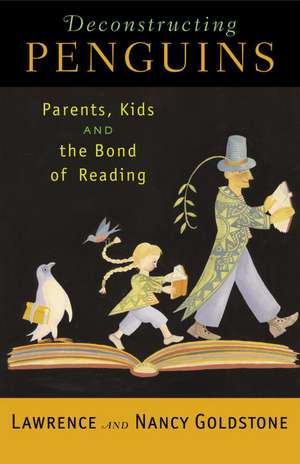

Deconstructing Penguins: Parents, Kids, and the Bond of Reading

Autor Nancy Goldstone, Lawrence Goldstoneen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2005

With the Goldstones help, parents can inspire kids’ lifelong love of reading by teaching them how to unlock a book’s hidden meaning. Featuring fun and incisive discussions of numerous children’s classics, this dynamic guide highlights key elements–theme, setting, character, point of view, climax, and conflict–and paves the way for meaningful conversations between parents and children.

“Best of all,” the Goldstones note, “you don’t need an advanced degree in English literature or forty hours a week of free time to effectively discuss a book with your child. This isn’t Crime and Punishment, it’s Charlotte’s Web.”

Preț: 103.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.86€ • 21.56$ • 16.68£

19.86€ • 21.56$ • 16.68£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812970289

ISBN-10: 0812970284

Pagini: 206

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0812970284

Pagini: 206

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

Chapter 1

PENGUINS 7, JETS 0

How We Got Started

The day we picked to hold our first parent-child book group at our local public library was Sunday, January 10, 1999. Like everything else about the book group, this date and the time—3:30 in the afternoon—had been carefully chosen after months of planning. The first Sunday in January seemed ideal because, as the school vacation had just ended, families would be home and the children would be refreshed. We chose late afternoon to minimize potential conflicts with the other myriad activities in which Connecticut second graders participate. We knew, for example, that the basketball league held its games on Saturday, ice-skating lessons were Sunday morning, the Sunday dance rehearsals for the Nutcracker were over, and soccer practice wouldn’t resume until early April.

It turned out, however, that we hadn’t thought of everything. The hapless New York Jets, a team that had not made the NFL play-offs in eight seasons or finished with a good enough record to host a play-off game in two decades, had that year miraculously achieved both. The young and hungry Jacksonville Jaguars were coming to town on, when else, January 10, and the winner would then meet the Denver Broncos for the right to go on to the Super Bowl.

Interest in the game approached the fanatical. The Meadowlands drew the second-largest crowd in the history of the stadium. (The largest had been for the pope.) Kick off was set for one p.m., which put the start of our little book group somewhere in the middle of the fourth quarter, when every living creature in the New York metropolitan area would be frozen in front of a television set.

At the last minute, however, it appeared that the fates might yet be with us. The game had descended into a rout and the Jets held a 31–14 lead at the beginning of the fourth quarter. By the time we piled into the car to head for the children’s department of the library with our books, markers, large writing pad, and enough cookies and juice to ensure the loyalty of our audience, we had brightened substantially. “No one needs to stay and see the end of that,” we said.

But no sooner had we backed out of the driveway—with the radio tuned to the game, of course—then Jacksonville scored a touchdown. During the five-minute trip to the library, they scored again. Before we could unload the car, the Jets had been intercepted and the potent Jacksonville offense had the ball once more.

“Hang on to your hats,” trumpeted the announcer. “This is gonna be a wild finish.”

With indefatigable if slightly forced good cheer, we trudged in and dragged our paraphernalia up the stairs to the meeting room. We set up an easel for the pad at the front of the room, laid out the snacks, and waited. Ten minutes later, we were still the only people in the room.

Finally, the door opened and a librarian stuck her head in. “Someone named Katherine’s mother called to say that they can’t make it this time but they’ll be here next time, and one of the other parents called to say that neither the father nor the son had read the book and did that matter?”

