignored her, and continued our excavations as she passed by. But being a public archaeology project designed to learn from tribal members, instead we tentatively approached her and listened.

Her story was a complicated one, as many stories of this place are. There is so much sorrow and trauma here associated with the practices and repercussions of attempted assimilation. But she also wept as she described her childhood, in which her parents could not care for her, and how she wanted to attend Stewart to be a part of that community. She wept as she explained how important this place was to her; good and bad, it was her home. She said more people should know about Stewart Indian School’s significance, and agreed that our collaborative project might help raise awareness of Native peoples’ experiences there. She embraced some of us who listened to her story, and then she went on her way, walking to another part of campus with her memories.

Who could not be moved by such an experience? This interaction was typical on this project; it and many others humanized the experience of conducting archaeology here. It shows how place-based learning evokes knowledge and memories that are not so accessible elsewhere. It also exemplifies how valuing human relations can overcome seemingly conflicting worldviews, for example, between science and spirituality, or between federal heritage laws and a personal sense of what is right. Such discussions are critical to building relationships, and providing space for historically suppressed voices to tell their truths. Throughout this volume, our work is guided by a large body of literature on decolonizing methods and Indigenous archaeology, with inspiration from Native archaeologists working in their communities and guidance from foundational scholarship in Indigenous heritage studies (e.g., Atalay 2006, 2012; Colwell 2016; Deloria 1969; Dongoske et al. 2000; Ferguson and Colwell-Chanthaphonh 2006; Gould 2013; Gonzales et al. 2018; Laluk 2017; Martinez and Teeter 2015; Nicholas 2010; Schneider 2018; Silliman 2008; Smith 1999; Smith and Wobst 2005; Thomspon 2011; Teeman 2008; Two Bears 2010; Watkins 2000).

We combine many voices in this volume: Native and non-Native; elder and younger; academic, traditional, scientific, and personal. This created a manuscript that is multivocal and shifting in voice, with varied perspectives that may or may not mesh precisely with one another. We hope readers can appreciate the necessity of presenting different discourses in collaboration with each other and have patience with our approach. The result is that we are able to address a wide variety of topics and put them in conversation with each other.

Goals for the Stewart Indian School Project

Goals and objectives for the project were to study the interplay of tribal agency, social capital, and governmentalized archaeological discourse, and then outline a strategy for humanizing the process of respectful consultation among tribes, archaeologists, and the federal government. The project was funded by a three-year grant from the Army Research Office’s Young Investigator’s Program (Sarah Cowie, principle investigator) with the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR), in partnership with The Nevada Indian Commission, the Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) and numerous other Native and non-Native heritage specialists, volunteers, students, staff, and community members, many of whom are contributing authors to this volume.

Together we observed and researched areas where conflict arises, why there is still an impasse in conflicting discourses, and how governmentalization both helps and hinders processes of consultation. In chronicling this project’s archaeological practice and collaboration with tribal heritage specialists, this volume suggests some opportunities for building social capital and collaborating with tribes. From this work we found that it is possible to shift discourse around consultation to improve satisfaction of outcomes for all parties, at least in this particular case study.

This project involved a qualitative study of the impasse in federal/tribal discourses regarding heritage consultation. A network of partners collaboratively developed a model for improved consultation procedures. This volume, one of the results of the overall project, addresses the repercussions of federal government discourse surrounding Indigenous heritage and the utility of social capital for improving communication. The non-Native archaeologists who initiated the project organized a series of heritage discussions with tribal members who served as tribal consultants or partners in a collaborative, involved exchange of ideas. Tribal members participated as professional heritage specialists, staff, policy makers, and university academics, as well as undergraduate students that participated in the collaborative archaeological field school. In this case, fieldwork served as a foundation for discussing the improvement of tribal/federal heritage management issues. This strategy is informed by practice theory; phenomenology; and the linkages between place, memory, and multivocality that are valued by many tribal peoples (e.g., Basso 1996; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson 2006; Cowie et al. 2009), as well as recent pedagogical shifts in teaching collaborative archaeology (e.g., Silliman 2008).

Personnel working on this project worked collaboratively as equal contributors, rather than as subjects in data gathering. Each participant contributed his/her own knowledge about the topic. The UNR Office of Human Research Protection determined that this project did not constitute research on human subjects and was therefore exempt from human subjects review.

The proposed model for this project hinged on the idea that tribal/federal relationships could be improved by establishing relationships before the consultation process formally began; networks would then already be in place before potentially contentious issues arose. Federal agencies would make a minimal investment through heritage outreach activities first, not waiting until there is a problem to consult with tribes. The goal is for open dialog to continue productively when contentious heritage issues eventually arise.

Outreach activities during this project included collaborative work with several tribes and tribal heritage staff in Nevada and Oregon to deconstruct the current consultation process and to assess the ramifications of federally governmentalized discourse. In addition, this study models a heritage project that integrates both federal and Native discourses, in the form of a good faith offer of services to tribes for the mutual, long-term benefit of federal agencies as well as tribes. Services might include facilitating tribal visits to their traditional homelands on federally managed lands, and offering archaeological training and services to tribal entities. This project included funding for tribal undergraduate students to participate in the archaeological field school, and a number of Native consultants were hired for their expertise on various portions of the project. Other tribal members who work in heritage careers also participated in fieldwork as well, creating a productive exchange of ideas for Native and non-Native peoples and building social capital.

