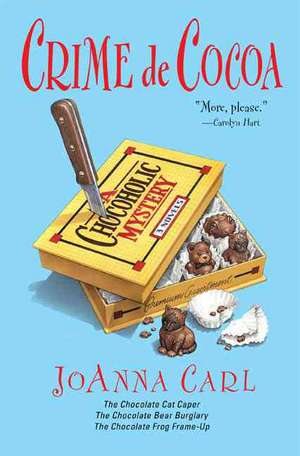

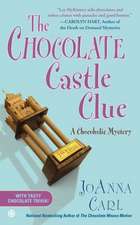

Crime de Cocoa: Chocoholic Mysteries

Autor JoAnna Carlen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2005

Preț: 136.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.08€ • 28.32$ • 21.91£

26.08€ • 28.32$ • 21.91£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780451216946

ISBN-10: 0451216946

Pagini: 501

Dimensiuni: 154 x 231 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: New American Library

Seria Chocoholic Mysteries

ISBN-10: 0451216946

Pagini: 501

Dimensiuni: 154 x 231 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: New American Library

Seria Chocoholic Mysteries

Notă biografică

JoAnna Carl is the pseudonym of a multipublished mystery writer. She spent more than twenty-five years in the newspaper business, working as a reporter, feature writer, editor and columnist. She holds a degree in journalism from the University of Oklahoma and also studied in the OU Professional Writing Program. She lives in Oklahoma but spends much of her summer at a cottage on Lake Michigan near several communities similar to the fictional town of Warner Pier.

Extras

Excerpt from Chapter 1

People thing working in a resort town is like long vacation. And it might be, if the tourists would only stay at home.

I stood behind the counter of TenHuis Chocolade (“Handmade chocolates in the Dutch tradition”) and hated the girl on the other side. I’d been working for my aunt and uncle, Nettie and Phil TenHuis, for only a week, and this girl had been in every day, apparently with the sole objective of ruining my life.

Her name, according to her credit card, was Alana Fairchild Hyden. She would have been pretty if she hadn’t been so thin. She was about my age ߝ which was sixteen that year ߝ and she had dark hair and big brown eyes, which she emphasized with liner, mascara, and shadow until they dominated her face.

Alana Fairchild Hyden was about the only teenaged customer TenHuis Chocolade ever drew, since Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil’s candy wasn’t the kind you’d eat in the movies. Oh, they had some inexpensive items, like a milk chocolate sailboat on a stick, but most of their stock was luxury chocolates and fancy dipped fruits. One bonbon cost as much as two Hershey bars.

But Alana Fairchild Hyden came in every day and bought half a pound of bonbons and truffles, a different assortment every day. She did this, I’d decided, to torture me. She got this smirk on her face, and she went through the whole display case, pointing.

“Now what’s that one?”

Since I was new, I’d have to consult the list. “Creamy, European-style caramel in dark chocolate.”

“How about the one behind it?”

I’d look at the list again. “Raspberry cream.”

“No, the one with the yellow dot.”

“Lemon canache.”

“Yuk! How about the white chocolate with the little nutty things on top?”

That one I knew, because it was my favorite. “Amadeus,” I said. Then I winced. She’d goaded me until I was nervous, and that was when my tongue twisted itself into knots and the wrong word came out. “I mean, Amaretto.”

Of course, Alana Fairchild Hyden laughed. “’Amadeus’! How funny! How about the one at the back of that row?”

Back to the list. “Frangelico.”

“Frangelico? Just what the hell is that?”

“I’ll ask.” I turned toward the big window that overlooked the sparkling white room where middle-aged women in white aprons and hair nets produced the chocolates.

“Oh, never mind! You’d think people would train their employees. Give me four of the fudgy ones and four square ones with the white centers. Then I’ll have eight of the dark chocolate balls. The rummy ones.”

Seeting, I put her chocolates ߝ four double fudge and four Bailey’s irsh Cream bonbons and eight Jamaican rum truffles ߝ in a little white box with “TenHuis Chocolade” in the corner in classy type, and I tired the box with a blue ribbon. I ran her credit card through the imprinter, then pushed the receipt and the card across the counter.

“Here’s your crevasse card.” I tried to pretend I’d said it right, but Alana Fairchild Hyden laughed.

“You are such a sketch!” she said. I tried to look blank. Pleasant would have been more than I could manage. She went out, still laughing, leaving the shop empty, except for the other clerk, Lindy Bradford, and me.

“What a bitch,” Lindy said.

