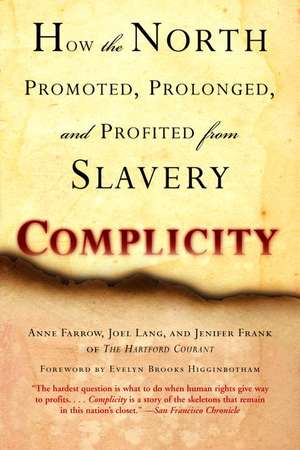

Complicity: How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery

Autor Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, Jenifer Franken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2006

Complicity reveals the cruel truth about the Triangle Trade of molasses, rum, and slaves that lucratively linked the North to the West Indies and Africa; discloses the reality of Northern empires built on profits from rum, cotton, and ivory–and run, in some cases, by abolitionists; and exposes the thousand-acre plantations that existed in towns such as Salem, Connecticut. Here, too, are eye-opening accounts of the individuals who profited directly from slavery far from the Mason-Dixon line–including Nathaniel Gordon of Maine, the only slave trader sentenced to die in the United States, who even as an inmate of New York’s infamous Tombs prison was supported by a shockingly large percentage of the city; Patty Cannon, whose brutal gang kidnapped free blacks from Northern states and sold them into slavery; and the Philadelphia doctor Samuel Morton, eminent in the nineteenth-century field of “race science,” which purported to prove the inferiority of African-born black people.

Culled from long-ignored documents and reports–and bolstered by rarely seen photos, publications, maps, and period drawings–Complicity is a fascinating and sobering work that actually does what so many books pretend to do: shed light on America’s past. Expanded from the celebrated Hartford Courant special report that the Connecticut Department of Education sent to every middle school and high school in the state (the original work is required readings in many college classrooms,) this new book is sure to become a must-read reference everywhere.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 79.25 lei

Preț vechi: 94.88 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 119

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.16€ • 15.83$ • 12.55£

15.16€ • 15.83$ • 12.55£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345467836

ISBN-10: 0345467833

Pagini: 269

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS, MAPS,LINE DRAWINGS

Dimensiuni: 137 x 208 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345467833

Pagini: 269

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOS, MAPS,LINE DRAWINGS

Dimensiuni: 137 x 208 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank are veteran journalists for The Hartford Courant, the country’s oldest newspaper in continuous publication. Farrow and Lang were the lead writers and Frank was the editor of the special slavery issue published by Northeast, the newspaper’s Sunday magazine.

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of History and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She is co-editor with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of African American Lives.

From the Hardcover edition.

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of History and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She is co-editor with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of African American Lives.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

COTTON COMES NORTH

“The ships would rot at her docks; grass would grow in Wall Street and Broadway, and the glory of New York, like that of Babylon and Rome, would be numbered with the things of the past.”

The answer given by a prominent Southern editor when asked by The Times (London), “What would New York be without slavery?”

Fernando Wood thought his timing was perfect.

The election of an antislavery president had finally forced the South to make good on years of threats, and the exodus of 11 states from the Union had begun. Militant South Carolina was the first to secede, after a convention in Charleston five days before Christmas of 1860. Within weeks, 6 more states had broken off from the Union, and by the end of May, the Confederacy was complete.

As the most profound crisis in our young nation’s history unrolled, Wood, the mayor of New York, America’s most powerful city, made a stunning proposal: New York City should secede from the United States, too.

“With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy,” Wood told the New York Common Council in his State of the City message on January 7, 1861. “As a free city,” he said, New York “would have the whole and united support of the Southern States, as well as all other States to whose interests and rights under the constitution she has always been true.”

Although many in the city’s intelligentsia rolled their eyes, and the mayor was slammed in much of the New York press, Wood’s proposal made a certain kind of sense. The mayor was reacting to tensions with Albany, but there was far more behind his secession proposal, particularly if one understood that the lifeblood of New York City’s economy was cotton, the product most closely identified with the South and its defining system of labor: the slavery of millions of people of African descent.

