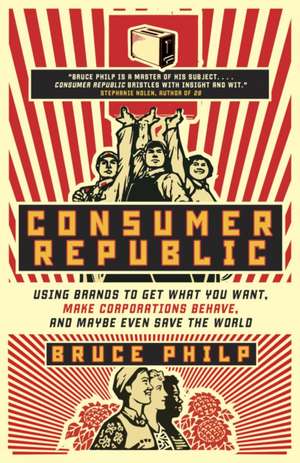

Consumer Republic: Using Brands to Get What You Want, Make Corporations Behave, and Maybe Even Save the World

Autor Bruce Philpen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2012

The foundation of Consumer Republic's message is this single, inarguable truth: Brands make corporations accountable. Expensive to create, essential to making money, and more public than anything else a corporation has or does, a brand is an enormously valuable and fragile asset to them. Through this book Bruce Philp will inspire you to buy less, maybe, but demand better; to make better choices; and then to speak up when you're happy and when you're not. Pin every one of these acts to a brand and corporations will be forced to cooperate in making our way of life sustainable. Ultimately, if we take control of brands, we can save the world.

Preț: 97.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 146

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.66€ • 20.35$ • 15.73£

18.66€ • 20.35$ • 15.73£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771070044

ISBN-10: 0771070047

Pagini: 274

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771070047

Pagini: 274

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

BRUCE PHILP spent nearly three decades in the business of advertising and branding, mediating between corporations who want to make money and consumers who hope to exchange some for a better life. Working with some of the world's most famous brands, he has been in a unique position to observe how marketers and their consumers operate as two solitudes, and the dysfunction, waste, and damage that often result. In 2008, he co-authored the national bestseller The Orange Code: How ING Direct Succeeded By Being A Rebel With a Cause. Bruce Philp speaks and writes on branding at his blog, Brand Cowboy, and is an occasional contributor to newspaper and marketing trade journals.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

I have a dream. In this dream, I have purchased a toaster. I’m quite excited about this toaster. It wasn’t cheap, but then it is an Acme. Acme is a brand with real toaster cred. My new appliance is lovely to look at, built like a bank vault, and it apparently does a stellar job of browning bagels, which are my favourite breakfast food. I know this, because I have done my homework. Most of the people who have purchased the same brand of toaster are very pleased with this feature, and they’ve said so on the Google-powered brand-rating website that I always consult about such things. Let’s call it consumerrepublic.com. I trust it because so many people contribute ratings to its brand trust indices, and because Google cleverly assigns authority to each rater and weights his or her opinions using one of its brilliant algorithm thingies. Thus, if this Internet resource tells me that Acme is a brilliant maker of toasters and that their products will reflect their owners’ good taste and judgment, I’m inclined to believe it.

Except that mine is broken. Right out of the box. I’m a bit sad about this, because I’m not one to go out and buy a new toaster every five minutes. Or a new anything, for that matter. I, along with the rest of the world in my dream, prefer to buy things only when I need them, or when I’m genuinely inspired by them. I generally pay for them in cash, so that these things are really mine, rather than things I’m pretending are mine. That makes shopping for something like a toaster a bit of an event, and much more fun. It also means that I expect a lot when I plunk down my hard-earned money. When I bring a new purchase home to my modest, paid-for, tasteful residence, furnished only with objects that are useful and/or inspiring, I look forward to the unveiling. In this case, however, that shining moment, and the beginning of many years of mornings made sunnier by bagel perfection, must be postponed.

With a mildly exasperated sigh, I sit down at my computer. First, I go back to consumerrepublic.com, the brand-rating website that steered me to Acme, sign on, and add my purchase to the “pending resolution” file. On this imaginary website, every brand has one. It allows people in my situation to let the world know that there is a problem but that the jury is still out as to how that brand will deal with it. The site aggregates these complaints, and lists the information alongside its brand trust ratings. Brand marketers pay close attention to this leading indicator the way they used to watch the Dow, because this site doesn’t just score brands for trust and performance – it also trends that score. When I looked at Acme’s ratings while shopping for my dream toaster, I could see not only that they were pretty high but also that they had been gently trending higher for a long time. This company seemed not only to be good; it seemed to be getting better. Acme won’t want to risk reversing that trend. Indeed, somewhere at Acme Global Headquarters, the potentially negative experience I’m having has already RSSed its way to a real-time customer satisfaction database. It may even have made a little bong noise when it got there. That would be cool. Regardless, Acme is already paying attention. Brand trust is too hard and expensive to earn to risk it on one broken toaster.

