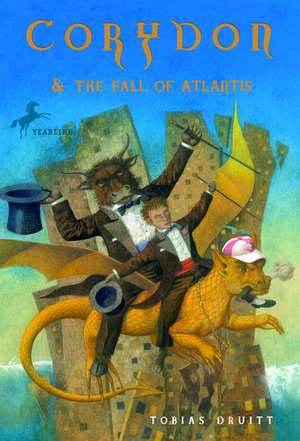

Corydon and the Fall of Atlantis

Autor Tobias Druitten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2034

But Corydon doesn’t feel like a hero—everything seems to be going wrong. His friend the Minotaur is missing, so Corydon and his fellow monsters leave their Island to search for him. Their travels across Poseidon’s treacherous waters involve one narrow escape after another until, at last, they reach the fabled island of Atlantis. And Atlantis is more seductive, monstrous, and volatile that anything they’ve encountered.

Preț: 27.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 42

Preț estimativ în valută:

5.35€ • 5.83$ • 4.51£

5.35€ • 5.83$ • 4.51£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440422174

ISBN-10: 0440422175

Pagini: 272

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: Random House Children's Books

Colecția Yearling

ISBN-10: 0440422175

Pagini: 272

Greutate: 0.11 kg

Editura: Random House Children's Books

Colecția Yearling

Recenzii

“So rich is his take on ingeniously twisted mythology, punctuated by exciting, Odyssey-like encounters (capped, of course, by a truly cataclysmic climax), that readers, particularly fans of Gerald Morris’s Arthurian fantasies, will be riveted from start to finish.” —Kirkus Reviews, Starred

Notă biografică

Tobias Druitt is a pen name for the mother-and-son writing team of Diane Purkiss and Michael Dowling. Purkiss is on the faculty of Oxford University, and Dowling attends the prestigious Dragon School. They live in Oxford, England.

Extras

one

Corydon ran toward the cliff. He could hear the goat’s plaintive bleating. As he ran, he called hastily, “Gorgos! Gorgos, where are you? I need your help and I need it now!”

There was no answer. Corydon was not surprised, but he still felt a chill.

He had reached the edge of the cliff. He lay flat on his stomach and peered over the edge, the blue glitter of the sea below burning his eyes. There, halfway down the cliff, was a narrow ledge, and on it was a goat, lying on her side, bleating faintly. She did not have the energy to rise.

“Eripha,” Corydon crooned, hoping the beast could hear her own name, the tender name he had given her when she was a tiny dancing kid. But she made no response.

“Gorgos!” Corydon shouted once more. Again there was no reply from Medusa’s half-divine son. Furious, Corydon began lowering himself over the edge of the cliff, his feet feeling for footholds. There were small crannies in the straight rock wall, and his eager toes and then fingers found them, though as the cliff crumbled, he had to hurry from one hold to another before they broke to powder in his urgent grasp. His sturdy goat hoof helped him keep his footing.

He had no idea how he would get back up the cliff, but he couldn’t leave Eripha on the ledge; the animal might take fright and slide over.

A handhold gave way, and for one very long moment, Corydon was dangling by one hand from a stiff thyme bush jutting from the cliff edge.

Then, to his relief, his foot felt the dust of the ledge where Eripha waited, her yellow eyes glazed and dull.

He took off his short rope belt and, bending down, tied the animal’s near foreleg to his wrist. She bleated.

Then he sat down and gazed angrily at the sea.

Where was Gorgos? And where had he been when Eripha had stumbled over the edge in the first place? He was supposed to be looking after the goats.

After a few more minutes of fury, Corydon’s thoughts stopped whirling and began to slow.

He had been too angry to think before.

He was thinking now, and it was painful.

Why hadn’t he asked the immortal Gorgons, Sthenno and Euryale, to help him? They often did when sheep were trapped. Why hadn’t he brought some rope? Why had he left his flock with Gorgos in the first place?

Corydon should have known what Gorgos was like. After all, they’d spent six months together. A winter of storytelling and songs by a warm hearth, listening to the riddles of the Sphinx, Euryale’s hunting tales, Sthenno’s excitement over new prophecies. A winter of drying herbs and eating cheese. A winter in which he, Corydon, had turned their own adventure in fighting the seething army of heroes bent on destroying them into a memory, and then into an epic song.