At 3:27, a mother and daughter walked in, looked around at the empty room, and wordlessly sat down. Soon another mother and daughter arrived and then, astoundingly, a father and daughter. They were followed closely by another father and his son. The first father and the second father exchanged a glance, the meaning of which was all too clear. Soon, we had ten second graders, each with a parent, four of whom were distressed fathers. When the last of the fathers entered, he gave the final, damning report.

“Down to a seven-point lead. Still four minutes to go.”

The dads all sunk a little lower in their seats, then, as one, turned to face us. We could read “This had better be worth it” written plainly on each of their faces. As they say in comedy . . . a tough room.

And so we launched into the afternoon’s offering: Mr. Popper’s Penguins.

Mr. Popper’s Penguins is about a housepainter who lives in a small town called Stillwater. Mr. Popper lives with Mrs. Popper and two little Poppers. He does not make a lot of money, possibly because he is so busy daydreaming about traveling to the Antarctic (a big deal in 1938 when this book was written). He couldn’t work in the winter, so he spent his time reading about explorers. As the story opens, he has just sent a letter to Admiral Drake, a famous Antarctic explorer, extolling the virtues of penguins. Admiral Drake responds by sending Mr. Popper a penguin of his very own.

Lots of humorous mishaps occur and a female penguin arrives, which quickly gives rise to ten additional penguins. Mr. Popper, in an attempt to afford all these penguins, takes them on the road as a stage act. They are wildly successful, earning the Poppers lots of money that they spend entirely on the penguins. Eventually, however, Mr. Popper and the penguins land in jail in New York from which they are rescued by Admiral Drake, who has just returned from his expedition. So impressed is Admiral Drake with Mr. Popper that he takes him on his next voyage. The book closes with an illustration of a smiling Mr. Popper in a fur hood, next to a penguin, looking over the railing of a ship.

“Welcome to the book group! Thank you all for coming,” we said, after everyone had gone around the room and introduced themselves and we’d made it clear to the kids that we were going to discuss the book for a while before we broke for snacks. “Books are like puzzles,” we began. “The author’s ideas are hidden and it is up to all of us to figure them out. Whenever you read a book you want to know what the book is really about, not what it’s about on the surface, not the story, but what’s underneath the story. . . .”

A little boy’s hand went up.

“Yes, Jeremy? Do you have an idea about what the book is really about?”

Jeremy (we’ve obviously changed all the names) was one of those kids you run into from time to time who appears to be actually a miniature adult. He was dressed in an Oxford shirt, V-neck sweater, corduroys, and what appeared to be little Rockport shoes. He stared intensely for a moment.

“Mr. Popper’s Penguins is about a man named Mr. Popper,” he reported. “Mr. Popper gets a penguin in the mail who he trains. Then he gets another penguin. They have babies. Then they go to New York.”

“That’s good, Jeremy, but that’s the story. We’re looking for what the author is trying to say underneath the story. What the story is really about. What do you think the story is really about?”

Jeremy nodded. “They get in trouble in New York. They even go to jail. Admiral Drake gets them out. Then Mr. Popper and the penguins go on the boat with Admiral Drake.”

“Yes, Jeremy, that’s very good.” Oh dear, we thought.

We tried some different, open-ended questions, like “Why do you think the authors chose penguins?” but it was proving impossible to move either the kids or the parents off the plot. After about twenty minutes, our worst fears were being realized: blank stares from the kids, restlessness from the parents, long silences, and two heavily perspiring moderators.

We continued to flounder until we asked, “The town that Mr. Popper lived in . . . what kind of a place was it? Why do you think the authors chose the name Stillwater? Was it just an accident?”

This had more success. One little girl said that she didn’t think it was an accident and we quickly (and gratefully) moved into a discussion of Stillwater. Everyone in the town except Mr. Popper, the kids quickly noticed, was “dull.” They were “boring,” “ordinary,” and “did what everyone else did.” “What do you think about people like that?” we asked. “How would you describe them in one word?”

Rebecca, a girl in the back, waved her hand furiously. “NORMAL,” she replied with triumph. The parents chuckled but shifted uneasily in their seats.