My next task is to contact Acme directly, which I do through their corporate website. Their site notices that I’ve come from consumerrepublic.com, so it jumps me up in the queue for a response. It doesn’t take long, then, before Acme offers me two options on the spot. I can return the toaster for a replacement, or I can have it repaired. Being a guy who hates to see anything go to waste, I pick the second. In my dream, you can get things fixed. People are making their things last longer, and repair shops have made a big comeback. Noting my IP address, Acme geolocates me and is able to recommend a shop a few minutes away. The whole process so far has taken under ten minutes. I pack the toaster back into its reusable box and head for Main Street.

By the time I get to the shop, Acme has already sent an electronic docket to the repairperson. In this dream, he’s a cranky but basically kind older fellow, a bit like Mr. Hooper on Sesame Street. The problem turns out to be simple to resolve. Mr. Hooper notices a screw that’s loose and binding the mechanism. He fixes it on the spot, makes some trenchant remarks about the weather, and I’m on my way. Mr. Hooper closes the electronic docket, alerting Acme that the technical issue, at least, has been resolved. Acme, however, is not breathing easy just yet. In my dream world, their brand isn’t off the hook until I say it is.

So, just to make them sweat, I take my time walking home. I wave as I pass all the other modest, tasteful, paid-for residences in my neighbourhood, stopping to talk to my next-door neighbour, who is enjoying the sunny morning by waxing his immaculately maintained ten-year-old car. It looks and runs like new, and people in the neighbourhood admire him for this. Finally home, I place the toaster on the kitchen counter and pop in a bagel. Moments later, golden brown perfection. Flushed with carbohydrate-induced bliss and feeling benevolent, I jump back on the web and remove my “pending resolution” flag at consumerrepublic.com. For good measure, I even head over to YouTube and tag Acme’s latest commercial as “basically true” or “essentially credible.” Something like that. A great rating from me on consumerrepublic.com will have to wait, though. It takes more than one perfect bagel to win me over.

So that’s my dream. A world in which we live a little more simply, we buy things that are better rather than cheaper and more numerous, and we make them last. Where brands survive on selling better, fewer products, and fear letting us down more than they ever fear a decline in their stock price. And where the bagels are delicious.

That would really be cool.

I started work on Consumer Republic at what I hope will turn out to have been the lowest point in the history of consumerism. As I write, the civilized world is struggling to emerge from an economic near-disaster. This calamity’s very roots, they tell us, lie in consumer debt and Wall Street’s cynical exploitation of it. And this calamity has only momentarily distracted our attention from an even bigger mess, a planet in unprecedented distress from being plundered to meet the insatiable demands of its human inhabitants. More and more of us need and want more things, so we’re ravaging the place like raccoons at a dumpster. More and more of us have been unwilling to wait until we can afford all that stuff, so we’ve mortgaged our futures like Wimpy hitting up Popeye for hamburger money. On CNN, serious-looking people in suits offer a glum play-by-play of the nasty comeuppance in financial markets, while a few channels up the dial at National Geographic, freaked-out-looking people in khaki shorts, predict the same for our environment. It’s all a bit scary and, although nobody is putting it in exactly these words, it seems clear to me that the fundamental problem is too many people being sold too much stuff. Marketing, therefore, might essentially be at the bottom of all this.

It didn’t take everybody else long to arrive at the same conclusion. A Harris Interactive poll from the spring of 2009, when things seemed economically at their worst, showed that two thirds of Americans had already decided Madison Avenue was at least part of the problem. Half of those polled believed that most of the blame could be sent to that address.

It was a natural enough reaction. Marketing is an easy, logical scapegoat, if the problem is too much consumption. But, to me, this doesn’t quite add up.

Most people understand that marketing has something to do with profitably meeting the demands of a group of people for a particular product or service. A marketer’s job is to find a socalled “need,” and then find a way to meet it and make some money in the process. To a marketer, consumer demand is assumed. It’s like a natural resource to be exploited. It’s just out there, like air. The marketer simply has to know how to recognize it, and then cater to it. However, if you think about it, there is a big, fat, and possibly baseless assumption behind that definition: that every sale of a product or service is self-validating. In other words, a marketer’s responsibility ends when the money changes hands. If you bought it, it’s because you needed it.

