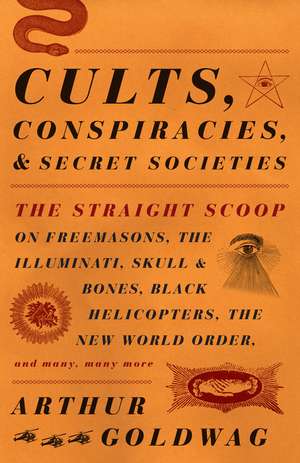

Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies: The Straight Scoop on Freemasons, the Illuminati, Skull and Bones, Black Helicopters, the New World Order,

Autor Arthur Goldwagen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

• Freemasonry's first American lodge included a young Benjamin Franklin among its members.

• The Knights Templar began as impoverished warrior monks then evolved into bankers.

• Groom Lake, Dreamland, Homey Airport, Paradise Ranch, The Farm, Watertown Strip, Red Square, “The Box,” are all names for Area 51.

An indispensable guide, Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies connects the dots and sets the record straight on a host of greedy gurus and murderous messiahs, crepuscular cabals and suspicious coincidences. Some topics are familiar—the Kennedy assassinations, the Bilderberg Group, the Illuminati, the People's Temple and Heaven's Gate—and some surprising, like Oulipo, a select group of intellectuals who created wild formulas for creating literary masterpieces, and the Chauffeurs, an eighteenth-century society of French home invaders, who set fire to their victims' feet.

Preț: 102.90 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 154

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.69€ • 20.48$ • 16.50£

19.69€ • 20.48$ • 16.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 februarie-07 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307390677

ISBN-10: 0307390675

Pagini: 332

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307390675

Pagini: 332

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Arthur Goldwag is the author of Isms and Ologies. A freelance writer and editor for more than twenty years, he has worked at Book-of-the-Month Club (where he created Traditions, a club devoted to Jewish interests), as well as at Random House and The New York Review of Books.

Extras

CULTS

What Makes a Cult Cultish?

The dictionary defines "cult" as a system of worship, but the word is usually used to denote a religious movement that is out of the mainstream. Christianity, for example, began as a cultic offshoot of Judaism, enjoying a similar status to the Essenes, the desert-dwelling ascetics who preserved the Dead Sea Scrolls, or the Samaritans, who not only belonged to a different ethnicity than the ancient Hebrews, but also didn't worship in the Temple in Jerusalem or acknowledge any but the first five books of the Bible. If a cult gains enough adherents, cultural currency, money, and other appurtenances of respectability, it generally becomes either a recognized denomination of the orthodoxy that spawned it or a full-fledged religion in its own right.

When members of one of those orthodoxies use the word "cult," more often than not they are using it pejoratively, to undercut a disreputably heterodox challenge to their own authority. Many evangelical Christians, for example, dismiss even such large, established movements as the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Church of Christ Scientist, and the Latter-Day Saints as cults, refusing to grant them the status of legitimate Christian denominations. On May 11, 2007, televangelist Bill Keller sent the following message about then-presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts and a practicing Mormon, to the millions of subscribers to his daily Internet devotional, "LivePrayer":

Romney winning the White House will lead millions of people into the Mormon cult. Those who follow the false teachings of this cult, believe in the false Jesus of the Mormon cult and reject faith in the one true Jesus of the Bible, will die and spend eternity in hell.

Although my tone may be snarky at times, I strive to be agnostic when it comes to the tenets and doctrines of the movements I describe in these pages. Though I have occasionally given in to the temptation to write about a group merely because its ideas are entertainingly strange (a la Koreshanity), I am much more interested in the power relations between the leadership of a group and its members than I am in its doctrines. For the most part, when I characterize a group as a cult I am using the word as a social scientist or a psychologist would, to denote a coercive or totalizing relationship between a dominating leader and his or her unhealthily dependent followers. What makes a cult cultish is not so much what it espouses, but how much authority its leaders grant themselves--and how slavishly devoted to them its followers are.

