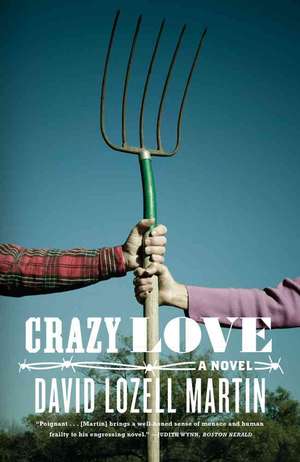

Crazy Love: A Novel

Autor David Lozell Martinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 dec 2008

Joseph Long, known locally as Bear, is a farmer ridiculed by neighbors for his strangeness. Lonely nearly to the point of madness and so desperate for human touch, he leans against the hands of the barber giving him a haircut.

Katherine Renault is a successful career woman, wondering why, if she has the perfect job and the perfect fiancé, does she feel so hollow inside -- even before the illness, the disfiguring surgery.

They should have nothing in common -- though he has a magical touch with animals, he considers them property, while she can't tolerate their mistreatment. She's a sophisticated city dweller who can't abide violence, and he's never traveled beyond the local town and has blood on his hands. But love is crazy, and soon they are rescuing the injured of the world just as they rescue each other. Enduring violence and loss, they live in a domestic bliss wide and deep enough to dilute most of life's dramas, until fate tests them again.

Funny, erotic, emotionally powerful, yet surprisingly unsentimental about our relationships with each other and with animals in our care, Crazy Love will heal broken hearts.

Preț: 107.40 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.55€ • 21.50$ • 17.07£

20.55€ • 21.50$ • 17.07£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781416566632

ISBN-10: 1416566635

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1416566635

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Extras

Chapter 1

Watch time. At 8:30 A.M. on April 19, a farmer named Joseph David Long, known locally as Bear, was on his way into town when he saw two men standing over a cow. Bear stopped his truck to the side of the county road and looked out across the pasture -- a fringe of grassland, a background of forest. Both men laughed. They were far enough away for him to see their heads go back before he heard their laughter, which came a disconnected moment later, as in a poorly dubbed movie. Bear knew that one of the men must be Phil Scrudde because Scrudde's big blue Cadillac was parked right out there in the pasture, next to the cow, which was lying down. Scrudde was famous for driving his Cadillac into pastures and fields, like maybe he thought he was Hud. From this distance, Bear couldn't recognize the other man, taller and thinner.

Quickly now, Scrudde, the shorter fatter man, grabbed up a pitchfork and stuck the cow's flank. Bear's mouth dropped at the sudden cruelty of it and he once again saw movement -- the cow stretching its neck and raising its muzzle at being impaled -- before hearing the cow's sound, a sad trumpet on this empty-stage, frost-chilled April morning. Bear exited his truck and crossed the fence.

More than a fence was crossed of course. To enter that pasture was one of those decisions fat with fate, leading to mayhem. But even if he'd known it at the time, Bear still would've crossed that fence: he was a dangerously uncomplicated man; on occasion he was inevitable.

When they saw him coming, Bear counting steps, Scrudde handed the pitchfork to the taller man, who turned out to be Carl Coote, twenty-five years old and considered handsome by the women. Carl preferred you hold the final e silent when pronouncing his last name, but it was a campaign he had waged without success from first grade on. Carl was called Cootie. He worked for Scrudde because no one else would have him, Carl known as a thief and fistfighter. Word was he wanted to be a rock star, though how he hoped to accomplish this, here in Appalachia, was anyone's guess.

"Hello there, Bear," Scrudde said with a smile like false dawn. "You're just the man we need." Scrudde had a problem with the pronunciation of his last name, too. He wanted you to call him "Scrud," rhymes with Hud and sounds tough, but people who did business with him pronounced it "Screwed," as in I have been...He was a sneaky little man, age fifty-six, who had acquired a fortune through deceit -- cheating widows, for example. He seldom attacked directly but was relentless on the back end of a deal, stabbing you with a lawyer if it came to that. In his younger days he'd been notorious as a dog-poisoner.

"Unless we get this cow to stand," Scrudde continued in that falsely jaunty voice, "she'll die for sure. Now, everybody knows Bear has a way with animals. You get her on her feet for us, what do you say?"

Bear looked down at the cow's rump and counted a dozen puncture wounds oozing thick dark blood. Bear counted things; he was also a name-giver.

"I'll get her up," Coote announced. He wore black jeans and a black cowboy shirt and an open letter-jacket from high school. At his skinny neck you could see the tops of chest tattoos. Coote stuck the cow with two short jabs of the pitchfork, adding six additional puncture wounds and eliciting from the creature another pained bellow.

Bear reached over and took the pitchfork from Coote, who started to protest but was interrupted by Scrudde telling Bear this was all the cow's fault. "No use trying to doctor 'em, Bear, unless you get 'em to stand first, you know that. This one's being contrary." Scrudde wore lizard cowboy boots, wool pants so thick they looked inflated, a denim jacket, and a white cowboy hat. All the other farmers around here called themselves farmers but Scrudde said he was a rancher.

"Gimme that fork back," Coote demanded.

Bear didn't.

As Coote weighed the issue, his tongue squeezed together until it was real fat and then the tip came out between his lips -- a lifelong tic. He was thin but ropy strong, long redneck hair greasy over the shirt collar, his face cut on angles and planes that caught light and cast shadows. Sometimes he played electric guitar with a garage band, more loud than good. Coote practiced sticking out his tongue onstage. He had eyes sleepy with luxury lashes and the lids halfway down, what the women called bedroom eyes, but many men took as insolence. In fact, those eyes and what he did with his tongue made some men want to slap his face on principle, which is what had turned the boy into a fistfighter.

