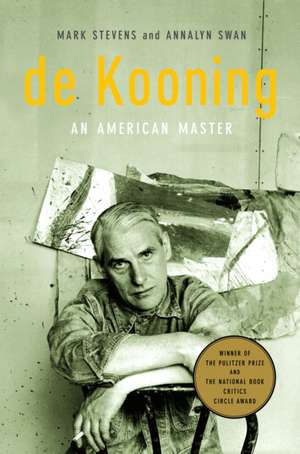

de Kooning: An American Master

Autor Annalyn Swan, Mark Stevensen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

The first major biography of de Kooning captures both the life and work of this complex, romantic figure in American culture. Ten years in the making, and based on previously unseen letters and documents as well as on hundreds of interviews, this is a fresh, richly detailed, and masterful portrait. The young de Kooning overcame an unstable, impoverished, and often violent early family life to enter the Academie in Rotterdam, where he learned both classic art and guild techniques. Arriving in New York as a stowaway from Holland in 1926, he underwent a long struggle to become a painter and an American, developing a passionate friendship with his fellow immigrant Arshile Gorky, who was both a mentor and an inspiration. During the Depression, de Kooning emerged as a central figure in the bohemian world of downtown New York, surviving by doing commercial work and painting murals for the WPA. His first show at the Egan Gallery in 1948 was a revelation. Soon, the critics Harold Rosenberg and Thomas Hess were championing his work, and de Kooning took his place as the charismatic leader of the New York school—just as American art began to dominate the international scene.

Dashingly handsome and treated like a movie star on the streets of downtown New York, de Kooning had a tumultuous marriage to Elaine de Kooning, herself a fascinating character of the period. At the height of his fame, he spent his days painting powerful abstractions and intense, disturbing pictures of the female figure—and his nights living on the edge, drinking, womanizing, and talking at the Cedar bar with such friends as Franz Kline and Frank O’Hara. By the 1960s, exhausted by the feverish art world, he retreated to the Springs on Long Island, where he painted an extraordinary series of lush pastorals. In the 1980s, as he slowly declined into what was almost certainly Alzheimer’s, he created a vast body of haunting and ethereal late work.

This is an authoritative and brilliant exploration of the art, life, and world of an American master.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 207.39 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 311

Preț estimativ în valută:

39.68€ • 41.43$ • 32.84£

39.68€ • 41.43$ • 32.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 53.59 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375711169

ISBN-10: 0375711163

Pagini: 732

Ilustrații: 16 PP 4-C; 68 PHOTOGRAPHS/TEXT

Dimensiuni: 160 x 231 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.99 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

ISBN-10: 0375711163

Pagini: 732

Ilustrații: 16 PP 4-C; 68 PHOTOGRAPHS/TEXT

Dimensiuni: 160 x 231 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.99 kg

Editura: ALFRED A KNOPF

Notă biografică

Mark Stevens is the art critic for New York magazine. He has also been the art critic for The New Republic and Newsweek and has written for such publications as Vanity Fair, the New York Times, and The New Yorker. He lives in New York City.

Annalyn Swan has been a writer at Time and an award-winning music critic and senior arts editor at Newsweek. She has written for The New Republic, The Atlantic Monthly, and New York magazine. She lives in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

Annalyn Swan has been a writer at Time and an award-winning music critic and senior arts editor at Newsweek. She has written for The New Republic, The Atlantic Monthly, and New York magazine. She lives in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

My mother was a tyrant and Willem was stubborn. —Marie van Meurs–de Kooning, de Kooning’s sister

In Rotterdam, the boys often gathered near the harbor, playing games and picking up pocket money running errands for the dockworkers. They trailed behind the gangs of foreign sailors and watched the eccentrics who loitered around the docks. The Schiedamsedijk district—filled with bars, dance halls, street musicians, and prostitutes—was nearby. So were the shops of the Jewish Quarter, which kept unconventional hours and possessed the allure of another culture. Around the docks there was always some excitement. Rules of every kind were being broken—or so a boy could hope.