Slave-grown cotton is, in large part, the root of New York’s wealth. Forty years before Fernando Wood suggested that New York join hands with the South and leave the Union, cotton had already become the nation’s number one exported product. And in the four intervening decades New York had

become a commercial and financial behemoth dwarfing any other U.S. city and most others in the world. Cotton was more than just a profitable crop. It was the national currency, the product most responsible for America’s explosive growth in the decades before the Civil War.

As much as it is linked to the barbaric system of slave labor that raised it, cotton created New York.

By the eve of the war, hundreds of businesses in New York, and countless more throughout the North, were connected to, and dependent upon, cotton. As New York became the fulcrum of the U.S. cotton trade, merchants, shippers, auctioneers, bankers, brokers, insurers, and thousands of others were drawn to the burgeoning urban center. They packed lower Manhattan, turning it into the nation’s emporium, in which products from all over the world were traded.

In those prewar decades, hundreds of shrewd merchants and smart businessmen made their fortunes in ventures directly or indirectly tied to cotton. The names of some of them reverberate today.

Three brothers named Lehman were cotton brokers in Montgomery, Alabama, before they moved to New York and helped to establish the New York Cotton Exchange. Today, of course, Lehman Brothers is the international investment firm.

Junius Morgan, father of J. Pierpont Morgan, arranged for his son to study the cotton trade in the South as the future industrialist and banker was beginning his business career. Morgan Sr., a Massachusetts native who became a major banker and cotton broker in London, understood that knowledge of the cotton trade was essential to prospering in the commercial world in the 1850s.

Real estate and shipping magnate John Jacob Astor—one of America’s first millionaires and namesake of the Waldorf-Astoria and whole neighborhoods in New York City—made his fortune in furs and the China trade. But Astor’s ships, like those of many successful merchant-shippers, also carried tons of cotton.

Cotton’s rich threads can even be traced to an ambitious young man who dreamed of opening a “fancy goods” store in New York. The young man’s father, who operated a cotton mill in eastern Connecticut, gave his son the money to open his first store, on Broadway, in 1837. But more important than the $500 stake made from cotton was the young man’s destination and timing: Charles L. Tiffany had begun serving a city in extraordinary, and enduring, economic ascent.

As with any commodity, trading in cotton was complicated and risky. Businessmen, even savvy ones, lost fortunes, but some made their mark on the city nonetheless.

As cotton was becoming a staple in the transatlantic trade, Scotsman Archibald Gracie immigrated to New York after training in Liverpool, Great Britain’s great cotton port. Gracie became an international shipping magnate, a merchant prince, building a summer home on the East River before losing much of his wealth. His son and grandson left the city to become cotton brokers in Mobile, Alabama, but their family’s summer home, today called Gracie Mansion, is the official residence of the mayor of New York.

But beyond identifying the individuals who prospered from the South’s most important product, it’s vital to understand the economic climate—the vast opportunities for wealth that the cotton trade created, and that linked New York City so tightly to the South. Before the Civil War, the city’s fortunes, its very future, were considered by many to be inseparable from those of the cotton-producing states.

Secession was not even an original thought with Wood, a tall, charming, three-term scoundrel of a mayor and multiterm congressman. For years, members of New York’s business community had mused privately, and occasionally in the pages of journals, that the city would be better off as a “free port,” independent of tariff-levying politicians in Albany and Washington. As America unraveled over the issue of slavery, many Northern politicians and businessmen became frantic to reach out to their most important constituency: Southern planters.

New York was not the only area in the North whose future was threatened by the growing secession crisis. In Massachusetts, birthplace of America, and the center of an increasingly troublesome movement called abolitionism, the Southern states’ frequent threats to secede had become an ongoing nightmare for the leaders of the powerful textile industry.

