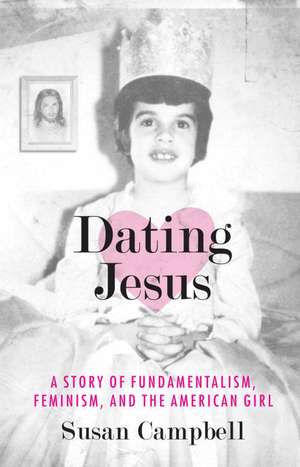

Dating Jesus: A Story of Fundamentalism, Feminism, and the American Girl

Autor Susan Campbellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2010

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Connecticut Book Awards (2010)

In this lovingly told tale, Susan Campbell takes us into the world of Christian fundamentalism—a world where details really, really matter. And she shows us what happened when she finally came to admit that in her faith, women would never be allowed a seat near the throne.

Preț: 146.31 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 219

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.00€ • 29.12$ • 23.12£

28.00€ • 29.12$ • 23.12£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807010723

ISBN-10: 0807010723

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 145 x 221 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807010723

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 145 x 221 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Recenzii

Simultaneously wisecracking and scholarly, both heartfelt and hilarious . . . I loved this book! —Wally Lamb, author of The Hour I First Believed

"This fond memoir of growing up a rebellious tomboy in a fundamentalist church that expects women to be pious, subservient and, above all, quiet tells what it feels like to have Jesus as your boyfriend-and what happens when you want to break up with him."—Ms.

"[A] heartfelt memoir . . . [Campbell's] writing is striking for the compassion with which she views her younger self, a fledgling believer confined in a cage of manmade rules."—Jane Ciabattari, More

"Rarely has a genuine feminist emerged from the modern evangelical movement. An exception is Susan Campbell."—Hanna Rosin, Mother Jones

"A mesmerizing, funny, impressionistic memoir of a spiritual and thoughtful person, one who has spent her life wrestling with religion, the meaning of faith and her feelings for the Divine."—Houston Chronicle

"Campbell has both a sense of humor and a knack for religious research . . . [and gives] readers a hook to grab on to as they ponder life's big questions alongside a tomboy theologian."—Harry Levins, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

"A moving account of closely cinched fundamentalist girlhood . . . Fundamentalism 'broke off in us,' like a sword, seems a poignant metaphor for the injuries suffered. Fortunately for the rest of us, [Campbell's] chosen salve for those wounds is the writing of astute and vivid prose."—Valerie Weaver-Zercher, The Christian Century

"This fond memoir of growing up a rebellious tomboy in a fundamentalist church that expects women to be pious, subservient and, above all, quiet tells what it feels like to have Jesus as your boyfriend-and what happens when you want to break up with him."—Ms.

"[A] heartfelt memoir . . . [Campbell's] writing is striking for the compassion with which she views her younger self, a fledgling believer confined in a cage of manmade rules."—Jane Ciabattari, More

"Rarely has a genuine feminist emerged from the modern evangelical movement. An exception is Susan Campbell."—Hanna Rosin, Mother Jones

"A mesmerizing, funny, impressionistic memoir of a spiritual and thoughtful person, one who has spent her life wrestling with religion, the meaning of faith and her feelings for the Divine."—Houston Chronicle

"Campbell has both a sense of humor and a knack for religious research . . . [and gives] readers a hook to grab on to as they ponder life's big questions alongside a tomboy theologian."—Harry Levins, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

"A moving account of closely cinched fundamentalist girlhood . . . Fundamentalism 'broke off in us,' like a sword, seems a poignant metaphor for the injuries suffered. Fortunately for the rest of us, [Campbell's] chosen salve for those wounds is the writing of astute and vivid prose."—Valerie Weaver-Zercher, The Christian Century

Extras

Chapter One: The Devil Is in an Air Bubble

The devil is in an air bubble floating beneath my baptismal robe.

This is troublesome, because I am trying to do the right

thing—and, incidentally, avoid hellfire. I have walked to the front

of my fundamentalist Christian church this Sunday morning to

profess my love for Jesus and be buried with him in the baptismal

grave. I will rise and walk anew, a new Christian, a good girl—

not sinless, but perfect nevertheless.

But this damn bubble is getting in the way. It is Satan, come

to thwart me.

I am a fundamentalist. I know that in order to spend eternity

in heaven with Jesus, I must be immersed completely

in the water, be it in a baptismal font, like this overly large

bathtub-type model at the front of my church, or in the swimming

pool at Green Valley Bible Camp, where I go every summer,

or in a river, or anywhere where the water will cover me completely.

