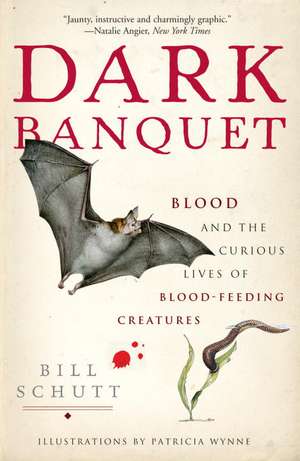

Dark Banquet: Blood and the Curious Lives of Blood-Feeding Creatures

Autor Bill Schutten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2009

—San Francisco Chronicle

For centuries, blood feeders have inhabited our nightmares and horror stories, as well as the shadowy realms of scientific knowledge. In Dark Banquet, zoologist Bill Schutt takes us on a fascinating voyage into the world of some of nature’s strangest creatures–the sanguivores. Using a sharp eye and mordant wit, Schutt makes a remarkably persuasive case that blood feeders, from bats to bedbugs, are as deserving of our curiosity as warmer and fuzzier species are–and that many of them are even worthy of conservation.

Enlightening and alarming, Dark Banquet peers into a part of the natural world to which we are, through our blood, inextricably linked.

"Dark Banquet is an amazing account of all those creatures that most of us consider really creepy! But author Bill Schutt doesn’t, and actually embraces these critters and their bloodthirsty lifestyles. It’s great to see such wonderful animal research in a reader-friendly form. After finishing the book, you’ll have a lot to discuss at your next dinner party!"

—Jack Hanna, director emeritus, Columbus Zoo, and host of television’s Emmy Award—winning series Into the Wild

"[A] passionate defense of bloodsuckers from the leech to the candiru."

—Discover

Preț: 112.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.49€ • 22.50$ • 17.89£

21.49€ • 22.50$ • 17.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307381132

ISBN-10: 0307381137

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 54 LINE DRAWINGS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307381137

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 54 LINE DRAWINGS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Bill Schutt is a vertebrate zoologist and author of six nonfiction and fiction books, including the New York Times Editors’ Choice Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History. Recently retired from his post as professor of biology at LIU Post, he is a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History, where he has studied bats all over the world. His research has been featured in Natural History magazine as well as in the New York Times, Newsday, the Economist, and Discover.

Extras

1. WALLERFIELD

( Nine years earlier )

The ceiling tiles in the abandoned icehouse had fallen long ago, transforming the floor of the cavernous building into a debris-strewn obstacle course.

“Hey, it’s squishy,” I said, stepping gingerly onto a slime-coated chunk just inside the doorway. “Some sort of foam.”

“It’s probably just asbestos.”

My wife, Janet, was a terrific field assistant, but I could tell that this place was already giving her a serious case of the creeps.

“Yes, but with a protective coating of bat shit,” I added, trying to cheer her up. “Let’s check it out.”

Wallerfield, in north-central Trinidad, had been a center for American military operations in the southern Atlantic during World War II. The land on which it had been built became part of the same Lend-Lease program that had brought Churchill’s shell-shocked government fifty outdated American destroyers. Once it had been the largest and busiest air base in the world, but the English were long gone, as were the Yanks (most of them anyway), and now Wallerfield was an overgrown ruin. Row upon row of prefab buildings had either been carted off in pieces by the locals or reclaimed by the scrubby forests of Trinidad’s Central Plain, but because of its cement construction the icehouse was one of the few buildings still standing. Stark white below a mantle of tangled green, the icehouse belonged to the bats—tens of thousands of them.

With help from the Trinidad’s Ministry of Agriculture we’d been collecting vampire bats around the island for nearly two weeks—and things had gone incredibly well. So well, in fact, that when our friend Farouk suggested that we visit the cavernous and somewhat notorious ruins of Wallerfield, Janet and I jumped at the chance to accompany him.