On February 25, 2009, the Supreme Court issued its judgment in Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum. Summum is a tiny sect founded in 1975 by Claude Nowell (1944-2008)--aka Corky King, Corky Ra, and Summum Bonum Amon Ra--whose members, among other things, mummify their pets and themselves after they die. A statue of the Ten Commandments stands in one of Pleasant Grove's public parks. Summum members wanted to erect a monument of their own commemorating their Seven Aphorisms* (according to Nowell's teachings, the aphorisms were inscribed on the tablets Moses smashed after his first descent from Mount Sinai; he received the Ten Commandments during his second ascent). Not surprisingly, Pleasant Grove did not wish to accommodate them, and the Supreme Court agreed that the city does not need to. Obviously Summum is more than a little weird by conventional standards--though Nowell claimed to have channeled his revelations from otherworldly beings, the theology he developed appears to be a hodgepodge of Masonic mysteries, Christian Gnosticism, and kitsch Egyptology--but it is not abusive or controlling and hence it does not fall under my rubric of "cult." Neither do the many iterations of Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Wicca, neo-paganism, Swedenborgianism, and many other occult, esoteric, and New Age movements that the Evangelicalist Web site Cultwatch devotes so much of its attention to.

Robert Lifton, the distinguished psychologist and author of such well-known books as The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (1986) and Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of "Brainwashing" in China (1961), defined cults in a 1981 article in the Harvard Mental Health Letter as an "aspect of a worldwide epidemic of ideological totalism, or fundamentalism." Cults, he continued, can be identified by three characteristics: 1) a charismatic leader "who increasingly becomes an object of worship"; 2) a process of "coercive persuasion or thought reform" (brainwashing, in other words); and 3) economic, sexual, or psychological exploitation of the rank-and-file members by the cult's leadership. The chief tool of "coercive persuasion," Lifton writes, is "milieu control; the control of all communication within a given environment."

Scientology has been accused of exploiting its acolytes and threatening its apostates, as has the Unification Church (its mass celebrations of arranged weddings, presided over by its founder and leader, Sun Myung Moon, epitomize the infringements of privacy and personal autonomy that so often go hand in glove with cult membership). Stephen Hassan, an ex-Moonie and an "exit counselor" for former cult members, defines a cult as a:

Pyramid-structured, authoritarian group or relationship where deception, recruitment, and mind control are used to keep people dependent and obedient. A cult can be a very small group or it can contain a whole country. The emphasis of mind control is what I call the BITE model: the control of behavior, information, thoughts, and emotions.

The Latter-Day Saints may be big enough and mainstream enough today to qualify as a religion, but many of the unaffiliated polygamous sects that style themselves as fundamentalist Mormons fit Lifton's and Hassan's definitions of a cult to a T, in that their leaders assume Godlike powers at the expense of their followers' autonomy and individuality. Alma Dayer LeBaron (1886-1951) led his polygamous followers to Mexico in the 1920s when he started his breakaway sect, the Church of the Lamb of God; over the next eighty years his sons Ervil, Joel, and Verlan fought bloodily over the succession, as did the fratricidal generation that followed theirs. While they carried on the family business of writing visionary screeds and murdering anyone who challenged their authority, they put their child brides and neglected children to work stealing cars, dealing drugs, and fencing stolen goods. Warren Jeffs, who succeeded his father, Rulon Jeffs (1909-2002), as President and Prophet, Seer and Revelator of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, has been convicted of "accomplice rape" for forcing minors into marriage.

Of course renegade Mormons don't have a monopoly on this sort of egregious behavior. A Hasidic rebbe who demands that his disciples submit every aspect of their personal and financial lives for his approval can justly be accused of cultism. The Armenian-Greek mystic G.I. Gurdjieff (1866?-1945) wrote books, composed music, and choreographed dances; his Fourth Way, an eclectic spiritual discipline which seeks to awaken the body, mind, and emotions, continues today under the auspices of the international Gurdjieff Society. But in his lifetime, he led a cult of personality; he was notoriously cruel and demanding to his students, who unreservedly gave themselves up to his power. His charisma was said to be so intense that he could cause a woman to have an orgasm just by looking at her across a room. 1 Mind Ministries, a tiny group led by a woman who calls herself Queen Antoinette, made headlines during the summer of 2008 when it was discovered that the one-year-old child of a member had been starved to death because he refused to say "amen."

