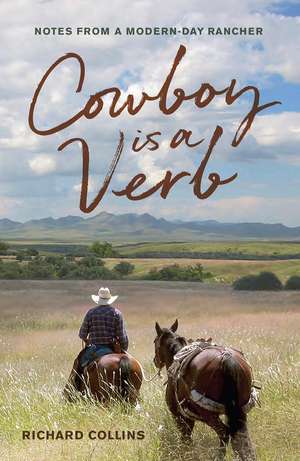

Cowboy is a Verb: Notes from a Modern-day Rancher

Autor Richard Collinsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 noi 2019 – vârsta ani

From the big picture to the smallest detail, Richard Collins fashions a rousing memoir about the modern-day lives of cowboys and ranchers. However, Cowboy is a Verb is much more than wild horse rides and cattle chases. While Collins recounts stories of quirky ranch horses, cranky cow critters, cow dogs, and the people who use and care for them, he also paints a rural West struggling to survive the onslaught of relentless suburbanization.

A born storyteller with a flair for words, Collins breathes life into the geology, history, and interdependency of land, water, and native and introduced plants and animals. He conjures indelible portraits of the hardworking, dedicated people he comes to know. With both humor and humility, he recounts the day-to-day challenges of ranch life such as how to build a productive herd, distribute your cattle evenly across a rough and rocky landscape, and establish a grazing system that allows pastures enough time to recover. He also intimately recounts a battle over the endangered Gila topminnow and how he and his neighbors worked with university range scientists, forest service conservationists, and funding agencies to improve their ranches as well as the ecological health of the Redrock Canyon watershed.

Ranchers who want to stay in the game don’t dominate the landscape; instead, they have to continually study the land and the animals it supports. Collins is a keen observer of both. He demonstrates that patience, resilience, and a common-sense approach to conservation and range management are what counts, combined with an enduring affection for nature, its animals, and the land. Cowboy is a Verb is not a romanticized story of cowboy life on the range, rather it is a complex story of the complicated work involved with being a rancher in the twenty-first-century West.

A born storyteller with a flair for words, Collins breathes life into the geology, history, and interdependency of land, water, and native and introduced plants and animals. He conjures indelible portraits of the hardworking, dedicated people he comes to know. With both humor and humility, he recounts the day-to-day challenges of ranch life such as how to build a productive herd, distribute your cattle evenly across a rough and rocky landscape, and establish a grazing system that allows pastures enough time to recover. He also intimately recounts a battle over the endangered Gila topminnow and how he and his neighbors worked with university range scientists, forest service conservationists, and funding agencies to improve their ranches as well as the ecological health of the Redrock Canyon watershed.

Ranchers who want to stay in the game don’t dominate the landscape; instead, they have to continually study the land and the animals it supports. Collins is a keen observer of both. He demonstrates that patience, resilience, and a common-sense approach to conservation and range management are what counts, combined with an enduring affection for nature, its animals, and the land. Cowboy is a Verb is not a romanticized story of cowboy life on the range, rather it is a complex story of the complicated work involved with being a rancher in the twenty-first-century West.

Preț: 209.13 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 314

Preț estimativ în valută:

40.02€ • 43.46$ • 33.62£

40.02€ • 43.46$ • 33.62£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781948908238

ISBN-10: 1948908239

Pagini: 312

Ilustrații: 23 b-w photos, 3 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

ISBN-10: 1948908239

Pagini: 312

Ilustrații: 23 b-w photos, 3 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Notă biografică

Richard Collins is an award-winning author, rancher, horseman, conservationist, and scholar who has owned and operated farms and ranches on the borderlands of Southern Arizona since 1983.

Extras

Chapter 1. Alamo Spring

In 1990 after much searching, I found a long wedge of magnificent land located in the southern Arizona borderlands, thirty miles north of the Mexican border and fifty-five miles southeast of Tucson, Arizona. Sonoita, the closest town, lay three miles to the north. North to south, the property ran for three-quarters of a mile alongside a back country lane that meandered southward into the mile-high, oak-juniper woodland of the Canelo Hills. The west side bordered the Coronado National Forest and overlooked Alamo Canyon, a deep arroyo that sliced through the rhyolite and limestone hills.