The icehouse wasn’t completely dark yet. Daylight streamed through a window frame that in all likelihood hadn’t held glass in fifty years. The light fell obliquely onto the floor, illuminating the base of a cement pillar that rose a dozen feet to the ceiling. The only movement was from the dust that swirled into and out of the sunlight. We passed single file through a shaft of motes before continuing on into deepening shadow. The room we were crossing was huge, perhaps two hundred feet long and half as wide, and it took us a good five minutes to pick our way across the slippery rubble.

We stopped at what looked to be a high doorway leading into a smaller room, around fifteen feet square. But instead of entering, our companion put his arm out, stopping us before we could go farther.

“You don’t want to walk in there, boy.” The Indo-Trini accent belonged to Farouk Muradali, head of his government’s Anti-Rabies Unit. Farouk would also become my mentor for all things related to Trinidadian bats and a collaborator on a project to study quadrupedal locomotion in vampire bats.

“Why’s that, Farouk?” I asked, as Janet and I flicked on our headlamps.

“That is not a room,” he said.

As I trained my beam inside the chamber I couldn’t help noticing that the floor had a weird shine to it. “What the—?”

“It’s an elevator shaft.”

“A what?” Janet said, pulling up beside me.

I kicked in a small piece of debris past the threshold and it hit the dark surface with a plop. “Jesus, it’s completely filled with water!”

Janet edged closer, the light from her headlamp focused at a point just beyond the doorway. “That is not water,” she said.

The “floor” of the shaft was a debris-strewn swamp. There was indeed some type of filthy, tar black liquid filling the shaft, but Janet was right—it certainly wasn’t water.

Scattered across the surface of this scuzzy brew were tattered blocks of dark-stained ceiling material as well as unidentifiable rubbish that had been chucked in over the past fifty years. The scariest thing to me was that all of it looked remarkably like the rubble-littered cement floor we were currently standing on.

“A group came in here to see the bats some time ago and one of them, a woman, turned up missing.” Farouk pointed to a spot near where the real floor ended. “They found her there, clutching onto the ledge. Only her head and arms were above the surface.”

I could see my wife give a shudder and she took several steps back from the edge.

Carefully, I moved a bit closer, kneeling at the entrance of the shaft. It still looked like a solid surface. “Farouk. How deep is this friggin’ thing?”

“It goes down several floors,” he said, a bit too matter-of-factly. “And off the main shaft—a maze of side tunnels.”

As the light from my headlamp moved across the glistening surface, something the size of a football catapulted itself through the beam. My reflexes send me backward onto my butt as the object landed with a loud splash. Three headlamp beams hit the impact point, but by then whatever it was had disappeared below the ink black sludge.

“What the hell was that?” Janet asked, her voice an alarmed whisper.

“I think it was a toad,” I responded. “A big mother.” And as I turned back to Farouk, he nodded in agreement.

“They feed on the bats that fall in from above,” he said. “The babies and the weak ones.”

With that, the Trinidadian directed his light upward, until we could just make out the ceiling of the elevator shaft, twenty feet from where we stood.

As I squinted into the darkness, Farouk moved away, motioning us to follow. “You can see the bats much better from upstairs.”

Our companion stopped before a narrow stairway leading to the second floor. The railings had either collapsed long ago or been carted off by the locals, leaving only small circular holes in the cement. Three separate beams moved across the steps, each of us searching for any indication that the stairs might not be safe.

I was on the verge of saying something about the strong smell of ammonia when I heard Farouk’s voice. His tone had grown more serious. “Janet, maybe you should remain down here.”

“Yeah, that’s gonna happen,” I said with a laugh. My wife had recently spent three hours exploring Caura Cave, the floor of which was slick with guano and crawling with enormous roaches, all without a complaint. Only later did I learn that she had had a migraine the entire time. So it came as no shock when she politely waved off Farouk’s chivalrous suggestion and began climbing the darkened stairs.

One year earlier, at a symposium on bat research, I had gotten up the courage to approach Arthur M. Greenhall, one of the world’s leading authorities on vampire bats. I was in the second year of a Ph.D. program at Cornell and like many grad students I was sniffing around for a dissertation project. (Luckily, the head of my graduate committee, John Hermanson wasn’t one of those guys who handed you a ready-made project, although I had to admit there were some days when I wished he had.) By this time, Greenhall was in his midseventies but he was still vibrant and inquisitive—as excited about science as anyone I had ever met.