By 1860, New England was home to 472 cotton mills, built on rivers and streams throughout the region. The town of Thompson, Connecticut, alone, for example, had seven mills within its nine-square-mile area. Hundreds of other textile mills were scattered in New York State, New Jersey, and elsewhere in the North. Just between 1830 and 1840, Northern mills consumed more than 100 million pounds of Southern cotton. With shipping and manufacturing included, the economy of much of New England was connected to textiles.

For years, the national dispute over slavery had been growing more and more alarming to the powerful group of Massachusetts businessmen that historians refer to as the Boston Associates. When this handful of brilliant industrialists established America’s textile industry earlier in the nineteenth century, they also created America’s own industrial revolution. By the 1850s, their enormous profits had been poured into a complex network of banks, insurance companies, and railroads. But their wealth remained anchored to dozens of mammoth textile mills in Massachusetts, southern Maine, and New Hampshire. Some of these places were textile cities, really—like Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, both named for Boston Associates founders.

As the nation lurched toward war and the certainty of economic disruption, these industrialists and allied politicians wanted to convince the South that at least some in the North were eager to compromise

on slavery. A compromise was critical, for the good of the Union and business.

On the evening of October 11, 1858, a standing-room-only audience of politicians and businessmen honored a visitor at a rally at Faneuil Hall, long the center of Boston’s public life. The wealthy and powerful of New England’s preeminent city lauded the “intellectual cultivation” and “eloquence” of the senator from Mississippi, and when Jefferson Davis walked onto the stage, the Brahmins of Boston gave him a standing ovation.

Other American staples, such as corn, wheat, and tobacco, have a charged or even exalted status in our nation’s narrative. And other resources—whale oil, coal, and gold—were the main characters in defining chapters of American history.

But cotton was king.

On the cusp of the Civil War, the 10 major cotton states were producing 66 percent of the world’s cotton, and raw cotton accounted for more than half of all U.S. exports. The numbers are almost impossible to grasp: in the season that ended on August 31, 1860, the United States produced close to 5 million bales of cotton, or roughly 2.3 billion pounds. Of that amount, it exported about half—or more than 1 billion pounds—to Great Britain’s 2,650 cotton factories.

By then, the Industrial Revolution had spread throughout Europe. Although small compared with Great Britain’s, France’s textile industry, centered in Lille, was also fed almost entirely by U.S. cotton, 200 million pounds’ worth in 1858. And Southern cotton was important to textile industries in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy, Spain, and Belgium.

But most of the world’s cotton went through Liverpool, the port nearest Manchester in Lancashire, the heart of textile manufacturing. Up until the end of the 1700s, Great Britain had imported most of its cotton from the Mediterranean, its colonies in the West Indies, and India and Brazil. But in 1794 Eli Whitney, the son of a Massachusetts farmer, patented his cotton gin (invented the previous year), and it changed the world.

The problem with cotton is its seeds. Nestled deep in the fibers of every fist-sized boll of upland cotton—the predominant type grown in America—are 30 to 40 impossibly sticky green seeds that must be removed before the white, fluffy fibers can be used.

Before Whitney patented his gin, it took one person an entire day to remove the seeds from a pound of cotton. The gin both mechanized and accelerated the process. The teeth of a series of circular saws “captured” the seeds, allowing the fibers to be pulled away from them. The device increased the production of cleaned cotton an astonishing fiftyfold. In seeking a patent for his invention, Whitney wrote to Thomas Jefferson, then secretary of state, explaining that by using the gin, “one negro [could] . . . clean fifty weight (I mean fifty pounds after it is separated from the seed), of the green seed cotton per day.” Jefferson was one of the first plantation owners to order a gin.

Growing cotton suddenly became hugely profitable. Farmers across the South switched over to cotton, and within only about 15 years they were supplying more than half of Great Britain’s demand for the product. Well before 1860, the relationship between Great Britain and the South had become ironclad.

A lot of cotton required a lot of slaves. In 1850, some 2.3 million people were enslaved in the 10 cotton states; of these, nearly 2 million were involved in some aspect of cotton production. And their numbers, and importance, just kept growing.

