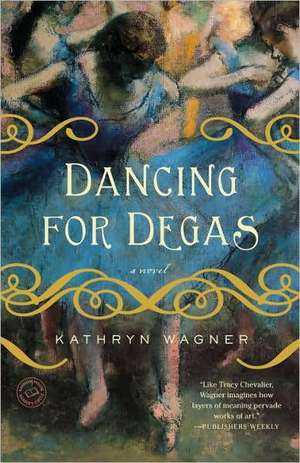

Dancing for Degas

Autor Kathryn Wagneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

With this fresh and vibrantly imagined portrait of the Impressionist artist Edgar Degas, readers are transported through the eyes of a young Parisian ballerina to an era of light and movement. An ambitious and enterprising farm girl, Alexandrie joins the prestigious Paris Opera ballet with hopes of securing not only her place in society but her family’s financial future. Her plan is soon derailed, however, when she falls in love with the enigmatic artist whose paintings of the offstage lives of the ballerinas scandalized society and revolutionized the art world. As Alexandrie is drawn deeper into Degas’s art and Paris’s secrets, will she risk everything for her dreams of love and of becoming the ballet’s star dancer?

Preț: 136.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 205

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.14€ • 28.38$ • 21.96£

26.14€ • 28.38$ • 21.96£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 22 aprilie-06 mai

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 78.94 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385343862

ISBN-10: 0385343868

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 130 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0385343868

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 130 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Notă biografică

Kathryn Wagner is a senior fundraiser for a child advocacy nonprofit in Washington, D.C. She holds a B.A. in journalism with a minor in art and has worked as a staff writer and columnist for several newspapers in North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Virginia. Imagining what has inspired great artists has been a longtime passion of hers. She is currently at work on her next novel.

Extras

No. 1 Scène: The Fiery Side of France

1859

I wasn’t always filled with such anxiety. The inescapable need for perfection was cultivated during many years of training—just as my body was strengthened to complete a flawless pirouette, my mind underwent vigorous instruction until I believed that I was better than all others and entitled to nothing short of the riches of an empress. Yet it was no secret that I could be dethroned without a second thought. My success was nothing but an illusion, which I find especially ironic because I was not born into such complications. I sought them out.

At the age of twelve, when all the girls around me seemed to be blossoming, I was painfully average. Others received praise for their looks and talents, while I faded into the background. Once in a while someone would compliment my startling green eyes, but this only happened when there was no one else in the vicinity and nothing else to focus on. And, believe me, one had to put quite a bit of focus into the task of taking notice. They had to overlook my gangly, awkward body, my clothes that always seemed to attract dirt, my drab, brown hair that always managed to become unruly. It was a wonder to me how other girls seemed to not have to give their hair a second thought. I couldn’t stop staring at the locks that cascaded over their shoulders in one fluid motion like corn silk. My wavy hair seemed to feed off of hairbrushes, growing larger and larger with each stroke. Like a horse running wild, I could not control it so I chose instead to suppress it under limp bonnets.

My hair was only the start of my ordinary existence. I grew taller than most girls my age, but not so tall that I drew attention, only tall enough to look clumsy by comparison. I loathed running into the Neville family at the market. Madame Neville had given birth to a staggering number of children, ten the last time I counted and all girls, all names beginning with N—Nathalie, Nicole, Naomi, and so on. I was sure they would run out of N names if she didn’t stop having children. The Neville girls were tiny, so tiny that they drew crowds as they followed behind their mother like a row of ducklings with shiny white heads of hair. I hated when my mother would stop to pay her respects to Madame Neville and I would find myself stuck in the middle of the group, my head rising above the girls like a large, scruffy dog amongst a litter of kittens. The only company I kept was my mother’s, with just one brother who mimicked my father’s apathy toward me as if neither could be bothered with the trivial thoughts of a girl, and thus I really had no idea how to talk to children my own age. When passersby would stop and coo that the Neville girls looked just like a group of porcelain dolls, my face would grow red and I would stare down at my shoes. I remember peering over at Madame Neville, who basked in the glow of the compliments, a baby thrust onto her hip, and noticing how her body resembled a pyramid, becoming wider and wider until her bottom sagged down so low that it seemed it would surely touch the ground. I thought with some satisfaction that these tiny girls would grow to be only as tall as their mother. They wouldn’t be able to grow higher, so they would grow wider until each of the little dolls resembled walking pyramids as well.