Willem de Kooning was one of the boys who haunted the waterfront. Among the largest and most modern in the world, the harbor was Rotterdam’s heart, a pulsing, vital, rude area that in the good years of the early twentieth century worked around the clock. It was a place of both mystery and hard labor, of constant traffic between the practical and the exotic. Cranes broke the line of the horizon. Ships arrived from faraway places. Strange words hung in the air. Here, de Kooning began to develop a taste for the flux and hurly-burly of the modern world. Change, modernity, and the sea came together in his mind.

Even more important, the harbor was an open promise. If de Kooning relished the human energy of the docks, his imagination also required the sea, his first and most constant muse, just beyond. “There is something about being in touch with the sea that makes me feel good,” he would later tell the critic Harold Rosenberg. “That’s where most of my paintings come from, even when I made them in New York.” The child whom his mother and sister called “Wim” would watch the ships by the hour. He liked the way “the air mirrored the water” and enjoyed the rippling give-and-take of color and light between the sky above and the sea below. When he was only four, according to his older sister, Marie, he surprised his family by drawing a big toom (his word for “boat”) on the wallpaper, the first “de Kooning” on record. Early on, the sea also became synonymous with freedom—from poverty and a too-tidy, often smothering country that, like many Protestant cultures, made a point of individuality while encouraging conformity. And freedom, too, from a suffocating family torn by furious arguments and harsh beatings.

De Kooning means “the king” in Dutch. There was nothing royal, however, about de Kooning’s background. He was born on April 24, 1904, on the ground floor of a house that still stands at Zaagmolenstraat 13, a thoroughfare in the working-class district of Rotterdam Noord (North Rotterdam). The city of his birth was a place of tension and impermanence, at once modern and premodern. In the Rotterdam of de Kooning’s youth, workers bought produce from peasants who came to the market wearing traditional costume and wooden shoes. It was a city in which tradition was constantly challenged by the new.

Until 1850, Rotterdam was a quiet provincial port twenty-three miles upriver from the North Sea. In the second half of the nineteenth century, however, it became the Dutch city that welcomed the future, a place of gritty and dynamic vitality. It was the first Dutch city to have electricity. It was also the least snobbish city in Holland. In contrast to the aristocratic The Hague, the historic royal capital, Rotterdam was more than willing to tear down the past in order to adapt to the demands of industry. In the 1860s, Rotterdam boldly filled in the river after which it was named, the Rotte, because it was too small to handle modern shipping. It used the space to run a railway to the water. In 1874, the city constructed modern shipping facilities. The rapidly developing German industries of the Rhineland, in need of a port, then sent their goods down the Rhine to Rotterdam. In 1890 the Nieuw Waterweg—the New Waterway, or Rotterdam Seaway—connected Rotterdam directly to open water; before that, ships had to traverse a series of difficult channels. The city became an economic power. The harbor defined the city’s character, regulated its rhythms, and its unending activity turned night into day; the flow of traffic determined how well, or how poorly, Rotterdammers would eat.

At midcentury, the city had a population of fifty thousand. During the next twenty-five years, the number of inhabitants tripled. By the turn of the century, around the time de Kooning was born, Rotterdam’s population was over 300,000, and the city was the fastest growing in Holland. North Rotterdam, where de Kooning mostly grew up, was developed by speculators to house the rapidly expanding working-class population. A shabby, cramped district of endless-seeming rowhouses, North Rotterdam lay just north and east of the city center. Like other poor districts of the city, including huge areas of working-class housing south of central Rotterdam, it was home to an itinerant population of sailors, stevedores, and peasants. Many such peasants, driven from the land by cheap grain imported from North America, clumped together in colonies within the city. Thousands of poor immigrants making their way to America from Germany and eastern Europe poured into the city by train, before booking passage on the Holland-America line.