I felt crushed, as well as angry. Alana Fairchild Hyden completely destroyed my confidence. It’s just a stupid sales clerk job, I told myself, and I can’t do it right because I can’t talk like a normal person.

“Don’t worry about it, Lee,” Lindy said. “She acts rude just to cover up her own inferiority complex.”

I gulped hard and decided it was safe to talk. “Who is she?”

“Oh, she’s one of the Hydens. They have that big house at the lake end of Orchard Street. Her grandfather made his money building airplanes. My mother says her mother is trying to spend every cent her grandfather ever made. They’re summer people.”

In the week I’d been working at TenHuis Chocolade, I’d discovered there were three social classes in Warner Pier ߝ locals, summer people, and tourists. Locals either lived there year-round, or they owned businesses there and spent most of the year in the area. Summer people owned homes ߝ what us Texans would call “cabins,” but what these Michigan people called “cottages” ߝ and spent several months there each year. Tourists came for periods ranging from a day to a month and rented rooms in the motels, inns, or bed and breakfasts.

So Alana Fairchild Hyden was a “summer person,” not a “tourist.” I sighed. “I guess shell be in every day until I leave in August.”

“Who knows?” Lindy reached into the showcase and straightened the Italian cherry creams. “I feel kinda sorry for her, I guess. She always comes in alone.” She shot me a sidelong glance. “Hey, three of us are going into Holland to the late show tonight. Ask your uncle if you can come. We’ll be home by twelve-thirty.”

“Not tonight,” I said, “But thanks.” Luckily, three people came in right then. I couldn’t tell if they were tourists or summer people, but I was glad for the distraction. Not that I didn’t appreciate Lindy acting friendly. I just wasn’t ready to be friendly back. While Lindy told the new customers that we didn’t carry candy bars, I stood there miserably and wished I was on the beach. Alone. Without the bag lady I’d seen that morning.

The beach was the best place to cry. That’s why I resented sharing it, especially with a bag lady.

The bag lady scared me. She looked like a homeless old hag, the kind you might see under a bridge in a big city. I hadn’t expected to run into someone like that on a Lake Michigan beach, down the road from Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil’s house.

I kept telling myself she was harmless. But I still resented her. As I said ߝ the beach was the best place I had to cry, and I didn’t want to meet anybody.

For one thing, I had always loved the Texas plains. I was used to lots of sky, and Michigan’s tall trees made me feel closed in and choked up. But from the beach I could see Lake Michigan stretching west to somewhere beyond the horizon, and it was easier to breathe.

But all I wanted to do down there was sit behind a clump of beach grass and let the tears roll. I had a lot to cry about that summer. I’d lost my family and my friends and had been exiled to work in a chocolate factory.

My privacy had gone at the same time. Now I was living with my Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil, and the walls of their house ߝ which had been built in 1904 ߝ were too thin to hide sniffling. If I cried in bed at night, Aunt Nettie would creep upstairs to be sympathetic. If I declined her sympathy ߝ after all, she was almost a stranger to me- they sat downstairs and talked about how unhappy I was. I could hear every word. Why couldn’t they leave me alone?

People thing working in a resort town is like long vacation. And it might be, if the tourists would only stay at home.

I stood behind the counter of TenHuis Chocolade (“Handmade chocolates in the Dutch tradition”) and hated the girl on the other side. I’d been working for my aunt and uncle, Nettie and Phil TenHuis, for only a week, and this girl had been in every day, apparently with the sole objective of ruining my life.

Her name, according to her credit card, was Alana Fairchild Hyden. She would have been pretty if she hadn’t been so thin. She was about my age ߝ which was sixteen that year ߝ and she had dark hair and big brown eyes, which she emphasized with liner, mascara, and shadow until they dominated her face.

Alana Fairchild Hyden was about the only teenaged customer TenHuis Chocolade ever drew, since Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil’s candy wasn’t the kind you’d eat in the movies. Oh, they had some inexpensive items, like a milk chocolate sailboat on a stick, but most of their stock was luxury chocolates and fancy dipped fruits. One bonbon cost as much as two Hershey bars.

But Alana Fairchild Hyden came in every day and bought half a pound of bonbons and truffles, a different assortment every day. She did this, I’d decided, to torture me. She got this smirk on her face, and she went through the whole display case, pointing.

“Now what’s that one?”

Since I was new, I’d have to consult the list. “Creamy, European-style caramel in dark chocolate.”

“How about the one behind it?”

I’d look at the list again. “Raspberry cream.”

“No, the one with the yellow dot.”

“Lemon canache.”

“Yuk! How about the white chocolate with the little nutty things on top?”