I must be buried, figuratively speaking, because that is

how Jesus did it with his cousin, John the Baptizer, in the river

Jordan.1 It is how I want to do it now. I came to the earth sinless—

not like Catholic babies, who, I’d been told, drag Adam’s original

sin around like a tail. Not me. Had I died at birth, I would have

shot back to God in heaven like a rocket. But I did not die, and the

time I’ve been on earth since my birth I’ve spent accumulating

black blots on my soul, like cigarette burns in a gauze curtain.

And here Satan has floated up in a bubble beneath the thick

white robe, and so I am not, technically speaking, completely immersed.

My soul is encased in my body and my body is encased in

this gown, and a small portion of it has swollen to break the water’s

surface, like a tiny pregnancy, or the beginning of a thought.

My head is under. One hand is clenching my nose shut and the

other is crossed over my chest, half the posture of a corpse in a casket.

But if this dress doesn’t sink with the rest of me, the whole

ceremony will be useless.

I am a fundamentalist. We worry about such things.

A ceremonial joining-together only makes sense. I am thirteen

when I decide to make it official. I’d been flirting with Jesus since

age eight or so, the way a little girl will stand innocently next to

her cutest uncle, will preen and dance for attention with only a

dim idea of the greater weight of her actions. I meant no harm. I

just loved Jesus. He made me feel happy.

In my mind, Jesus had been flirting back, and why wouldn’t

he? Our families were close. I went to his house three times a week,

sat in his living room, listened to his stories, loudly sang songs to

him. Our relationship was inevitable, and it seemed the simplest

thing imaginable to declare my love.

And so on this bright and terrible Sunday morning I nervously slide out of my pew to walk up the aisle during the invitation

song, the tune we sing after the preacher gives his sermon. The invitation

song is a time of relief for those who think the preacher

has gone on too long, and a time of trepidation for the sinners

who are paying attention. Although the song varies depending

on who’s leading the singing, all the invitation songs share a tone

of exhortation firmly grounded in fear, meant to shake a few of

the ungodly loose from the trees. And I am a sinner. I know that

as assuredly as I know Jesus loves me. I am trying to live my life

to meet the impossible ideal of perfection set for me exactly 1,972

years earlier by my boyfriend. The Bible said Don’t lie, but I lie

several times a day. The Bible said Don’t steal, but I copied from

a friend one morning in social studies because I hadn’t taken the

time to do my own homework. The Bible said not to lust, and

while I am not clear what that means exactly, I harbor a deep and

abiding crush on a series of pop culture icons from Bobby Sherman

on—save for Donny Osmond, because he is too Mormon and

I don’t think I could convert him. But Donny is the only one from

Tiger Beat magazine for whom I have no tingling feelings. I know,

even though my church would frown on it because none of these

boy-men are members, that if any of them save Donny drove up

in a jacked-up Camaro and honked the horn, I would hop into the

front seat without a look back.

Oh I sinned, all right.

As I begin to walk to the front pew of the sanctuary at Fourth

and Forest church of Christ, I can hear the giggles and gasps from

my girlfriends left behind. Most of them have already taken the

walk to the front to declare their love for Jesus, but I have dragged

my feet. I know I need to be baptized—it would sure beat spending

eternity in hellfire—but it seems such an awesome step. I am

walking toward the highest church office I can reach as a female—

that of a baptized believer—and for that brief moment, all

eyes are on me. I will be a Christian. I will teach Sunday school

and participate in the odd rite of church dinners, where the mark

of distinction is given to any woman who can assemble an ordinary-

looking cake out of ingredients you wouldn’t expect, like

beer. Or potato chips. I will grow up and marry a deacon, the

worker bees of our church, who will one day grow old—like,

forty or so—and become an elder. I will raise up my children in

the way they should go, and when they are old, they will not depart

from me.2 I will wear red lipstick and aprons and gather my

grandchildren to my ample lap (all grandmas being fat). And finally,

I will recline in my rose-scented deathbed with a brave,

faint smile as my family gathers around me, and then I will rise

in spirit to my home in glory, leaving behind a blessed bunch

who look and sound and smell like me and who point to my faith

as their ideal. They will, of course, all be Christians, and they will

marry Christians and beget Christians, and not some watereddown

namby-pamby type, either, but fire-breathing and soulgrowing

Christians, members of the church of Christ, saved by

grace and fired with an obstinate belief in the black and white.

