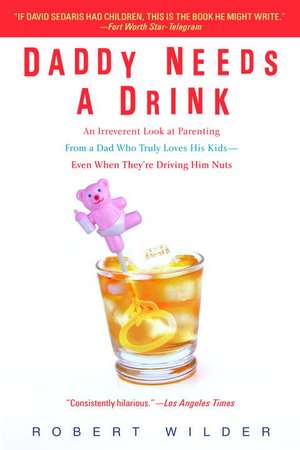

Daddy Needs a Drink: An Irreverent Look at Parenting from a Dad Who Truly Loves His Kids--Even When They're Driving Him Nuts

Autor Robert Wilderen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2007

With an artist wife and two kids—a daughter, Poppy, and a son, London—Robert Wilder considers himself as open-minded as the next man. Yet even he finds himself parentally challenged when his toddler son, London, careens around the house in the buff or asks the kind of outrageous, embarrassing questions only a kid can ask. A high school teacher who sometimes refers to himself jokingly as Mister Mom (when his wife, Lala, is busy in her studio), Wilder shares warmly funny stories on everything from sleep deprivation to why school-sponsored charities can turn otherwise sane adults into blithering and begging idiots.

Whether trying to conjure up the perfect baby name (“Poppy” came to his wife’s mother in a dream) or hiring a Baby Whisperer to get some much-needed sleep, Wilder offers priceless life lessons on discipline, potty training, even phallic fiddling (courtesy of young London). He describes the perils of learning to live monodextrously (doing everything with one hand while carrying your child around with the other) and the joys of watching his daughter morph into a graceful, wise, unique little person right before his eyes.

By turns tender, irreverent, and hysterically funny, Daddy Needs a Drink is a hilarious and poignant tribute to his family by a man who truly loves being a father.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 94.04 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 141

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.99€ • 18.83$ • 14.95£

17.99€ • 18.83$ • 14.95£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385339261

ISBN-10: 0385339267

Pagini: 273

Dimensiuni: 142 x 209 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0385339267

Pagini: 273

Dimensiuni: 142 x 209 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: DELTA

Notă biografică

Robert Wilder is a writer and teacher who lives with his wife and two children, Poppy and London, in New Mexico. He has appeared on NPR's Morning Edition, and has a monthly column for the Santa Fe Reporter also called "Daddy Needs a Drink."

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Hoarding Names

In terms of upbringing, my wife, Lala, and I led mirror lives as children. I grew up with three brothers in New York and Connecticut with my dad, while Lala was raised in Colorado and Wyoming with a trio of sisters and her mother. Even though we've known each other for fifteen years, there are still many things I do not understand about Lala or the female species in general. I believe some simple concepts can be taught to men, such as the length of the menstruation cycle or the appreciation of a closetful of narrow footwear; we can even learn to spot and compliment a recent haircut if given the proper training. However, some of the abstract and less forensic female notions still remain puzzling to me.

My wife has been nesting her whole life, even before she thought about having children. A folk artist by trade and by obsession, she's the kind of person who believes if a week goes by without rearranging furniture, you're halfway to the grave. When she was pregnant with our first child, the change-it-up home show occurred even more frequently than usual. I'd come home from waiting tables at 2 a.m. to find Lala covered in paint and standing by a half-finished wall, a color swatch in each hand.

"Do you like the Daredevil or the Blaze of Glory?" she'd ask, shoving the cards in my face.

"They both look red to me," I'd say.

"Come on, really," she'd plead, desperate for a way out of the latex corner she'd painted herself into.

"Truly, I can't tell the difference." I'm not colorblind, yet shades of the same hue just don't move me in a decision-making direction the way a dinner menu does. My indifference toward interior decorating goes deeper even: I simply don't care. It's hard for Lala to believe, but for this caveman, if I don't trip on anything in my house and I have a place to sit that's not wet, I feel pretty good. I'd rather have things put away and no dishes in the sink than Tiffany lampshades and a red velvet couch. Except for their lack of underwear that supports, I often envy those silly little Tibetan monks with their polished floors and black pillows. If they had cable and beer on tap, I'd be hard-pressed not to pony up and join.