Near the southwestern edge of the property, the canyon surged over a granite uplift and dropped ten feet into a pocket between a jumble of boulders. During the monsoon, the pocket was deep enough to swim. Even during the dry season, it still contained enough water for wildlife. The first time Diane and I rode the canyon, a troop of coati mundi scampered up the yellow lichen-covered boulders, their long tails upright and curved at the tips. As they vanished into the oak brush one turned and stared at me with its quizzical black eyes, raccoon face, and long, upturned snout.

A few yards below the pocket, a smaller tributary joined the main canyon. Together, the two streams sustained a trickle of water between low banks of rocky soil and deer grass. Deer bones scattered in the brush marked the watering hole as an ambush site for mountain lions. Cottonwoods shaded the stream, giving the canyon its Spanish name, Alamo. On that breezy morning, their shimmering leaves sounded like people whispering without words.

The most promising building site on the property nestled in a thicket of oaks and sloped gently in the direction of Mount Wrightson thirty miles to the west across the Sonoita Creek valley. To be sure that it was the right place, Diane and I camped out under the trees for a couple of days before we put our money down. At daybreak, a thin reef of clouds parted on a full moon that loomed over the massive peak just as the sun broke over the eastern horizon behind us. The dawn glow of Mount Wrightson clenched in a haphazard collage of cliffs and trees sealed the deal. Over that entire expanse, nothing man-made interrupted the natural contours. Living in Tucson’s clutter and crowds the year before had shrunk my outlook on life to that of a midge. Here on the high desert grasslands, life would not be so cramped and miserly.

Diane was not so certain. She loved her house in the suburbs, her close friends, the convenient shopping, and her work on School Board where Rich went to high school. But she also loved her horses. We had built up a fine band of broodmares and she managed their careers on the race tracks. An outgoing, energetic person, Diane charmed the best efforts out of the horse trainers and jockeys with her sunny disposition. And the ranch would be a better place to raise horses than in Tucson. When Rich graduated and loped off to college, we made the jump to Sonoita. Right away, Diane joined the Sonoita Cowbelles and also volunteered to help at the Elgin school. With her sparkling personality, she had a natural ability to produce some pleasantry and then light up the room with a sun-dial smile that made the remark mean a whole lot more than it would have if someone else had said it.

Behind the house site one hundred feet south was a rounded knob, flat on top, and perfectly situated for the horse barn with the breezeway facing east to the rising sun over the Mustang Mountains and west overlooking sunsets behind Mount Wrightson. Horses feel more secure when they are able to see long distances and the stunning panorama sure made it easy for me to ride out at dawn and eager to get home and watch the sunset from our back porch.

The backcountry lane ran due north and south, while Alamo Canyon veered northwest from the waterfall toward the main stem of Sonoita Creek. Between the canyon and the lane, the topography was level and had good soil structure for the rooting of oak and juniper, bear grass and cliff rose, as well as a cozy house site for our ranch headquarters. On the downside, a porous limestone formed the geological underpinning of the land that sequestered its water in deep, isolated pockets. We had few neighbors because domestic wells in the area were few and the Coronado National Forest surrounded us on two sides.

As a condition of my purchase, the seller had to drill a well that pumped at least ten gallons a minute. That task fell to Tom Hunt, a veteran cattleman who worked for the seller. Tom was into his sixties when I first met him, but he still stood tall and lanky with a straw hat shading lamb blue eyes and a face creased by a mischievous grin as if he had just heard a good joke and wanted to pass it on. He was also locally renowned as Santa Cruz County’s best water witch.

Tom was also part owner with the seller, an Austrian banker of some nobility who at the time lived in Europe, and both were keen to consummate our deal. Tom’s technique for dowsing a promising well site involved walking over the land with a bent coat hanger held waist high with the hook pointed straight out, level to the ground. The coat hanger (or Tom’s hands) allegedly had an affinity for deep water, in addition to a mind of its own. Where the hook jumped down from Tom’s gnarly fists, he tied a strip of white cloth to a nearby bush. After three weeks of triangulating back and forth to locate the strongest signals more precisely, our potential new property looked like a tattered quilt.

“I’m drilling here,” Tom finally decided. He took a two-by-four stake and hammered it in the ground with a sledge. “We’ll hit water below 250 feet, and pump at least twenty gallons a minute,” he stated confidently.