Give me that old-time religion! Yes, Lord!3

It is all laid out for me, both in the Bible and in the talks our

Sunday school teachers give us. I know my future as I know the

St. Louis Cardinals lineup from the tinny transistor I sneak into

my bed on game nights: Bob Gibson, Ted Simmons, Matty Alou,

Lou Brock, José Cruz, and the man who will ultimately betray

my faith in baseball and become a hated Yankee, Joe Torre. Those

Cardinals will win the pennant one day, but I will be a Christian

today.

The sanctuary in which I walk is a high-ceilinged, cavernous

room covered completely—walls and ceiling—in knotty pine that

holds my secret sin. When I am bored—and during three-hour

Sunday-morning services I am often bored—I attempt to count

the knots in the panels behind the preacher. I lose count and start

again, lose count and start again. I feel guilty about that, but I

am sitting through three sermons a week and once I recognize the

preacher’s theme (sin, mercy, salvation), I start counting knots.

The room seats roughly seven hundred souls. I say roughly,

because we never fill it. It was built amid much discussion and

hard feelings at a time when my church was among the fastestgrowing

Christian groups in the country. Of course we would fill

it, we told one another, even if our regular Sunday-morning attendance

hovered around three hundred or so. God would provide.

We just needed to have the right amount of pews. The

interior looks as we imagine the ark of Noah would look—spare,

with not one cross on display. Jesus hung on a real cross. Who

were we to use the emblem of his shame as decor? And why

would we, as girls, wear small golden crosses when the real one

was so much bigger and uglier?4 The pews are padded—another

discussion—and there are no prayer benches, for fear that they

would put us in company with the Catholics. Still, I never once

saw someone drop to his or her knees during public prayer. We

are, one visiting minister derided us, the only group of believers

that sits to sing and stands to pray.

In fact, the building was built on prayer—and a painful

schism. When you believe you are holy and have God on your side,

you easily cross over into being dogmatic. We split over paving

the parking lot. The anti-paving bunch argued that Jesus never

walked on pavement, and that we shouldn’t be so fine-haired as to

worry about muddying our good shoes as we scrambled to our

(padded) pews. And besides, the money could be used for a

greater purpose—namely, saving souls. The grandparents of this

crowd had cheered at the outcome of the Scopes Monkey Trial.

Consider them opponents of creeping and sweeping modernity.

The other bunch—and, oddly, my notoriously hidebound

family sided with them—said that paving a parking lot was right

and good, that it didn’t hurt to have a few creature comforts, and

the anti-paving crowd hadn’t kicked up a fuss over the fancy

new air-conditioning, now, had they? When the church splits, we

stay with the paved group. And when it splits another time over

whether the grape juice of the Lord’s Supper (the communion we

enjoyed every Sunday) should come from one cup, as Jesus may

have shared it, or from tiny shot glasses set into special circular

trays made for such an event, my family again sides with the progressives.

The others we derisively call “one-cuppers,” as damning

a phrase as “dumb-ass hillbilly.”

It would be my family’s one concession to change.

Among the literal-minded, schisms are just waiting to surface,

ready to crack open at any moment. Elsewhere, the other

churches of my faith—we had no central hierarchy, opting instead

for home rule by a group of older men, the elders—would

split and split again, over adding a pastoral counseling service,

or a daycare center—more modernity, in other words, but that

was later. For now, we felt the sheep were scattered, and when we

brought them home, they could clatter across pavement to sit in

padded pews and partake in the liquid part of the Lord’s Supper

from tiny shot glasses meant for just such a purpose—and likely

to form a barrier against the common cold as well.

The devil is in an air bubble floating beneath my baptismal robe.

This is troublesome, because I am trying to do the right

thing—and, incidentally, avoid hellfire. I have walked to the front

of my fundamentalist Christian church this Sunday morning to

profess my love for Jesus and be buried with him in the baptismal

grave. I will rise and walk anew, a new Christian, a good girl—

not sinless, but perfect nevertheless.

But this damn bubble is getting in the way. It is Satan, come

to thwart me.

I am a fundamentalist. I know that in order to spend eternity

in heaven with Jesus, I must be immersed completely

in the water, be it in a baptismal font, like this overly large

bathtub-type model at the front of my church, or in the swimming

pool at Green Valley Bible Camp, where I go every summer,

or in a river, or anywhere where the water will cover me completely.