A cult needn't be religious, either. The dancer Olgivanna Hinzenberg, one of Gurdjieff's disciples, married the architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). Wright's Taliesin school of architecture, where young architectural students performed virtual slave labor for the chance to learn from the master, had intensely cultish aspects to it. As Hassan notes, a whole country can devolve into cultishness--one need only think of Hitler's infamous Nuremberg rallies, Maoism at the height of China's Cultural Revolution, or the cult of personality surrounding Kim Jong Il, North Korea's "Dear Leader." A global, multilevel marketing concern like Amway, whose entrepreneurial leaders relentlessly pressure its salesmen to comport with their wider philosophy, to conform to their standards of success, to purchase only their approved products, and to associate only with their fellow Amway representatives, is no less cultic in some essential respects than the True Russian Orthodox Church, led by a schizophrenic named Pyotr Kuznetsov, whose thirty-some-odd members holed up in a cave in the Penza region of Central Russia in late 2007 to await the end of the world.

Then there are the cults of personality that grew up around supposed flying saucer contactees. George Adamski (1891-1965) was a self-proclaimed teacher of Tibetan wisdom and a would-be science fiction writer until he announced that he had been contacted by a Venusian named Orthon who told him about the dangers of nuclear war. Later he was taken for a ride in a flying saucer--adventures he recounted in his books Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953) and Inside the Spaceships (1955). Billy Meier is an ex-farmer from Switzerland who says he has been in communion with astronauts from the Pleiades star cluster since he was five years old. Thanks to their instruction, Meier says, he has achieved "the highest degree of spiritual evolution of any human being on earth." Though neither man had mass followings or required their disciples to worship them, the "nonprofit" foundations that they founded handsomely supported their various endeavors.

Mystical practice--whether in Buddhism, Hinduism, Sufism, Kabbalism, or the ecstatic Christianity of Meister Eckehart, Saint John of the Cross, and Teresa of Avila--is the pursuit of egolessness. Yoga and meditation are one means of dissolving the barriers of everyday consciousness and opening oneself up to a transcendent mode of experience; another is to temporarily surrender oneself up to an authoritarian teacher. The ninth-century Zen master Lin Chi is said to have beaten his disciples, even thrown one out of a second-story window, to shock them out of their worldly complacency. Reshad Feild's classic The Last Barrier: A Journey into the Essence of Sufi Teachings (1977) vividly describes how his teacher assaulted his worldly assumptions. One of his less-resilient fellow questers was driven insane. Of course all gurus are not so overbearing. Some hold out the paradisical prospect of limitless sex; still others terrify their followers with prophecies of a coming catastrophe that only they can save them from.

Religious movements, like businesses, require a constantly refreshed stream of customers in order to grow or merely keep pace with their natural rate of attrition. Recruitment and fund-raising are critical activities for cults, often carried out by the members themselves, who tirelessly distribute pamphlets on street corners, proselytize friends, family, and colleagues, and even use their bodies as lures (as female members of the Children of God were instructed to do in the 1960s and 1970s--a practice that their founder called "Flirty Fishing"). I have experienced some of this persuasion for myself and know how formidable it can be. For someone seeking to fill a void in his or her life, especially someone who is cut off from family and friends, it can be well-nigh irresistible.

When I was in my early twenties, one of my coworkers belonged to Arica, a syncretic movement founded by a Bolivian mystic named Oscar Ichazo, which brings together aspects of Gurdjieff's Fourth Way, Tai chi chuan, and ideas and practices associated with Esalen and the human potential movement, and wraps them up in a high-gloss package. As we got to know each other, he pressed me to accompany him to one of Arica's weekend retreats--strongly intimating that, if nothing else, I could meet attractive and accessible women there. When I finally broke down and did, I was immediately struck by three things: 1) that nearly every minute of the weekend was rigidly scripted--the session leaders had neither time nor toleration for questions or intellectual give-and-take; 2) that, rather than expounding or elaborating ideas, the teachers orchestrated experiences, through physical exercises and guided meditations, which were specifically designed to whet one's appetite for more; 3) that none of the women attending paid the slightest bit of attention to me.

Nothing bad happened; nobody tried to brainwash me or steal my money. But somewhere around the halfway point, I distinctly remember feeling a twinge of resentment when I realized that nobody wanted to engage me or persuade me or establish a relationship with me--instead they were trying to break down my resistance, to lull me into a state of susceptibility, to rope me in. I wasn't exactly in danger, but I felt obscurely threatened. I understood that to receive enlightenment on someone else's terms required an act of surrender that I wasn't prepared to make.

Clearly the path to enlightenment can be a perilous one for masters and disciples alike, with figurative and all-too-literal robbers, rapists, and murderers lurking behind every tree. The too-compliant initiate can be reduced to zombiehood; an unscrupulous or undisciplined master can easily yield to the temptation to take carnal or material advantage of the power they wield--or succumb to the delusion that they themselves are the Messiah or even God. It is a story that will be told again and again in the pages that follow.