“Let me try,” I said, taking the coat hanger. I walked back and forth across the drill site with the wire in hand.

"I don’t feel a damn thing, Tom,” I said. “This looks like a lot of hooey to me.” Tom’s grin collapsed into a pained expression like I had just insulted his best bull. “It don’t work for a skeptic,” he said crossly. “You got to believe.” A few days later, the driller hit a strong vein of water at two hundred and fifty-seven feet. When Bailey Foster, the local well man, installed the test pump, the well yielded a steady sixty-five gallons a minute. And this in an area where dry holes nine hundred feet deep were not uncommon, and five gallons a minute was considered a blessing. Tom’s water witching seemed more like a lucky draw to an inside four card straight. Even so, I’ve drilled several other wells since that first one and Tom Hunt witched them all just for insurance.

In 1990 after much searching, I found a long wedge of magnificent land located in the southern Arizona borderlands, thirty miles north of the Mexican border and fifty-five miles southeast of Tucson, Arizona. Sonoita, the closest town, lay three miles to the north. North to south, the property ran for three-quarters of a mile alongside a back country lane that meandered southward into the mile-high, oak-juniper woodland of the Canelo Hills. The west side bordered the Coronado National Forest and overlooked Alamo Canyon, a deep arroyo that sliced through the rhyolite and limestone hills.

Near the southwestern edge of the property, the canyon surged over a granite uplift and dropped ten feet into a pocket between a jumble of boulders. During the monsoon, the pocket was deep enough to swim. Even during the dry season, it still contained enough water for wildlife. The first time Diane and I rode the canyon, a troop of coati mundi scampered up the yellow lichen-covered boulders, their long tails upright and curved at the tips. As they vanished into the oak brush one turned and stared at me with its quizzical black eyes, raccoon face, and long, upturned snout.

A few yards below the pocket, a smaller tributary joined the main canyon. Together, the two streams sustained a trickle of water between low banks of rocky soil and deer grass. Deer bones scattered in the brush marked the watering hole as an ambush site for mountain lions. Cottonwoods shaded the stream, giving the canyon its Spanish name, Alamo. On that breezy morning, their shimmering leaves sounded like people whispering without words.

The most promising building site on the property nestled in a thicket of oaks and sloped gently in the direction of Mount Wrightson thirty miles to the west across the Sonoita Creek valley. To be sure that it was the right place, Diane and I camped out under the trees for a couple of days before we put our money down. At daybreak, a thin reef of clouds parted on a full moon that loomed over the massive peak just as the sun broke over the eastern horizon behind us. The dawn glow of Mount Wrightson clenched in a haphazard collage of cliffs and trees sealed the deal. Over that entire expanse, nothing man-made interrupted the natural contours. Living in Tucson’s clutter and crowds the year before had shrunk my outlook on life to that of a midge. Here on the high desert grasslands, life would not be so cramped and miserly.

Diane was not so certain. She loved her house in the suburbs, her close friends, the convenient shopping, and her work on School Board where Rich went to high school. But she also loved her horses. We had built up a fine band of broodmares and she managed their careers on the race tracks. An outgoing, energetic person, Diane charmed the best efforts out of the horse trainers and jockeys with her sunny disposition. And the ranch would be a better place to raise horses than in Tucson. When Rich graduated and loped off to college, we made the jump to Sonoita. Right away, Diane joined the Sonoita Cowbelles and also volunteered to help at the Elgin school. With her sparkling personality, she had a natural ability to produce some pleasantry and then light up the room with a sun-dial smile that made the remark mean a whole lot more than it would have if someone else had said it.

Behind the house site one hundred feet south was a rounded knob, flat on top, and perfectly situated for the horse barn with the breezeway facing east to the rising sun over the Mustang Mountains and west overlooking sunsets behind Mount Wrightson. Horses feel more secure when they are able to see long distances and the stunning panorama sure made it easy for me to ride out at dawn and eager to get home and watch the sunset from our back porch.

The backcountry lane ran due north and south, while Alamo Canyon veered northwest from the waterfall toward the main stem of Sonoita Creek. Between the canyon and the lane, the topography was level and had good soil structure for the rooting of oak and juniper, bear grass and cliff rose, as well as a cozy house site for our ranch headquarters. On the downside, a porous limestone formed the geological underpinning of the land that sequestered its water in deep, isolated pockets. We had few neighbors because domestic wells in the area were few and the Coronado National Forest surrounded us on two sides.