Scrudde, seeing the two men weren't going to engage, at least not just yet, mocked the peacemaker by saying what's important here is not our petty differences, what's important here is saving this poor cow, God's creature. "Bear, can't you get her to stand? That'll save her life, you know it will, give me your opinion."

There was truth to it, a sick cow that's down and won't get up will surrender on the whole idea of living and before you can do any good with food or water or medication, first you got to get that cow on her feet.

Bear, still holding the pitchfork out of Coote's reach, bent to this particular cow, black with a white face, a cross between an Angus bull and a Hereford cow. She was old and had suffered a winter of low-quality hay and no supplemental grain, Scrudde squeezing a few cents more out of each pound of his cattle's flesh. This one was also in severe dehydration owing to the lateness of spring rains. With only a few pools of mud-fouled water in the creeks, cows didn't drink as much as they should. Bear knew that if you cut open this cow right now you'd find bushel baskets of crumbly dry feces blocking her bowels. New green grass could save her, could liquefy and clean her bowels, but it was April and the spring grass hadn't come in earnest yet.

"What'da you say, Bear?" Scrudde urged.

"Shoot her," was what Bear finally said...which surprised the other two because Bear seldom spoke. If you knew this, then pressing him to speak, as Scrudde had been doing, became a form of ridicule.

"Shoot her?" Scrudde took off his cowboy hat, used the inside of his forearm to wipe at his high white forehead, then replaced the hat. "That's fine advice coming from a animal-lover like you." This was not meant as a compliment. "Get her on her feet, she'll be fine."

Bear shook his head because sometimes a failure to stand is not a matter of lethargy or contrariness, sometimes the cow is all but dead but simply won't die, which was the case with this one.

"You wanna buy her?" Scrudde asked. "Everything I own is for sale at the right price, so if you want to buy this cow and save her your own way, let's dicker."

"Shoot her," Bear repeated. Shoot this cow and put her out of misery's reach. Bear had a revolver in his truck, Scrudde undoubtedly had one in that Cadillac there. Just shoot her.

"Company," Coote said.

Bear and Scrudde looked toward the road where another vehicle, an old green Chevy Nova, was parked facing Bear's truck. A woman had crossed the same fence as Bear and was heading toward the three men at a measured pace, almost as if she, like Bear, counted her steps.

*

At eight-thirty that morning, precisely the time Bear first stopped his truck to see what the men were doing with the cow, Katherine Renault had been awakened by a phone call.

"Hi, hope I didn't wake you."

"Who is this?"

"Don't you know? It's Barbara."

Barbara? Katherine had been living in this small town for five months and still wasn't accustomed to the reality that everyone knew her, the expectation that she should know everyone. Who was Barbara? Must be one of the women from the library.

"I did wake you, didn't I?"

Katherine looked at the bedside clock and lied, saying she'd been awake for hours. "What's up?"

Barbara drove a school bus and this morning had seen something nasty, two men sticking a cow with a pitchfork. She told Katherine where, exactly, on the bus route this had happened and said she hoped Katherine would go out there and make the men stop, it was a terrible thing to see.

"How can I make them stop?" Katherine asked, sitting up, wide awake now.

"At the library you were talking about rescuing animals."

"I meant strays, abandoned animals."

"Well that cow needs rescuing more than any stray, those men sticking it with a pitchfork."

Katherine asked why the men would be doing something like that.

Barbara said she didn't know and suggested Katherine go there and find out.

"Can you come with me?"

The woman said no, sorry, she was due back home to make breakfast for her husband. "This is more up your alley," she said. "You know, one of them rescue missions you were talking about."

Katherine started to explain again that she didn't mean rescuing animals from their owners, she meant rescuing strays and putting them up for adoption, but Barbara was already saying good-bye, hope you're able to do some good and save that cow, gotta go, I did my duty by telling you.

It was last year at Thanksgiving that Katherine Renault came here, moved into a little furnished cottage owned by her fiancé. He was always apologizing for owning property in the heart of Appalachia, explaining that he had inherited it from an uncle and decided to keep it as a vacation place, fix it up, diversifying his property portfolio. After Katherine's illness, after the operation, after she got out of the hospital, when she started going crazy because all her friends were so constantly there, doing what friends are supposed to do, offering advice and comfort and company, what Katherine most wanted in the world was some time alone. So her fiancé offered his little hillbilly cottage, as he called it, and Katherine came here intending to stay a few weeks. It had been five months.

Here, people left her alone. Katherine was the one who finally made contact after going stir-crazy, too much TV. She started taking walks around town, seeing notices about meetings at the library: book groups, civic improvement, self-esteem, weight loss. It was at one of the library meetings, attended by women and a few old men, that Katherine mentioned rescuing stray animals. For the last eight years she'd worked as a lobbyist in Washington, D.C., representing nonprofit fund-raising organizations, but before that, back when she got out of college, Katherine had volunteered with groups like Greenpeace and PETA -- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. A person would have to be careful about mentioning animal rights here, Katherine thought -- here in Appalachian farm country where animals are considered personal property, where violence is commonplace and farmers go armed in their fields. Katherine was interested in finding homes for strays, nothing more than that; she was here only temporarily, would be going back to D.C. soon and getting married.