Despite the ceaseless change, Rotterdam remained fairly stable. A small number of shipbuilders and wealthy families—many of them original Rotterdammers—dominated the city. Laborers, economically insecure and often desperate for work, were reluctant to risk their jobs by challenging authority. Although the Dutch have often prided themselves on being less class conscious than the English or the French, the Holland of de Kooning’s youth, like the industrializing Midlands of England or the Wales of the young D. H. Lawrence, was a stratified society in which advancement was difficult and the wounds of class sharp. De Kooning’s ancestors were mostly servants, laborers, and craftsmen. His paternal great-grandfather, Cornelis de Kooning, was a shipbuilder from Woerden, a small river town about twenty-five miles northwest of Rotterdam. Born in 1810 or 1811, Cornelis moved from Woerden to Delfshaven, a coastal town west of Rotterdam where his son Willem—named after Cornelis’s father—was born in 1838. Sometime in the 1840s, Cornelis moved to Rotterdam to work in the city’s burgeoning shipbuilding business. He settled at Vinstraat 2 with his wife, Anna Catharina Jacoba Jurgens, his son Willem, and his daughter Jacoba.

In 1850, Cornelis died at the age of thirty-nine or forty, leaving his wife and children on their own. For the next ten years, his wife supported her family by working as a maid. At the time of her husband’s death, Willem—the grandfather after whom de Kooning would be named—was twelve years old and still in school. His education ended soon afterward. (It was the custom until well after the turn of the century for working-class children to leave school at twelve, then be apprenticed in various crafts.) Like his father, Willem worked in the shipyards. In 1865 he married Maria van Ladenstijn, who had been a maid. They had ten children, four of them boys. Among them was de Kooning’s father, Leendert.

Leendert was born in Rotterdam on February 10, 1876, and grew into an ambitious but also stiff and emotionally withdrawn man. His face was shuttered—a vein of selfishness, according to family lore, ran through the de Koonings. He began his working life selling flowers, first from a cart and then at a flower stand at the railroad station. In 1896, the year he turned twenty, he started a small company with his oldest brother that bottled and distributed beer to pubs. Eventually he went off on his own, establishing a beer-bottling and distribution business in a modest building at Vledhoekstraat 26 in North Rotterdam, not far from a large new Heineken brewery. He appeared stable and was earning a little money. If he was very reserved, that was hardly unusual in Holland, and might have even appeared romantic in a handsome man in his early twenties. In 1897 or 1898, his eye settled upon Cornelia Nobel, who was everything Leendert was not—fiery, impetuous, caustic, and outspoken. In turn-of-the-century Rotterdam, Leendert’s ambitious and frugal nature would make him seem an excellent match for a working-class girl like Cornelia Nobel.

Cornelia’s family had lived in Schiedam, a town adjacent to western Rotterdam, since at least the eighteenth century. In 1873, Cornelia’s mother—also named Cornelia—had married Christiaan Gerardus Nobel, a packing-case maker and carpenter. The couple settled at Rotterdamsedijk 47A, in a small lane in Schiedam, where Nobel made barrels and cases to hold the cheap gin for which Schiedam was known. The marriage produced nine children, five of whom died young. Three of the surviving children were girls. (The lone son, de Kooning’s uncle, Chris Nobel, was the first in the family to set out for America. He settled in Brooklyn, where de Kooning sometimes visited him after coming to New York.) Cornelia was born on March 3, 1877. Even as a child she was considered formidable. She possessed, as her relatives said diplomatically, a “temperament.”

Small and slim, Cornelia had black hair, dark eyes, and a figure in which she took great pride. She was a restless young woman, constantly on edge, with a sharp temper and wicked tongue. She rarely laughed. Acquaintances consistently thought of her as being much taller and bigger than she was, a “masterful woman who dominated the entire family,” in the words of Jacobus “Koos” Lassooy, her third surviving child and the offspring of a later second marriage. Everyone in her family found her difficult. Henk Hofman, a cousin of de Kooning’s, said that even his mother—Cornelia’s sister—could not bear her for long. A woman who demanded center stage throughout her life, Cornelia was histrionic by nature; an interest in performing seems to have run in her family. She sang in her youth, according to family history, and did some amateur acting once her children were grown. Her relatives credited her with taste—which may have been a way of saying she was socially ambitious and put on airs. She was also “very quick,” according to members of her family, and spoke rapid-fire Dutch with “a heavy” Rotterdam accent.

