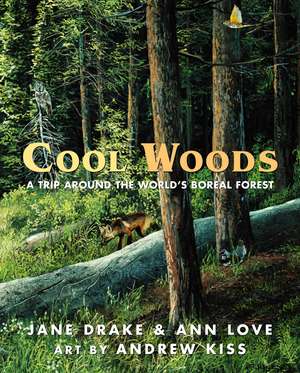

Cool Woods: A Trip Around the World's Boreal Forest

Autor J. Ed. Drake, Jane Drake, Ann Loveen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 aug 2003 – vârsta de la 9 până la 12 ani

The boreal forest is the last great forest wilderness on earth. It drapes across the subarctic right around the world. It pervades our myths and folklore. It provides us with wood and water. It freshens the very air we breathe.

Jane Drake and Ann Love take the reader on an unforgettable journey around the world to view the boreal forest. They show the reader the seasons in the bush, the science and myth of wolves, the life cycle of the woods. From the Siberian Taiga, where tigers and sika deer live, to the Old World forests of Norway, from the Boreal Shield of North America to the birch forest of Northwest Russia, we are introduced to a region of incredible importance. Despite our reliance on it, we have placed the “lungs of the earth” under siege with clear-cutting, acid rain, and even radioactivity.

Cool Woods is not only informative and beautiful, but it is a call to action to anyone who cares about our planet.

Preț: 116.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.34€ • 24.26$ • 18.77£

22.34€ • 24.26$ • 18.77£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780887766084

ISBN-10: 0887766080

Pagini: 80

Dimensiuni: 213 x 257 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

ISBN-10: 0887766080

Pagini: 80

Dimensiuni: 213 x 257 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Tundra Books (NY)

Notă biografică

Jane Drake and Ann Love are sisters and co-authors who have shared a life-long interest in the environment and the wild. Their writing for children has always had a natural history/environmental-action focus. They are interested in making children more observant of the natural world. Together they are the authors of many award- winning books, including their most recent, The Kids Winter Cottage Book. They have been short-listed for numerous awards including the Red Cedar Award, the Norma Fleck Award, the Hackmatack Award, and the Silver Birch Award. Jane Drake is one of the founding members of Pollution Probe. Both Jane and Ann are married with three children each and live in the Toronto area.

Andrew Kiss came to Canada from Hungary in 1957. He grew up on Vancouver Island teaching himself how to paint while working as a topographical draftsman. He paints wildlife, primarily birds, and has spent much of his life traveling the world to see his subjects in their natural habitats. Andrew Kiss’s work has been exhibited across North America and Europe. Cool Woods is his fourth book with Tundra.

Andrew Kiss came to Canada from Hungary in 1957. He grew up on Vancouver Island teaching himself how to paint while working as a topographical draftsman. He paints wildlife, primarily birds, and has spent much of his life traveling the world to see his subjects in their natural habitats. Andrew Kiss’s work has been exhibited across North America and Europe. Cool Woods is his fourth book with Tundra.

Extras

FOREVER GREEN

Step into the woods. The wet ground – springy with moss – soaks your shoe. The soft-green needles of the spruce tree tickle the palm of your hand. Above, a chocolate shadow presses against the trunk. One wink reveals a boreal owl, daydreaming of voles and chickadees. Speckled summer sunlight catches a mound of dog-tongued lichen but misses a nearby wood frog. Shut your eyes and breathe deeply. A wild mix of skunk, damp mushrooms, and fragrant fir tingles your nose. Brush the mosquito from your ear and listen to the woodpecker’s staccato beat.

These are the cool, northern woods that encircle the world. To return the hug, we are learning to care for them, the largest forest left on Earth.

***

WOLF CALL

Around the world, people hear the haunting howls of a wolf pack and think of the wild northern forest. From prehistoric times, wolf lore has crept into people’s imaginations. Some fear wolves; others shoot them. But many understand and admire these intelligent carnivores.