Lala is a determined creature, and now that a baby was on the way, the choices she offered me were no longer just about tinge and tincture. She stood on the second rung of our ladder, her brush moving across the ceiling in long strokes while her large belly kept her from getting to those hard-to-reach places. She knew better than to ask me for help, however, just as I knew better than to ask her to shout the football score to me while I was on the toilet.

"What do you think of the name Hemingway?" she called down.

"Are you kidding?" I asked.

"No, why?" She paused and faced me, resting her brush on the top rung.

"I'm an English teacher and a writer."

"So?"

"What would you think of a math teacher with a kid named Hypotenuse or Pythagoras?"

"You overthink things. I like the sound of it." She craned her neck and eyed her handiwork above our

heads. "Hemingway Wilder." She sighed, hoping to gain my sympathy.

"Where'd you get that name anyway?" I asked, slightly changing the subject.

She shrugged. "From my list."

I then became enlightened on one of the strange behaviors of the Carroll sisters and, as I found out later, other women I have met. Starting at the age of pretend weddings with younger siblings or household pets, some women keep lists of names for their future children. Even though I grew up in a household where eating in your boxers was acceptable dinner dress, I knew that women had a distinct vision of their perfect wedding, complete with seating diagrams, fabric swatches, and guesses as to which bridesmaid would most likely go down on smelly Uncle Louie.

I had no idea that ever since she was running barefoot in her grandfather's silo Lala had been hoarding names. She had dozens for girls, fewer for boys (everyone knows boys' names are harder, she informed me), and a handful that could fit either team or a very special sheepdog. When I was a kid, what people called me held virtually no importance, since all the Wilder boys had almost interchangeable names. The four of us have each other's first names as middle names and vice versa. My parents had been unable to produce offspring for ten years and had almost given up until my older brother Rich was born. Since they thought he'd be their last, my mom and dad named him after my mother's grandfather and father: Richard Edward. I popped out two years later, and I got my father's part of the bargain: Robert (his father) Thomas (his grandfather). Out of exhaustion or distinct lack of imagination, my two younger brothers got stuck with a rearranging of what already came before: Thomas Edward and Edward Robert Wilder. Sometimes I feel that such an inbred naming process makes us southern somehow by proxy.

Lala would ask me for my opinion on what we should call our child, and most of the time I felt neutral about the choices, not unlike when she showed me swatches labeled Weeping Sky and Dodger Blue. Even I grew bored with my own dull responses, so I took on a more proactive male role by trying to predict the nicknames or associations that might plague our offspring during their undoubtedly misspent youths-to-be.

"I think Bea is cute," Lala said one day while she rolled Coca-Cola Red onto our antique refrigerator.

"No way," I said. "I'd look at our daughter and think of Bea Arthur. That woman gave me nightmares."

"How about Macauley?"

"Besides being too Irish, it would remind me of Macauley Culkin."

"So?"

"I don't want my kid associated with that creepy child actor. He's a bit too close to Michael Jackson. I read that M.J. has a photo of Macaulay in his bathroom. Gives a whole new meaning to Home Alone."

"Jesus, nobody but you would think like that." She shook her hand disapprovingly at her academic egghead of a husband.

"You never know."

Our daughter's name wasn't even on Lala's list. Her mother, Beverly, had a dream that our first child would be a girl named Poppy. We thought Beverly had been working at Grier's furniture store, a former mortuary, for far too long, and treated her whole idea as silly. When we did find a time and way to get pregnant, however, we jokingly referred to the embryo as Poppy, and it stuck. Every other name--Addison, Grayson, Kirkum--all sounded too formal next to a fun floral forename. I even held back from sharing with Lala all the possible scenarios on the middle-school playground--Pop Goes the Weasel, Popcorn, Soda Pop, and far less pleasant things that pop for a girl during adolescence.

After Poppy was born, the name game did not go away as I'd hoped. A year later, my brother Rich called to tell me that his wife just had a baby girl, and they had named her Madeleine with the middle name Joan after my late mother.

"Well, that's rude," Lala said, slamming a wooden paint stirrer against the kitchen counter she had sanded only moments before.

"Why? Did you want to use Joan on our next kid?"