As an adolescent, Cornelia left her family in August 1894 and went to the town of Haarlem, probably to work as a maid. It was a bold step: Haarlem was about fifty miles from Rotterdam, a significant distance in that era. But Cornelia returned to Schiedam the following year, at the end of October 1895, perhaps because she was ill-suited to the role of a servant. Two possibilities were open to a woman in her position. She could marry, or she could work in menial jobs. She was a pretty young woman, and her flair and dramatic personality no doubt proved a charming and interesting challenge to young men. In September 1898, she became pregnant with Leendert’s child. Such an occurrence was not unusual, either for the period or the couple’s social class. If pregnancy out of wedlock was not condoned, neither was it forcefully condemned. Few young men could afford to support a family; members of the Dutch working class often married late. As a result, it was not surprising that the young engaged in sex outside of marriage or that, in the days before birth control, young women often became pregnant. Rotterdam was a city full of people at loose ends in which traditional sexual mores were more respected than followed.

Nonetheless, a man was still expected to take responsibility for a woman he impregnated. The couple was married on December 22, 1898, in Schiedam. Leendert was twenty-two, Cornelia twenty-one. No one knows whether their marriage was strongly desired or merely the result of a brief sexual encounter. What is certain, however, is that the young couple immediately came under intense personal pressure. In 1899, six months after the wedding, de Kooning’s older sister, Marie, was born. Twin girls—Adriana and Cornelia—soon followed, in 1901, but they died days after their birth. Then came another daughter, Cornelia, in 1902, who died when she was eight months old. Willem de Kooning—the fifth child, but only the second to survive—was born in 1904, on April 24. By then, Cornelia had spent virtually all of her married life pregnant, either taking care of infants or burying them. She did so in a neighborhood where every day was a struggle: de Kooning’s family was part of a great mass of people hanging on week by week, trying to find their way in a newly evolving society.

Her husband had little energy to give to his family. Still in his twenties, he was working hard to establish his own business, hiring several employees to help him bottle beer for Heineken and other breweries. He also delivered the beer by means of dog and pony carts from his Vledhoekstraat concern to pubs throughout the district. Soon he expanded his business to bottle and distribute Elko lemonade as well. At the time of Willem’s birth, the de Koonings lived on Zaagmolenstraat, where the houses were slightly larger than those on the neighboring side streets—a subtle mark of Leendert’s rise in the world. But the house itself was anything but fancy. In de Kooning’s neighborhood, a man was rich if he owned a bicycle. (It was not unusual in the Rotterdam of 1910 for a man to walk two hours each way to work.) Most money was spent on necessities, though workers often blew their paychecks in the pubs—the only spots of warmth and brightness in the dank darkness of a Rotterdam winter, when the wind swept in from the North Sea. Meat was usually eaten once a week, on Sundays. The staple was potatoes flavored with lard from the butcher’s shop.

Housing for workers, including the house where the de Koonings lived, was typically built according to the same plan. An apartment consisted of two small rooms, one used as a parlor and the other as a kitchen and gathering spot for the family. In between the two rooms was an even smaller and windowless half-room—essentially a passageway—which served as a communal bedroom. On each side of the passageway there was a sleeping alcove, one for the parents and the other for the children; as many as three or four children might share a bed. Water came from a cold-water tap on the landing that was used by the two families sharing the floor. They also used a common toilet, located in a closet on the landing, which contained a bucket that was emptied manually. Since heat cost money, people were often cold. The de Koonings probably used a coal stove. Those still poorer relied on small cooking stoves to take the chill off the day; coins were inserted into a meter that turned on the gas. Baths were typically taken once a week at most, either at a public bath or at home, where each member of the family used the same tub of heated water. The hot water was purchased at the local grocery store and then hauled back home and up the steps to the apartment. Since washing clothes was difficult and expensive—it required buying hot water or hiring a laundress—clothes were rarely clean. Bedclothes, cumbersome and hard to dry, were almost never washed.

In Rotterdam, the boys often gathered near the harbor, playing games and picking up pocket money running errands for the dockworkers. They trailed behind the gangs of foreign sailors and watched the eccentrics who loitered around the docks. The Schiedamsedijk district—filled with bars, dance halls, street musicians, and prostitutes—was nearby. So were the shops of the Jewish Quarter, which kept unconventional hours and possessed the allure of another culture. Around the docks there was always some excitement. Rules of every kind were being broken—or so a boy could hope.