She got out of bed, washed, dressed, and wondered how to approach men who were torturing a cow, what to say to them. Back in D.C., in Katherine's circles, a woman could say something wiseass or provocative to a man, he'd laugh and think the woman was great fun. But not here. Katherine had seen how men here reacted when a woman was smart-alecky, acted flippant or defiant; men would get their backs up and give the woman a bad look under bristly eyes that warned her, you'd better watch your mouth.

Katherine didn't want any part of that throwback behavior. She was here to recover, recuperate, then go home.

Heating water for tea, Katherine watched the two parrots she was caring for as they sidestepped back and forth the lengths of their perches. Outside in the fenced yard, eight dogs were awakening, stretching, walking the perimeter. All these animals had come to her in the past month, since she opened her big mouth at the library about rescuing strays.

The kettle whistled and Katherine thought, damn.

*

"Hell's bells," Scrudde muttered as he watched Katherine approach.

"Katherine Reee-no," Coote said, faking the French and sticking out that fat tongue-tip.

The other two apparently knew her but Bear had never seen the woman before: hovering around thirty, average height, thin and straight, with thick red hair cut short, wide mouth, green eyes, and freckles; she looked a little scared and she wore an oversized corduroy coat and boots too big, an outfit that appeared to have been borrowed from a larger brother.

When Katherine reached the men she didn't know what to say; she had no authority here and it wasn't in her nature to berate people, yet when she saw the cow, suffering and bleeding, her face went red with anger. She looked now at Bear, holding the fork, and told him softly, "You should be ashamed of yourself."

He was appalled that she thought he was the one who put puncture holes in that cow. Bear wanted to explain. He's got the pitchfork because he'd taken it away from Coote. But Bear said nothing. He had three problems in life and one of them was happening right now: his mind in a muddle when emotions ran high and an explanation was needed.

Scrudde grinned that Bear was being falsely accused, but Coote, lacking Scrudde's instinct for the devious, came out and told Katie, "Bear's a big animal-lover like you, he was trying to stop us, is why he's got the fork."

Bear thought, thank you, Cootie, thank you for telling the truth.

Katherine was glad to hear it. She liked the looks of the big man, over six feet and over two hundred pounds but appearing to take up even more space than that because his shoulders were ax-handle broad and his chest barrel deep, neck thick and hands like big mitts made for a shovel. He had a wide, high-cheeked face that was lovely and open and round and innocent, soft blue eyes, a trimmed black goatee, and long black hair that he combed straight back and tied with a string. Unusual for a country man around here, he didn't wear an ounce of denim, neither jeans nor jacket, but instead had on a pair of worn gray dress pants, an old tweed jacket. He looked like he could've been an eccentric professor or funky jazz musician, maybe even an oversized poet. Katherine figured him at about her age or maybe a little older. She had a soft spot for oddballs; it was too bad this one stood there with his mouth hanging open because it made him appear moronic. (This was the second of Bear's three problems: forgetting to close his mouth.)

"My name is Katherine Renault," she said to Bear. "Kate."

Coote asked her, "Who told you we was out here, Kate? It was that school bus driver, wasn't it. I saw her slowing down when she went by."

"I'd rather not say -- "

Coote cut in, "It's all you women hanging out at that library, trying to cook up things to do with your time 'cause you ain't got to work or nothing." He let the wet tip of his tongue show and said, "I know about you women."

"What?"

Coote held two fingers, V for victory, to his mouth and obscenely worked that tongue in and out between those fingers.

Scrudde laughed.

Bear didn't get it.

Katherine was unsettled and remembered that she'd read once about tribal women who would, upon hearing the enemy approach, hurry down to water's edge and gather up sand and work it into their vaginas, packing themselves against the prospect of rape. It was said that when white soldiers came, the women learned to pack themselves front and back. Now Katherine thought that here in this hard country, maybe everywhere in the world, if a woman has to go out alone among men, she should start every day with sand.

She knew Scrudde and Coote, knew them from what the women at the library told her. Scrudde cheated people and mistreated his animals; he raised veal calves in the worst possible conditions. Coote beat up women and was capable of dragging Katherine back into the woods where they wouldn't be seen from the road, and Scrudde wouldn't try to stop him, Scrudde would be happy to watch. But Katherine didn't know the big man with the pitchfork, where he fit on the spectrum of what men will and won't do to a woman, and she turned to him now and asked his name.

Bear couldn't find a voice.

"He's Bear," Scrudde told her.

"Bear?" She stayed riveted on him. "Is that your last name?"

Coote laughed. "Bear's his nickname 'cause he shuffles like a big ol' bear, ain't that right, Bear?"

Bear didn't answer.

"Lives in that farm up the road there," Coote continued.

Katherine finally stopped looking at Bear and turned toward the younger man. "You're the one they call Cootie."

"Coot," he corrected her. "Carl Coot."

"I don't mean to interfere where it's not my business, but can you just tell me what's happening here, why this animal is being stuck with a pitchfork?"

Coote, disarmed by her soft manner, nodded toward Scrudde and said, "His cow."

All grease and grin, Scrudde told her, "We're trying to save this animal. She won't live unless she stands and she won't stand unless we force her to. If you knew anything about cows, you'd know that."

Before Katherine could reply, Coote said he knew a guaranteed way to get the cow to stand up. He went around gathering twigs and dry sticks. Oddly, perversely, he was doing this to impress the woman.

She didn't know what Coote intended but Bear did. He'd raised beef cattle all his life. On occasion he had forced cows to stand by shouting at them, pulling on their tails, kicking them in the ass. But stabbing them with a pitchfork was wrong and what Coote did now was even worse: lifting the cow's tail and piling kindling right there at her tender vulva, then leaning down with a butane lighter.