Yet if it’s as simple as that, how can we explain this orgy of debt-fuelled consumption in the last decade or so? Surely these “needs” of ours haven’t increased over time, have they? On the contrary, for a lot of us in the so-called developed world, they’ve diminished quite a bit. A couple of centuries ago, I could have presented a persuasive list of “needs” to anyone who cared to cater to them, from nutrition and personal hygiene to transportation and telecommunication. But now? I don’t know about you, but I’m kind of running out of really pressing problems that could be solved with a trip to the mall. When fortunes can be made by combining tooth-whitening agents with mouthwash, or by devising a way for your car to recognize your mobile phone so that you can have conversations through the stereo, marketers have got to be scraping the bottom of the needs barrel.

To me, this is a paradox. If marketing is about needs, and we need less today than we ever have, why is there more marketing? More perplexing still, why does it seem to be working? Working so well, in fact, that it risks destroying our way of life? Either marketing never was about needs in the first place, or none of us understood what a need really was.

Well, almost none of us. Most people with a passing interest in psychology have at some point run into the work of Abraham Maslow. His Hierarchy of Needs is a staple theory of the science, and it’s been sticky and viral because of its intuitive and simple logic: We humans will focus our attention on meeting needs in a predictable sequence, and that sequence will put matters of survival first and self-actualization last. In other words, nobody is going to give much thought to his personal value system or his inner child if he’s hungry and cold. Conversely, if a person is relatively safe, warm, and well fed, and enjoys the support of a social system, she will have time to spend on the bigger questions of morality and her purpose in the world. These then become her “needs.” This logic presents two interesting implications for what marketing really is: First, it says that our definition of “needs” is fluid and contextual. Second, it says that what motivates the way we meet our needs evolves inevitably from being a matter of survival – I’m hungry – to something more to do with self-expression – This is who I am.

Maslow proposed his hierarchy as a way of explaining individual human behaviour. But can it explain the behaviour of societies, too? Do we collectively move in a way that mirrors our individual behaviours? I think, more often than not, we do. When you look at our collective hierarchy of needs, it would be hard to dispute that, as a group, we’ve worked our way considerably up the ladder over the past century, and that many of us are fortunate enough to have our basic needs consistently met. When an entire community has its basic needs met, it will inevitably tend to turn its attention to values, and to the pursuit of self-esteem, achievement, and enlightenment. Without fear, societies evolve more freely. It’s our collective aspiration. As if to underscore the point, it seems like only yesterday that the United States inaugurated a president whose election campaign made a point of speaking more loudly to our better selves than it did to our fear of real or imagined threats to our survival. Based on the world’s reaction back on that giddy November 4, 2008, election night, humanity seemed ready to ascend, ready to dedicate ourselves to being better rather than just being safe. Collective self-actualization was nigh. We were buying it big time.

Yet a little more than three weeks after that night, on November 29, 2008 – Black Friday, so named because it’s the time of year when American retailers are said to cross the line between losing and making money, and the official start of the holiday shopping season – a temporary worker at the Walmart at Green Acres Mall in Valley Stream, New York, was trampled to death by a mob of shoppers. They had been gathering in front of the store since the previous day, champing at the bit to take advantage of bargains. The local police had deployed crowd control officers as early as 3:30 a.m., and by 5:00 a.m., according to a New York Times reporter, “The crowd of more than 2,000 had become a rabble and could be held back no longer.” A rabble? At Walmart? It was an unusually dramatic expression of the mania of consumerism, with a tragic and thankfully rare result. But its symbolic power is undeniable: Here, on the pivotal day of the year when retailers were finally moving into the black, they seemed to be depending on humanity’s worst urges to do it. The scene, according to an investigating police officer, was “utter chaos,” and the crowd “out of control.” And the lure was not sustenance or shelter or escape from predators, but video games, paper towels, power tools, and fleece wear. We were still buying those, too.