Willem de Kooning was one of the boys who haunted the waterfront. Among the largest and most modern in the world, the harbor was Rotterdam’s heart, a pulsing, vital, rude area that in the good years of the early twentieth century worked around the clock. It was a place of both mystery and hard labor, of constant traffic between the practical and the exotic. Cranes broke the line of the horizon. Ships arrived from faraway places. Strange words hung in the air. Here, de Kooning began to develop a taste for the flux and hurly-burly of the modern world. Change, modernity, and the sea came together in his mind.

Even more important, the harbor was an open promise. If de Kooning relished the human energy of the docks, his imagination also required the sea, his first and most constant muse, just beyond. “There is something about being in touch with the sea that makes me feel good,” he would later tell the critic Harold Rosenberg. “That’s where most of my paintings come from, even when I made them in New York.” The child whom his mother and sister called “Wim” would watch the ships by the hour. He liked the way “the air mirrored the water” and enjoyed the rippling give-and-take of color and light between the sky above and the sea below. When he was only four, according to his older sister, Marie, he surprised his family by drawing a big toom (his word for “boat”) on the wallpaper, the first “de Kooning” on record. Early on, the sea also became synonymous with freedom—from poverty and a too-tidy, often smothering country that, like many Protestant cultures, made a point of individuality while encouraging conformity. And freedom, too, from a suffocating family torn by furious arguments and harsh beatings.

De Kooning means “the king” in Dutch. There was nothing royal, however, about de Kooning’s background. He was born on April 24, 1904, on the ground floor of a house that still stands at Zaagmolenstraat 13, a thoroughfare in the working-class district of Rotterdam Noord (North Rotterdam). The city of his birth was a place of tension and impermanence, at once modern and premodern. In the Rotterdam of de Kooning’s youth, workers bought produce from peasants who came to the market wearing traditional costume and wooden shoes. It was a city in which tradition was constantly challenged by the new.

Until 1850, Rotterdam was a quiet provincial port twenty-three miles upriver from the North Sea. In the second half of the nineteenth century, however, it became the Dutch city that welcomed the future, a place of gritty and dynamic vitality. It was the first Dutch city to have electricity. It was also the least snobbish city in Holland. In contrast to the aristocratic The Hague, the historic royal capital, Rotterdam was more than willing to tear down the past in order to adapt to the demands of industry. In the 1860s, Rotterdam boldly filled in the river after which it was named, the Rotte, because it was too small to handle modern shipping. It used the space to run a railway to the water. In 1874, the city constructed modern shipping facilities. The rapidly developing German industries of the Rhineland, in need of a port, then sent their goods down the Rhine to Rotterdam. In 1890 the Nieuw Waterweg—the New Waterway, or Rotterdam Seaway—connected Rotterdam directly to open water; before that, ships had to traverse a series of difficult channels. The city became an economic power. The harbor defined the city’s character, regulated its rhythms, and its unending activity turned night into day; the flow of traffic determined how well, or how poorly, Rotterdammers would eat.

At midcentury, the city had a population of fifty thousand. During the next twenty-five years, the number of inhabitants tripled. By the turn of the century, around the time de Kooning was born, Rotterdam’s population was over 300,000, and the city was the fastest growing in Holland. North Rotterdam, where de Kooning mostly grew up, was developed by speculators to house the rapidly expanding working-class population. A shabby, cramped district of endless-seeming rowhouses, North Rotterdam lay just north and east of the city center. Like other poor districts of the city, including huge areas of working-class housing south of central Rotterdam, it was home to an itinerant population of sailors, stevedores, and peasants. Many such peasants, driven from the land by cheap grain imported from North America, clumped together in colonies within the city. Thousands of poor immigrants making their way to America from Germany and eastern Europe poured into the city by train, before booking passage on the Holland-America line.