Born and raised in New York City, he’d had a storied career. In 1933 Greenhall and Raymond Ditmars, his mentor at the New York Zoological Park, had collected the first vampire bat ever to be exhibited alive in the United States. It was a female that turned out to be pregnant, delivering a vampire bat pup several months later. The following year, the young scientist arrived in Trinidad during the height of a major rabies outbreak. He studied the deadly virus and its blood-feeding vector with local scientists and collected additional vampire bats. On his return to the United States, he found he had more specimens than his zoo could display or handle. Greenhall solved the problem by keeping twenty of the creatures in his New York City apartment for two years.

During a break between research presentations that day, I had spoken to several noted bat biologists about possible differences in behavior or anatomy between the three vampire bat genera, Desmodus, Diaemus, and Diphylla. From previous studies I had learned that Desmodus, the common vampire bat, exhibited an incredible array of unbatlike behaviors, including a spiderlike agility on the ground. Just as interesting to me was the way Desmodus initiated flight. In virtually all nonvampire bats, takeoff began with a wing beat that accelerated the animal away from the wall, ceiling, or branch from which it hung. Heavily loaded down after a blood meal, Desmodus was renowned for its ability to catapult itself into flight from the ground by doing a sort of super push-up.

“Maybe,” I proposed, “the other vampire bats, Diaemus or Diphylla, did things a little differently.”

“Not likely,” I was told more than once. “A vampire bat is a vampire bat is a vampire bat,” chanted several bat scientists. I wondered if there might be a secret handshake that went along with this information, one that I had yet to learn.

After introducing myself to Greenhall, I told him what the bat researchers had said, adding that I found their responses puzzling.

“Why’s that?” the vampire maven responded. “Well, because the rule of competitive exclusion says that if similar animals are competing for the same resource, in this instance blood, then one of three things will happen. One of the animals will relocate. One of them will go extinct. Or one of them will evolve changes, reducing the competition for that resource.”

“And since vampire bat genera have overlapping ranges . . . ?” Greenhall interjected, setting me up beautifully for the punch line. “They've got to be different.”

The old scientist gave me a sly smile. “You’re on to something, kid,” he said. Then he lowered his voice. “Now get on the stick before someone else gets to it first.”

It had taken me six months to “get on the stick,” but by then my fellow Cornell grad students, Young-Hui Chang and Dennis Cullinane and I had followed our mentor John Bertram’s lead and built a miniature version of a force platform, a device that could measure the forces applied to a flat metal plate as a creature (in this case, a vampire bat) moved across it. By synchronizing the force platform signals with high-speed cinematography, we planned to see if there would be measurable differences in the flight-initiating jumps of Desmodus rotundus and Diaemus youngi, the two vampires I would collect and bring back from Trinidad.

Not long after arriving in Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, Port of Spain, I told Farouk what a pain it had been for us to machine the metal components of our force platform, get the electronics working just right, and then write the data-acquisition software. He stood by patiently as I tooted my own horn, polished it a bit, then tooted some more. Finally, I ran out of intricate gear to describe (or it might have been air).

“It won’t work,” Farouk said, matter-of-factly.

“Excuse me?” I replied, my voice cracking like a twelve-year- old boy’s.

“Your experiment won’t work.”

Now I was getting visibly annoyed. Hadn’t I just told him how much time, effort, and brainpower had gone into this project?

“Of course it’ll work.” I was getting frantic now.

The Trinidadian said nothing.

“Why won’t it work?”

Muradali put his hand on my shoulder and smiled. “Because Diaemus youngi doesn’t jump.”

“Oh,” I replied, sheepishly. “Right.”

The light from Janet’s headlamp swept upward from the bottom of the empty elevator shaft (now below us) to the ceiling. “So where are all the—” Her beam had stopped tracking abruptly.

Illuminated at the top of the chamber were three circular clusters, each composed of a dozen or so black silhouettes, arranged concentrically. They hung silently, reminding me of giant Christmas tree ornaments. Suddenly, one of the fusiform shapes unfurled, revealing wings nearly two feet across.

“Phyllostomus hastatus,” Farouk whispered. “The second-largest bat in Trinidad.”

“Crawling mother of Waldo,” I muttered, and Muradali threw me a confused look.

“Don’t mind him,” Janet explained, keeping her light trained on the bats. “He gets all scientific when he’s excited.”

Muradali nodded politely, then began assembling an object that looked suspiciously like a drawstring-equipped butterfly net at the end of a four-foot pole.

I shot him a quizzical look. “A butterfly net?”

“Swoop net,” Muradali corrected, handing it to Janet.

Farouk nodded toward the net, then shined his light up at a cluster of bats. “To catch the ones closest to the elevator door, you lean out over the edge while someone holds your belt or backpack.”

Janet glanced up at the bats, then quickly shoved the net into my hands. Possibly she’d had the same vision that I’d just had, of tumbling down a concrete-lined abyss with nothing except years of rainwater, bat guano, and asbestos to soften the fall.

As I moved into the doorway, it was impossible to chase away the image of that poor woman, stepping off the solid concrete floor and into a bottomless pit of bat-shit soup. “Thanks, hon,” I said.

Janet only smiled.

“We’ll leave these bats alone,” Muradali said, moving away from the shaft.

As we quickly followed him, I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I’d been holding. “Can we catch vampires like this?” I asked, suddenly feeling a bit braver and taking a few swings at some phantom air bats.

“No,” he replied, picking his way through the debris. “Too smart.”

Later, the scientist explained that early efforts to eradicate vampire bats had resulted in the deaths of thousands of non-blood-feeding species. In 1941 Captain Lloyd Gates was placed in charge of protecting the American forces stationed at Wallerfield from the twin threat of mosquitoes and vampire bats. Gates’s less-than-subtle response to the bat problem was to have his men use dynamite and poison gas in caves known to contain bat roosts. Flamethrowers became a popular alternative, but still the vampires persisted, as did their attacks upon the encroaching military men. Also hard hit was the increasing population of locals who had been drawn to the region for the income the base provided. As a result, thousands upon thousands of non-blood-feeding bats were blown up, poisoned, or incinerated. Even worse, these bat eradication techniques were apparently so appealing that over eight thousand caves in post–World War II Brazil were similarly destroyed.

Farouk recounted how he and vampire bat expert Rexford Lord had been sent to Brazil to pick up some tips on eradicating Desmodus from the antirabies groups working there.

“These guys took us to a cave. Then they rolled out a big tank of propane and wired it up with an old-fashioned camera flash, running the wires out the cave entrance.”

He described how everyone waited outside the cave entrance while one of the Brazilians opened up the gas-tank valve.

“Must have been the new guy,” I added.

From the Hardcover edition.

( Nine years earlier )

The ceiling tiles in the abandoned icehouse had fallen long ago, transforming the floor of the cavernous building into a debris-strewn obstacle course.

“Hey, it’s squishy,” I said, stepping gingerly onto a slime-coated chunk just inside the doorway. “Some sort of foam.”

“It’s probably just asbestos.”

My wife, Janet, was a terrific field assistant, but I could tell that this place was already giving her a serious case of the creeps.

“Yes, but with a protective coating of bat shit,” I added, trying to cheer her up. “Let’s check it out.”

Wallerfield, in north-central Trinidad, had been a center for American military operations in the southern Atlantic during World War II. The land on which it had been built became part of the same Lend-Lease program that had brought Churchill’s shell-shocked government fifty outdated American destroyers. Once it had been the largest and busiest air base in the world, but the English were long gone, as were the Yanks (most of them anyway), and now Wallerfield was an overgrown ruin. Row upon row of prefab buildings had either been carted off in pieces by the locals or reclaimed by the scrubby forests of Trinidad’s Central Plain, but because of its cement construction the icehouse was one of the few buildings still standing. Stark white below a mantle of tangled green, the icehouse belonged to the bats—tens of thousands of them.