Aetherius Society (see Area 51 in Conspiracies)

Amma the Hugging Saint, or Mata Amritanandamayai

(see Indian Gurus)

Assassins

Storied Muslim cult which held sway in remote areas of Persia and Iraq and made inroads into Syria for a period in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Like the Druze, the Assassins were an outgrowth of Ismailism, a schismatic movement within the already-schismatic Shiism. Like the Shiites, the Ismailis believe that the succession passes from Muhammad through Ali and Fatimid, but they disagree about the identity of the Seventh Imam. While Twelvers, the majority of Shiites, believe he was Musa al-Kadhim (746-799), Ismailis say he was Isma'il ibn Jafar (721-755). The Ismailis themselves would schism in 1094 over another dispute about the succession of the caliphate. After the death of the Eighteenth Imam, Mustansir, in 1094, some supported his younger son Musta'li (d. 1101); some supported his elder brother Nizar (ca. 1044-1095).

Hassan-i Sabbaah (1034-1124) would become the leader of the Nizarites. A widely traveled, well-connected Persian--the great poet and astronomer Omar Khayyam (1048-1122) was one of his schoolmates--Sabbah was forced into exile after he was accused of embezzling from the Shah. As cerebral as he was ruthless, he attended Al-Azhar University in Cairo, where he studied Ismailite philosophy. The Ismailites' esoteric teachings are highly syncretic, combining aspects of Neoplatonism, Manichaean dualism, and Gnosticism. At their heart is the notion that the conflict between good and evil begins within the nature of God, and that the world is a product of divine emanations that contain both light and darkness. Only a select group of students was admitted to Ismailism's inner circle--according to some accounts, initiation was accomplished through nine degrees of knowledge (a system that anticipated secret societies like the Masons).

What Makes a Cult Cultish?

The dictionary defines "cult" as a system of worship, but the word is usually used to denote a religious movement that is out of the mainstream. Christianity, for example, began as a cultic offshoot of Judaism, enjoying a similar status to the Essenes, the desert-dwelling ascetics who preserved the Dead Sea Scrolls, or the Samaritans, who not only belonged to a different ethnicity than the ancient Hebrews, but also didn't worship in the Temple in Jerusalem or acknowledge any but the first five books of the Bible. If a cult gains enough adherents, cultural currency, money, and other appurtenances of respectability, it generally becomes either a recognized denomination of the orthodoxy that spawned it or a full-fledged religion in its own right.

When members of one of those orthodoxies use the word "cult," more often than not they are using it pejoratively, to undercut a disreputably heterodox challenge to their own authority. Many evangelical Christians, for example, dismiss even such large, established movements as the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Church of Christ Scientist, and the Latter-Day Saints as cults, refusing to grant them the status of legitimate Christian denominations. On May 11, 2007, televangelist Bill Keller sent the following message about then-presidential hopeful Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts and a practicing Mormon, to the millions of subscribers to his daily Internet devotional, "LivePrayer":

Romney winning the White House will lead millions of people into the Mormon cult. Those who follow the false teachings of this cult, believe in the false Jesus of the Mormon cult and reject faith in the one true Jesus of the Bible, will die and spend eternity in hell.

Although my tone may be snarky at times, I strive to be agnostic when it comes to the tenets and doctrines of the movements I describe in these pages. Though I have occasionally given in to the temptation to write about a group merely because its ideas are entertainingly strange (a la Koreshanity), I am much more interested in the power relations between the leadership of a group and its members than I am in its doctrines. For the most part, when I characterize a group as a cult I am using the word as a social scientist or a psychologist would, to denote a coercive or totalizing relationship between a dominating leader and his or her unhealthily dependent followers. What makes a cult cultish is not so much what it espouses, but how much authority its leaders grant themselves--and how slavishly devoted to them its followers are.