While I was much too shy and proper to have said such a terrible thing aloud, I did constantly think terrible thoughts of others. Perhaps it was from being overlooked so often; I had nothing else to do but observe those around me and find faults to rival the compliments they were given. If a girl received praise for her exquisite needlework while I tried to hide the knots that formed in mine, I would shrug my shoulders and console myself with the thought that of course her needlework was perfect, she had such large bug eyes that the tiny stitches must surely be magnified to her!

Such thoughts entertained me as I began morning chores each day at our tiny farmhouse which meandered off the path from the small winding streets of our little town of Espelette. Espelette was as painfully ordinary as myself, with only its spicy pepper crop bringing it any recognition. Locals called it the fiery side of France, although there was nothing sizzling about it in my opinion. My father grew hot peppers, just like every other farmer in the town.

“Alexandrie, don’t let the eggs sit over the fire, keep stirring them so they scramble properly,” my mother’s shrill voice interrupted my thoughts as she cut thick slices of bread, spreading butter over them. “Your father and brother have a long day of work ahead and they need a hearty breakfast.”

As I whipped the fork through the eggs, I paused to watch them puff up, letting a huge bubble form and then poking my fork in the center so it burst.

“Alexandrie, I told you if you let the eggs sit they become rubbery,” my mother said, exasperated.

“You should know these things by now,” she added while guiding my hands. “I can only pray that one day you’ll make a good wife.” I saw how effortless it was for her and wished she would just finish it since her arms were so much larger and stronger than mine.

“What difference does it really make?” I complained. “We spend all of this time making breakfast and then Denis and Papa rush in and eat it in minutes. Why can’t we eat before them so we can have eggs too? Most of the time there isn’t anything left for us but a slice of bread.”

“If we eat first, then there might not be enough for them,” she told me in a singsong voice that made me wonder how she could sound so happy about something that was so unfair.

I felt as if we lived in the kitchen. As soon as one meal ended we had to begin preparing for the next. We never stopped throughout the day. In between our kitchen duties we would hang freshly harvested peppers on our front and back porches to dry. We worked quickly, throwing the dried ones in a bag to be ground into a fine powder. I spent each afternoon hunched over the funny red vegetables, smashing them into dust to be sold at the market, all the while careful not to touch my face. I once made the mistake of rubbing my eye in the midst of my work only to be met with a fire that seemed to ignite underneath my eyeball and burn for hours. I was sure I would be blinded for life.

Whenever I thought we might have time to ourselves between preparing meals, my mother would drag me around the house and we would make the beds, sweep, and dust. My father and brother dirtied everything and we dutifully followed behind cleaning it up. On the weekends we rose at dawn to weed the garden so our vegetables wouldn’t be ruined, washed the laundry, and swept the porches and floors again. On Sundays we traveled to the market to sell our peppers to the merchants who would distribute them all across France and to buy food for the week. I looked forward to each Sunday, if only for a break in a routine that I grew to resent almost as much as I resented my mother. I despised working in the garden the most. As the sun rose, we hunched over pulling out weeds, my mother going into near hysterics when I inevitably pulled out a carrot or beet. “Pay attention! That could have been your dinner,” she screamed.

“They all look the same!” I complained back to her, my legs cramping as I stood to brush off the dirt caked on my knees. I looked down at my hands, which had dirt underneath the fingernails, and I knew that as soon as the dirt finally disappeared it would be time to come back into the garden and my fingernails would be dirtied again. I wiped my hands together hopelessly, and untied my bonnet in order to lift my sweaty hair away from my neck. “Put your bonnet back on,” my mother said without looking up. “But it’s so hot,” I whined. How had she seen me? “If you don’t wear your bonnet, you will get sunburned and ruin your skin,” she declared, her arms moving down the row of weeds. “And the sun will lighten your hair, then once you stay inside during the winter your hair will grow in darker, leaving it half light and half dark and you’ll look despicable. Once you’re married you can burn your skin and lighten your hair to your heart’s content, but until then you need to take care of yourself.”