That one I knew, because it was my favorite. “Amadeus,” I said. Then I winced. She’d goaded me until I was nervous, and that was when my tongue twisted itself into knots and the wrong word came out. “I mean, Amaretto.”

Of course, Alana Fairchild Hyden laughed. “’Amadeus’! How funny! How about the one at the back of that row?”

Back to the list. “Frangelico.”

“Frangelico? Just what the hell is that?”

“I’ll ask.” I turned toward the big window that overlooked the sparkling white room where middle-aged women in white aprons and hair nets produced the chocolates.

“Oh, never mind! You’d think people would train their employees. Give me four of the fudgy ones and four square ones with the white centers. Then I’ll have eight of the dark chocolate balls. The rummy ones.”

Seeting, I put her chocolates ߝ four double fudge and four Bailey’s irsh Cream bonbons and eight Jamaican rum truffles ߝ in a little white box with “TenHuis Chocolade” in the corner in classy type, and I tired the box with a blue ribbon. I ran her credit card through the imprinter, then pushed the receipt and the card across the counter.

“Here’s your crevasse card.” I tried to pretend I’d said it right, but Alana Fairchild Hyden laughed.

“You are such a sketch!” she said. I tried to look blank. Pleasant would have been more than I could manage. She went out, still laughing, leaving the shop empty, except for the other clerk, Lindy Bradford, and me.

“What a bitch,” Lindy said.

I felt crushed, as well as angry. Alana Fairchild Hyden completely destroyed my confidence. It’s just a stupid sales clerk job, I told myself, and I can’t do it right because I can’t talk like a normal person.

“Don’t worry about it, Lee,” Lindy said. “She acts rude just to cover up her own inferiority complex.”

I gulped hard and decided it was safe to talk. “Who is she?”

“Oh, she’s one of the Hydens. They have that big house at the lake end of Orchard Street. Her grandfather made his money building airplanes. My mother says her mother is trying to spend every cent her grandfather ever made. They’re summer people.”

In the week I’d been working at TenHuis Chocolade, I’d discovered there were three social classes in Warner Pier ߝ locals, summer people, and tourists. Locals either lived there year-round, or they owned businesses there and spent most of the year in the area. Summer people owned homes ߝ what us Texans would call “cabins,” but what these Michigan people called “cottages” ߝ and spent several months there each year. Tourists came for periods ranging from a day to a month and rented rooms in the motels, inns, or bed and breakfasts.

So Alana Fairchild Hyden was a “summer person,” not a “tourist.” I sighed. “I guess shell be in every day until I leave in August.”

“Who knows?” Lindy reached into the showcase and straightened the Italian cherry creams. “I feel kinda sorry for her, I guess. She always comes in alone.” She shot me a sidelong glance. “Hey, three of us are going into Holland to the late show tonight. Ask your uncle if you can come. We’ll be home by twelve-thirty.”

“Not tonight,” I said, “But thanks.” Luckily, three people came in right then. I couldn’t tell if they were tourists or summer people, but I was glad for the distraction. Not that I didn’t appreciate Lindy acting friendly. I just wasn’t ready to be friendly back. While Lindy told the new customers that we didn’t carry candy bars, I stood there miserably and wished I was on the beach. Alone. Without the bag lady I’d seen that morning.

The beach was the best place to cry. That’s why I resented sharing it, especially with a bag lady.

The bag lady scared me. She looked like a homeless old hag, the kind you might see under a bridge in a big city. I hadn’t expected to run into someone like that on a Lake Michigan beach, down the road from Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil’s house.

I kept telling myself she was harmless. But I still resented her. As I said ߝ the beach was the best place I had to cry, and I didn’t want to meet anybody.

For one thing, I had always loved the Texas plains. I was used to lots of sky, and Michigan’s tall trees made me feel closed in and choked up. But from the beach I could see Lake Michigan stretching west to somewhere beyond the horizon, and it was easier to breathe.

But all I wanted to do down there was sit behind a clump of beach grass and let the tears roll. I had a lot to cry about that summer. I’d lost my family and my friends and had been exiled to work in a chocolate factory.

My privacy had gone at the same time. Now I was living with my Aunt Nettie and Uncle Phil, and the walls of their house ߝ which had been built in 1904 ߝ were too thin to hide sniffling. If I cried in bed at night, Aunt Nettie would creep upstairs to be sympathetic. If I declined her sympathy ߝ after all, she was almost a stranger to me- they sat downstairs and talked about how unhappy I was. I could hear every word. Why couldn’t they leave me alone?