On February 25, 2009, the Supreme Court issued its judgment in Pleasant Grove City, Utah v. Summum. Summum is a tiny sect founded in 1975 by Claude Nowell (1944-2008)--aka Corky King, Corky Ra, and Summum Bonum Amon Ra--whose members, among other things, mummify their pets and themselves after they die. A statue of the Ten Commandments stands in one of Pleasant Grove's public parks. Summum members wanted to erect a monument of their own commemorating their Seven Aphorisms* (according to Nowell's teachings, the aphorisms were inscribed on the tablets Moses smashed after his first descent from Mount Sinai; he received the Ten Commandments during his second ascent). Not surprisingly, Pleasant Grove did not wish to accommodate them, and the Supreme Court agreed that the city does not need to. Obviously Summum is more than a little weird by conventional standards--though Nowell claimed to have channeled his revelations from otherworldly beings, the theology he developed appears to be a hodgepodge of Masonic mysteries, Christian Gnosticism, and kitsch Egyptology--but it is not abusive or controlling and hence it does not fall under my rubric of "cult." Neither do the many iterations of Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Wicca, neo-paganism, Swedenborgianism, and many other occult, esoteric, and New Age movements that the Evangelicalist Web site Cultwatch devotes so much of its attention to.

Robert Lifton, the distinguished psychologist and author of such well-known books as The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (1986) and Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of "Brainwashing" in China (1961), defined cults in a 1981 article in the Harvard Mental Health Letter as an "aspect of a worldwide epidemic of ideological totalism, or fundamentalism." Cults, he continued, can be identified by three characteristics: 1) a charismatic leader "who increasingly becomes an object of worship"; 2) a process of "coercive persuasion or thought reform" (brainwashing, in other words); and 3) economic, sexual, or psychological exploitation of the rank-and-file members by the cult's leadership. The chief tool of "coercive persuasion," Lifton writes, is "milieu control; the control of all communication within a given environment."

Scientology has been accused of exploiting its acolytes and threatening its apostates, as has the Unification Church (its mass celebrations of arranged weddings, presided over by its founder and leader, Sun Myung Moon, epitomize the infringements of privacy and personal autonomy that so often go hand in glove with cult membership). Stephen Hassan, an ex-Moonie and an "exit counselor" for former cult members, defines a cult as a:

Pyramid-structured, authoritarian group or relationship where deception, recruitment, and mind control are used to keep people dependent and obedient. A cult can be a very small group or it can contain a whole country. The emphasis of mind control is what I call the BITE model: the control of behavior, information, thoughts, and emotions.

The Latter-Day Saints may be big enough and mainstream enough today to qualify as a religion, but many of the unaffiliated polygamous sects that style themselves as fundamentalist Mormons fit Lifton's and Hassan's definitions of a cult to a T, in that their leaders assume Godlike powers at the expense of their followers' autonomy and individuality. Alma Dayer LeBaron (1886-1951) led his polygamous followers to Mexico in the 1920s when he started his breakaway sect, the Church of the Lamb of God; over the next eighty years his sons Ervil, Joel, and Verlan fought bloodily over the succession, as did the fratricidal generation that followed theirs. While they carried on the family business of writing visionary screeds and murdering anyone who challenged their authority, they put their child brides and neglected children to work stealing cars, dealing drugs, and fencing stolen goods. Warren Jeffs, who succeeded his father, Rulon Jeffs (1909-2002), as President and Prophet, Seer and Revelator of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, has been convicted of "accomplice rape" for forcing minors into marriage.

Of course renegade Mormons don't have a monopoly on this sort of egregious behavior. A Hasidic rebbe who demands that his disciples submit every aspect of their personal and financial lives for his approval can justly be accused of cultism. The Armenian-Greek mystic G.I. Gurdjieff (1866?-1945) wrote books, composed music, and choreographed dances; his Fourth Way, an eclectic spiritual discipline which seeks to awaken the body, mind, and emotions, continues today under the auspices of the international Gurdjieff Society. But in his lifetime, he led a cult of personality; he was notoriously cruel and demanding to his students, who unreservedly gave themselves up to his power. His charisma was said to be so intense that he could cause a woman to have an orgasm just by looking at her across a room. 1 Mind Ministries, a tiny group led by a woman who calls herself Queen Antoinette, made headlines during the summer of 2008 when it was discovered that the one-year-old child of a member had been starved to death because he refused to say "amen."

A cult needn't be religious, either. The dancer Olgivanna Hinzenberg, one of Gurdjieff's disciples, married the architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). Wright's Taliesin school of architecture, where young architectural students performed virtual slave labor for the chance to learn from the master, had intensely cultish aspects to it. As Hassan notes, a whole country can devolve into cultishness--one need only think of Hitler's infamous Nuremberg rallies, Maoism at the height of China's Cultural Revolution, or the cult of personality surrounding Kim Jong Il, North Korea's "Dear Leader." A global, multilevel marketing concern like Amway, whose entrepreneurial leaders relentlessly pressure its salesmen to comport with their wider philosophy, to conform to their standards of success, to purchase only their approved products, and to associate only with their fellow Amway representatives, is no less cultic in some essential respects than the True Russian Orthodox Church, led by a schizophrenic named Pyotr Kuznetsov, whose thirty-some-odd members holed up in a cave in the Penza region of Central Russia in late 2007 to await the end of the world.