Watching Coote, the other three waited as the air around them acquired shoulders, tensed up for what might happen next.

"Hey, Bear," Coote asked as he took out a generic cigarette, lit it, then returned the butane flame to that pile of sticks, "you smoke?"

Bear didn't answer.

"Well, this cow don't know it but she's about to start smoking." He held the flame to the sticks until they ignited.

Katherine couldn't believe it, the cruelty of it. She stepped forward to put the flames out but was grabbed around the waist by Scrudde.

Then it was Bear who kicked away the fire.

And time got up on a bicycle.

Katherine held down on Scrudde's wrists to keep him away from her chest.

Coote cursed as he stood, throwing the cigarette from his mouth and making fists of both hands.

Scrudde waited there behind Katherine, excitement glistening in his eyes, he wanted to see a fight and sneak a feel when the woman struggled. But fists didn't get thrown and Katherine didn't struggle except to keep her hands firmly on Scrudde's wrists. He released her and said to the two men, squared off, "Now boys."

Coote cursed some more, then regathered the sticks and twigs, repiling them beneath the cow's tail, reigniting the tinder.

"Both of you," Scrudde said to Bear and Katherine as he positioned himself to keep them away from what Coote was doing to the downed animal, "this ain't your cow and this ain't your land."

For Bear it was a powerful argument here where men worshiped at the altar of private property.

But Katherine, recognizing a higher authority, asked Bear, "Are you going to let this happen?"

He threw down the pitchfork.

"If a little heat will cause this cow to stand," Scrudde continued in that oily voice he used when reading at church on Sundays and Wednesdays, "well, then, that's just a way of saving her life, any reasonable person would see it that way."

Coote was leaning over and blowing on the fire, burning quickly with everything so dry this time of year. "Smells like barbecue!" he shouted, standing with Scrudde to block interference.

These are black-hearted men, Bear thought, that's what Robert would call them. Robert was Bear's beloved older brother, and he had a way with words. Their father used to say Bear was born with the bulk, Robert with the brains. Robert got all A's in school and had so many girlfriends you couldn't keep track of them without a scorecard, also something their father used to say. Robert was normal size. Bear started as a big baby and kept on growing, reaching six feet and two hundred pounds barely into his teens. It was because this growth embarrassed him that he started to hunch his shoulders and walk with a lumbering gait, giving rise to his nickname, which in later years he didn't regret because it was a good name for someone bred by the forest's barely people.

The third of his three problems (along with his mind getting in a muddle at critical times and that propensity for mouth breathing) was inappropriate behavior, but whether Bear was officially retarded was a topic of some debate in the local town of Briars. He had dropped out of school when it was legal, age sixteen. He went to work full-time on the farm, just him and his father because the mother had run off years and years ago and then Robert left as soon as he could too, went to Chicago and got himself a big job.

The flames were terrible now, Coote adding fresh fuel. All four people could smell the flesh cooking and so could the suffering cow. Although her anal-genital area was being burned alive, she was still too weak to stand and could only endure, stretching her neck, moaning pitifully like a trombone played in hell, rolling her eyes to white, enduring this horror because that's all she could do, endure.

Even during the worst parts of her illness, the horrors of the operation, Katherine had stayed in control of her emotions, but now, as she watched that cow being burned alive, she went a little crazy and shouted for Coote and Scrudde to stop, please stop burning that poor animal, then she pleaded for Bear to do something.

Which he did, shoving the men aside and kicking out the fire.

Coote came around and got in a sucker punch. Bear grabbed him by the throat.

"Retard!" was all Coote managed to say before Bear squeezed, choking off further insult as Coote's tongue emerged in earnest now.

When Scrudde picked up the pitchfork and stabbed, Bear grabbed him by the neck and lifted both men off the ground, one in each hand, suspending them in death grips.

Time rode faster as Katherine watched wide-eyed. She considered herself equal to most men she'd met, perhaps their better in perception, in endurance, empathy, but she yielded to males in this one category: violence. Her roommate in college had a boyfriend who, in Katherine's presence, struck the roommate in the face with his fist -- which stunned Katherine who'd been raised in a gentle family and had never seen violence up close. Several times in the five months she'd lived here, Katherine had witnessed local men striking their wives or children in public. It was scary the way a man could transform from what appeared to be a normal father and husband into something so terribly ready to kill.

This man here, this Bear, blue eyes no longer soft, he clearly intended homicide. Lowering his victims to the ground to get better grips on their throats, he shook them and shook them, his hands like two terriers, Scrudde and Coote the rats. Both men tried desperately to escape Bear's grip as their faces turned a terrible purple and they voided their bladders, bulged their eyes.

I have to do something, Katherine thought, though she was already stepping backwards to put distance between herself and this man who was committing murder.

"They're not worth it," she said softly, retracing steps to place a gentle hand on Bear's left arm, the one he was using to power that choke hold on Phil Scrudde. (Katherine felt something amazing when she touched Bear: the big man was actually vibrating.)

As if coming out of a trance, Bear dropped them in a gasping heap, Scrudde atop Coote, then reached into his front left pocket and took out an immense folding knife, ten inches when open. "No," she said softly, Scrudde and Coote untangling from each other to shrink back in mortal fear.

Bear went around to the cow. Before slitting the animal's throat, he looked up at Katherine wanting to explain what he was doing, why he had to do it, but she already understood and nodded for him to go ahead.