My mother was obsessed with looking proper for the sole purpose of attracting a stable husband. I peered at her, scrutinizing her weathered look from sunburned skin, her dry hair, her yellowed teeth that she long ago stopped taking care of. Looking proper didn’t apply to her because both my brother and I were supposed to correct the mistakes that she had made. It was no secret that she had expected a certain kind of life. She was an educated woman, able to read and write, which was something that had been very important to my grandparents, may they rest in peace. Their philosophy had been to give their only daughter the freedom to make her own decisions, with the belief that it would lead her to happiness. It didn’t and she vowed not to raise us the same way.

My mother had been overly praised as a child and thought that the world would bend to her will. She never would have pictured herself weeding in the hot sun behind a tiny home with a roof that leaked when the heavy rains came through. My father swept her off her feet with his grand ideas. She looked into the future and saw the two of them acquiring much land and supervising farmhands, not tilling the earth with their own hands. Only years into the marriage, and after the birth of my brother and me, did she see that while my father’s ideas were bountiful, they were never put into action. They spent more than they had, with the thought that in a few years when one of these ideas became a reality, they could easily pay off the many debts they had been acquiring. I could see for myself that merchants would no longer offer them credit because they also knew by now that my father would never attempt to see any of his moneymaking ideas through.

I knew I was supposed to do as Maman said, that I should look forward to growing up and marrying a successful farmer, but it was the last thing I wanted for myself. I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life waiting on my father and brother, and then having to do the same thing for my husband and sons. I wanted to be able to do something more important than clean, and to afford to have someone else make all of my meals. I felt sorry for my mother, pulling weeds constantly. As the sun beat down on me, I realized my mother and I had one thing in common—I would do whatever it took not to have her life.

1859

I wasn’t always filled with such anxiety. The inescapable need for perfection was cultivated during many years of training—just as my body was strengthened to complete a flawless pirouette, my mind underwent vigorous instruction until I believed that I was better than all others and entitled to nothing short of the riches of an empress. Yet it was no secret that I could be dethroned without a second thought. My success was nothing but an illusion, which I find especially ironic because I was not born into such complications. I sought them out.

At the age of twelve, when all the girls around me seemed to be blossoming, I was painfully average. Others received praise for their looks and talents, while I faded into the background. Once in a while someone would compliment my startling green eyes, but this only happened when there was no one else in the vicinity and nothing else to focus on. And, believe me, one had to put quite a bit of focus into the task of taking notice. They had to overlook my gangly, awkward body, my clothes that always seemed to attract dirt, my drab, brown hair that always managed to become unruly. It was a wonder to me how other girls seemed to not have to give their hair a second thought. I couldn’t stop staring at the locks that cascaded over their shoulders in one fluid motion like corn silk. My wavy hair seemed to feed off of hairbrushes, growing larger and larger with each stroke. Like a horse running wild, I could not control it so I chose instead to suppress it under limp bonnets.