"Are you kidding? I hate that name." She took her fingernail and picked at a rough spot of Formica. "Now Poppy will have two cousins named Maddie. That's just great." Lala's older sister Kate had registered the Madeleine trademark in Seattle years before. "Just think how confused Poppy will be and how exhausting for us to use last names when talking about first cousins. I wish they'd called to check with me."

This botched title search happened again not so long after the Maddie business when Lala's younger sister Emily took Poppy's middle name, Olivia, as the first for her new daughter.

"I cannot believe this," Lala said when her sister broke the news over the phone. Emily admitted that the name had been on Lala's list, but she tried to convince her it had been on Emily's as well. The case is still pending in appellative court. "From now on," Lala told me, "we are not sharing our list with anyone. When people at work ask you which ones you like or what other names we had for Poppy, you absolutely cannot say." She paused, and her eyes lit up like the square of Goldenrod taped to the wall over our bed. "Better yet, let's think of some phony names to throw those name snatchers off the scent!"

"Like what?"

"I don't know." She shrugged, then looked around the house for inspiration. Rectangles of colored paper lay scattered on tables like a shrunken game of fifty-two pickup. "I got it," she said, weeding through the cards and choosing a few. "Rose, Coral, Scarlet, Indigo."

"Indigo? Who the hell do you think I am, Lenny Kravitz? No one will buy that."

"I don't care. Those are the ones you'll tell all those name stealers."

"You are out of your skull." I waved my hand at her.

"Oh am I?" she asked, wagging one spackled finger. "Tell that to your daughter when she comes to you in tears because all her cousins have the same goddamn names. We might as well move to Russia."

"Russia?"

"You know what I mean. Vladimir this, Boris that. I wonder if they have a problem with name theft over there. I bet you they do."

Lala treated this name theft business like national security secrets stolen from Los Alamos Laboratory, only a Home Improvement episode from where we live. She wasn't the only one mucking about with this moniker malfeasance. A college friend's wife, Margaret, belongs to a mommies' group. When Margaret found out she was pregnant, she joined a birthing class that ended up forming into a social support club for women expecting their first child. The eight mamacitas completed the birthing class together, survived prenatal yoga, and cheered each other on during the series of births. Now two hundred pounds thinner, the group still met to discuss postpartum depression and sex after a cesarean, staying together even as some members became pregnant with kid number two. They shared everything from husband frustrations to lactation issues and, also unfortunately for Margaret, names.

The mommies' group had gathered at a new restaurant in town to celebrate Margaret and another mom, Laura, who were both due within a few weeks of each other. While the non-nursing, non-expecting moms made up for all the lost drinking time chugging glasses of Chardonnay, Margaret, high on hormones, chatted freely about possible names for her second coming. She was due before Laura, so she believed her list was safe. She hadn't visited my multicolored house nor sought the advice of Lala the Namekeeper and her stealth strategies of keeping secrets. Margaret told the assembled group her first, second, and third choices. Everyone discussed the merits of each and quickly launched into her own naming story. Laura, the other swollen one, smiled but remained silent.

Laura gave birth first and used Margaret's name for her bundle of joy. It's close to a year later now, and Margaret is still not over it. If you ask her the name of her child, she'll say, "Well, her name is Jade. We originally wanted to use Amber, but we couldn't." Then she'll drop her head, mourning those five stolen letters.

I wonder if as Jade grows up the unrealized first choice will follow her like a rap sheet. I can see her first-grade teacher calling roll: "Jade should-have-been-Amber, please raise your hand." Then the obvious follow-up, "By any chance, are you related to the artist formerly known as Prince?"

Lala and I are finished with that whole child-having business. Our second, a boy we named London, proved also to be a difficult birth and narrowly escaped other, more unpleasant monikers. Given our finances, overscheduled lives, and dumb luck in creating one child of each gender, I figured it was time to pull the mucous plug. Why go to zone defense when you survive just fine with man-to-man? A lot of teachers at my school are having babies lately, and the naming process is a frequent topic of conversation around the faculty lunch trough. Not so long ago, I came home and told Lala that I thought Bea would fit the global studies teacher's last name quite well.

"Did you tell her that?" she asked me coldly.

"Yes?" I knew from her gaze that I was in deep shit.

"I thought we agreed not to share our names. What happened to Indigo?"