This three-year project began in the summer of 2012. Project participants reviewed the large body of literature regarding heritage consultation in both federal and Indigenous discourses. The literature was analyzed within the context of governmentality and agency theories. In the second year of the project personnel networked with tribal heritage specialists who were interested in participating and began a collaborative assessment of tribal needs regarding heritage concerns. Then, together with tribes, an archaeological site was selected to be the focus of the archaeological field school. It is important to note that only sites deemed suitable by participant tribal organizations were considered during this process. Potential sites considered were either already in need of mitigation due to imminent threat of development or sites that a tribal organization determined would benefit their heritage needs. Specific areas of the Stewart Indian School were selected because the Nevada Indian Commission, the Stewart Advisory Committee, and the Washoe THPO determined that an archaeological field school had the potential to benefit several of their upcoming heritage needs. In addition, it was desirable to many tribal members that we choose a site that would benefit multiple tribes by educating the American public about the traumatic effects of forced assimilation faced by many American Indians. Project collaborators then began contributing to the field school planning, which was conducted in summer 2013. Project personnel worked with tribal consultants in a collaborative, involved exchange of ideas, which occurred both on-site and at off-site locations. Tribal consultants lead heritage discussions at the field school and contributed to the professionalization of both Native and non-Native students. After the field work was completed, lab work and artifact processing continued through the fall and spring semesters in consultation with tribal members. The project finished with writing results and requesting essays from participants, and eventually circulating drafts of this volume to all participants for comment and revisions.

We hope the final result here provides not only a community-based case study of an important site, but also some insights into broader heritage issues. Ultimately, this project’s goal focused on outlining a strategy for humanizing the process of respectful consultation among tribes, archaeologists, and the federal government. This is accomplished by applying theories of multivocality, governmentalization, agency, and social capital to a qualitative analysis of the impasse in federal/tribal discourses around consultation. In doing so, we offer some potential solutions to address the impasse to help the federal government more fully meet federal trust responsibility obligations, and to encourage archaeologists in public, state, and academic sectors to decolonize methods and recognize tribal members as productive colleagues who share concerns for heritage.

Cuprins

Foreword: Digging into Indian Education

Joe Watkins

A Multivocal Collaboration Story

Sarah E. Cowie, Diane L. Teeman, Christopher C. LeBlanc, Terri McBride, and Ashley M. Long

Theoretical Approaches to Collaborative Archaeology

Diane L. Teeman, Sarah E. Cowie, Christopher C. LeBlanc and Ashley M. Long

Consensus in Research Design, and Studying Institutions, Education, and Childhood

Ashley M. Long, Sarah E. Cowie, and Christopher C. LeBlanc

Indian Education in Nevada (1890–2015): A Legacy of Change

Alex K. Ruuska

History and Daily Life at the Stewart Campus

Bonnie Thompson-Hardin

Stewart Indian School Methods and Research Results

Ashley M. Long, Sarah E. Cowie, and Ian Springer

Reflexive, Multivocal Interpretations of Stewart Indian School, and Best Practices in Heritage Management

Richard Arnold, Patrick Burtt, Sarah E. Cowie, Darrel Cruz, Eric DeSoto, Debra Harry, A. J. Johnson, Mark Johnson, Dania Jordan, Christopher C. LeBlanc, Ashley M. Long, Jo Ann Nevers, Sherry L. Rupert and Chris A. Gibbons, Diane L. Teeman, and Lonnie P. Teeman, Sr.

Concluding Lessons from Stewart Indian School: Governmentality and Social Capital in Best Practices

Diane L. Teeman, Sarah E. Cowie, Terri McBride, Ashley M. Long, and Christopher C. LeBlanc

Acknowledgments

About the Contributors

Joe Watkins

A Multivocal Collaboration Story

Sarah E. Cowie, Diane L. Teeman, Christopher C. LeBlanc, Terri McBride, and Ashley M. Long

Theoretical Approaches to Collaborative Archaeology

Diane L. Teeman, Sarah E. Cowie, Christopher C. LeBlanc and Ashley M. Long

Consensus in Research Design, and Studying Institutions, Education, and Childhood

Ashley M. Long, Sarah E. Cowie, and Christopher C. LeBlanc

Indian Education in Nevada (1890–2015): A Legacy of Change

Alex K. Ruuska

History and Daily Life at the Stewart Campus

Bonnie Thompson-Hardin

Stewart Indian School Methods and Research Results

Ashley M. Long, Sarah E. Cowie, and Ian Springer

Reflexive, Multivocal Interpretations of Stewart Indian School, and Best Practices in Heritage Management

Richard Arnold, Patrick Burtt, Sarah E. Cowie, Darrel Cruz, Eric DeSoto, Debra Harry, A. J. Johnson, Mark Johnson, Dania Jordan, Christopher C. LeBlanc, Ashley M. Long, Jo Ann Nevers, Sherry L. Rupert and Chris A. Gibbons, Diane L. Teeman, and Lonnie P. Teeman, Sr.

Concluding Lessons from Stewart Indian School: Governmentality and Social Capital in Best Practices

Diane L. Teeman, Sarah E. Cowie, Terri McBride, Ashley M. Long, and Christopher C. LeBlanc

Acknowledgments

About the Contributors

Descriere

Collaborative Archaeology Stewart Indian School tells the story of Stewart Indian School in Nevada and the resilience of Native communities, with a multivocal approach to indigenous archaeology. From start to finish, this project has been a joint effort of University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada Indian Commission, and Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office, including 21 contributing authors, over half of which are tribal members (primarily Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone).