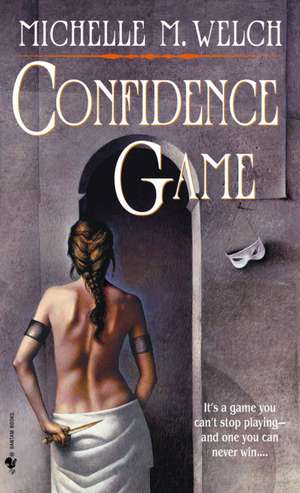

Confidence Game

Autor Michelle M. Welchen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2003

THEY BROKE HER.

Beneath its peaceful exterior, Dabion is a land of violence and intrigue, its politics run by judges, schemers, and spies. Elzith Kar is one such spy, gifted with an uncanny skill derived from rigorous training—and an unusual magic inherited from parents she never knew. Dabion may have use for her talent, but its rulers fear the magic that tempts it, so Elzith has hidden her history and true power, becoming a master player in a game she despises.

But now, as she heals in the aftermath of a dangerous mission, Elzith finds herself temporarily forced into life as a civilian. It is here she finds Tod Redtanner, a humble man with secrets of his own, and feels compelled to tell him her story. But as Elzith’s history unfolds and the present begins to unravel, it soon becomes clear that the past haunts more than just her dreams. And that if Elzith is to survive, she has no choice but to return to the world of intrigue and corruption that was once her domain. And this time she must play to win.

Preț: 54.13 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.36€ • 10.80$ • 8.61£

10.36€ • 10.80$ • 8.61£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553586275

ISBN-10: 0553586270

Pagini: 419

Dimensiuni: 107 x 174 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Ediția:Parental Adviso.

Editura: Spectra Books

ISBN-10: 0553586270

Pagini: 419

Dimensiuni: 107 x 174 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Ediția:Parental Adviso.

Editura: Spectra Books

Notă biografică

Michelle M. Welch is a fan of literature, music, libraries, Irish fiddling, history, Renaissance costumes, and dessert. She lives in Arizona with her cat and a room full of musical instruments.

Extras

1

Tod was going to be late. The woman's message said that she would come to see the flat precisely at noon. Keller didn't have a clock in his shop, but Tod was sure it was getting close to noon, and he still had to walk through Origh and two miles out of town to get to his cottage.

"It's all right Keller," he whispered to the older man, trying to hurry him along. "I'm sure they're fine, I'll take them now."

The printer looked up from the pages he was proofing, raising his face only a little bit, not relieving the weight that the low hang of his head put on his tired shoulders. He didn't say anything, but Tod heard his answer very clearly. Keller never cut corners on a job, even when he'd been swamped by three law revisions in one day, even when the Justices threatened him with shutting down his press if they didn't get their orders in rush time. Every page had to come out perfect, even if it meant that Keller didn't sleep. The printer was doing Tod's job and he was going to finish it. Tod would just have to wait.

Finally, Keller's dry voice uttered, "Good," and he gathered up the last of the barely dry sheets and filed them in a battered leather portfolio. "It's done, now get on your way. Although," Keller added, looking through his cracked window, "you'll have trouble hurrying anywhere."

Tod had been thinking the same thing as he paced anxiously past the window of the shop. Walking into Origh this morning, he'd seen troops of Public Force guards marching toward the center of town. Not that that was unusual--the pounding of their boots and the creak of the short heavy sticks and pistols swinging at their belts was something he heard every day he was in the city. When he'd first moved to the cottage on the outskirts he'd been shocked at how quiet it was without that sound. But there seemed to be more guards today than there usually were, and as Tod stood at Keller's window and waited for the printer to finish with his job, their numbers grew. Tod lost count of them; he didn't know there were so many in the whole District. Then they stopped moving and backed up in the street. Something was happening in the center of town and Tod's way was blocked.