Again, this just doesn’t make sense. Something is broken, here. On the one hand, we have those opportunistic marketers: Believing that their role in the world is to relieve us of our money by meeting our “needs,” they sell us everything as though our lives depended on buying it. Their default tool is urgency. Urgency to whiten and deodorize, to seem more prosperous than our neighbours, to pay less than those same neighbours in the process, to act now before it’s all gone. High-definition televisions are being brought to market as urgently as if they were bags of rice thrown to the starving from the backs of Red Cross trucks. On the other hand, scrambling after them are we, the consumers. Made fools of once too often, egged on by pundits, too vain to acknowledge our own vanity, we behave as if consumption were a competitive sport in which whoever gets the most for the least wins. Which is surely not the path to self actualization, or any other legitimate need for that matter. We and the marketers who sell to us have locked ourselves into a kind of destructive codependency. Is it any wonder we’re all in debt? Is it any wonder that vast economies are erupting in far-flung corners of the planet premised solely on the making of more things for less money? Is it any wonder that the planet is groaning under the strain?

No, it is not. What’s amazing, in fact, is that things aren’t worse than they are.

I don’t think I’m alone in observing this, either. I think people are beginning to feel a sense of culpability. I’ve lived through a few Main Street recessions, but never one that raised the questions that this one has about the morality of consuming: about how much is enough; about the social meaning of material things, or whether the things we buy should have any social meaning at all; about personal accountability. We aren’t necessarily saying so out loud, but we know we had a hand in this.

Still, if history teaches us nothing else, it certainly teaches us that humans won’t bear the weight of repentance for long. We don’t like hair shirts, even if they are on sale. We are built to be hopeful. So, in the next short while, two things will inevitably happen. First, people will look for someone that history can blame for this so they can get on with their lives. And second, people will return to some modified version of their natural state, which, here in the “developed world,” means consuming. What worries me is, we really will blame branded marketing. When the dust has settled and everyone feels we’ve flagellated ourselves enough, we’re going to decide once and for all that corporations and their evil organ grinder’s monkeys, brands, have been the problem.

But before we toss the bathwater of marketing out the window, let’s make sure we see the brand baby for what it is, and for what it could be. So what is it?

Imagine that you have a headache.

Unable to stand it any more, you make for the nearest drug store and face the shelf where they keep the pain relievers. If you are like roughly a third of North Americans, you will reach for Tylenol. Why? Right next to it, there is a generic product that is identical — I mean identical — in its formulation. It contains 325 mg of acetaminophen per tablet, just like regular Tylenol. It is dollars cheaper, pharmacologically the same, and, by statute, therapeutically equivalent. Why on earth are you paying more? Are you a fool?

No, you are not. Whether or not you’re willing to admit it, that extra couple of dollars is buying you two kinds of insurance: One, that you can delegate to Johnson & Johnson the task of solving your headache rather than having to learn the pharmacology of acetaminophen for yourself. And, two, that if something goes wrong, someone will take responsibility.

One day, in 1982, something did go wrong. A murderer tampered with Tylenol on the shelves of a Chicago drug store, and killed seven people. Johnson & Johnson’s response became a case study in public relations. From their unprecedented transparency with the press, to their willingness to destroy millions of dollars’ worth of product as a precaution, to their rapid and brilliant innovation of security features, they did everything right and quickly. Their market share fell to 7 per cent from 37 per cent in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, but it rebounded to 30 per cent within twelve months of the incident. They remain today the most trusted analgesic brand in the market.

When this happened, the corporation that makes Tylenol did more than they had to do. Even allowing for some margin of human decency, there is an important practical reason why Johnson & Johnson took responsibility so completely and so vigorously: their brand. The fame of the Tylenol name made their response to the crisis public. Consumers became a jury, and this was Tylenol’s trial of a lifetime.

That’s why we pay more than we need to for a lot of the products we buy. That’s why brands matter to us, however secretly or unconsciously. Because they make corporations accountable, and in doing that they give us power.

In Consumer Republic, I want to do three things:

First, I want to convince you that you have this power. I’m going to give you a glimpse behind the curtain of marketing and show you the role that we as consumers really play in that process.

Then, I’m going to offer a different, more contemporary, and relevant way to look at the role that brands and consumption play in our lives. I want to convince you that we need to bury the idea of status, right now, and that something much healthier and more interesting is already starting to replace it. In doing this, I hope to convince you that making brands work for us is much more satisfying and productive than pretending they don’t matter.