When he made puncture-slits in two places on the neck, the cow jolted each time as if Bear's blade was connected to electricity. But it would take her another minute or so to die. Unlike horses and sheep, which are always rushing toward mortality, cows seem to get right up to the edge and then refuse to go over no matter the size of their suffering or the unlikeliness of their prospects.

While the cow was thus dying, Bear stood guard to make sure no more fires got started. Scrudde and Coote were on their feet, voices raw as Coote cursed Bear with terrible words and Scrudde called Bear a clay-eater.

Bear looked to the woman to see if she'd heard that slander, but the only thing on her freckled face was anguish for an animal's suffering.

He knelt down to see if it was over yet, covering the cow's closed eye with his hand, then pulling back her eyelid. That big brown eye fixed Bear and, just before dipping into oblivion, the cow told him, God bless you...and time stopped.

Copyright © 2002 by David Lozell Martin

Watch time. At 8:30 A.M. on April 19, a farmer named Joseph David Long, known locally as Bear, was on his way into town when he saw two men standing over a cow. Bear stopped his truck to the side of the county road and looked out across the pasture -- a fringe of grassland, a background of forest. Both men laughed. They were far enough away for him to see their heads go back before he heard their laughter, which came a disconnected moment later, as in a poorly dubbed movie. Bear knew that one of the men must be Phil Scrudde because Scrudde's big blue Cadillac was parked right out there in the pasture, next to the cow, which was lying down. Scrudde was famous for driving his Cadillac into pastures and fields, like maybe he thought he was Hud. From this distance, Bear couldn't recognize the other man, taller and thinner.

Quickly now, Scrudde, the shorter fatter man, grabbed up a pitchfork and stuck the cow's flank. Bear's mouth dropped at the sudden cruelty of it and he once again saw movement -- the cow stretching its neck and raising its muzzle at being impaled -- before hearing the cow's sound, a sad trumpet on this empty-stage, frost-chilled April morning. Bear exited his truck and crossed the fence.

More than a fence was crossed of course. To enter that pasture was one of those decisions fat with fate, leading to mayhem. But even if he'd known it at the time, Bear still would've crossed that fence: he was a dangerously uncomplicated man; on occasion he was inevitable.

When they saw him coming, Bear counting steps, Scrudde handed the pitchfork to the taller man, who turned out to be Carl Coote, twenty-five years old and considered handsome by the women. Carl preferred you hold the final e silent when pronouncing his last name, but it was a campaign he had waged without success from first grade on. Carl was called Cootie. He worked for Scrudde because no one else would have him, Carl known as a thief and fistfighter. Word was he wanted to be a rock star, though how he hoped to accomplish this, here in Appalachia, was anyone's guess.

"Hello there, Bear," Scrudde said with a smile like false dawn. "You're just the man we need." Scrudde had a problem with the pronunciation of his last name, too. He wanted you to call him "Scrud," rhymes with Hud and sounds tough, but people who did business with him pronounced it "Screwed," as in I have been...He was a sneaky little man, age fifty-six, who had acquired a fortune through deceit -- cheating widows, for example. He seldom attacked directly but was relentless on the back end of a deal, stabbing you with a lawyer if it came to that. In his younger days he'd been notorious as a dog-poisoner.

"Unless we get this cow to stand," Scrudde continued in that falsely jaunty voice, "she'll die for sure. Now, everybody knows Bear has a way with animals. You get her on her feet for us, what do you say?"

Bear looked down at the cow's rump and counted a dozen puncture wounds oozing thick dark blood. Bear counted things; he was also a name-giver.

"I'll get her up," Coote announced. He wore black jeans and a black cowboy shirt and an open letter-jacket from high school. At his skinny neck you could see the tops of chest tattoos. Coote stuck the cow with two short jabs of the pitchfork, adding six additional puncture wounds and eliciting from the creature another pained bellow.

Bear reached over and took the pitchfork from Coote, who started to protest but was interrupted by Scrudde telling Bear this was all the cow's fault. "No use trying to doctor 'em, Bear, unless you get 'em to stand first, you know that. This one's being contrary." Scrudde wore lizard cowboy boots, wool pants so thick they looked inflated, a denim jacket, and a white cowboy hat. All the other farmers around here called themselves farmers but Scrudde said he was a rancher.

"Gimme that fork back," Coote demanded.

Bear didn't.

As Coote weighed the issue, his tongue squeezed together until it was real fat and then the tip came out between his lips -- a lifelong tic. He was thin but ropy strong, long redneck hair greasy over the shirt collar, his face cut on angles and planes that caught light and cast shadows. Sometimes he played electric guitar with a garage band, more loud than good. Coote practiced sticking out his tongue onstage. He had eyes sleepy with luxury lashes and the lids halfway down, what the women called bedroom eyes, but many men took as insolence. In fact, those eyes and what he did with his tongue made some men want to slap his face on principle, which is what had turned the boy into a fistfighter.

Scrudde, seeing the two men weren't going to engage, at least not just yet, mocked the peacemaker by saying what's important here is not our petty differences, what's important here is saving this poor cow, God's creature. "Bear, can't you get her to stand? That'll save her life, you know it will, give me your opinion."

There was truth to it, a sick cow that's down and won't get up will surrender on the whole idea of living and before you can do any good with food or water or medication, first you got to get that cow on her feet.