With help from the Trinidad’s Ministry of Agriculture we’d been collecting vampire bats around the island for nearly two weeks—and things had gone incredibly well. So well, in fact, that when our friend Farouk suggested that we visit the cavernous and somewhat notorious ruins of Wallerfield, Janet and I jumped at the chance to accompany him.

The icehouse wasn’t completely dark yet. Daylight streamed through a window frame that in all likelihood hadn’t held glass in fifty years. The light fell obliquely onto the floor, illuminating the base of a cement pillar that rose a dozen feet to the ceiling. The only movement was from the dust that swirled into and out of the sunlight. We passed single file through a shaft of motes before continuing on into deepening shadow. The room we were crossing was huge, perhaps two hundred feet long and half as wide, and it took us a good five minutes to pick our way across the slippery rubble.

We stopped at what looked to be a high doorway leading into a smaller room, around fifteen feet square. But instead of entering, our companion put his arm out, stopping us before we could go farther.

“You don’t want to walk in there, boy.” The Indo-Trini accent belonged to Farouk Muradali, head of his government’s Anti-Rabies Unit. Farouk would also become my mentor for all things related to Trinidadian bats and a collaborator on a project to study quadrupedal locomotion in vampire bats.

“Why’s that, Farouk?” I asked, as Janet and I flicked on our headlamps.

“That is not a room,” he said.

As I trained my beam inside the chamber I couldn’t help noticing that the floor had a weird shine to it. “What the—?”

“It’s an elevator shaft.”

“A what?” Janet said, pulling up beside me.

I kicked in a small piece of debris past the threshold and it hit the dark surface with a plop. “Jesus, it’s completely filled with water!”

Janet edged closer, the light from her headlamp focused at a point just beyond the doorway. “That is not water,” she said.

The “floor” of the shaft was a debris-strewn swamp. There was indeed some type of filthy, tar black liquid filling the shaft, but Janet was right—it certainly wasn’t water.

Scattered across the surface of this scuzzy brew were tattered blocks of dark-stained ceiling material as well as unidentifiable rubbish that had been chucked in over the past fifty years. The scariest thing to me was that all of it looked remarkably like the rubble-littered cement floor we were currently standing on.

“A group came in here to see the bats some time ago and one of them, a woman, turned up missing.” Farouk pointed to a spot near where the real floor ended. “They found her there, clutching onto the ledge. Only her head and arms were above the surface.”

I could see my wife give a shudder and she took several steps back from the edge.

Carefully, I moved a bit closer, kneeling at the entrance of the shaft. It still looked like a solid surface. “Farouk. How deep is this friggin’ thing?”

“It goes down several floors,” he said, a bit too matter-of-factly. “And off the main shaft—a maze of side tunnels.”

As the light from my headlamp moved across the glistening surface, something the size of a football catapulted itself through the beam. My reflexes send me backward onto my butt as the object landed with a loud splash. Three headlamp beams hit the impact point, but by then whatever it was had disappeared below the ink black sludge.

“What the hell was that?” Janet asked, her voice an alarmed whisper.

“I think it was a toad,” I responded. “A big mother.” And as I turned back to Farouk, he nodded in agreement.

“They feed on the bats that fall in from above,” he said. “The babies and the weak ones.”

With that, the Trinidadian directed his light upward, until we could just make out the ceiling of the elevator shaft, twenty feet from where we stood.

As I squinted into the darkness, Farouk moved away, motioning us to follow. “You can see the bats much better from upstairs.”

Our companion stopped before a narrow stairway leading to the second floor. The railings had either collapsed long ago or been carted off by the locals, leaving only small circular holes in the cement. Three separate beams moved across the steps, each of us searching for any indication that the stairs might not be safe.

I was on the verge of saying something about the strong smell of ammonia when I heard Farouk’s voice. His tone had grown more serious. “Janet, maybe you should remain down here.”

“Yeah, that’s gonna happen,” I said with a laugh. My wife had recently spent three hours exploring Caura Cave, the floor of which was slick with guano and crawling with enormous roaches, all without a complaint. Only later did I learn that she had had a migraine the entire time. So it came as no shock when she politely waved off Farouk’s chivalrous suggestion and began climbing the darkened stairs.

One year earlier, at a symposium on bat research, I had gotten up the courage to approach Arthur M. Greenhall, one of the world’s leading authorities on vampire bats. I was in the second year of a Ph.D. program at Cornell and like many grad students I was sniffing around for a dissertation project. (Luckily, the head of my graduate committee, John Hermanson wasn’t one of those guys who handed you a ready-made project, although I had to admit there were some days when I wished he had.) By this time, Greenhall was in his midseventies but he was still vibrant and inquisitive—as excited about science as anyone I had ever met.

Born and raised in New York City, he’d had a storied career. In 1933 Greenhall and Raymond Ditmars, his mentor at the New York Zoological Park, had collected the first vampire bat ever to be exhibited alive in the United States. It was a female that turned out to be pregnant, delivering a vampire bat pup several months later. The following year, the young scientist arrived in Trinidad during the height of a major rabies outbreak. He studied the deadly virus and its blood-feeding vector with local scientists and collected additional vampire bats. On his return to the United States, he found he had more specimens than his zoo could display or handle. Greenhall solved the problem by keeping twenty of the creatures in his New York City apartment for two years.

During a break between research presentations that day, I had spoken to several noted bat biologists about possible differences in behavior or anatomy between the three vampire bat genera, Desmodus, Diaemus, and Diphylla. From previous studies I had learned that Desmodus, the common vampire bat, exhibited an incredible array of unbatlike behaviors, including a spiderlike agility on the ground. Just as interesting to me was the way Desmodus initiated flight. In virtually all nonvampire bats, takeoff began with a wing beat that accelerated the animal away from the wall, ceiling, or branch from which it hung. Heavily loaded down after a blood meal, Desmodus was renowned for its ability to catapult itself into flight from the ground by doing a sort of super push-up.

“Maybe,” I proposed, “the other vampire bats, Diaemus or Diphylla, did things a little differently.”

“Not likely,” I was told more than once. “A vampire bat is a vampire bat is a vampire bat,” chanted several bat scientists. I wondered if there might be a secret handshake that went along with this information, one that I had yet to learn.

After introducing myself to Greenhall, I told him what the bat researchers had said, adding that I found their responses puzzling.

“Why’s that?” the vampire maven responded. “Well, because the rule of competitive exclusion says that if similar animals are competing for the same resource, in this instance blood, then one of three things will happen. One of the animals will relocate. One of them will go extinct. Or one of them will evolve changes, reducing the competition for that resource.”

“And since vampire bat genera have overlapping ranges . . . ?” Greenhall interjected, setting me up beautifully for the punch line. “They've got to be different.”

The old scientist gave me a sly smile. “You’re on to something, kid,” he said. Then he lowered his voice. “Now get on the stick before someone else gets to it first.”

It had taken me six months to “get on the stick,” but by then my fellow Cornell grad students, Young-Hui Chang and Dennis Cullinane and I had followed our mentor John Bertram’s lead and built a miniature version of a force platform, a device that could measure the forces applied to a flat metal plate as a creature (in this case, a vampire bat) moved across it. By synchronizing the force platform signals with high-speed cinematography, we planned to see if there would be measurable differences in the flight-initiating jumps of Desmodus rotundus and Diaemus youngi, the two vampires I would collect and bring back from Trinidad.

Not long after arriving in Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, Port of Spain, I told Farouk what a pain it had been for us to machine the metal components of our force platform, get the electronics working just right, and then write the data-acquisition software. He stood by patiently as I tooted my own horn, polished it a bit, then tooted some more. Finally, I ran out of intricate gear to describe (or it might have been air).

“It won’t work,” Farouk said, matter-of-factly.

“Excuse me?” I replied, my voice cracking like a twelve-year- old boy’s.

“Your experiment won’t work.”

Now I was getting visibly annoyed. Hadn’t I just told him how much time, effort, and brainpower had gone into this project?

“Of course it’ll work.” I was getting frantic now.

The Trinidadian said nothing.

“Why won’t it work?”

Muradali put his hand on my shoulder and smiled. “Because Diaemus youngi doesn’t jump.”

“Oh,” I replied, sheepishly. “Right.”

The light from Janet’s headlamp swept upward from the bottom of the empty elevator shaft (now below us) to the ceiling. “So where are all the—” Her beam had stopped tracking abruptly.

Illuminated at the top of the chamber were three circular clusters, each composed of a dozen or so black silhouettes, arranged concentrically. They hung silently, reminding me of giant Christmas tree ornaments. Suddenly, one of the fusiform shapes unfurled, revealing wings nearly two feet across.

“Phyllostomus hastatus,” Farouk whispered. “The second-largest bat in Trinidad.”

“Crawling mother of Waldo,” I muttered, and Muradali threw me a confused look.

“Don’t mind him,” Janet explained, keeping her light trained on the bats. “He gets all scientific when he’s excited.”

Muradali nodded politely, then began assembling an object that looked suspiciously like a drawstring-equipped butterfly net at the end of a four-foot pole.

I shot him a quizzical look. “A butterfly net?”

“Swoop net,” Muradali corrected, handing it to Janet.

Farouk nodded toward the net, then shined his light up at a cluster of bats. “To catch the ones closest to the elevator door, you lean out over the edge while someone holds your belt or backpack.”

Janet glanced up at the bats, then quickly shoved the net into my hands. Possibly she’d had the same vision that I’d just had, of tumbling down a concrete-lined abyss with nothing except years of rainwater, bat guano, and asbestos to soften the fall.

As I moved into the doorway, it was impossible to chase away the image of that poor woman, stepping off the solid concrete floor and into a bottomless pit of bat-shit soup. “Thanks, hon,” I said.

Janet only smiled.

“We’ll leave these bats alone,” Muradali said, moving away from the shaft.

As we quickly followed him, I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I’d been holding. “Can we catch vampires like this?” I asked, suddenly feeling a bit braver and taking a few swings at some phantom air bats.

“No,” he replied, picking his way through the debris. “Too smart.”

Later, the scientist explained that early efforts to eradicate vampire bats had resulted in the deaths of thousands of non-blood-feeding species. In 1941 Captain Lloyd Gates was placed in charge of protecting the American forces stationed at Wallerfield from the twin threat of mosquitoes and vampire bats. Gates’s less-than-subtle response to the bat problem was to have his men use dynamite and poison gas in caves known to contain bat roosts. Flamethrowers became a popular alternative, but still the vampires persisted, as did their attacks upon the encroaching military men. Also hard hit was the increasing population of locals who had been drawn to the region for the income the base provided. As a result, thousands upon thousands of non-blood-feeding bats were blown up, poisoned, or incinerated. Even worse, these bat eradication techniques were apparently so appealing that over eight thousand caves in post–World War II Brazil were similarly destroyed.

Farouk recounted how he and vampire bat expert Rexford Lord had been sent to Brazil to pick up some tips on eradicating Desmodus from the antirabies groups working there.

“These guys took us to a cave. Then they rolled out a big tank of propane and wired it up with an old-fashioned camera flash, running the wires out the cave entrance.”

He described how everyone waited outside the cave entrance while one of the Brazilians opened up the gas-tank valve.

“Must have been the new guy,” I added.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A jaunty, instructive and charmingly graphic look at nature’s born phlebotomists – creatures from wildly different twigs of the phylogenetic tree that all happen to share a fondness for blood.”

—The New York Times

“[P]rofiles some of the animal kingdom's dedicated bloodsuckers, from vampire bats and the dreaded candiru catfish to the not-so-dreaded vampire finch….Schutt is an engaging writer.”

—Washington Post Book World

"Zoologist Bill Schutt, through witty, informed writing, transforms bloodsuckers into enticing creatures."