Finally, I want to get you excited about why this is our moment. We’re warned constantly that we should expect less from the future than we became accustomed to in the past. I think that means we should also expect better, and I think we finally have in our hands the means to say so and the power to back it up. Commerce has come a long way from the time when the only indication of the health of a marketer’s business was whether the merchandise was moving or not. Now, they can see and hear trouble coming before it gets there. Now, as never before, marketers can be influenced to do what we want them to do, as a condition of remaining in business.

Consumer Republic isn’t about guilt and doom. It’s about possibility. This moment in our history, with its crisis and its empowering social and technological changes, has finally given consumers the genuine autonomy we were meant to have all along. This book is about what to do with it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Except that mine is broken. Right out of the box. I’m a bit sad about this, because I’m not one to go out and buy a new toaster every five minutes. Or a new anything, for that matter. I, along with the rest of the world in my dream, prefer to buy things only when I need them, or when I’m genuinely inspired by them. I generally pay for them in cash, so that these things are really mine, rather than things I’m pretending are mine. That makes shopping for something like a toaster a bit of an event, and much more fun. It also means that I expect a lot when I plunk down my hard-earned money. When I bring a new purchase home to my modest, paid-for, tasteful residence, furnished only with objects that are useful and/or inspiring, I look forward to the unveiling. In this case, however, that shining moment, and the beginning of many years of mornings made sunnier by bagel perfection, must be postponed.

With a mildly exasperated sigh, I sit down at my computer. First, I go back to consumerrepublic.com, the brand-rating website that steered me to Acme, sign on, and add my purchase to the “pending resolution” file. On this imaginary website, every brand has one. It allows people in my situation to let the world know that there is a problem but that the jury is still out as to how that brand will deal with it. The site aggregates these complaints, and lists the information alongside its brand trust ratings. Brand marketers pay close attention to this leading indicator the way they used to watch the Dow, because this site doesn’t just score brands for trust and performance – it also trends that score. When I looked at Acme’s ratings while shopping for my dream toaster, I could see not only that they were pretty high but also that they had been gently trending higher for a long time. This company seemed not only to be good; it seemed to be getting better. Acme won’t want to risk reversing that trend. Indeed, somewhere at Acme Global Headquarters, the potentially negative experience I’m having has already RSSed its way to a real-time customer satisfaction database. It may even have made a little bong noise when it got there. That would be cool. Regardless, Acme is already paying attention. Brand trust is too hard and expensive to earn to risk it on one broken toaster.

My next task is to contact Acme directly, which I do through their corporate website. Their site notices that I’ve come from consumerrepublic.com, so it jumps me up in the queue for a response. It doesn’t take long, then, before Acme offers me two options on the spot. I can return the toaster for a replacement, or I can have it repaired. Being a guy who hates to see anything go to waste, I pick the second. In my dream, you can get things fixed. People are making their things last longer, and repair shops have made a big comeback. Noting my IP address, Acme geolocates me and is able to recommend a shop a few minutes away. The whole process so far has taken under ten minutes. I pack the toaster back into its reusable box and head for Main Street.

By the time I get to the shop, Acme has already sent an electronic docket to the repairperson. In this dream, he’s a cranky but basically kind older fellow, a bit like Mr. Hooper on Sesame Street. The problem turns out to be simple to resolve. Mr. Hooper notices a screw that’s loose and binding the mechanism. He fixes it on the spot, makes some trenchant remarks about the weather, and I’m on my way. Mr. Hooper closes the electronic docket, alerting Acme that the technical issue, at least, has been resolved. Acme, however, is not breathing easy just yet. In my dream world, their brand isn’t off the hook until I say it is.

So, just to make them sweat, I take my time walking home. I wave as I pass all the other modest, tasteful, paid-for residences in my neighbourhood, stopping to talk to my next-door neighbour, who is enjoying the sunny morning by waxing his immaculately maintained ten-year-old car. It looks and runs like new, and people in the neighbourhood admire him for this. Finally home, I place the toaster on the kitchen counter and pop in a bagel. Moments later, golden brown perfection. Flushed with carbohydrate-induced bliss and feeling benevolent, I jump back on the web and remove my “pending resolution” flag at consumerrepublic.com. For good measure, I even head over to YouTube and tag Acme’s latest commercial as “basically true” or “essentially credible.” Something like that. A great rating from me on consumerrepublic.com will have to wait, though. It takes more than one perfect bagel to win me over.