Then with the lengthening days came lambs, lambs, lambs, born into the heavy snow of the mountains. Some of them born in terrible, bitter agony that reminded him of the birth of Gorgoliskos. He could hardly bear to think of that day.

And he had to care for the ewes and the lambs they bore. The weakly little lambs, especially. The mothers sometimes rejected them, and Corydon became their mother, feeding them and sleeping by them to keep their shivering little bodies warm.

Oddly, his favorite ewe had rejected her lamb this year.

It made Corydon wonder about his own mother. And about Gorgos.

Corydon had tried his utmost to teach Gorgos the art of shepherding. But Gorgos never seemed to understand.

When Corydon told him that it was important for pregnant ewes to get special grass, hand-pulled from the lush slopes lower down on the mountains, Gorgos laughed and said it was too much work. Corydon had found Gorgos keeping one great-bellied ewe on a snowy mountaintop with no green food for miles. She was gaunt and wild-eyed, and Corydon had nursed her by hand for two weeks to bring her back up to strength.

Gorgos couldn’t sit and watch sheep or goats and do a little piping. He was only happy when running feverishly on the hillside, playing wild games that only he seemed to understand, acting out strange, half-remembered hero tales of the deaths of kings and the burning of cities. The only animal Corydon had ever seen him care for, or even watch, was a wolf that had once ventured among the sheep in winter. Gorgos had stalked the wolf, imitating its movements, and then stared at it, like a wolf himself. To Corydon’s surprise, the wolf had retreated before the snarling boy, bowing his head in submission. Gorgos had one deep scratch from this encounter but had hardly noticed it. He never noticed bruises or wounds that would have made other boys limp or cry.

The only other creature Gorgos found interesting was the nightingale that sang every night in the hazel tree. As she tuned up for spring, daily improving her song, Gorgos would stop running around the mountainside to listen, in a stillness so complete that it reminded Corydon of the way a wild animal sits looking at the moon. Corydon liked her song, too, but Gorgos seemed to hear in it something that no one else could detect.

As he sat on the ledge, thinking slowly of these things in the careful shepherd’s way, Corydon couldn’t help feeling angry all over again. Where was Gorgos?

His rage made him feel lonely. He had hoped that Gorgos would be his friend, as Gorgos’s mother, Medusa, had been. He had begun to see that Gorgos was not the same as his mother but entirely different. It was like losing her a second time.

It hurt because it meant he was alone.

Well, not really alone, he told himself quickly. There were the other monsters, after all, and they were his friends. It was too long since he had seen the Minotaur or the Snake-Girl, though. After the Battle of Smoke and Flame, after the heroes had departed, the monsters had gone their separate ways, each drifting back to his or her own solitary life. They had met only twice in the last, long, working year: once at grape-harvest time and once in the first bright days of spring, when the hills were mantled with flowers. Corydon loved those festival days. Even the villagers were less wary of him now, not eager to have him among them still, but willing to buy his cheeses.

From the Hardcover edition.

Corydon ran toward the cliff. He could hear the goat’s plaintive bleating. As he ran, he called hastily, “Gorgos! Gorgos, where are you? I need your help and I need it now!”

There was no answer. Corydon was not surprised, but he still felt a chill.

He had reached the edge of the cliff. He lay flat on his stomach and peered over the edge, the blue glitter of the sea below burning his eyes. There, halfway down the cliff, was a narrow ledge, and on it was a goat, lying on her side, bleating faintly. She did not have the energy to rise.

“Eripha,” Corydon crooned, hoping the beast could hear her own name, the tender name he had given her when she was a tiny dancing kid. But she made no response.

“Gorgos!” Corydon shouted once more. Again there was no reply from Medusa’s half-divine son. Furious, Corydon began lowering himself over the edge of the cliff, his feet feeling for footholds. There were small crannies in the straight rock wall, and his eager toes and then fingers found them, though as the cliff crumbled, he had to hurry from one hold to another before they broke to powder in his urgent grasp. His sturdy goat hoof helped him keep his footing.

He had no idea how he would get back up the cliff, but he couldn’t leave Eripha on the ledge; the animal might take fright and slide over.