Then there are the cults of personality that grew up around supposed flying saucer contactees. George Adamski (1891-1965) was a self-proclaimed teacher of Tibetan wisdom and a would-be science fiction writer until he announced that he had been contacted by a Venusian named Orthon who told him about the dangers of nuclear war. Later he was taken for a ride in a flying saucer--adventures he recounted in his books Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953) and Inside the Spaceships (1955). Billy Meier is an ex-farmer from Switzerland who says he has been in communion with astronauts from the Pleiades star cluster since he was five years old. Thanks to their instruction, Meier says, he has achieved "the highest degree of spiritual evolution of any human being on earth." Though neither man had mass followings or required their disciples to worship them, the "nonprofit" foundations that they founded handsomely supported their various endeavors.

Mystical practice--whether in Buddhism, Hinduism, Sufism, Kabbalism, or the ecstatic Christianity of Meister Eckehart, Saint John of the Cross, and Teresa of Avila--is the pursuit of egolessness. Yoga and meditation are one means of dissolving the barriers of everyday consciousness and opening oneself up to a transcendent mode of experience; another is to temporarily surrender oneself up to an authoritarian teacher. The ninth-century Zen master Lin Chi is said to have beaten his disciples, even thrown one out of a second-story window, to shock them out of their worldly complacency. Reshad Feild's classic The Last Barrier: A Journey into the Essence of Sufi Teachings (1977) vividly describes how his teacher assaulted his worldly assumptions. One of his less-resilient fellow questers was driven insane. Of course all gurus are not so overbearing. Some hold out the paradisical prospect of limitless sex; still others terrify their followers with prophecies of a coming catastrophe that only they can save them from.

Religious movements, like businesses, require a constantly refreshed stream of customers in order to grow or merely keep pace with their natural rate of attrition. Recruitment and fund-raising are critical activities for cults, often carried out by the members themselves, who tirelessly distribute pamphlets on street corners, proselytize friends, family, and colleagues, and even use their bodies as lures (as female members of the Children of God were instructed to do in the 1960s and 1970s--a practice that their founder called "Flirty Fishing"). I have experienced some of this persuasion for myself and know how formidable it can be. For someone seeking to fill a void in his or her life, especially someone who is cut off from family and friends, it can be well-nigh irresistible.

When I was in my early twenties, one of my coworkers belonged to Arica, a syncretic movement founded by a Bolivian mystic named Oscar Ichazo, which brings together aspects of Gurdjieff's Fourth Way, Tai chi chuan, and ideas and practices associated with Esalen and the human potential movement, and wraps them up in a high-gloss package. As we got to know each other, he pressed me to accompany him to one of Arica's weekend retreats--strongly intimating that, if nothing else, I could meet attractive and accessible women there. When I finally broke down and did, I was immediately struck by three things: 1) that nearly every minute of the weekend was rigidly scripted--the session leaders had neither time nor toleration for questions or intellectual give-and-take; 2) that, rather than expounding or elaborating ideas, the teachers orchestrated experiences, through physical exercises and guided meditations, which were specifically designed to whet one's appetite for more; 3) that none of the women attending paid the slightest bit of attention to me.

Nothing bad happened; nobody tried to brainwash me or steal my money. But somewhere around the halfway point, I distinctly remember feeling a twinge of resentment when I realized that nobody wanted to engage me or persuade me or establish a relationship with me--instead they were trying to break down my resistance, to lull me into a state of susceptibility, to rope me in. I wasn't exactly in danger, but I felt obscurely threatened. I understood that to receive enlightenment on someone else's terms required an act of surrender that I wasn't prepared to make.

Clearly the path to enlightenment can be a perilous one for masters and disciples alike, with figurative and all-too-literal robbers, rapists, and murderers lurking behind every tree. The too-compliant initiate can be reduced to zombiehood; an unscrupulous or undisciplined master can easily yield to the temptation to take carnal or material advantage of the power they wield--or succumb to the delusion that they themselves are the Messiah or even God. It is a story that will be told again and again in the pages that follow.