I must be buried, figuratively speaking, because that is

how Jesus did it with his cousin, John the Baptizer, in the river

Jordan.1 It is how I want to do it now. I came to the earth sinless—

not like Catholic babies, who, I’d been told, drag Adam’s original

sin around like a tail. Not me. Had I died at birth, I would have

shot back to God in heaven like a rocket. But I did not die, and the

time I’ve been on earth since my birth I’ve spent accumulating

black blots on my soul, like cigarette burns in a gauze curtain.

And here Satan has floated up in a bubble beneath the thick

white robe, and so I am not, technically speaking, completely immersed.

My soul is encased in my body and my body is encased in

this gown, and a small portion of it has swollen to break the water’s

surface, like a tiny pregnancy, or the beginning of a thought.

My head is under. One hand is clenching my nose shut and the

other is crossed over my chest, half the posture of a corpse in a casket.

But if this dress doesn’t sink with the rest of me, the whole

ceremony will be useless.

I am a fundamentalist. We worry about such things.

A ceremonial joining-together only makes sense. I am thirteen

when I decide to make it official. I’d been flirting with Jesus since

age eight or so, the way a little girl will stand innocently next to

her cutest uncle, will preen and dance for attention with only a

dim idea of the greater weight of her actions. I meant no harm. I

just loved Jesus. He made me feel happy.

In my mind, Jesus had been flirting back, and why wouldn’t

he? Our families were close. I went to his house three times a week,

sat in his living room, listened to his stories, loudly sang songs to

him. Our relationship was inevitable, and it seemed the simplest

thing imaginable to declare my love.

And so on this bright and terrible Sunday morning I nervously slide out of my pew to walk up the aisle during the invitation

song, the tune we sing after the preacher gives his sermon. The invitation

song is a time of relief for those who think the preacher

has gone on too long, and a time of trepidation for the sinners

who are paying attention. Although the song varies depending

on who’s leading the singing, all the invitation songs share a tone

of exhortation firmly grounded in fear, meant to shake a few of

the ungodly loose from the trees. And I am a sinner. I know that

as assuredly as I know Jesus loves me. I am trying to live my life

to meet the impossible ideal of perfection set for me exactly 1,972

years earlier by my boyfriend. The Bible said Don’t lie, but I lie

several times a day. The Bible said Don’t steal, but I copied from

a friend one morning in social studies because I hadn’t taken the

time to do my own homework. The Bible said not to lust, and

while I am not clear what that means exactly, I harbor a deep and

abiding crush on a series of pop culture icons from Bobby Sherman

on—save for Donny Osmond, because he is too Mormon and

I don’t think I could convert him. But Donny is the only one from

Tiger Beat magazine for whom I have no tingling feelings. I know,

even though my church would frown on it because none of these

boy-men are members, that if any of them save Donny drove up

in a jacked-up Camaro and honked the horn, I would hop into the

front seat without a look back.

Oh I sinned, all right.

As I begin to walk to the front pew of the sanctuary at Fourth

and Forest church of Christ, I can hear the giggles and gasps from

my girlfriends left behind. Most of them have already taken the

walk to the front to declare their love for Jesus, but I have dragged

my feet. I know I need to be baptized—it would sure beat spending

eternity in hellfire—but it seems such an awesome step. I am

walking toward the highest church office I can reach as a female—

that of a baptized believer—and for that brief moment, all

eyes are on me. I will be a Christian. I will teach Sunday school

and participate in the odd rite of church dinners, where the mark

of distinction is given to any woman who can assemble an ordinary-

looking cake out of ingredients you wouldn’t expect, like

beer. Or potato chips. I will grow up and marry a deacon, the

worker bees of our church, who will one day grow old—like,

forty or so—and become an elder. I will raise up my children in

the way they should go, and when they are old, they will not depart

from me.2 I will wear red lipstick and aprons and gather my

grandchildren to my ample lap (all grandmas being fat). And finally,

I will recline in my rose-scented deathbed with a brave,

faint smile as my family gathers around me, and then I will rise

in spirit to my home in glory, leaving behind a blessed bunch

who look and sound and smell like me and who point to my faith

as their ideal. They will, of course, all be Christians, and they will

marry Christians and beget Christians, and not some watereddown

namby-pamby type, either, but fire-breathing and soulgrowing

Christians, members of the church of Christ, saved by

grace and fired with an obstinate belief in the black and white.