Bear, still holding the pitchfork out of Coote's reach, bent to this particular cow, black with a white face, a cross between an Angus bull and a Hereford cow. She was old and had suffered a winter of low-quality hay and no supplemental grain, Scrudde squeezing a few cents more out of each pound of his cattle's flesh. This one was also in severe dehydration owing to the lateness of spring rains. With only a few pools of mud-fouled water in the creeks, cows didn't drink as much as they should. Bear knew that if you cut open this cow right now you'd find bushel baskets of crumbly dry feces blocking her bowels. New green grass could save her, could liquefy and clean her bowels, but it was April and the spring grass hadn't come in earnest yet.

"What'da you say, Bear?" Scrudde urged.

"Shoot her," was what Bear finally said...which surprised the other two because Bear seldom spoke. If you knew this, then pressing him to speak, as Scrudde had been doing, became a form of ridicule.

"Shoot her?" Scrudde took off his cowboy hat, used the inside of his forearm to wipe at his high white forehead, then replaced the hat. "That's fine advice coming from a animal-lover like you." This was not meant as a compliment. "Get her on her feet, she'll be fine."

Bear shook his head because sometimes a failure to stand is not a matter of lethargy or contrariness, sometimes the cow is all but dead but simply won't die, which was the case with this one.

"You wanna buy her?" Scrudde asked. "Everything I own is for sale at the right price, so if you want to buy this cow and save her your own way, let's dicker."

"Shoot her," Bear repeated. Shoot this cow and put her out of misery's reach. Bear had a revolver in his truck, Scrudde undoubtedly had one in that Cadillac there. Just shoot her.

"Company," Coote said.

Bear and Scrudde looked toward the road where another vehicle, an old green Chevy Nova, was parked facing Bear's truck. A woman had crossed the same fence as Bear and was heading toward the three men at a measured pace, almost as if she, like Bear, counted her steps.

*

At eight-thirty that morning, precisely the time Bear first stopped his truck to see what the men were doing with the cow, Katherine Renault had been awakened by a phone call.

"Hi, hope I didn't wake you."

"Who is this?"

"Don't you know? It's Barbara."

Barbara? Katherine had been living in this small town for five months and still wasn't accustomed to the reality that everyone knew her, the expectation that she should know everyone. Who was Barbara? Must be one of the women from the library.

"I did wake you, didn't I?"

Katherine looked at the bedside clock and lied, saying she'd been awake for hours. "What's up?"

Barbara drove a school bus and this morning had seen something nasty, two men sticking a cow with a pitchfork. She told Katherine where, exactly, on the bus route this had happened and said she hoped Katherine would go out there and make the men stop, it was a terrible thing to see.

"How can I make them stop?" Katherine asked, sitting up, wide awake now.

"At the library you were talking about rescuing animals."

"I meant strays, abandoned animals."

"Well that cow needs rescuing more than any stray, those men sticking it with a pitchfork."

Katherine asked why the men would be doing something like that.

Barbara said she didn't know and suggested Katherine go there and find out.

"Can you come with me?"

The woman said no, sorry, she was due back home to make breakfast for her husband. "This is more up your alley," she said. "You know, one of them rescue missions you were talking about."

Katherine started to explain again that she didn't mean rescuing animals from their owners, she meant rescuing strays and putting them up for adoption, but Barbara was already saying good-bye, hope you're able to do some good and save that cow, gotta go, I did my duty by telling you.

It was last year at Thanksgiving that Katherine Renault came here, moved into a little furnished cottage owned by her fiancé. He was always apologizing for owning property in the heart of Appalachia, explaining that he had inherited it from an uncle and decided to keep it as a vacation place, fix it up, diversifying his property portfolio. After Katherine's illness, after the operation, after she got out of the hospital, when she started going crazy because all her friends were so constantly there, doing what friends are supposed to do, offering advice and comfort and company, what Katherine most wanted in the world was some time alone. So her fiancé offered his little hillbilly cottage, as he called it, and Katherine came here intending to stay a few weeks. It had been five months.

Here, people left her alone. Katherine was the one who finally made contact after going stir-crazy, too much TV. She started taking walks around town, seeing notices about meetings at the library: book groups, civic improvement, self-esteem, weight loss. It was at one of the library meetings, attended by women and a few old men, that Katherine mentioned rescuing stray animals. For the last eight years she'd worked as a lobbyist in Washington, D.C., representing nonprofit fund-raising organizations, but before that, back when she got out of college, Katherine had volunteered with groups like Greenpeace and PETA -- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. A person would have to be careful about mentioning animal rights here, Katherine thought -- here in Appalachian farm country where animals are considered personal property, where violence is commonplace and farmers go armed in their fields. Katherine was interested in finding homes for strays, nothing more than that; she was here only temporarily, would be going back to D.C. soon and getting married.

She got out of bed, washed, dressed, and wondered how to approach men who were torturing a cow, what to say to them. Back in D.C., in Katherine's circles, a woman could say something wiseass or provocative to a man, he'd laugh and think the woman was great fun. But not here. Katherine had seen how men here reacted when a woman was smart-alecky, acted flippant or defiant; men would get their backs up and give the woman a bad look under bristly eyes that warned her, you'd better watch your mouth.

Katherine didn't want any part of that throwback behavior. She was here to recover, recuperate, then go home.

Heating water for tea, Katherine watched the two parrots she was caring for as they sidestepped back and forth the lengths of their perches. Outside in the fenced yard, eight dogs were awakening, stretching, walking the perimeter. All these animals had come to her in the past month, since she opened her big mouth at the library about rescuing strays.

The kettle whistled and Katherine thought, damn.

*

"Hell's bells," Scrudde muttered as he watched Katherine approach.