As early as 1836, the secretary of the treasury told Congress that with “less than 100,000 more field hands” and the conversion of just 500,000 more acres of rich Southern land, the United States could produce enough raw cotton for the entire world.

By the eve of the Civil War, Great Britain was largely clothing the Western world, using Southern-grown, slave-picked cotton.

In 1850, the South was home to about 75,000 cotton plantations. Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia each had over 14,500. The cotton states produced a staggering 2 million bales that year. Even people who saw the trade in action struggled to describe it.

In December 1848, Solon Robinson, a farmer and writer from Connecticut who became agriculture editor for the New York Tribune, visited the nation’s largest cotton port. “It must be seen to be believed,” Robinson wrote of the “acres of cotton bales” standing on the docks of New Orleans. “Boats are constantly arriving, so piled up with cotton, that the lower tier of bales on deck are in the water; and as the boat is approaching, it looks like a huge raft of cotton bales, with the chimneys and steam pipe of an engine sticking up out of the centre.”

From New Orleans and the other major cotton ports—Savannah, Georgia; Charleston, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama—most of the cotton was shipped to Liverpool. If it did not go directly to Liverpool, it was sent to the North: to Boston for use in the domestic textile industry, or to New York City. From New York, it generally went to Liverpool, or elsewhere in Europe.

But this gives only the slightest hint of the role New York City and the rest of the North played in the cotton trade, or of the lengths the New York business community was forced to go to protect its franchise.

The Union Committee of Fifteen had called a meeting at the offices of Richard Lathers, a prominent cotton merchant. The organizers had planned to invite 200 people, and by written invitation only. But the group that thronged outside of Lathers’s offices at 33 Pine Street, a block over from Wall Street, surpassed 2,000. In fact, offices across the street had to be quickly commandeered to accommodate the crowd, and even then the merchants, bankers, and others who gathered that Saturday afternoon spilled into the street.

This was hardly the first time that the worried business community had met to discuss strategies to smooth relations between North and South. But the Pine Street meeting on December 15, 1860, may have represented the group at its most panicky. South Carolina’s probable secession vote was days away, and there was talk of Alabama following South Carolina. After that, who knew? The South had to be persuaded to stay in the Union until some kind of compromise in the slavery controversy could be found.

The very spine of nineteenth-century money and power attended the meeting. These “merchant princes” included:

•A. T. Stewart, a cotton merchant who opened the nation’s first department store, called “the marble palace,” on Broadway. Stewart was thought to be the wealthiest man in New York.

•Moses Taylor, sugar importer, banker, and coal and railroad magnate, whose extensive enterprises made him, for nearly half a century, one of the most influential businessmen in New York City.

•Abiel Abbot Low, whose A. A. Low & Brothers was the most important firm in the new and booming China trade.

•William B. Astor, son of fur and real estate mogul John Jacob Astor, the nation’s first millionaire.

•Wall Street banker August Belmont, American agent for the Rothschilds of Germany, who married the daughter of Commodore Perry and whose passion for horse breeding led to the creation of the Belmont Stakes.

From the Hardcover edition.

COTTON COMES NORTH

“The ships would rot at her docks; grass would grow in Wall Street and Broadway, and the glory of New York, like that of Babylon and Rome, would be numbered with the things of the past.”

The answer given by a prominent Southern editor when asked by The Times (London), “What would New York be without slavery?”

Fernando Wood thought his timing was perfect.

The election of an antislavery president had finally forced the South to make good on years of threats, and the exodus of 11 states from the Union had begun. Militant South Carolina was the first to secede, after a convention in Charleston five days before Christmas of 1860. Within weeks, 6 more states had broken off from the Union, and by the end of May, the Confederacy was complete.

As the most profound crisis in our young nation’s history unrolled, Wood, the mayor of New York, America’s most powerful city, made a stunning proposal: New York City should secede from the United States, too.

“With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States, we have friendly relations and a common sympathy,” Wood told the New York Common Council in his State of the City message on January 7, 1861. “As a free city,” he said, New York “would have the whole and united support of the Southern States, as well as all other States to whose interests and rights under the constitution she has always been true.”

Although many in the city’s intelligentsia rolled their eyes, and the mayor was slammed in much of the New York press, Wood’s proposal made a certain kind of sense. The mayor was reacting to tensions with Albany, but there was far more behind his secession proposal, particularly if one understood that the lifeblood of New York City’s economy was cotton, the product most closely identified with the South and its defining system of labor: the slavery of millions of people of African descent.

Slave-grown cotton is, in large part, the root of New York’s wealth. Forty years before Fernando Wood suggested that New York join hands with the South and leave the Union, cotton had already become the nation’s number one exported product. And in the four intervening decades New York had

become a commercial and financial behemoth dwarfing any other U.S. city and most others in the world. Cotton was more than just a profitable crop. It was the national currency, the product most responsible for America’s explosive growth in the decades before the Civil War.

As much as it is linked to the barbaric system of slave labor that raised it, cotton created New York.

By the eve of the war, hundreds of businesses in New York, and countless more throughout the North, were connected to, and dependent upon, cotton. As New York became the fulcrum of the U.S. cotton trade, merchants, shippers, auctioneers, bankers, brokers, insurers, and thousands of others were drawn to the burgeoning urban center. They packed lower Manhattan, turning it into the nation’s emporium, in which products from all over the world were traded.

In those prewar decades, hundreds of shrewd merchants and smart businessmen made their fortunes in ventures directly or indirectly tied to cotton. The names of some of them reverberate today.

Three brothers named Lehman were cotton brokers in Montgomery, Alabama, before they moved to New York and helped to establish the New York Cotton Exchange. Today, of course, Lehman Brothers is the international investment firm.

Junius Morgan, father of J. Pierpont Morgan, arranged for his son to study the cotton trade in the South as the future industrialist and banker was beginning his business career. Morgan Sr., a Massachusetts native who became a major banker and cotton broker in London, understood that knowledge of the cotton trade was essential to prospering in the commercial world in the 1850s.

Real estate and shipping magnate John Jacob Astor—one of America’s first millionaires and namesake of the Waldorf-Astoria and whole neighborhoods in New York City—made his fortune in furs and the China trade. But Astor’s ships, like those of many successful merchant-shippers, also carried tons of cotton.

Cotton’s rich threads can even be traced to an ambitious young man who dreamed of opening a “fancy goods” store in New York. The young man’s father, who operated a cotton mill in eastern Connecticut, gave his son the money to open his first store, on Broadway, in 1837. But more important than the $500 stake made from cotton was the young man’s destination and timing: Charles L. Tiffany had begun serving a city in extraordinary, and enduring, economic ascent.

As with any commodity, trading in cotton was complicated and risky. Businessmen, even savvy ones, lost fortunes, but some made their mark on the city nonetheless.

As cotton was becoming a staple in the transatlantic trade, Scotsman Archibald Gracie immigrated to New York after training in Liverpool, Great Britain’s great cotton port. Gracie became an international shipping magnate, a merchant prince, building a summer home on the East River before losing much of his wealth. His son and grandson left the city to become cotton brokers in Mobile, Alabama, but their family’s summer home, today called Gracie Mansion, is the official residence of the mayor of New York.

But beyond identifying the individuals who prospered from the South’s most important product, it’s vital to understand the economic climate—the vast opportunities for wealth that the cotton trade created, and that linked New York City so tightly to the South. Before the Civil War, the city’s fortunes, its very future, were considered by many to be inseparable from those of the cotton-producing states.

Secession was not even an original thought with Wood, a tall, charming, three-term scoundrel of a mayor and multiterm congressman. For years, members of New York’s business community had mused privately, and occasionally in the pages of journals, that the city would be better off as a “free port,” independent of tariff-levying politicians in Albany and Washington. As America unraveled over the issue of slavery, many Northern politicians and businessmen became frantic to reach out to their most important constituency: Southern planters.

New York was not the only area in the North whose future was threatened by the growing secession crisis. In Massachusetts, birthplace of America, and the center of an increasingly troublesome movement called abolitionism, the Southern states’ frequent threats to secede had become an ongoing nightmare for the leaders of the powerful textile industry.

By 1860, New England was home to 472 cotton mills, built on rivers and streams throughout the region. The town of Thompson, Connecticut, alone, for example, had seven mills within its nine-square-mile area. Hundreds of other textile mills were scattered in New York State, New Jersey, and elsewhere in the North. Just between 1830 and 1840, Northern mills consumed more than 100 million pounds of Southern cotton. With shipping and manufacturing included, the economy of much of New England was connected to textiles.

For years, the national dispute over slavery had been growing more and more alarming to the powerful group of Massachusetts businessmen that historians refer to as the Boston Associates. When this handful of brilliant industrialists established America’s textile industry earlier in the nineteenth century, they also created America’s own industrial revolution. By the 1850s, their enormous profits had been poured into a complex network of banks, insurance companies, and railroads. But their wealth remained anchored to dozens of mammoth textile mills in Massachusetts, southern Maine, and New Hampshire. Some of these places were textile cities, really—like Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, both named for Boston Associates founders.

As the nation lurched toward war and the certainty of economic disruption, these industrialists and allied politicians wanted to convince the South that at least some in the North were eager to compromise

on slavery. A compromise was critical, for the good of the Union and business.

On the evening of October 11, 1858, a standing-room-only audience of politicians and businessmen honored a visitor at a rally at Faneuil Hall, long the center of Boston’s public life. The wealthy and powerful of New England’s preeminent city lauded the “intellectual cultivation” and “eloquence” of the senator from Mississippi, and when Jefferson Davis walked onto the stage, the Brahmins of Boston gave him a standing ovation.

Other American staples, such as corn, wheat, and tobacco, have a charged or even exalted status in our nation’s narrative. And other resources—whale oil, coal, and gold—were the main characters in defining chapters of American history.

But cotton was king.

On the cusp of the Civil War, the 10 major cotton states were producing 66 percent of the world’s cotton, and raw cotton accounted for more than half of all U.S. exports. The numbers are almost impossible to grasp: in the season that ended on August 31, 1860, the United States produced close to 5 million bales of cotton, or roughly 2.3 billion pounds. Of that amount, it exported about half—or more than 1 billion pounds—to Great Britain’s 2,650 cotton factories.

By then, the Industrial Revolution had spread throughout Europe. Although small compared with Great Britain’s, France’s textile industry, centered in Lille, was also fed almost entirely by U.S. cotton, 200 million pounds’ worth in 1858. And Southern cotton was important to textile industries in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy, Spain, and Belgium.

But most of the world’s cotton went through Liverpool, the port nearest Manchester in Lancashire, the heart of textile manufacturing. Up until the end of the 1700s, Great Britain had imported most of its cotton from the Mediterranean, its colonies in the West Indies, and India and Brazil. But in 1794 Eli Whitney, the son of a Massachusetts farmer, patented his cotton gin (invented the previous year), and it changed the world.

The problem with cotton is its seeds. Nestled deep in the fibers of every fist-sized boll of upland cotton—the predominant type grown in America—are 30 to 40 impossibly sticky green seeds that must be removed before the white, fluffy fibers can be used.

Before Whitney patented his gin, it took one person an entire day to remove the seeds from a pound of cotton. The gin both mechanized and accelerated the process. The teeth of a series of circular saws “captured” the seeds, allowing the fibers to be pulled away from them. The device increased the production of cleaned cotton an astonishing fiftyfold. In seeking a patent for his invention, Whitney wrote to Thomas Jefferson, then secretary of state, explaining that by using the gin, “one negro [could] . . . clean fifty weight (I mean fifty pounds after it is separated from the seed), of the green seed cotton per day.” Jefferson was one of the first plantation owners to order a gin.