“What about Mr. Popper?” we went on. He was certainly not normal, the kids agreed. He was . . . they couldn’t seem to find the right word. So, on the easel, we wrote:

D _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A mother raised her hand. “Demented?” she offered.

“Nooooo.”

“Dumb?” suggested one of the little boys, obviously not a spelling whiz.

“Noooo.”

“What about ‘different’?” asked another mother.

“Yes! And what made him different?”

After a little more discussion it came out. Mr. Popper was different because he had a dream, and he was the only one in the town who did. What’s more, he had done something about it. He had followed his dream.

“Could this be a book about the importance of following your dreams?” we asked. “Was that what the book was really about?”

There was a slow nodding of heads.

“So,” we went on, “what did everyone think of this? Was it good to follow your dreams, or even to keep them?” The expression on each parent’s face changed. We went around the room, first asking each child, then each parent, “What is your dream?”

The kids, of course, had no trouble with this question. Although a couple had the very suburban dream of making a million dollars, there were also dreams of travel, adventure, and even world peace. When we came to Annabeth, a thoroughly adorable, cherubic little blond girl, she had no problem at all.

“My dream is that my brother gets eaten by a bear,” she said happily.

PENGUINS 7, JETS 0

How We Got Started

The day we picked to hold our first parent-child book group at our local public library was Sunday, January 10, 1999. Like everything else about the book group, this date and the time—3:30 in the afternoon—had been carefully chosen after months of planning. The first Sunday in January seemed ideal because, as the school vacation had just ended, families would be home and the children would be refreshed. We chose late afternoon to minimize potential conflicts with the other myriad activities in which Connecticut second graders participate. We knew, for example, that the basketball league held its games on Saturday, ice-skating lessons were Sunday morning, the Sunday dance rehearsals for the Nutcracker were over, and soccer practice wouldn’t resume until early April.

It turned out, however, that we hadn’t thought of everything. The hapless New York Jets, a team that had not made the NFL play-offs in eight seasons or finished with a good enough record to host a play-off game in two decades, had that year miraculously achieved both. The young and hungry Jacksonville Jaguars were coming to town on, when else, January 10, and the winner would then meet the Denver Broncos for the right to go on to the Super Bowl.

Interest in the game approached the fanatical. The Meadowlands drew the second-largest crowd in the history of the stadium. (The largest had been for the pope.) Kick off was set for one p.m., which put the start of our little book group somewhere in the middle of the fourth quarter, when every living creature in the New York metropolitan area would be frozen in front of a television set.

At the last minute, however, it appeared that the fates might yet be with us. The game had descended into a rout and the Jets held a 31–14 lead at the beginning of the fourth quarter. By the time we piled into the car to head for the children’s department of the library with our books, markers, large writing pad, and enough cookies and juice to ensure the loyalty of our audience, we had brightened substantially. “No one needs to stay and see the end of that,” we said.

But no sooner had we backed out of the driveway—with the radio tuned to the game, of course—then Jacksonville scored a touchdown. During the five-minute trip to the library, they scored again. Before we could unload the car, the Jets had been intercepted and the potent Jacksonville offense had the ball once more.

“Hang on to your hats,” trumpeted the announcer. “This is gonna be a wild finish.”

With indefatigable if slightly forced good cheer, we trudged in and dragged our paraphernalia up the stairs to the meeting room. We set up an easel for the pad at the front of the room, laid out the snacks, and waited. Ten minutes later, we were still the only people in the room.

Finally, the door opened and a librarian stuck her head in. “Someone named Katherine’s mother called to say that they can’t make it this time but they’ll be here next time, and one of the other parents called to say that neither the father nor the son had read the book and did that matter?”

At 3:27, a mother and daughter walked in, looked around at the empty room, and wordlessly sat down. Soon another mother and daughter arrived and then, astoundingly, a father and daughter. They were followed closely by another father and his son. The first father and the second father exchanged a glance, the meaning of which was all too clear. Soon, we had ten second graders, each with a parent, four of whom were distressed fathers. When the last of the fathers entered, he gave the final, damning report.