So that’s my dream. A world in which we live a little more simply, we buy things that are better rather than cheaper and more numerous, and we make them last. Where brands survive on selling better, fewer products, and fear letting us down more than they ever fear a decline in their stock price. And where the bagels are delicious.

That would really be cool.

I started work on Consumer Republic at what I hope will turn out to have been the lowest point in the history of consumerism. As I write, the civilized world is struggling to emerge from an economic near-disaster. This calamity’s very roots, they tell us, lie in consumer debt and Wall Street’s cynical exploitation of it. And this calamity has only momentarily distracted our attention from an even bigger mess, a planet in unprecedented distress from being plundered to meet the insatiable demands of its human inhabitants. More and more of us need and want more things, so we’re ravaging the place like raccoons at a dumpster. More and more of us have been unwilling to wait until we can afford all that stuff, so we’ve mortgaged our futures like Wimpy hitting up Popeye for hamburger money. On CNN, serious-looking people in suits offer a glum play-by-play of the nasty comeuppance in financial markets, while a few channels up the dial at National Geographic, freaked-out-looking people in khaki shorts, predict the same for our environment. It’s all a bit scary and, although nobody is putting it in exactly these words, it seems clear to me that the fundamental problem is too many people being sold too much stuff. Marketing, therefore, might essentially be at the bottom of all this.

It didn’t take everybody else long to arrive at the same conclusion. A Harris Interactive poll from the spring of 2009, when things seemed economically at their worst, showed that two thirds of Americans had already decided Madison Avenue was at least part of the problem. Half of those polled believed that most of the blame could be sent to that address.

It was a natural enough reaction. Marketing is an easy, logical scapegoat, if the problem is too much consumption. But, to me, this doesn’t quite add up.

Most people understand that marketing has something to do with profitably meeting the demands of a group of people for a particular product or service. A marketer’s job is to find a socalled “need,” and then find a way to meet it and make some money in the process. To a marketer, consumer demand is assumed. It’s like a natural resource to be exploited. It’s just out there, like air. The marketer simply has to know how to recognize it, and then cater to it. However, if you think about it, there is a big, fat, and possibly baseless assumption behind that definition: that every sale of a product or service is self-validating. In other words, a marketer’s responsibility ends when the money changes hands. If you bought it, it’s because you needed it.

Yet if it’s as simple as that, how can we explain this orgy of debt-fuelled consumption in the last decade or so? Surely these “needs” of ours haven’t increased over time, have they? On the contrary, for a lot of us in the so-called developed world, they’ve diminished quite a bit. A couple of centuries ago, I could have presented a persuasive list of “needs” to anyone who cared to cater to them, from nutrition and personal hygiene to transportation and telecommunication. But now? I don’t know about you, but I’m kind of running out of really pressing problems that could be solved with a trip to the mall. When fortunes can be made by combining tooth-whitening agents with mouthwash, or by devising a way for your car to recognize your mobile phone so that you can have conversations through the stereo, marketers have got to be scraping the bottom of the needs barrel.

To me, this is a paradox. If marketing is about needs, and we need less today than we ever have, why is there more marketing? More perplexing still, why does it seem to be working? Working so well, in fact, that it risks destroying our way of life? Either marketing never was about needs in the first place, or none of us understood what a need really was.

Well, almost none of us. Most people with a passing interest in psychology have at some point run into the work of Abraham Maslow. His Hierarchy of Needs is a staple theory of the science, and it’s been sticky and viral because of its intuitive and simple logic: We humans will focus our attention on meeting needs in a predictable sequence, and that sequence will put matters of survival first and self-actualization last. In other words, nobody is going to give much thought to his personal value system or his inner child if he’s hungry and cold. Conversely, if a person is relatively safe, warm, and well fed, and enjoys the support of a social system, she will have time to spend on the bigger questions of morality and her purpose in the world. These then become her “needs.” This logic presents two interesting implications for what marketing really is: First, it says that our definition of “needs” is fluid and contextual. Second, it says that what motivates the way we meet our needs evolves inevitably from being a matter of survival – I’m hungry – to something more to do with self-expression – This is who I am.