"What does it matter?" I asked. "We're done with that messy birth stuff."

"I'm saving our names for Poppy," she said, turning her attention back to priming the trim on the

living room windows.

"Poppy is happy with her name," I said. "She won't want to change it."

"For later," she replied, still avoiding my now befuddled mug. "For Poppy's children."

"Poppy is only eight years old. Are you kidding me?"

"Nope." She pulled two swatches off the wall, held by pieces of blue painter's tape, the kind that is not very sticky. "Now," she said calmly, "which do you like for the windowsill: Jamaica Bay or Wild Blue Yonder?"

From the Hardcover edition.

In terms of upbringing, my wife, Lala, and I led mirror lives as children. I grew up with three brothers in New York and Connecticut with my dad, while Lala was raised in Colorado and Wyoming with a trio of sisters and her mother. Even though we've known each other for fifteen years, there are still many things I do not understand about Lala or the female species in general. I believe some simple concepts can be taught to men, such as the length of the menstruation cycle or the appreciation of a closetful of narrow footwear; we can even learn to spot and compliment a recent haircut if given the proper training. However, some of the abstract and less forensic female notions still remain puzzling to me.

My wife has been nesting her whole life, even before she thought about having children. A folk artist by trade and by obsession, she's the kind of person who believes if a week goes by without rearranging furniture, you're halfway to the grave. When she was pregnant with our first child, the change-it-up home show occurred even more frequently than usual. I'd come home from waiting tables at 2 a.m. to find Lala covered in paint and standing by a half-finished wall, a color swatch in each hand.

"Do you like the Daredevil or the Blaze of Glory?" she'd ask, shoving the cards in my face.

"They both look red to me," I'd say.

"Come on, really," she'd plead, desperate for a way out of the latex corner she'd painted herself into.

"Truly, I can't tell the difference." I'm not colorblind, yet shades of the same hue just don't move me in a decision-making direction the way a dinner menu does. My indifference toward interior decorating goes deeper even: I simply don't care. It's hard for Lala to believe, but for this caveman, if I don't trip on anything in my house and I have a place to sit that's not wet, I feel pretty good. I'd rather have things put away and no dishes in the sink than Tiffany lampshades and a red velvet couch. Except for their lack of underwear that supports, I often envy those silly little Tibetan monks with their polished floors and black pillows. If they had cable and beer on tap, I'd be hard-pressed not to pony up and join.

Lala is a determined creature, and now that a baby was on the way, the choices she offered me were no longer just about tinge and tincture. She stood on the second rung of our ladder, her brush moving across the ceiling in long strokes while her large belly kept her from getting to those hard-to-reach places. She knew better than to ask me for help, however, just as I knew better than to ask her to shout the football score to me while I was on the toilet.

"What do you think of the name Hemingway?" she called down.

"Are you kidding?" I asked.

"No, why?" She paused and faced me, resting her brush on the top rung.

"I'm an English teacher and a writer."

"So?"

"What would you think of a math teacher with a kid named Hypotenuse or Pythagoras?"

"You overthink things. I like the sound of it." She craned her neck and eyed her handiwork above our

heads. "Hemingway Wilder." She sighed, hoping to gain my sympathy.

"Where'd you get that name anyway?" I asked, slightly changing the subject.

She shrugged. "From my list."

I then became enlightened on one of the strange behaviors of the Carroll sisters and, as I found out later, other women I have met. Starting at the age of pretend weddings with younger siblings or household pets, some women keep lists of names for their future children. Even though I grew up in a household where eating in your boxers was acceptable dinner dress, I knew that women had a distinct vision of their perfect wedding, complete with seating diagrams, fabric swatches, and guesses as to which bridesmaid would most likely go down on smelly Uncle Louie.

I had no idea that ever since she was running barefoot in her grandfather's silo Lala had been hoarding names. She had dozens for girls, fewer for boys (everyone knows boys' names are harder, she informed me), and a handful that could fit either team or a very special sheepdog. When I was a kid, what people called me held virtually no importance, since all the Wilder boys had almost interchangeable names. The four of us have each other's first names as middle names and vice versa. My parents had been unable to produce offspring for ten years and had almost given up until my older brother Rich was born. Since they thought he'd be their last, my mom and dad named him after my mother's grandfather and father: Richard Edward. I popped out two years later, and I got my father's part of the bargain: Robert (his father) Thomas (his grandfather). Out of exhaustion or distinct lack of imagination, my two younger brothers got stuck with a rearranging of what already came before: Thomas Edward and Edward Robert Wilder. Sometimes I feel that such an inbred naming process makes us southern somehow by proxy.