As a condition of my purchase, the seller had to drill a well that pumped at least ten gallons a minute. That task fell to Tom Hunt, a veteran cattleman who worked for the seller. Tom was into his sixties when I first met him, but he still stood tall and lanky with a straw hat shading lamb blue eyes and a face creased by a mischievous grin as if he had just heard a good joke and wanted to pass it on. He was also locally renowned as Santa Cruz County’s best water witch.

Tom was also part owner with the seller, an Austrian banker of some nobility who at the time lived in Europe, and both were keen to consummate our deal. Tom’s technique for dowsing a promising well site involved walking over the land with a bent coat hanger held waist high with the hook pointed straight out, level to the ground. The coat hanger (or Tom’s hands) allegedly had an affinity for deep water, in addition to a mind of its own. Where the hook jumped down from Tom’s gnarly fists, he tied a strip of white cloth to a nearby bush. After three weeks of triangulating back and forth to locate the strongest signals more precisely, our potential new property looked like a tattered quilt.

“I’m drilling here,” Tom finally decided. He took a two-by-four stake and hammered it in the ground with a sledge. “We’ll hit water below 250 feet, and pump at least twenty gallons a minute,” he stated confidently.

“Let me try,” I said, taking the coat hanger. I walked back and forth across the drill site with the wire in hand.

"I don’t feel a damn thing, Tom,” I said. “This looks like a lot of hooey to me.” Tom’s grin collapsed into a pained expression like I had just insulted his best bull. “It don’t work for a skeptic,” he said crossly. “You got to believe.” A few days later, the driller hit a strong vein of water at two hundred and fifty-seven feet. When Bailey Foster, the local well man, installed the test pump, the well yielded a steady sixty-five gallons a minute. And this in an area where dry holes nine hundred feet deep were not uncommon, and five gallons a minute was considered a blessing. Tom’s water witching seemed more like a lucky draw to an inside four card straight. Even so, I’ve drilled several other wells since that first one and Tom Hunt witched them all just for insurance.

Cuprins

Foreword by George B. Buyle, PhD

Introduction

Chapter 1. Alamo Spring

Chapter 2. Fine Feathers

Chapter 3. Tar Paper and Tin Shacks

Chapter 4. What Goes Around

Chapter 5. Living Close to Predicament

Chapter 6. Rainfall, Cow Counts, and Climate Change

Chapter 7. The Seibold Ranch

Chapter 8. Fences, Fires, and Drug Mules

Chapter 9. More Horses and a Dog

Chapter 10. Canelo Hills Coalition

Chapter 11. Toward a Practice of Limits

Chapter 12. Taking Good Care

Chapter 13. Habitat or Species

Chapter 14. Why in Hell?

Chapter 15. Cowboy is a Verb

Acknowledgments

Selected Sources

About the Author

Introduction

Chapter 1. Alamo Spring

Chapter 2. Fine Feathers

Chapter 3. Tar Paper and Tin Shacks

Chapter 4. What Goes Around

Chapter 5. Living Close to Predicament

Chapter 6. Rainfall, Cow Counts, and Climate Change

Chapter 7. The Seibold Ranch

Chapter 8. Fences, Fires, and Drug Mules

Chapter 9. More Horses and a Dog

Chapter 10. Canelo Hills Coalition

Chapter 11. Toward a Practice of Limits

Chapter 12. Taking Good Care

Chapter 13. Habitat or Species

Chapter 14. Why in Hell?

Chapter 15. Cowboy is a Verb

Acknowledgments

Selected Sources

About the Author

Descriere

Richard Collins seamlessly weaves a memoir about how he learned to ranch in southwestern Arizona with astute commentaries about the challenges of doing so in a land where most of his neighbors were exurbanites and a small endangered minnow caused more problems than the drug runners trekking through his mountain pastures. Along the way, Collins paints a portrait of rural West struggling to survive the onslaught of relentless urbanization, suburbanization, and exurbanization. He poses one of the most consequential questions facing environmentalists today: Do we attempt to preserve every vanishing species regardless of habitat constraints, or should we manage the land for overall ecological health?