—Metro (NY)

“With great scientific accuracy (backed up by extensive notes and a bibliography), text couched in layman’s terms, and a sense of breathless discovery, Schutt will make blood feeding just another choice on the culinary spectrum.”

—Booklist

“Dr. Schutt’s voyage through the world of blood-feeders is alive with humor and the sheer fun of scientific exploration. He may become the literary heir to Stephen Jay Gould–if you can imagine Gould writing after downing twelve cups of coffee sweetened with nitrous oxide.”

—Charles Pellegrino

"What starts out as a horror movie of a book morphs into an entrancing exploration of the living world. Bill Schutt turns whatever fear and disgust you may feel towards nature's vampires into a healthy respect for evolution's power to fill every conceivable niche. And once you're done, you'll be spoiling one dinner party after another retelling Schutt's tales of bats, leeches, and bed bugs."

—Carl Zimmer, author of Parasite Rex and Microcosm: E. coli and the New Science of Life

“Having donated some of myself to most kinds of bloodsuckers during my field research around the world, mercifully with the exception of vampire bats and candiru catfish, I was totally absorbed by this thoroughly charming and scientifically accurate account.”

—Edward O. Wilson

“The combination of Bill Schutt's marvelous writing and Patricia J. Wynne's elegant illustrations makes Dark Banquet--the definitive account of blood feeding in nature-- an unstoppable, exhilarating read. Schutt brings both wisdom and wit to his coverage of fascinating facts about the biology of various creatures and the historical interplay of humans as victims, beneficiaries, and scientists. The book has the perfect balance of enlightenment, humor, an irreverence that is so true to a dedicated field biologist with a keen sense of subjects ranging from Leonardo Da Vinci's fascination with leech locomotion to New York's bed bug problem. Dark Banquet is engrossing without being gross at all!”

—Michael Novacek, Provost and Curator, American Museum of Natural History

From the Hardcover edition.

—The New York Times

“[P]rofiles some of the animal kingdom's dedicated bloodsuckers, from vampire bats and the dreaded candiru catfish to the not-so-dreaded vampire finch….Schutt is an engaging writer.”

—Washington Post Book World

"Zoologist Bill Schutt, through witty, informed writing, transforms bloodsuckers into enticing creatures."

—Metro (NY)

“With great scientific accuracy (backed up by extensive notes and a bibliography), text couched in layman’s terms, and a sense of breathless discovery, Schutt will make blood feeding just another choice on the culinary spectrum.”

—Booklist

“Dr. Schutt’s voyage through the world of blood-feeders is alive with humor and the sheer fun of scientific exploration. He may become the literary heir to Stephen Jay Gould–if you can imagine Gould writing after downing twelve cups of coffee sweetened with nitrous oxide.”

—Charles Pellegrino

"What starts out as a horror movie of a book morphs into an entrancing exploration of the living world. Bill Schutt turns whatever fear and disgust you may feel towards nature's vampires into a healthy respect for evolution's power to fill every conceivable niche. And once you're done, you'll be spoiling one dinner party after another retelling Schutt's tales of bats, leeches, and bed bugs."

—Carl Zimmer, author of Parasite Rex and Microcosm: E. coli and the New Science of Life

“Having donated some of myself to most kinds of bloodsuckers during my field research around the world, mercifully with the exception of vampire bats and candiru catfish, I was totally absorbed by this thoroughly charming and scientifically accurate account.”

—Edward O. Wilson

“The combination of Bill Schutt's marvelous writing and Patricia J. Wynne's elegant illustrations makes Dark Banquet--the definitive account of blood feeding in nature-- an unstoppable, exhilarating read. Schutt brings both wisdom and wit to his coverage of fascinating facts about the biology of various creatures and the historical interplay of humans as victims, beneficiaries, and scientists. The book has the perfect balance of enlightenment, humor, an irreverence that is so true to a dedicated field biologist with a keen sense of subjects ranging from Leonardo Da Vinci's fascination with leech locomotion to New York's bed bug problem. Dark Banquet is engrossing without being gross at all!”

—Michael Novacek, Provost and Curator, American Museum of Natural History

From the Hardcover edition.