Crying Wolf?

Wolves don’t cry, they howl – to define territory, gather family, and warn intruders.

Thrown to the Wolves?

Wolves are villains in stories. But you’re more likely to be struck by an asteroid than eaten by a wolf. Healthy wolves avoid people.

Wolf Down Food?

Sharp teeth and strong jaws make powerful eating machines. A wolf meal is meat, and lots of it – up to 9 kg (20 pounds), about 80 hamburgers worth, at a time.

***

WINTER IN THE WOODS

A still, bitter cold settles on the forest this January afternoon. The spruce trees stand rigid, resisting the occasional gust of wind. From its snow-covered branch, a red squirrel scolds a pine grosbeak as the bird snaps up the last frozen blueberry on a nearby bush. The temperature is well below zero and falling

In the north woods, temperatures stay below freezing for more than half the year. And the ground is often snow-covered from October until May. With everything frozen for so long, winter is also dry. Yet resident birds and animals survive the meanest of winters, as do the trees that shelter them. Northern trees actually prefer long, dry winters. Coniferous spruce, fir, pine, and larch have adapted to the harsh climate in special ways:

Conical shape: Heavy snow slides off conifers rather than weighing down and breaking branches.

Needles: Trees lose less water through thin, waxy needles than through leaves.

Evergreen: Most conifers don’t waste energy growing needles each year. And by staying dark green year round, the needles absorb some heat from the winter sun.

Shallow roots: The farther north you go, the longer the ground stays frozen in spring. In the farthest north, only the top layer thaws above permanently frozen ground, or permafrost. Northern trees have shallow roots that spread sideways to draw up water as soon as the ground surface melts.

Deciduous Survivors

Northern birch, alder, and young aspen are adapted to survive winter too. Their branches will bend in half before snapping under heavy snow.

***

FIRE! FIRE!

Springtime is fire time. The sun shines more than twelve hours a day. Dried by winter’s wind, pine needles ignite quickly. Fire wipes the woods clean by devouring undergrowth and debris; healthy, sick, and weak trees; wildlife and insects. Native trees can take the heat – they’re adapted to regrow after fire. Intense flames release seeds from hardy pinecones while ash enriches the soil and protects germinating seeds.

As the smoke clears, in move the wood-eating beetles. Beetle-eating woodpeckers quickly follow. Fireweed, berries, and grasses sprout from the ashes, and moose nibble their tender shoots. Aspen and birch send up new saplings from old root systems, and jack pine and spruce quickly reestablish. Ten years later, a diverse woodland community has taken over.

The woods cope with – in fact need – some fire. Small fires caused by lightning strikes are as natural as wind and snow. But human activities such as camping, road building, mining, and logging increase the number of fires. Some of these fires are monsters, roaring through the woods, destroying everything in their path as billions of trees go up in smoke. A warming world alters the forest’s ability to regenerate after a fire, as higher temperatures and less rain hampers growth.

Satellite images lead water-bombers and skilled firefighters to forest-fire hot spots. But allowing small, remote fires to burn out on their own is one key to the future health of the forests.

***

THE GOOD FOREST

The north woods have many names. Some people call them boreal forest after Boreas, Greek god of the north wind. Others call them taiga, a Russian word for marshy woods, although many scientists save the word taiga for the wet, scrubby woods that border the arctic tundra. But to most northerners, the north woods are the bush – beautiful, wild, and full of trees.

From earliest times, people have gone into the bush for resources. They have hunted forest animals, collected firewood, gathered mushrooms and berries, and chosen strong, lean trunks for tent poles. Today, we still cut spruce to frame our homes. We use larch to make telephone poles and railroad ties; jack pine for sturdy posts, pilings, and timber. And fine white spruce gives special resonance to our musical instruments. But most of the northern trees we cut are mashed into pulp for making paper.