My hair was only the start of my ordinary existence. I grew taller than most girls my age, but not so tall that I drew attention, only tall enough to look clumsy by comparison. I loathed running into the Neville family at the market. Madame Neville had given birth to a staggering number of children, ten the last time I counted and all girls, all names beginning with N—Nathalie, Nicole, Naomi, and so on. I was sure they would run out of N names if she didn’t stop having children. The Neville girls were tiny, so tiny that they drew crowds as they followed behind their mother like a row of ducklings with shiny white heads of hair. I hated when my mother would stop to pay her respects to Madame Neville and I would find myself stuck in the middle of the group, my head rising above the girls like a large, scruffy dog amongst a litter of kittens. The only company I kept was my mother’s, with just one brother who mimicked my father’s apathy toward me as if neither could be bothered with the trivial thoughts of a girl, and thus I really had no idea how to talk to children my own age. When passersby would stop and coo that the Neville girls looked just like a group of porcelain dolls, my face would grow red and I would stare down at my shoes. I remember peering over at Madame Neville, who basked in the glow of the compliments, a baby thrust onto her hip, and noticing how her body resembled a pyramid, becoming wider and wider until her bottom sagged down so low that it seemed it would surely touch the ground. I thought with some satisfaction that these tiny girls would grow to be only as tall as their mother. They wouldn’t be able to grow higher, so they would grow wider until each of the little dolls resembled walking pyramids as well.

While I was much too shy and proper to have said such a terrible thing aloud, I did constantly think terrible thoughts of others. Perhaps it was from being overlooked so often; I had nothing else to do but observe those around me and find faults to rival the compliments they were given. If a girl received praise for her exquisite needlework while I tried to hide the knots that formed in mine, I would shrug my shoulders and console myself with the thought that of course her needlework was perfect, she had such large bug eyes that the tiny stitches must surely be magnified to her!

Such thoughts entertained me as I began morning chores each day at our tiny farmhouse which meandered off the path from the small winding streets of our little town of Espelette. Espelette was as painfully ordinary as myself, with only its spicy pepper crop bringing it any recognition. Locals called it the fiery side of France, although there was nothing sizzling about it in my opinion. My father grew hot peppers, just like every other farmer in the town.

“Alexandrie, don’t let the eggs sit over the fire, keep stirring them so they scramble properly,” my mother’s shrill voice interrupted my thoughts as she cut thick slices of bread, spreading butter over them. “Your father and brother have a long day of work ahead and they need a hearty breakfast.”

As I whipped the fork through the eggs, I paused to watch them puff up, letting a huge bubble form and then poking my fork in the center so it burst.

“Alexandrie, I told you if you let the eggs sit they become rubbery,” my mother said, exasperated.

“You should know these things by now,” she added while guiding my hands. “I can only pray that one day you’ll make a good wife.” I saw how effortless it was for her and wished she would just finish it since her arms were so much larger and stronger than mine.

“What difference does it really make?” I complained. “We spend all of this time making breakfast and then Denis and Papa rush in and eat it in minutes. Why can’t we eat before them so we can have eggs too? Most of the time there isn’t anything left for us but a slice of bread.”

“If we eat first, then there might not be enough for them,” she told me in a singsong voice that made me wonder how she could sound so happy about something that was so unfair.

I felt as if we lived in the kitchen. As soon as one meal ended we had to begin preparing for the next. We never stopped throughout the day. In between our kitchen duties we would hang freshly harvested peppers on our front and back porches to dry. We worked quickly, throwing the dried ones in a bag to be ground into a fine powder. I spent each afternoon hunched over the funny red vegetables, smashing them into dust to be sold at the market, all the while careful not to touch my face. I once made the mistake of rubbing my eye in the midst of my work only to be met with a fire that seemed to ignite underneath my eyeball and burn for hours. I was sure I would be blinded for life.

Whenever I thought we might have time to ourselves between preparing meals, my mother would drag me around the house and we would make the beds, sweep, and dust. My father and brother dirtied everything and we dutifully followed behind cleaning it up. On the weekends we rose at dawn to weed the garden so our vegetables wouldn’t be ruined, washed the laundry, and swept the porches and floors again. On Sundays we traveled to the market to sell our peppers to the merchants who would distribute them all across France and to buy food for the week. I looked forward to each Sunday, if only for a break in a routine that I grew to resent almost as much as I resented my mother. I despised working in the garden the most. As the sun rose, we hunched over pulling out weeds, my mother going into near hysterics when I inevitably pulled out a carrot or beet. “Pay attention! That could have been your dinner,” she screamed.