"You there, back inside," a guard barked as Tod inched through the doorway. He startled and froze, but the guard was shouting at a clerk who'd stepped out of the chandler's shop next door. The clerk, his arms full of boxes of candles bound, no doubt, for some Justice's office, stepped up to the man in the gray uniform and began arguing. A moment later the chandler was out in the street, adding his booming voice to the argument, complaining about how this mess in the street was harming his business.

"Better run for it while you can, lad," Keller said at Tod's ear.

He only had a glance at what was going on as he darted out of Keller's door. The Public Force had filled up the street as far as Tod could see, preventing anyone from moving forward, pushing anyone who stepped out of their shops or houses back inside. Tod clutched his portfolio and hurried away in the opposite direction of the roadblock, and found himself in the middle of a thin crowd that was doing the same, escaping out of a bakery and away from the guards. From behind him, in the thick of the blockade, Tod thought he heard shouts and the distant sound of breaking glass.

For a second he stopped short. Breaking glass. Then it was himself he saw in the crowd, in the center of town. Shouts all around him, the press of bodies nearly sweeping him off his feet. Bricks were thrown, rocks hurled through windows, matches touched to whatever would burn. Where they had gotten the debris, Tod couldn't remember and couldn't imagine. He couldn't imagine because the streets of Origh were kept so clean, not to offend the Justices with the sight of waste. He couldn't remember because he had been drunk. He couldn't remember what the riot had been about--what had so angered the townspeople that they had scraped rocks from the ground to destroy whatever they could before the Public Force came--because he had been drunk. That was enough of a crime on its own, even without the rioting. Tod had no idea how he'd gotten out of it, but he had, and he'd ended up at home, free and frightened and sleepless and sober. Sober enough to dream.

That had been four years ago. He had no taste for gin now, almost. Only when he remembered the dreams. He clamped his eyes shut, hard, as if the face of his nightmare were in the street in front of him, and stumbled, his hand flung out for balance. Someone met his hand, grasped it, and steadied him. Then something was pressed into his hand, buried deep in his palm. That someone was gone before Tod opened his eyes.

Behind him shouts were cut short, dull cracks sounding on bone or flesh. In front of him those people who had gotten away were hurrying toward the edges of town. For a moment he stopped to look at the wad of paper in his hand. It was a note, scribbled hastily.

Follow Nanian, not the law.

Tod dropped the paper like it was a hot coal. Being found with it in his hands would be enough of a crime. Those were the rioters, then. Mystics, Nanianists. Tod had never heard of people like that outside of Cassile. Dabion wasn't a country for religion. He kicked the note into the gutter--a strangely dirty gutter--and started running.

Somehow he got out of Origh, onto the road home. When he was some distance away he finally felt it was safe to turn and look behind him. No gray uniforms had followed him out of town. He sighed with relief. Then he started thinking, confused, and looked behind him again. No one else was on the road, either. Where was his visitor? She must have been coming out of town, too. He started running again, hoping she hadn't beaten him home.

The little mechanical clock on the mantel read just a minute before noon when Tod rushed through his door. With a faint smile he dropped his package on his table, took a breath, and lowered himself into a chair. He would have time to rest, he thought as the clock's tinny bell began to ring. Then there was a rap at the door. Tod jumped wearily to his feet. She must have a watch, he thought. That was foolish, though. Only clerks had those things, officers in the Halls of Justice. His feet hurt from his long run and this irritated him so much that he forgot about wondering where his visitor had come from.

Tod opened the door. Elzith Kar stood outside. He regarded her for several moments, thinking she did not see him. She was looking away, her head dropped casually to the side as if surveying the herbs in his neighbor's box, and she said absolutely nothing to him. Any greeting Tod might have given seemed more and more ridiculous as time went by, and so he only looked at her in the silence. Clothed in the manner of Dabion's working class, she wore a loose blouse of a mute gray color, with a bodice laced over it to fit a slight figure. Wealthier women now wore their bodices inside their dresses--so Tod had heard--and had servants stitch the gown to the undergarment each morning. Elzith Kar was a washerwoman, perhaps, but she seemed too thin to haul loads of washing. Was she a lady's maid, forever stitching her mistress into her clothing? Then Tod continued his inventory and halted. The woman before him wore breeches. Stranger still, the breeches ended not at white stockings like his (though his were rather yellow) but at boots, blackened leather pulled up to her knees. Boots like those worn in Mandera, the seaside country to the south, or by the guards of the Public Force--

"Your neighbor's a thief," Elzith said suddenly.

Tod opened his mouth but not even a ridiculous greeting could come out this time.

The woman was regarding him now. "Has he ever stolen from you?" Her voice was even and clear, her words sharp at the edges. She spoke in a command, though quietly enough that no one beyond his doorway would hear her. It was like the voice of a Justice, but no women worked in the Great Halls.

She was watching him still. Tod felt himself flush; he had not yet answered. "No," he gasped. Elzith's eyes were green, steady, leveled on him in examination. Then, suddenly, she nodded. "Good," she said, only half to him, a motion of dismissal, and then, "Shall I see the flat now?"

The flat was the lower floor of Tod's cottage, half-buried in a hill. Here outside the city the land was filled with smooth rolling hills and valleys, blanketed with rich velvety grass. It was beautiful land, peaceful, and almost empty. The cities of Dabion were scattered, built around the branches of the Great Halls of Justice that were posted throughout the country: Insigh, Tanasigh, Kerr, Origh two miles away, and others. Almost all the remaining population had been ousted from the country generations before, leaving the hills and valleys nearly barren. The few commoners who remained lived in cottages half-buried in the slopes like the burrows of moles.

Tod stumbled a little as he started down the steps that edged the slope of the hill, rough-hewn shards of flagstone placed irregularly in the earth. Tod's cottage was one of a row of three burrowed into this hill. All three had lower floors with doors that let out at the bottom of the slope. The inner stairwell that accessed the lower floor in Tod's cottage had been blocked to form a separate flat. The neighbors did not use the outside steps; Widow Carther's lower door, at the far end of the row, was even boarded over.

"These steps need fixing," Tod said, his voice tripping, still a little breathless from his frantic rush out of town. "I'm afraid they were let go for a long time--I just started trying to fix them up a few years ago. I try to keep them clean, but the rain, you know, and mud, and then in the winter they get icy, then snow covers them up, and once it melts in the spring . . ." Tod cut himself short. The riot, the note, they had made him lose his wits, and he was babbling like a fool. He usually only spoke much in the company of someone quieter than himself, and his great-aunt had been the last person to fit that description.

No taste for gin except when he remembered the dreams, his great-aunt's ghost face in them. He almost lost his footing completely. It was too much to remember in one day. He swallowed hard and looked around, searching for something else to see. Behind him Elzith was navigating the steps, not stumbling at all.

"I need to replace the stones, at any rate," Tod said thickly. "It's so hard to contact the landlord, though. He's a Lesser Justice, of course."

Tod did not expect his companion to finish his thought. "Of course," said Elzith dryly, surprising him. "And what do they care for us?"

Tod's hand shook and rattled the keys in the lock. Speaking ill of the Justices was enough of a crime. He had a mad, sick sensation that the woman's voice was carrying over the fields, where the guards massed in the streets of Origh would hear it and come for her. For a second he was also sure that she knew exactly what had happened in the middle of town. He fumbled the door open and rushed Elzith inside.

The basement flat was tiny, cold, low-ceilinged. Morrn, Tod's former renter of six years, hadn't cared. Morrn had been perfectly happy with the flat, until he'd been carried off to the Great Hall for keeping a distillery there. Three years later, the smell of gin was almost out of the floorboards and plastered walls. The renter Tod had had during those three years since Morrn left hadn't seemed to mind, either, but that man had been a Healer. Healers were a race so strange, so mysterious, that Tod could say little about his previous flatmate at all.

In the flat now was another mystery. Elzith made a circuit of the room in a few strides, peering at the walls, checking the skinny mattress for fleas. She spent more time at the chest, opening its drawers and looking inside them. Tod's imagination tried a string of explanations for her strange actions, then gave up. Abruptly Elzith straightened, fixing him with that gaze that weighed him like a balance. "Is it available today?" she asked.

Tod floundered.

"You have no other inquiries?" Elzith restated.

Tod shook his head. "No. You could move in right now."

"Good," she answered, nodding as if she had known already. She drew a fold of notes from a pocket in the breeches, confirmed the flat's price, and paid Tod for a full season. He failed to find another single word. "The key," Elzith prompted him after waiting silently for a moment.

"Yes," mumbled Tod, fussing it off his ring. "But your things--"

"My things," the woman said. She ushered Tod out of the flat that was now hers and locked its door. "I will have to get some." Then she climbed the irregular steps up the slope and vanished behind the green rise of the hill.

Tod was going to be late. The woman's message said that she would come to see the flat precisely at noon. Keller didn't have a clock in his shop, but Tod was sure it was getting close to noon, and he still had to walk through Origh and two miles out of town to get to his cottage.

"It's all right Keller," he whispered to the older man, trying to hurry him along. "I'm sure they're fine, I'll take them now."

The printer looked up from the pages he was proofing, raising his face only a little bit, not relieving the weight that the low hang of his head put on his tired shoulders. He didn't say anything, but Tod heard his answer very clearly. Keller never cut corners on a job, even when he'd been swamped by three law revisions in one day, even when the Justices threatened him with shutting down his press if they didn't get their orders in rush time. Every page had to come out perfect, even if it meant that Keller didn't sleep. The printer was doing Tod's job and he was going to finish it. Tod would just have to wait.

Finally, Keller's dry voice uttered, "Good," and he gathered up the last of the barely dry sheets and filed them in a battered leather portfolio. "It's done, now get on your way. Although," Keller added, looking through his cracked window, "you'll have trouble hurrying anywhere."

Tod had been thinking the same thing as he paced anxiously past the window of the shop. Walking into Origh this morning, he'd seen troops of Public Force guards marching toward the center of town. Not that that was unusual--the pounding of their boots and the creak of the short heavy sticks and pistols swinging at their belts was something he heard every day he was in the city. When he'd first moved to the cottage on the outskirts he'd been shocked at how quiet it was without that sound. But there seemed to be more guards today than there usually were, and as Tod stood at Keller's window and waited for the printer to finish with his job, their numbers grew. Tod lost count of them; he didn't know there were so many in the whole District. Then they stopped moving and backed up in the street. Something was happening in the center of town and Tod's way was blocked.

"You there, back inside," a guard barked as Tod inched through the doorway. He startled and froze, but the guard was shouting at a clerk who'd stepped out of the chandler's shop next door. The clerk, his arms full of boxes of candles bound, no doubt, for some Justice's office, stepped up to the man in the gray uniform and began arguing. A moment later the chandler was out in the street, adding his booming voice to the argument, complaining about how this mess in the street was harming his business.

"Better run for it while you can, lad," Keller said at Tod's ear.

He only had a glance at what was going on as he darted out of Keller's door. The Public Force had filled up the street as far as Tod could see, preventing anyone from moving forward, pushing anyone who stepped out of their shops or houses back inside. Tod clutched his portfolio and hurried away in the opposite direction of the roadblock, and found himself in the middle of a thin crowd that was doing the same, escaping out of a bakery and away from the guards. From behind him, in the thick of the blockade, Tod thought he heard shouts and the distant sound of breaking glass.

For a second he stopped short. Breaking glass. Then it was himself he saw in the crowd, in the center of town. Shouts all around him, the press of bodies nearly sweeping him off his feet. Bricks were thrown, rocks hurled through windows, matches touched to whatever would burn. Where they had gotten the debris, Tod couldn't remember and couldn't imagine. He couldn't imagine because the streets of Origh were kept so clean, not to offend the Justices with the sight of waste. He couldn't remember because he had been drunk. He couldn't remember what the riot had been about--what had so angered the townspeople that they had scraped rocks from the ground to destroy whatever they could before the Public Force came--because he had been drunk. That was enough of a crime on its own, even without the rioting. Tod had no idea how he'd gotten out of it, but he had, and he'd ended up at home, free and frightened and sleepless and sober. Sober enough to dream.

That had been four years ago. He had no taste for gin now, almost. Only when he remembered the dreams. He clamped his eyes shut, hard, as if the face of his nightmare were in the street in front of him, and stumbled, his hand flung out for balance. Someone met his hand, grasped it, and steadied him. Then something was pressed into his hand, buried deep in his palm. That someone was gone before Tod opened his eyes.

Behind him shouts were cut short, dull cracks sounding on bone or flesh. In front of him those people who had gotten away were hurrying toward the edges of town. For a moment he stopped to look at the wad of paper in his hand. It was a note, scribbled hastily.

Follow Nanian, not the law.

Tod dropped the paper like it was a hot coal. Being found with it in his hands would be enough of a crime. Those were the rioters, then. Mystics, Nanianists. Tod had never heard of people like that outside of Cassile. Dabion wasn't a country for religion. He kicked the note into the gutter--a strangely dirty gutter--and started running.

Somehow he got out of Origh, onto the road home. When he was some distance away he finally felt it was safe to turn and look behind him. No gray uniforms had followed him out of town. He sighed with relief. Then he started thinking, confused, and looked behind him again. No one else was on the road, either. Where was his visitor? She must have been coming out of town, too. He started running again, hoping she hadn't beaten him home.

The little mechanical clock on the mantel read just a minute before noon when Tod rushed through his door. With a faint smile he dropped his package on his table, took a breath, and lowered himself into a chair. He would have time to rest, he thought as the clock's tinny bell began to ring. Then there was a rap at the door. Tod jumped wearily to his feet. She must have a watch, he thought. That was foolish, though. Only clerks had those things, officers in the Halls of Justice. His feet hurt from his long run and this irritated him so much that he forgot about wondering where his visitor had come from.

Tod opened the door. Elzith Kar stood outside. He regarded her for several moments, thinking she did not see him. She was looking away, her head dropped casually to the side as if surveying the herbs in his neighbor's box, and she said absolutely nothing to him. Any greeting Tod might have given seemed more and more ridiculous as time went by, and so he only looked at her in the silence. Clothed in the manner of Dabion's working class, she wore a loose blouse of a mute gray color, with a bodice laced over it to fit a slight figure. Wealthier women now wore their bodices inside their dresses--so Tod had heard--and had servants stitch the gown to the undergarment each morning. Elzith Kar was a washerwoman, perhaps, but she seemed too thin to haul loads of washing. Was she a lady's maid, forever stitching her mistress into her clothing? Then Tod continued his inventory and halted. The woman before him wore breeches. Stranger still, the breeches ended not at white stockings like his (though his were rather yellow) but at boots, blackened leather pulled up to her knees. Boots like those worn in Mandera, the seaside country to the south, or by the guards of the Public Force--

"Your neighbor's a thief," Elzith said suddenly.

Tod opened his mouth but not even a ridiculous greeting could come out this time.

The woman was regarding him now. "Has he ever stolen from you?" Her voice was even and clear, her words sharp at the edges. She spoke in a command, though quietly enough that no one beyond his doorway would hear her. It was like the voice of a Justice, but no women worked in the Great Halls.

She was watching him still. Tod felt himself flush; he had not yet answered. "No," he gasped. Elzith's eyes were green, steady, leveled on him in examination. Then, suddenly, she nodded. "Good," she said, only half to him, a motion of dismissal, and then, "Shall I see the flat now?"

The flat was the lower floor of Tod's cottage, half-buried in a hill. Here outside the city the land was filled with smooth rolling hills and valleys, blanketed with rich velvety grass. It was beautiful land, peaceful, and almost empty. The cities of Dabion were scattered, built around the branches of the Great Halls of Justice that were posted throughout the country: Insigh, Tanasigh, Kerr, Origh two miles away, and others. Almost all the remaining population had been ousted from the country generations before, leaving the hills and valleys nearly barren. The few commoners who remained lived in cottages half-buried in the slopes like the burrows of moles.

Tod stumbled a little as he started down the steps that edged the slope of the hill, rough-hewn shards of flagstone placed irregularly in the earth. Tod's cottage was one of a row of three burrowed into this hill. All three had lower floors with doors that let out at the bottom of the slope. The inner stairwell that accessed the lower floor in Tod's cottage had been blocked to form a separate flat. The neighbors did not use the outside steps; Widow Carther's lower door, at the far end of the row, was even boarded over.

"These steps need fixing," Tod said, his voice tripping, still a little breathless from his frantic rush out of town. "I'm afraid they were let go for a long time--I just started trying to fix them up a few years ago. I try to keep them clean, but the rain, you know, and mud, and then in the winter they get icy, then snow covers them up, and once it melts in the spring . . ." Tod cut himself short. The riot, the note, they had made him lose his wits, and he was babbling like a fool. He usually only spoke much in the company of someone quieter than himself, and his great-aunt had been the last person to fit that description.

No taste for gin except when he remembered the dreams, his great-aunt's ghost face in them. He almost lost his footing completely. It was too much to remember in one day. He swallowed hard and looked around, searching for something else to see. Behind him Elzith was navigating the steps, not stumbling at all.

"I need to replace the stones, at any rate," Tod said thickly. "It's so hard to contact the landlord, though. He's a Lesser Justice, of course."

Tod did not expect his companion to finish his thought. "Of course," said Elzith dryly, surprising him. "And what do they care for us?"

Tod's hand shook and rattled the keys in the lock. Speaking ill of the Justices was enough of a crime. He had a mad, sick sensation that the woman's voice was carrying over the fields, where the guards massed in the streets of Origh would hear it and come for her. For a second he was also sure that she knew exactly what had happened in the middle of town. He fumbled the door open and rushed Elzith inside.

The basement flat was tiny, cold, low-ceilinged. Morrn, Tod's former renter of six years, hadn't cared. Morrn had been perfectly happy with the flat, until he'd been carried off to the Great Hall for keeping a distillery there. Three years later, the smell of gin was almost out of the floorboards and plastered walls. The renter Tod had had during those three years since Morrn left hadn't seemed to mind, either, but that man had been a Healer. Healers were a race so strange, so mysterious, that Tod could say little about his previous flatmate at all.

In the flat now was another mystery. Elzith made a circuit of the room in a few strides, peering at the walls, checking the skinny mattress for fleas. She spent more time at the chest, opening its drawers and looking inside them. Tod's imagination tried a string of explanations for her strange actions, then gave up. Abruptly Elzith straightened, fixing him with that gaze that weighed him like a balance. "Is it available today?" she asked.

Tod floundered.

"You have no other inquiries?" Elzith restated.

Tod shook his head. "No. You could move in right now."

"Good," she answered, nodding as if she had known already. She drew a fold of notes from a pocket in the breeches, confirmed the flat's price, and paid Tod for a full season. He failed to find another single word. "The key," Elzith prompted him after waiting silently for a moment.

"Yes," mumbled Tod, fussing it off his ring. "But your things--"

"My things," the woman said. She ushered Tod out of the flat that was now hers and locked its door. "I will have to get some." Then she climbed the irregular steps up the slope and vanished behind the green rise of the hill.

Descriere

This thrilling debut novel introduces former spy Elzith Kar, discarded by her government and left to live a new life, who must now use her magic to return to a world of intrigue and corruption. Original.