Despite the ceaseless change, Rotterdam remained fairly stable. A small number of shipbuilders and wealthy families—many of them original Rotterdammers—dominated the city. Laborers, economically insecure and often desperate for work, were reluctant to risk their jobs by challenging authority. Although the Dutch have often prided themselves on being less class conscious than the English or the French, the Holland of de Kooning’s youth, like the industrializing Midlands of England or the Wales of the young D. H. Lawrence, was a stratified society in which advancement was difficult and the wounds of class sharp. De Kooning’s ancestors were mostly servants, laborers, and craftsmen. His paternal great-grandfather, Cornelis de Kooning, was a shipbuilder from Woerden, a small river town about twenty-five miles northwest of Rotterdam. Born in 1810 or 1811, Cornelis moved from Woerden to Delfshaven, a coastal town west of Rotterdam where his son Willem—named after Cornelis’s father—was born in 1838. Sometime in the 1840s, Cornelis moved to Rotterdam to work in the city’s burgeoning shipbuilding business. He settled at Vinstraat 2 with his wife, Anna Catharina Jacoba Jurgens, his son Willem, and his daughter Jacoba.

In 1850, Cornelis died at the age of thirty-nine or forty, leaving his wife and children on their own. For the next ten years, his wife supported her family by working as a maid. At the time of her husband’s death, Willem—the grandfather after whom de Kooning would be named—was twelve years old and still in school. His education ended soon afterward. (It was the custom until well after the turn of the century for working-class children to leave school at twelve, then be apprenticed in various crafts.) Like his father, Willem worked in the shipyards. In 1865 he married Maria van Ladenstijn, who had been a maid. They had ten children, four of them boys. Among them was de Kooning’s father, Leendert.

Leendert was born in Rotterdam on February 10, 1876, and grew into an ambitious but also stiff and emotionally withdrawn man. His face was shuttered—a vein of selfishness, according to family lore, ran through the de Koonings. He began his working life selling flowers, first from a cart and then at a flower stand at the railroad station. In 1896, the year he turned twenty, he started a small company with his oldest brother that bottled and distributed beer to pubs. Eventually he went off on his own, establishing a beer-bottling and distribution business in a modest building at Vledhoekstraat 26 in North Rotterdam, not far from a large new Heineken brewery. He appeared stable and was earning a little money. If he was very reserved, that was hardly unusual in Holland, and might have even appeared romantic in a handsome man in his early twenties. In 1897 or 1898, his eye settled upon Cornelia Nobel, who was everything Leendert was not—fiery, impetuous, caustic, and outspoken. In turn-of-the-century Rotterdam, Leendert’s ambitious and frugal nature would make him seem an excellent match for a working-class girl like Cornelia Nobel.

Cornelia’s family had lived in Schiedam, a town adjacent to western Rotterdam, since at least the eighteenth century. In 1873, Cornelia’s mother—also named Cornelia—had married Christiaan Gerardus Nobel, a packing-case maker and carpenter. The couple settled at Rotterdamsedijk 47A, in a small lane in Schiedam, where Nobel made barrels and cases to hold the cheap gin for which Schiedam was known. The marriage produced nine children, five of whom died young. Three of the surviving children were girls. (The lone son, de Kooning’s uncle, Chris Nobel, was the first in the family to set out for America. He settled in Brooklyn, where de Kooning sometimes visited him after coming to New York.) Cornelia was born on March 3, 1877. Even as a child she was considered formidable. She possessed, as her relatives said diplomatically, a “temperament.”

Small and slim, Cornelia had black hair, dark eyes, and a figure in which she took great pride. She was a restless young woman, constantly on edge, with a sharp temper and wicked tongue. She rarely laughed. Acquaintances consistently thought of her as being much taller and bigger than she was, a “masterful woman who dominated the entire family,” in the words of Jacobus “Koos” Lassooy, her third surviving child and the offspring of a later second marriage. Everyone in her family found her difficult. Henk Hofman, a cousin of de Kooning’s, said that even his mother—Cornelia’s sister—could not bear her for long. A woman who demanded center stage throughout her life, Cornelia was histrionic by nature; an interest in performing seems to have run in her family. She sang in her youth, according to family history, and did some amateur acting once her children were grown. Her relatives credited her with taste—which may have been a way of saying she was socially ambitious and put on airs. She was also “very quick,” according to members of her family, and spoke rapid-fire Dutch with “a heavy” Rotterdam accent.