A handhold gave way, and for one very long moment, Corydon was dangling by one hand from a stiff thyme bush jutting from the cliff edge.

Then, to his relief, his foot felt the dust of the ledge where Eripha waited, her yellow eyes glazed and dull.

He took off his short rope belt and, bending down, tied the animal’s near foreleg to his wrist. She bleated.

Then he sat down and gazed angrily at the sea.

Where was Gorgos? And where had he been when Eripha had stumbled over the edge in the first place? He was supposed to be looking after the goats.

After a few more minutes of fury, Corydon’s thoughts stopped whirling and began to slow.

He had been too angry to think before.

He was thinking now, and it was painful.

Why hadn’t he asked the immortal Gorgons, Sthenno and Euryale, to help him? They often did when sheep were trapped. Why hadn’t he brought some rope? Why had he left his flock with Gorgos in the first place?

Corydon should have known what Gorgos was like. After all, they’d spent six months together. A winter of storytelling and songs by a warm hearth, listening to the riddles of the Sphinx, Euryale’s hunting tales, Sthenno’s excitement over new prophecies. A winter of drying herbs and eating cheese. A winter in which he, Corydon, had turned their own adventure in fighting the seething army of heroes bent on destroying them into a memory, and then into an epic song.

Then with the lengthening days came lambs, lambs, lambs, born into the heavy snow of the mountains. Some of them born in terrible, bitter agony that reminded him of the birth of Gorgoliskos. He could hardly bear to think of that day.

And he had to care for the ewes and the lambs they bore. The weakly little lambs, especially. The mothers sometimes rejected them, and Corydon became their mother, feeding them and sleeping by them to keep their shivering little bodies warm.

Oddly, his favorite ewe had rejected her lamb this year.

It made Corydon wonder about his own mother. And about Gorgos.

Corydon had tried his utmost to teach Gorgos the art of shepherding. But Gorgos never seemed to understand.

When Corydon told him that it was important for pregnant ewes to get special grass, hand-pulled from the lush slopes lower down on the mountains, Gorgos laughed and said it was too much work. Corydon had found Gorgos keeping one great-bellied ewe on a snowy mountaintop with no green food for miles. She was gaunt and wild-eyed, and Corydon had nursed her by hand for two weeks to bring her back up to strength.

Gorgos couldn’t sit and watch sheep or goats and do a little piping. He was only happy when running feverishly on the hillside, playing wild games that only he seemed to understand, acting out strange, half-remembered hero tales of the deaths of kings and the burning of cities. The only animal Corydon had ever seen him care for, or even watch, was a wolf that had once ventured among the sheep in winter. Gorgos had stalked the wolf, imitating its movements, and then stared at it, like a wolf himself. To Corydon’s surprise, the wolf had retreated before the snarling boy, bowing his head in submission. Gorgos had one deep scratch from this encounter but had hardly noticed it. He never noticed bruises or wounds that would have made other boys limp or cry.

The only other creature Gorgos found interesting was the nightingale that sang every night in the hazel tree. As she tuned up for spring, daily improving her song, Gorgos would stop running around the mountainside to listen, in a stillness so complete that it reminded Corydon of the way a wild animal sits looking at the moon. Corydon liked her song, too, but Gorgos seemed to hear in it something that no one else could detect.

As he sat on the ledge, thinking slowly of these things in the careful shepherd’s way, Corydon couldn’t help feeling angry all over again. Where was Gorgos?

His rage made him feel lonely. He had hoped that Gorgos would be his friend, as Gorgos’s mother, Medusa, had been. He had begun to see that Gorgos was not the same as his mother but entirely different. It was like losing her a second time.

It hurt because it meant he was alone.

Well, not really alone, he told himself quickly. There were the other monsters, after all, and they were his friends. It was too long since he had seen the Minotaur or the Snake-Girl, though. After the Battle of Smoke and Flame, after the heroes had departed, the monsters had gone their separate ways, each drifting back to his or her own solitary life. They had met only twice in the last, long, working year: once at grape-harvest time and once in the first bright days of spring, when the hills were mantled with flowers. Corydon loved those festival days. Even the villagers were less wary of him now, not eager to have him among them still, but willing to buy his cheeses.

From the Hardcover edition.