We also use the boreal forest by just letting it grow. And the boreal forest uses us. Like all living plants, trees grow by taking carbon dioxide from the air and releasing oxygen. Like all living animals, we do the reverse – our lungs take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide. The boreal forest is the biggest forest left in the world – bigger than the tropical rain forest. So, when you breathe, some of the air you inhale is likely fresh, sweet oxygen from the boreal forest. And some of what you exhale will eventually become part of a living boreal tree. That’s why environmentalists call the boreal forest “the lungs of the Earth.”

***

AROUND THE BOREAL WORLD

If you walked around the world through the boreal forest, you’d find few roads. As you bushwhacked through woods and wetlands, you’d notice many of the plants and animals were the same whether you were in North America, Siberia, or Europe. But you’d also spot important changes in the landscape and the kinds of trees and animals you were seeing. In places, you’d run into logging, mining, industry, and hydroelectric development. You’d also find people living off the land as their ancestors did. You might discover relics from early settlements – maybe even a ghost town. And in each community or homestead you’d meet people who tell their own exciting tales about the woods.

This book divides the forest into six sections or eco-zones – all boreal, but each with a life and story of its own.

Step into the woods. The wet ground – springy with moss – soaks your shoe. The soft-green needles of the spruce tree tickle the palm of your hand. Above, a chocolate shadow presses against the trunk. One wink reveals a boreal owl, daydreaming of voles and chickadees. Speckled summer sunlight catches a mound of dog-tongued lichen but misses a nearby wood frog. Shut your eyes and breathe deeply. A wild mix of skunk, damp mushrooms, and fragrant fir tingles your nose. Brush the mosquito from your ear and listen to the woodpecker’s staccato beat.

These are the cool, northern woods that encircle the world. To return the hug, we are learning to care for them, the largest forest left on Earth.

***

WOLF CALL

Around the world, people hear the haunting howls of a wolf pack and think of the wild northern forest. From prehistoric times, wolf lore has crept into people’s imaginations. Some fear wolves; others shoot them. But many understand and admire these intelligent carnivores.

Crying Wolf?

Wolves don’t cry, they howl – to define territory, gather family, and warn intruders.

Thrown to the Wolves?

Wolves are villains in stories. But you’re more likely to be struck by an asteroid than eaten by a wolf. Healthy wolves avoid people.

Wolf Down Food?

Sharp teeth and strong jaws make powerful eating machines. A wolf meal is meat, and lots of it – up to 9 kg (20 pounds), about 80 hamburgers worth, at a time.

***

WINTER IN THE WOODS

A still, bitter cold settles on the forest this January afternoon. The spruce trees stand rigid, resisting the occasional gust of wind. From its snow-covered branch, a red squirrel scolds a pine grosbeak as the bird snaps up the last frozen blueberry on a nearby bush. The temperature is well below zero and falling

In the north woods, temperatures stay below freezing for more than half the year. And the ground is often snow-covered from October until May. With everything frozen for so long, winter is also dry. Yet resident birds and animals survive the meanest of winters, as do the trees that shelter them. Northern trees actually prefer long, dry winters. Coniferous spruce, fir, pine, and larch have adapted to the harsh climate in special ways:

Conical shape: Heavy snow slides off conifers rather than weighing down and breaking branches.

Needles: Trees lose less water through thin, waxy needles than through leaves.

Evergreen: Most conifers don’t waste energy growing needles each year. And by staying dark green year round, the needles absorb some heat from the winter sun.

Shallow roots: The farther north you go, the longer the ground stays frozen in spring. In the farthest north, only the top layer thaws above permanently frozen ground, or permafrost. Northern trees have shallow roots that spread sideways to draw up water as soon as the ground surface melts.

Deciduous Survivors

Northern birch, alder, and young aspen are adapted to survive winter too. Their branches will bend in half before snapping under heavy snow.

***

FIRE! FIRE!