As an adolescent, Cornelia left her family in August 1894 and went to the town of Haarlem, probably to work as a maid. It was a bold step: Haarlem was about fifty miles from Rotterdam, a significant distance in that era. But Cornelia returned to Schiedam the following year, at the end of October 1895, perhaps because she was ill-suited to the role of a servant. Two possibilities were open to a woman in her position. She could marry, or she could work in menial jobs. She was a pretty young woman, and her flair and dramatic personality no doubt proved a charming and interesting challenge to young men. In September 1898, she became pregnant with Leendert’s child. Such an occurrence was not unusual, either for the period or the couple’s social class. If pregnancy out of wedlock was not condoned, neither was it forcefully condemned. Few young men could afford to support a family; members of the Dutch working class often married late. As a result, it was not surprising that the young engaged in sex outside of marriage or that, in the days before birth control, young women often became pregnant. Rotterdam was a city full of people at loose ends in which traditional sexual mores were more respected than followed.

Nonetheless, a man was still expected to take responsibility for a woman he impregnated. The couple was married on December 22, 1898, in Schiedam. Leendert was twenty-two, Cornelia twenty-one. No one knows whether their marriage was strongly desired or merely the result of a brief sexual encounter. What is certain, however, is that the young couple immediately came under intense personal pressure. In 1899, six months after the wedding, de Kooning’s older sister, Marie, was born. Twin girls—Adriana and Cornelia—soon followed, in 1901, but they died days after their birth. Then came another daughter, Cornelia, in 1902, who died when she was eight months old. Willem de Kooning—the fifth child, but only the second to survive—was born in 1904, on April 24. By then, Cornelia had spent virtually all of her married life pregnant, either taking care of infants or burying them. She did so in a neighborhood where every day was a struggle: de Kooning’s family was part of a great mass of people hanging on week by week, trying to find their way in a newly evolving society.

Her husband had little energy to give to his family. Still in his twenties, he was working hard to establish his own business, hiring several employees to help him bottle beer for Heineken and other breweries. He also delivered the beer by means of dog and pony carts from his Vledhoekstraat concern to pubs throughout the district. Soon he expanded his business to bottle and distribute Elko lemonade as well. At the time of Willem’s birth, the de Koonings lived on Zaagmolenstraat, where the houses were slightly larger than those on the neighboring side streets—a subtle mark of Leendert’s rise in the world. But the house itself was anything but fancy. In de Kooning’s neighborhood, a man was rich if he owned a bicycle. (It was not unusual in the Rotterdam of 1910 for a man to walk two hours each way to work.) Most money was spent on necessities, though workers often blew their paychecks in the pubs—the only spots of warmth and brightness in the dank darkness of a Rotterdam winter, when the wind swept in from the North Sea. Meat was usually eaten once a week, on Sundays. The staple was potatoes flavored with lard from the butcher’s shop.

Housing for workers, including the house where the de Koonings lived, was typically built according to the same plan. An apartment consisted of two small rooms, one used as a parlor and the other as a kitchen and gathering spot for the family. In between the two rooms was an even smaller and windowless half-room—essentially a passageway—which served as a communal bedroom. On each side of the passageway there was a sleeping alcove, one for the parents and the other for the children; as many as three or four children might share a bed. Water came from a cold-water tap on the landing that was used by the two families sharing the floor. They also used a common toilet, located in a closet on the landing, which contained a bucket that was emptied manually. Since heat cost money, people were often cold. The de Koonings probably used a coal stove. Those still poorer relied on small cooking stoves to take the chill off the day; coins were inserted into a meter that turned on the gas. Baths were typically taken once a week at most, either at a public bath or at home, where each member of the family used the same tub of heated water. The hot water was purchased at the local grocery store and then hauled back home and up the steps to the apartment. Since washing clothes was difficult and expensive—it required buying hot water or hiring a laundress—clothes were rarely clean. Bedclothes, cumbersome and hard to dry, were almost never washed.

Descriere

The first major biography of Willem de Kooning captures both the life and work of this complex, romantic figure in American culture. Ten years in the making, and based on previously unseen letters and documents as well as on hundreds of interviews, this is a fresh, richly detailed, and masterful portrait.

Premii

- National Book Critics Circle Award Winner, 2004

- L.A. Times Book Prize Winner, 2004

- Pulitzer Prize Winner, 2005

- Ambassador Book Awards Winner, 2005