"Katherine Reee-no," Coote said, faking the French and sticking out that fat tongue-tip.

The other two apparently knew her but Bear had never seen the woman before: hovering around thirty, average height, thin and straight, with thick red hair cut short, wide mouth, green eyes, and freckles; she looked a little scared and she wore an oversized corduroy coat and boots too big, an outfit that appeared to have been borrowed from a larger brother.

When Katherine reached the men she didn't know what to say; she had no authority here and it wasn't in her nature to berate people, yet when she saw the cow, suffering and bleeding, her face went red with anger. She looked now at Bear, holding the fork, and told him softly, "You should be ashamed of yourself."

He was appalled that she thought he was the one who put puncture holes in that cow. Bear wanted to explain. He's got the pitchfork because he'd taken it away from Coote. But Bear said nothing. He had three problems in life and one of them was happening right now: his mind in a muddle when emotions ran high and an explanation was needed.

Scrudde grinned that Bear was being falsely accused, but Coote, lacking Scrudde's instinct for the devious, came out and told Katie, "Bear's a big animal-lover like you, he was trying to stop us, is why he's got the fork."

Bear thought, thank you, Cootie, thank you for telling the truth.

Katherine was glad to hear it. She liked the looks of the big man, over six feet and over two hundred pounds but appearing to take up even more space than that because his shoulders were ax-handle broad and his chest barrel deep, neck thick and hands like big mitts made for a shovel. He had a wide, high-cheeked face that was lovely and open and round and innocent, soft blue eyes, a trimmed black goatee, and long black hair that he combed straight back and tied with a string. Unusual for a country man around here, he didn't wear an ounce of denim, neither jeans nor jacket, but instead had on a pair of worn gray dress pants, an old tweed jacket. He looked like he could've been an eccentric professor or funky jazz musician, maybe even an oversized poet. Katherine figured him at about her age or maybe a little older. She had a soft spot for oddballs; it was too bad this one stood there with his mouth hanging open because it made him appear moronic. (This was the second of Bear's three problems: forgetting to close his mouth.)

"My name is Katherine Renault," she said to Bear. "Kate."

Coote asked her, "Who told you we was out here, Kate? It was that school bus driver, wasn't it. I saw her slowing down when she went by."

"I'd rather not say -- "

Coote cut in, "It's all you women hanging out at that library, trying to cook up things to do with your time 'cause you ain't got to work or nothing." He let the wet tip of his tongue show and said, "I know about you women."

"What?"

Coote held two fingers, V for victory, to his mouth and obscenely worked that tongue in and out between those fingers.

Scrudde laughed.

Bear didn't get it.

Katherine was unsettled and remembered that she'd read once about tribal women who would, upon hearing the enemy approach, hurry down to water's edge and gather up sand and work it into their vaginas, packing themselves against the prospect of rape. It was said that when white soldiers came, the women learned to pack themselves front and back. Now Katherine thought that here in this hard country, maybe everywhere in the world, if a woman has to go out alone among men, she should start every day with sand.

She knew Scrudde and Coote, knew them from what the women at the library told her. Scrudde cheated people and mistreated his animals; he raised veal calves in the worst possible conditions. Coote beat up women and was capable of dragging Katherine back into the woods where they wouldn't be seen from the road, and Scrudde wouldn't try to stop him, Scrudde would be happy to watch. But Katherine didn't know the big man with the pitchfork, where he fit on the spectrum of what men will and won't do to a woman, and she turned to him now and asked his name.

Bear couldn't find a voice.

"He's Bear," Scrudde told her.

"Bear?" She stayed riveted on him. "Is that your last name?"

Coote laughed. "Bear's his nickname 'cause he shuffles like a big ol' bear, ain't that right, Bear?"

Bear didn't answer.

"Lives in that farm up the road there," Coote continued.

Katherine finally stopped looking at Bear and turned toward the younger man. "You're the one they call Cootie."

"Coot," he corrected her. "Carl Coot."

"I don't mean to interfere where it's not my business, but can you just tell me what's happening here, why this animal is being stuck with a pitchfork?"

Coote, disarmed by her soft manner, nodded toward Scrudde and said, "His cow."

All grease and grin, Scrudde told her, "We're trying to save this animal. She won't live unless she stands and she won't stand unless we force her to. If you knew anything about cows, you'd know that."

Before Katherine could reply, Coote said he knew a guaranteed way to get the cow to stand up. He went around gathering twigs and dry sticks. Oddly, perversely, he was doing this to impress the woman.

She didn't know what Coote intended but Bear did. He'd raised beef cattle all his life. On occasion he had forced cows to stand by shouting at them, pulling on their tails, kicking them in the ass. But stabbing them with a pitchfork was wrong and what Coote did now was even worse: lifting the cow's tail and piling kindling right there at her tender vulva, then leaning down with a butane lighter.

Watching Coote, the other three waited as the air around them acquired shoulders, tensed up for what might happen next.

"Hey, Bear," Coote asked as he took out a generic cigarette, lit it, then returned the butane flame to that pile of sticks, "you smoke?"

Bear didn't answer.

"Well, this cow don't know it but she's about to start smoking." He held the flame to the sticks until they ignited.

Katherine couldn't believe it, the cruelty of it. She stepped forward to put the flames out but was grabbed around the waist by Scrudde.

Then it was Bear who kicked away the fire.

And time got up on a bicycle.

Katherine held down on Scrudde's wrists to keep him away from her chest.

Coote cursed as he stood, throwing the cigarette from his mouth and making fists of both hands.