Aetherius Society (see Area 51 in Conspiracies)

Amma the Hugging Saint, or Mata Amritanandamayai

(see Indian Gurus)

Assassins

Storied Muslim cult which held sway in remote areas of Persia and Iraq and made inroads into Syria for a period in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Like the Druze, the Assassins were an outgrowth of Ismailism, a schismatic movement within the already-schismatic Shiism. Like the Shiites, the Ismailis believe that the succession passes from Muhammad through Ali and Fatimid, but they disagree about the identity of the Seventh Imam. While Twelvers, the majority of Shiites, believe he was Musa al-Kadhim (746-799), Ismailis say he was Isma'il ibn Jafar (721-755). The Ismailis themselves would schism in 1094 over another dispute about the succession of the caliphate. After the death of the Eighteenth Imam, Mustansir, in 1094, some supported his younger son Musta'li (d. 1101); some supported his elder brother Nizar (ca. 1044-1095).

Hassan-i Sabbaah (1034-1124) would become the leader of the Nizarites. A widely traveled, well-connected Persian--the great poet and astronomer Omar Khayyam (1048-1122) was one of his schoolmates--Sabbah was forced into exile after he was accused of embezzling from the Shah. As cerebral as he was ruthless, he attended Al-Azhar University in Cairo, where he studied Ismailite philosophy. The Ismailites' esoteric teachings are highly syncretic, combining aspects of Neoplatonism, Manichaean dualism, and Gnosticism. At their heart is the notion that the conflict between good and evil begins within the nature of God, and that the world is a product of divine emanations that contain both light and darkness. Only a select group of students was admitted to Ismailism's inner circle--according to some accounts, initiation was accomplished through nine degrees of knowledge (a system that anticipated secret societies like the Masons).

Recenzii

“The kind of reference manual that the Internet cannot supplant . . . Goldwag keeps the facts straight and gives the rumors -- no matter how lurid and entertaining -- about as much respect as they deserve.”—The Washington Post

“Marvelous.”—Scientific American

“Arthur Goldwag is a shrewd, fair minded, learned and entertaining tour guide through a world that’s simultaneously funny and frightening. Not a page goes by without some “I-didn’t-know-that!” nugget. Given what’s going on this ever-more-paranoid society, a book like this becomes not only titillating but crucially important.”—Steven Waldman, Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Beliefnet.com

“The answer to your burning questions about subjects from Area 51 to the Yakuza.”—Details

“Delightful.” –The Weekly Standard

“Goldwag is a colorful writer who makes good use of his material as he aims to explain, rather than debunk or expose, a fascinating diversity of beliefs.”—Boston Globe

“The author’s delivery is engaging and entertaining. The amount of research done in this book is astounding. . . . An incredibly insightful, thoroughly enjoyable look at society’s shadow.”—Armchair Interviews

“Goldwag navigates his way through the wilder reaches of human belief with great urbanity.”

—Mark Booth, author of The Secret History of the World: As Laid Down by the Secret Societies

“As entertainingly written as it is enlightening.”

—Phillip Lopate

“Marvelous.”—Scientific American

“Arthur Goldwag is a shrewd, fair minded, learned and entertaining tour guide through a world that’s simultaneously funny and frightening. Not a page goes by without some “I-didn’t-know-that!” nugget. Given what’s going on this ever-more-paranoid society, a book like this becomes not only titillating but crucially important.”—Steven Waldman, Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Beliefnet.com

“The answer to your burning questions about subjects from Area 51 to the Yakuza.”—Details

“Delightful.” –The Weekly Standard

“Goldwag is a colorful writer who makes good use of his material as he aims to explain, rather than debunk or expose, a fascinating diversity of beliefs.”—Boston Globe

“The author’s delivery is engaging and entertaining. The amount of research done in this book is astounding. . . . An incredibly insightful, thoroughly enjoyable look at society’s shadow.”—Armchair Interviews

“Goldwag navigates his way through the wilder reaches of human belief with great urbanity.”

—Mark Booth, author of The Secret History of the World: As Laid Down by the Secret Societies

“As entertainingly written as it is enlightening.”

—Phillip Lopate

Descriere

This intriguing guide connects the dots and sets the record straight on a host of greedy gurus, murderous messiahs, and suspicious coincidences. Divided into three sections, its hundreds of entries separate facts from myths.