Lala would ask me for my opinion on what we should call our child, and most of the time I felt neutral about the choices, not unlike when she showed me swatches labeled Weeping Sky and Dodger Blue. Even I grew bored with my own dull responses, so I took on a more proactive male role by trying to predict the nicknames or associations that might plague our offspring during their undoubtedly misspent youths-to-be.

"I think Bea is cute," Lala said one day while she rolled Coca-Cola Red onto our antique refrigerator.

"No way," I said. "I'd look at our daughter and think of Bea Arthur. That woman gave me nightmares."

"How about Macauley?"

"Besides being too Irish, it would remind me of Macauley Culkin."

"So?"

"I don't want my kid associated with that creepy child actor. He's a bit too close to Michael Jackson. I read that M.J. has a photo of Macaulay in his bathroom. Gives a whole new meaning to Home Alone."

"Jesus, nobody but you would think like that." She shook her hand disapprovingly at her academic egghead of a husband.

"You never know."

Our daughter's name wasn't even on Lala's list. Her mother, Beverly, had a dream that our first child would be a girl named Poppy. We thought Beverly had been working at Grier's furniture store, a former mortuary, for far too long, and treated her whole idea as silly. When we did find a time and way to get pregnant, however, we jokingly referred to the embryo as Poppy, and it stuck. Every other name--Addison, Grayson, Kirkum--all sounded too formal next to a fun floral forename. I even held back from sharing with Lala all the possible scenarios on the middle-school playground--Pop Goes the Weasel, Popcorn, Soda Pop, and far less pleasant things that pop for a girl during adolescence.

After Poppy was born, the name game did not go away as I'd hoped. A year later, my brother Rich called to tell me that his wife just had a baby girl, and they had named her Madeleine with the middle name Joan after my late mother.

"Well, that's rude," Lala said, slamming a wooden paint stirrer against the kitchen counter she had sanded only moments before.

"Why? Did you want to use Joan on our next kid?"

"Are you kidding? I hate that name." She took her fingernail and picked at a rough spot of Formica. "Now Poppy will have two cousins named Maddie. That's just great." Lala's older sister Kate had registered the Madeleine trademark in Seattle years before. "Just think how confused Poppy will be and how exhausting for us to use last names when talking about first cousins. I wish they'd called to check with me."

This botched title search happened again not so long after the Maddie business when Lala's younger sister Emily took Poppy's middle name, Olivia, as the first for her new daughter.

"I cannot believe this," Lala said when her sister broke the news over the phone. Emily admitted that the name had been on Lala's list, but she tried to convince her it had been on Emily's as well. The case is still pending in appellative court. "From now on," Lala told me, "we are not sharing our list with anyone. When people at work ask you which ones you like or what other names we had for Poppy, you absolutely cannot say." She paused, and her eyes lit up like the square of Goldenrod taped to the wall over our bed. "Better yet, let's think of some phony names to throw those name snatchers off the scent!"

"Like what?"

"I don't know." She shrugged, then looked around the house for inspiration. Rectangles of colored paper lay scattered on tables like a shrunken game of fifty-two pickup. "I got it," she said, weeding through the cards and choosing a few. "Rose, Coral, Scarlet, Indigo."

"Indigo? Who the hell do you think I am, Lenny Kravitz? No one will buy that."

"I don't care. Those are the ones you'll tell all those name stealers."

"You are out of your skull." I waved my hand at her.

"Oh am I?" she asked, wagging one spackled finger. "Tell that to your daughter when she comes to you in tears because all her cousins have the same goddamn names. We might as well move to Russia."

"Russia?"

"You know what I mean. Vladimir this, Boris that. I wonder if they have a problem with name theft over there. I bet you they do."