Maslow proposed his hierarchy as a way of explaining individual human behaviour. But can it explain the behaviour of societies, too? Do we collectively move in a way that mirrors our individual behaviours? I think, more often than not, we do. When you look at our collective hierarchy of needs, it would be hard to dispute that, as a group, we’ve worked our way considerably up the ladder over the past century, and that many of us are fortunate enough to have our basic needs consistently met. When an entire community has its basic needs met, it will inevitably tend to turn its attention to values, and to the pursuit of self-esteem, achievement, and enlightenment. Without fear, societies evolve more freely. It’s our collective aspiration. As if to underscore the point, it seems like only yesterday that the United States inaugurated a president whose election campaign made a point of speaking more loudly to our better selves than it did to our fear of real or imagined threats to our survival. Based on the world’s reaction back on that giddy November 4, 2008, election night, humanity seemed ready to ascend, ready to dedicate ourselves to being better rather than just being safe. Collective self-actualization was nigh. We were buying it big time.

Yet a little more than three weeks after that night, on November 29, 2008 – Black Friday, so named because it’s the time of year when American retailers are said to cross the line between losing and making money, and the official start of the holiday shopping season – a temporary worker at the Walmart at Green Acres Mall in Valley Stream, New York, was trampled to death by a mob of shoppers. They had been gathering in front of the store since the previous day, champing at the bit to take advantage of bargains. The local police had deployed crowd control officers as early as 3:30 a.m., and by 5:00 a.m., according to a New York Times reporter, “The crowd of more than 2,000 had become a rabble and could be held back no longer.” A rabble? At Walmart? It was an unusually dramatic expression of the mania of consumerism, with a tragic and thankfully rare result. But its symbolic power is undeniable: Here, on the pivotal day of the year when retailers were finally moving into the black, they seemed to be depending on humanity’s worst urges to do it. The scene, according to an investigating police officer, was “utter chaos,” and the crowd “out of control.” And the lure was not sustenance or shelter or escape from predators, but video games, paper towels, power tools, and fleece wear. We were still buying those, too.

Again, this just doesn’t make sense. Something is broken, here. On the one hand, we have those opportunistic marketers: Believing that their role in the world is to relieve us of our money by meeting our “needs,” they sell us everything as though our lives depended on buying it. Their default tool is urgency. Urgency to whiten and deodorize, to seem more prosperous than our neighbours, to pay less than those same neighbours in the process, to act now before it’s all gone. High-definition televisions are being brought to market as urgently as if they were bags of rice thrown to the starving from the backs of Red Cross trucks. On the other hand, scrambling after them are we, the consumers. Made fools of once too often, egged on by pundits, too vain to acknowledge our own vanity, we behave as if consumption were a competitive sport in which whoever gets the most for the least wins. Which is surely not the path to self actualization, or any other legitimate need for that matter. We and the marketers who sell to us have locked ourselves into a kind of destructive codependency. Is it any wonder we’re all in debt? Is it any wonder that vast economies are erupting in far-flung corners of the planet premised solely on the making of more things for less money? Is it any wonder that the planet is groaning under the strain?

No, it is not. What’s amazing, in fact, is that things aren’t worse than they are.

I don’t think I’m alone in observing this, either. I think people are beginning to feel a sense of culpability. I’ve lived through a few Main Street recessions, but never one that raised the questions that this one has about the morality of consuming: about how much is enough; about the social meaning of material things, or whether the things we buy should have any social meaning at all; about personal accountability. We aren’t necessarily saying so out loud, but we know we had a hand in this.

Still, if history teaches us nothing else, it certainly teaches us that humans won’t bear the weight of repentance for long. We don’t like hair shirts, even if they are on sale. We are built to be hopeful. So, in the next short while, two things will inevitably happen. First, people will look for someone that history can blame for this so they can get on with their lives. And second, people will return to some modified version of their natural state, which, here in the “developed world,” means consuming. What worries me is, we really will blame branded marketing. When the dust has settled and everyone feels we’ve flagellated ourselves enough, we’re going to decide once and for all that corporations and their evil organ grinder’s monkeys, brands, have been the problem.

But before we toss the bathwater of marketing out the window, let’s make sure we see the brand baby for what it is, and for what it could be. So what is it?

Imagine that you have a headache.