“They all look the same!” I complained back to her, my legs cramping as I stood to brush off the dirt caked on my knees. I looked down at my hands, which had dirt underneath the fingernails, and I knew that as soon as the dirt finally disappeared it would be time to come back into the garden and my fingernails would be dirtied again. I wiped my hands together hopelessly, and untied my bonnet in order to lift my sweaty hair away from my neck. “Put your bonnet back on,” my mother said without looking up. “But it’s so hot,” I whined. How had she seen me? “If you don’t wear your bonnet, you will get sunburned and ruin your skin,” she declared, her arms moving down the row of weeds. “And the sun will lighten your hair, then once you stay inside during the winter your hair will grow in darker, leaving it half light and half dark and you’ll look despicable. Once you’re married you can burn your skin and lighten your hair to your heart’s content, but until then you need to take care of yourself.”

My mother was obsessed with looking proper for the sole purpose of attracting a stable husband. I peered at her, scrutinizing her weathered look from sunburned skin, her dry hair, her yellowed teeth that she long ago stopped taking care of. Looking proper didn’t apply to her because both my brother and I were supposed to correct the mistakes that she had made. It was no secret that she had expected a certain kind of life. She was an educated woman, able to read and write, which was something that had been very important to my grandparents, may they rest in peace. Their philosophy had been to give their only daughter the freedom to make her own decisions, with the belief that it would lead her to happiness. It didn’t and she vowed not to raise us the same way.

My mother had been overly praised as a child and thought that the world would bend to her will. She never would have pictured herself weeding in the hot sun behind a tiny home with a roof that leaked when the heavy rains came through. My father swept her off her feet with his grand ideas. She looked into the future and saw the two of them acquiring much land and supervising farmhands, not tilling the earth with their own hands. Only years into the marriage, and after the birth of my brother and me, did she see that while my father’s ideas were bountiful, they were never put into action. They spent more than they had, with the thought that in a few years when one of these ideas became a reality, they could easily pay off the many debts they had been acquiring. I could see for myself that merchants would no longer offer them credit because they also knew by now that my father would never attempt to see any of his moneymaking ideas through.

I knew I was supposed to do as Maman said, that I should look forward to growing up and marrying a successful farmer, but it was the last thing I wanted for myself. I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life waiting on my father and brother, and then having to do the same thing for my husband and sons. I wanted to be able to do something more important than clean, and to afford to have someone else make all of my meals. I felt sorry for my mother, pulling weeds constantly. As the sun beat down on me, I realized my mother and I had one thing in common—I would do whatever it took not to have her life.

Recenzii

“A thoroughly engrossing and informative story…Degas’ paintings of the Paris Opera Ballet corps come to life in all their freshness and immediacy.”—Historical Novels Review

“Like Tracy Chevalier, Wagner imagines how layers of meaning pervade works of art, but her real forte is detailing the sexual politics of poverty and evoking the rivalry among dancers, especially between stars and the newcomers who wish to replace them. Wagner’s… abandonment of the masterpiece-in-the-making formula is a nice turn.”—Publishers Weekly

“First-time novelist Wagner skillfully compresses the war into a series of brief letters in this engaging tale illuminating the dark side of French society high and low. With appearances by Degas’ peers Cezanne and Monet, this fascinating visit to a bygone world of art and sex, war and love will draw many.”—Booklist

“Like Tracy Chevalier, Wagner imagines how layers of meaning pervade works of art, but her real forte is detailing the sexual politics of poverty and evoking the rivalry among dancers, especially between stars and the newcomers who wish to replace them. Wagner’s… abandonment of the masterpiece-in-the-making formula is a nice turn.”—Publishers Weekly

“First-time novelist Wagner skillfully compresses the war into a series of brief letters in this engaging tale illuminating the dark side of French society high and low. With appearances by Degas’ peers Cezanne and Monet, this fascinating visit to a bygone world of art and sex, war and love will draw many.”—Booklist

Descriere

With this fresh and vibrantly imagined portrait of the Impressionist artist Edgar Degas, readers are transported to Paris as a young Parisian ballerina tells a story of great love, great art--and the most painful choices of the heart.