Springtime is fire time. The sun shines more than twelve hours a day. Dried by winter’s wind, pine needles ignite quickly. Fire wipes the woods clean by devouring undergrowth and debris; healthy, sick, and weak trees; wildlife and insects. Native trees can take the heat – they’re adapted to regrow after fire. Intense flames release seeds from hardy pinecones while ash enriches the soil and protects germinating seeds.

As the smoke clears, in move the wood-eating beetles. Beetle-eating woodpeckers quickly follow. Fireweed, berries, and grasses sprout from the ashes, and moose nibble their tender shoots. Aspen and birch send up new saplings from old root systems, and jack pine and spruce quickly reestablish. Ten years later, a diverse woodland community has taken over.

The woods cope with – in fact need – some fire. Small fires caused by lightning strikes are as natural as wind and snow. But human activities such as camping, road building, mining, and logging increase the number of fires. Some of these fires are monsters, roaring through the woods, destroying everything in their path as billions of trees go up in smoke. A warming world alters the forest’s ability to regenerate after a fire, as higher temperatures and less rain hampers growth.

Satellite images lead water-bombers and skilled firefighters to forest-fire hot spots. But allowing small, remote fires to burn out on their own is one key to the future health of the forests.

***

THE GOOD FOREST

The north woods have many names. Some people call them boreal forest after Boreas, Greek god of the north wind. Others call them taiga, a Russian word for marshy woods, although many scientists save the word taiga for the wet, scrubby woods that border the arctic tundra. But to most northerners, the north woods are the bush – beautiful, wild, and full of trees.

From earliest times, people have gone into the bush for resources. They have hunted forest animals, collected firewood, gathered mushrooms and berries, and chosen strong, lean trunks for tent poles. Today, we still cut spruce to frame our homes. We use larch to make telephone poles and railroad ties; jack pine for sturdy posts, pilings, and timber. And fine white spruce gives special resonance to our musical instruments. But most of the northern trees we cut are mashed into pulp for making paper.

We also use the boreal forest by just letting it grow. And the boreal forest uses us. Like all living plants, trees grow by taking carbon dioxide from the air and releasing oxygen. Like all living animals, we do the reverse – our lungs take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide. The boreal forest is the biggest forest left in the world – bigger than the tropical rain forest. So, when you breathe, some of the air you inhale is likely fresh, sweet oxygen from the boreal forest. And some of what you exhale will eventually become part of a living boreal tree. That’s why environmentalists call the boreal forest “the lungs of the Earth.”

***

AROUND THE BOREAL WORLD

If you walked around the world through the boreal forest, you’d find few roads. As you bushwhacked through woods and wetlands, you’d notice many of the plants and animals were the same whether you were in North America, Siberia, or Europe. But you’d also spot important changes in the landscape and the kinds of trees and animals you were seeing. In places, you’d run into logging, mining, industry, and hydroelectric development. You’d also find people living off the land as their ancestors did. You might discover relics from early settlements – maybe even a ghost town. And in each community or homestead you’d meet people who tell their own exciting tales about the woods.

This book divides the forest into six sections or eco-zones – all boreal, but each with a life and story of its own.

Recenzii

“…totally right on…”

–The Globe and Mail

“The design and engaging writing style make this book fresh and appealing. Highly Recommended.”

–CM Magazine

“…informative and beautiful…. The text conveys a sense of wonder along with its many facts…. [L]ovingly detailed paintings…teem with life…. [T]he authors provide a glossary, an index, and an indispensable map for this intriguing trip, and many young readers will be inspired to find out more.”

–Quill & Quire

–The Globe and Mail

“The design and engaging writing style make this book fresh and appealing. Highly Recommended.”

–CM Magazine

“…informative and beautiful…. The text conveys a sense of wonder along with its many facts…. [L]ovingly detailed paintings…teem with life…. [T]he authors provide a glossary, an index, and an indispensable map for this intriguing trip, and many young readers will be inspired to find out more.”

–Quill & Quire