Unable to stand it any more, you make for the nearest drug store and face the shelf where they keep the pain relievers. If you are like roughly a third of North Americans, you will reach for Tylenol. Why? Right next to it, there is a generic product that is identical — I mean identical — in its formulation. It contains 325 mg of acetaminophen per tablet, just like regular Tylenol. It is dollars cheaper, pharmacologically the same, and, by statute, therapeutically equivalent. Why on earth are you paying more? Are you a fool?

No, you are not. Whether or not you’re willing to admit it, that extra couple of dollars is buying you two kinds of insurance: One, that you can delegate to Johnson & Johnson the task of solving your headache rather than having to learn the pharmacology of acetaminophen for yourself. And, two, that if something goes wrong, someone will take responsibility.

One day, in 1982, something did go wrong. A murderer tampered with Tylenol on the shelves of a Chicago drug store, and killed seven people. Johnson & Johnson’s response became a case study in public relations. From their unprecedented transparency with the press, to their willingness to destroy millions of dollars’ worth of product as a precaution, to their rapid and brilliant innovation of security features, they did everything right and quickly. Their market share fell to 7 per cent from 37 per cent in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, but it rebounded to 30 per cent within twelve months of the incident. They remain today the most trusted analgesic brand in the market.

When this happened, the corporation that makes Tylenol did more than they had to do. Even allowing for some margin of human decency, there is an important practical reason why Johnson & Johnson took responsibility so completely and so vigorously: their brand. The fame of the Tylenol name made their response to the crisis public. Consumers became a jury, and this was Tylenol’s trial of a lifetime.

That’s why we pay more than we need to for a lot of the products we buy. That’s why brands matter to us, however secretly or unconsciously. Because they make corporations accountable, and in doing that they give us power.

In Consumer Republic, I want to do three things:

First, I want to convince you that you have this power. I’m going to give you a glimpse behind the curtain of marketing and show you the role that we as consumers really play in that process.

Then, I’m going to offer a different, more contemporary, and relevant way to look at the role that brands and consumption play in our lives. I want to convince you that we need to bury the idea of status, right now, and that something much healthier and more interesting is already starting to replace it. In doing this, I hope to convince you that making brands work for us is much more satisfying and productive than pretending they don’t matter.

Finally, I want to get you excited about why this is our moment. We’re warned constantly that we should expect less from the future than we became accustomed to in the past. I think that means we should also expect better, and I think we finally have in our hands the means to say so and the power to back it up. Commerce has come a long way from the time when the only indication of the health of a marketer’s business was whether the merchandise was moving or not. Now, they can see and hear trouble coming before it gets there. Now, as never before, marketers can be influenced to do what we want them to do, as a condition of remaining in business.

Consumer Republic isn’t about guilt and doom. It’s about possibility. This moment in our history, with its crisis and its empowering social and technological changes, has finally given consumers the genuine autonomy we were meant to have all along. This book is about what to do with it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Bruce Philp is a master of his subject, and he offers his readers a thoroughly gratifying peek into the inner world of branding. Consumer Republic bristles with insight and with wit."

—Stephanie Nolan, author of 28

"An utterly foundation-shaking argument that the consumerism responsible for plundering this planet is the only thing that can save it. By changing the way we buy, we can dominate the agenda of every major corporation. Maybe the most astonishing aspect of this idea is that it comes from an adman."

—Terry O'Reilly, author of The Age of Persuasion

"It is refreshing to have someone with Bruce's expertise bring clarity to an often chaotic and confusing area of practice. He not only shows us where we've been, but leads the way to the world of tomorrow."

— Rahaf Harfoush, author of Yes We Did: An Insider's Look at How Social Media Built the Obama Brand

From the Hardcover edition.

—Stephanie Nolan, author of 28

"An utterly foundation-shaking argument that the consumerism responsible for plundering this planet is the only thing that can save it. By changing the way we buy, we can dominate the agenda of every major corporation. Maybe the most astonishing aspect of this idea is that it comes from an adman."

—Terry O'Reilly, author of The Age of Persuasion

"It is refreshing to have someone with Bruce's expertise bring clarity to an often chaotic and confusing area of practice. He not only shows us where we've been, but leads the way to the world of tomorrow."

— Rahaf Harfoush, author of Yes We Did: An Insider's Look at How Social Media Built the Obama Brand

From the Hardcover edition.