Growing cotton suddenly became hugely profitable. Farmers across the South switched over to cotton, and within only about 15 years they were supplying more than half of Great Britain’s demand for the product. Well before 1860, the relationship between Great Britain and the South had become ironclad.

A lot of cotton required a lot of slaves. In 1850, some 2.3 million people were enslaved in the 10 cotton states; of these, nearly 2 million were involved in some aspect of cotton production. And their numbers, and importance, just kept growing.

As early as 1836, the secretary of the treasury told Congress that with “less than 100,000 more field hands” and the conversion of just 500,000 more acres of rich Southern land, the United States could produce enough raw cotton for the entire world.

By the eve of the Civil War, Great Britain was largely clothing the Western world, using Southern-grown, slave-picked cotton.

In 1850, the South was home to about 75,000 cotton plantations. Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia each had over 14,500. The cotton states produced a staggering 2 million bales that year. Even people who saw the trade in action struggled to describe it.

In December 1848, Solon Robinson, a farmer and writer from Connecticut who became agriculture editor for the New York Tribune, visited the nation’s largest cotton port. “It must be seen to be believed,” Robinson wrote of the “acres of cotton bales” standing on the docks of New Orleans. “Boats are constantly arriving, so piled up with cotton, that the lower tier of bales on deck are in the water; and as the boat is approaching, it looks like a huge raft of cotton bales, with the chimneys and steam pipe of an engine sticking up out of the centre.”

From New Orleans and the other major cotton ports—Savannah, Georgia; Charleston, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama—most of the cotton was shipped to Liverpool. If it did not go directly to Liverpool, it was sent to the North: to Boston for use in the domestic textile industry, or to New York City. From New York, it generally went to Liverpool, or elsewhere in Europe.

But this gives only the slightest hint of the role New York City and the rest of the North played in the cotton trade, or of the lengths the New York business community was forced to go to protect its franchise.

The Union Committee of Fifteen had called a meeting at the offices of Richard Lathers, a prominent cotton merchant. The organizers had planned to invite 200 people, and by written invitation only. But the group that thronged outside of Lathers’s offices at 33 Pine Street, a block over from Wall Street, surpassed 2,000. In fact, offices across the street had to be quickly commandeered to accommodate the crowd, and even then the merchants, bankers, and others who gathered that Saturday afternoon spilled into the street.

This was hardly the first time that the worried business community had met to discuss strategies to smooth relations between North and South. But the Pine Street meeting on December 15, 1860, may have represented the group at its most panicky. South Carolina’s probable secession vote was days away, and there was talk of Alabama following South Carolina. After that, who knew? The South had to be persuaded to stay in the Union until some kind of compromise in the slavery controversy could be found.

The very spine of nineteenth-century money and power attended the meeting. These “merchant princes” included:

•A. T. Stewart, a cotton merchant who opened the nation’s first department store, called “the marble palace,” on Broadway. Stewart was thought to be the wealthiest man in New York.

•Moses Taylor, sugar importer, banker, and coal and railroad magnate, whose extensive enterprises made him, for nearly half a century, one of the most influential businessmen in New York City.

•Abiel Abbot Low, whose A. A. Low & Brothers was the most important firm in the new and booming China trade.

•William B. Astor, son of fur and real estate mogul John Jacob Astor, the nation’s first millionaire.

•Wall Street banker August Belmont, American agent for the Rothschilds of Germany, who married the daughter of Commodore Perry and whose passion for horse breeding led to the creation of the Belmont Stakes.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Rich with historical documents and photos, this narrative dispels the myths surrounding the history of slavery in this country, revealing the North's deep dependence on slave commerce and its own exploitation of slave labor.