Lala treated this name theft business like national security secrets stolen from Los Alamos Laboratory, only a Home Improvement episode from where we live. She wasn't the only one mucking about with this moniker malfeasance. A college friend's wife, Margaret, belongs to a mommies' group. When Margaret found out she was pregnant, she joined a birthing class that ended up forming into a social support club for women expecting their first child. The eight mamacitas completed the birthing class together, survived prenatal yoga, and cheered each other on during the series of births. Now two hundred pounds thinner, the group still met to discuss postpartum depression and sex after a cesarean, staying together even as some members became pregnant with kid number two. They shared everything from husband frustrations to lactation issues and, also unfortunately for Margaret, names.

The mommies' group had gathered at a new restaurant in town to celebrate Margaret and another mom, Laura, who were both due within a few weeks of each other. While the non-nursing, non-expecting moms made up for all the lost drinking time chugging glasses of Chardonnay, Margaret, high on hormones, chatted freely about possible names for her second coming. She was due before Laura, so she believed her list was safe. She hadn't visited my multicolored house nor sought the advice of Lala the Namekeeper and her stealth strategies of keeping secrets. Margaret told the assembled group her first, second, and third choices. Everyone discussed the merits of each and quickly launched into her own naming story. Laura, the other swollen one, smiled but remained silent.

Laura gave birth first and used Margaret's name for her bundle of joy. It's close to a year later now, and Margaret is still not over it. If you ask her the name of her child, she'll say, "Well, her name is Jade. We originally wanted to use Amber, but we couldn't." Then she'll drop her head, mourning those five stolen letters.

I wonder if as Jade grows up the unrealized first choice will follow her like a rap sheet. I can see her first-grade teacher calling roll: "Jade should-have-been-Amber, please raise your hand." Then the obvious follow-up, "By any chance, are you related to the artist formerly known as Prince?"

Lala and I are finished with that whole child-having business. Our second, a boy we named London, proved also to be a difficult birth and narrowly escaped other, more unpleasant monikers. Given our finances, overscheduled lives, and dumb luck in creating one child of each gender, I figured it was time to pull the mucous plug. Why go to zone defense when you survive just fine with man-to-man? A lot of teachers at my school are having babies lately, and the naming process is a frequent topic of conversation around the faculty lunch trough. Not so long ago, I came home and told Lala that I thought Bea would fit the global studies teacher's last name quite well.

"Did you tell her that?" she asked me coldly.

"Yes?" I knew from her gaze that I was in deep shit.

"I thought we agreed not to share our names. What happened to Indigo?"

"What does it matter?" I asked. "We're done with that messy birth stuff."

"I'm saving our names for Poppy," she said, turning her attention back to priming the trim on the

living room windows.

"Poppy is happy with her name," I said. "She won't want to change it."

"For later," she replied, still avoiding my now befuddled mug. "For Poppy's children."

"Poppy is only eight years old. Are you kidding me?"

"Nope." She pulled two swatches off the wall, held by pieces of blue painter's tape, the kind that is not very sticky. "Now," she said calmly, "which do you like for the windowsill: Jamaica Bay or Wild Blue Yonder?"

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Wilder's collection is spiced with sharp-eyed but never cruel observations of kids' befuddling behavior and hilarious scatology…. His love for his family comes through without ever seeming cloying…. Capture[s] the absurdity and joy to be found in the most important job a man can do."—Los Angeles Times

“Robert Wilder’s hilarious and boldly candid essays about the realities of parenting go down like gin and tonic on a hot summer afternoon.”—People

"More profane, more ironic and at times more touching than a whole stack of well-meaning child-rearing manuals....Even if your husband or father or brother isn't much of a reader, Daddy Needs a Drink would be sure to make him laugh."—Cleveland Plain Dealer

From the Hardcover edition.

“Robert Wilder’s hilarious and boldly candid essays about the realities of parenting go down like gin and tonic on a hot summer afternoon.”—People

"More profane, more ironic and at times more touching than a whole stack of well-meaning child-rearing manuals....Even if your husband or father or brother isn't much of a reader, Daddy Needs a Drink would be sure to make him laugh."—Cleveland Plain Dealer

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Waxing both profound and profane on issues close to a father's heart, Wilder brilliantly captures the joys and absurdities of being a parent today.