Scrudde waited there behind Katherine, excitement glistening in his eyes, he wanted to see a fight and sneak a feel when the woman struggled. But fists didn't get thrown and Katherine didn't struggle except to keep her hands firmly on Scrudde's wrists. He released her and said to the two men, squared off, "Now boys."

Coote cursed some more, then regathered the sticks and twigs, repiling them beneath the cow's tail, reigniting the tinder.

"Both of you," Scrudde said to Bear and Katherine as he positioned himself to keep them away from what Coote was doing to the downed animal, "this ain't your cow and this ain't your land."

For Bear it was a powerful argument here where men worshiped at the altar of private property.

But Katherine, recognizing a higher authority, asked Bear, "Are you going to let this happen?"

He threw down the pitchfork.

"If a little heat will cause this cow to stand," Scrudde continued in that oily voice he used when reading at church on Sundays and Wednesdays, "well, then, that's just a way of saving her life, any reasonable person would see it that way."

Coote was leaning over and blowing on the fire, burning quickly with everything so dry this time of year. "Smells like barbecue!" he shouted, standing with Scrudde to block interference.

These are black-hearted men, Bear thought, that's what Robert would call them. Robert was Bear's beloved older brother, and he had a way with words. Their father used to say Bear was born with the bulk, Robert with the brains. Robert got all A's in school and had so many girlfriends you couldn't keep track of them without a scorecard, also something their father used to say. Robert was normal size. Bear started as a big baby and kept on growing, reaching six feet and two hundred pounds barely into his teens. It was because this growth embarrassed him that he started to hunch his shoulders and walk with a lumbering gait, giving rise to his nickname, which in later years he didn't regret because it was a good name for someone bred by the forest's barely people.

The third of his three problems (along with his mind getting in a muddle at critical times and that propensity for mouth breathing) was inappropriate behavior, but whether Bear was officially retarded was a topic of some debate in the local town of Briars. He had dropped out of school when it was legal, age sixteen. He went to work full-time on the farm, just him and his father because the mother had run off years and years ago and then Robert left as soon as he could too, went to Chicago and got himself a big job.

The flames were terrible now, Coote adding fresh fuel. All four people could smell the flesh cooking and so could the suffering cow. Although her anal-genital area was being burned alive, she was still too weak to stand and could only endure, stretching her neck, moaning pitifully like a trombone played in hell, rolling her eyes to white, enduring this horror because that's all she could do, endure.

Even during the worst parts of her illness, the horrors of the operation, Katherine had stayed in control of her emotions, but now, as she watched that cow being burned alive, she went a little crazy and shouted for Coote and Scrudde to stop, please stop burning that poor animal, then she pleaded for Bear to do something.

Which he did, shoving the men aside and kicking out the fire.

Coote came around and got in a sucker punch. Bear grabbed him by the throat.

"Retard!" was all Coote managed to say before Bear squeezed, choking off further insult as Coote's tongue emerged in earnest now.

When Scrudde picked up the pitchfork and stabbed, Bear grabbed him by the neck and lifted both men off the ground, one in each hand, suspending them in death grips.

Time rode faster as Katherine watched wide-eyed. She considered herself equal to most men she'd met, perhaps their better in perception, in endurance, empathy, but she yielded to males in this one category: violence. Her roommate in college had a boyfriend who, in Katherine's presence, struck the roommate in the face with his fist -- which stunned Katherine who'd been raised in a gentle family and had never seen violence up close. Several times in the five months she'd lived here, Katherine had witnessed local men striking their wives or children in public. It was scary the way a man could transform from what appeared to be a normal father and husband into something so terribly ready to kill.

This man here, this Bear, blue eyes no longer soft, he clearly intended homicide. Lowering his victims to the ground to get better grips on their throats, he shook them and shook them, his hands like two terriers, Scrudde and Coote the rats. Both men tried desperately to escape Bear's grip as their faces turned a terrible purple and they voided their bladders, bulged their eyes.

I have to do something, Katherine thought, though she was already stepping backwards to put distance between herself and this man who was committing murder.

"They're not worth it," she said softly, retracing steps to place a gentle hand on Bear's left arm, the one he was using to power that choke hold on Phil Scrudde. (Katherine felt something amazing when she touched Bear: the big man was actually vibrating.)

As if coming out of a trance, Bear dropped them in a gasping heap, Scrudde atop Coote, then reached into his front left pocket and took out an immense folding knife, ten inches when open. "No," she said softly, Scrudde and Coote untangling from each other to shrink back in mortal fear.

Bear went around to the cow. Before slitting the animal's throat, he looked up at Katherine wanting to explain what he was doing, why he had to do it, but she already understood and nodded for him to go ahead.

When he made puncture-slits in two places on the neck, the cow jolted each time as if Bear's blade was connected to electricity. But it would take her another minute or so to die. Unlike horses and sheep, which are always rushing toward mortality, cows seem to get right up to the edge and then refuse to go over no matter the size of their suffering or the unlikeliness of their prospects.

While the cow was thus dying, Bear stood guard to make sure no more fires got started. Scrudde and Coote were on their feet, voices raw as Coote cursed Bear with terrible words and Scrudde called Bear a clay-eater.

Bear looked to the woman to see if she'd heard that slander, but the only thing on her freckled face was anguish for an animal's suffering.

He knelt down to see if it was over yet, covering the cow's closed eye with his hand, then pulling back her eyelid. That big brown eye fixed Bear and, just before dipping into oblivion, the cow told him, God bless you...and time stopped.

Copyright © 2002 by David Lozell Martin