Give me that old-time religion! Yes, Lord!3

It is all laid out for me, both in the Bible and in the talks our

Sunday school teachers give us. I know my future as I know the

St. Louis Cardinals lineup from the tinny transistor I sneak into

my bed on game nights: Bob Gibson, Ted Simmons, Matty Alou,

Lou Brock, José Cruz, and the man who will ultimately betray

my faith in baseball and become a hated Yankee, Joe Torre. Those

Cardinals will win the pennant one day, but I will be a Christian

today.

The sanctuary in which I walk is a high-ceilinged, cavernous

room covered completely—walls and ceiling—in knotty pine that

holds my secret sin. When I am bored—and during three-hour

Sunday-morning services I am often bored—I attempt to count

the knots in the panels behind the preacher. I lose count and start

again, lose count and start again. I feel guilty about that, but I

am sitting through three sermons a week and once I recognize the

preacher’s theme (sin, mercy, salvation), I start counting knots.

The room seats roughly seven hundred souls. I say roughly,

because we never fill it. It was built amid much discussion and

hard feelings at a time when my church was among the fastestgrowing

Christian groups in the country. Of course we would fill

it, we told one another, even if our regular Sunday-morning attendance

hovered around three hundred or so. God would provide.

We just needed to have the right amount of pews. The

interior looks as we imagine the ark of Noah would look—spare,

with not one cross on display. Jesus hung on a real cross. Who

were we to use the emblem of his shame as decor? And why

would we, as girls, wear small golden crosses when the real one

was so much bigger and uglier?4 The pews are padded—another

discussion—and there are no prayer benches, for fear that they

would put us in company with the Catholics. Still, I never once

saw someone drop to his or her knees during public prayer. We

are, one visiting minister derided us, the only group of believers

that sits to sing and stands to pray.

In fact, the building was built on prayer—and a painful

schism. When you believe you are holy and have God on your side,

you easily cross over into being dogmatic. We split over paving

the parking lot. The anti-paving bunch argued that Jesus never

walked on pavement, and that we shouldn’t be so fine-haired as to

worry about muddying our good shoes as we scrambled to our

(padded) pews. And besides, the money could be used for a

greater purpose—namely, saving souls. The grandparents of this

crowd had cheered at the outcome of the Scopes Monkey Trial.

Consider them opponents of creeping and sweeping modernity.

The other bunch—and, oddly, my notoriously hidebound

family sided with them—said that paving a parking lot was right

and good, that it didn’t hurt to have a few creature comforts, and

the anti-paving crowd hadn’t kicked up a fuss over the fancy

new air-conditioning, now, had they? When the church splits, we

stay with the paved group. And when it splits another time over

whether the grape juice of the Lord’s Supper (the communion we

enjoyed every Sunday) should come from one cup, as Jesus may

have shared it, or from tiny shot glasses set into special circular

trays made for such an event, my family again sides with the progressives.

The others we derisively call “one-cuppers,” as damning

a phrase as “dumb-ass hillbilly.”

It would be my family’s one concession to change.

Among the literal-minded, schisms are just waiting to surface,

ready to crack open at any moment. Elsewhere, the other

churches of my faith—we had no central hierarchy, opting instead

for home rule by a group of older men, the elders—would

split and split again, over adding a pastoral counseling service,

or a daycare center—more modernity, in other words, but that

was later. For now, we felt the sheep were scattered, and when we

brought them home, they could clatter across pavement to sit in

padded pews and partake in the liquid part of the Lord’s Supper

from tiny shot glasses meant for just such a purpose—and likely

to form a barrier against the common cold as well.

Cuprins

One

The Devil’s in an Air Bubble

Two

I Don’t Want to Preach, But . . .

Three

Knocking Doors for Jesus

Four

A Good Christian Woman

Five

The Theology of Softball

Six

A Woman’s Role

Seven

A Scary God

Eight

The Reluctant Female

Nine

Still, Small Voice

Ten

Water Jugs

Eleven

Jesus Haunts Me, This I Know

Acknowledgments 207

About My Sources 208

The Devil’s in an Air Bubble

Two

I Don’t Want to Preach, But . . .

Three

Knocking Doors for Jesus

Four

A Good Christian Woman

Five

The Theology of Softball

Six

A Woman’s Role

Seven

A Scary God

Eight

The Reluctant Female

Nine

Still, Small Voice

Ten

Water Jugs

Eleven

Jesus Haunts Me, This I Know

Acknowledgments 207

About My Sources 208

Premii

- Connecticut Book Awards Winner, 2010