“Down to a seven-point lead. Still four minutes to go.”

The dads all sunk a little lower in their seats, then, as one, turned to face us. We could read “This had better be worth it” written plainly on each of their faces. As they say in comedy . . . a tough room.

And so we launched into the afternoon’s offering: Mr. Popper’s Penguins.

Mr. Popper’s Penguins is about a housepainter who lives in a small town called Stillwater. Mr. Popper lives with Mrs. Popper and two little Poppers. He does not make a lot of money, possibly because he is so busy daydreaming about traveling to the Antarctic (a big deal in 1938 when this book was written). He couldn’t work in the winter, so he spent his time reading about explorers. As the story opens, he has just sent a letter to Admiral Drake, a famous Antarctic explorer, extolling the virtues of penguins. Admiral Drake responds by sending Mr. Popper a penguin of his very own.

Lots of humorous mishaps occur and a female penguin arrives, which quickly gives rise to ten additional penguins. Mr. Popper, in an attempt to afford all these penguins, takes them on the road as a stage act. They are wildly successful, earning the Poppers lots of money that they spend entirely on the penguins. Eventually, however, Mr. Popper and the penguins land in jail in New York from which they are rescued by Admiral Drake, who has just returned from his expedition. So impressed is Admiral Drake with Mr. Popper that he takes him on his next voyage. The book closes with an illustration of a smiling Mr. Popper in a fur hood, next to a penguin, looking over the railing of a ship.

“Welcome to the book group! Thank you all for coming,” we said, after everyone had gone around the room and introduced themselves and we’d made it clear to the kids that we were going to discuss the book for a while before we broke for snacks. “Books are like puzzles,” we began. “The author’s ideas are hidden and it is up to all of us to figure them out. Whenever you read a book you want to know what the book is really about, not what it’s about on the surface, not the story, but what’s underneath the story. . . .”

A little boy’s hand went up.

“Yes, Jeremy? Do you have an idea about what the book is really about?”

Jeremy (we’ve obviously changed all the names) was one of those kids you run into from time to time who appears to be actually a miniature adult. He was dressed in an Oxford shirt, V-neck sweater, corduroys, and what appeared to be little Rockport shoes. He stared intensely for a moment.

“Mr. Popper’s Penguins is about a man named Mr. Popper,” he reported. “Mr. Popper gets a penguin in the mail who he trains. Then he gets another penguin. They have babies. Then they go to New York.”

“That’s good, Jeremy, but that’s the story. We’re looking for what the author is trying to say underneath the story. What the story is really about. What do you think the story is really about?”

Jeremy nodded. “They get in trouble in New York. They even go to jail. Admiral Drake gets them out. Then Mr. Popper and the penguins go on the boat with Admiral Drake.”

“Yes, Jeremy, that’s very good.” Oh dear, we thought.

We tried some different, open-ended questions, like “Why do you think the authors chose penguins?” but it was proving impossible to move either the kids or the parents off the plot. After about twenty minutes, our worst fears were being realized: blank stares from the kids, restlessness from the parents, long silences, and two heavily perspiring moderators.

We continued to flounder until we asked, “The town that Mr. Popper lived in . . . what kind of a place was it? Why do you think the authors chose the name Stillwater? Was it just an accident?”

This had more success. One little girl said that she didn’t think it was an accident and we quickly (and gratefully) moved into a discussion of Stillwater. Everyone in the town except Mr. Popper, the kids quickly noticed, was “dull.” They were “boring,” “ordinary,” and “did what everyone else did.” “What do you think about people like that?” we asked. “How would you describe them in one word?”

Rebecca, a girl in the back, waved her hand furiously. “NORMAL,” she replied with triumph. The parents chuckled but shifted uneasily in their seats.

“What about Mr. Popper?” we went on. He was certainly not normal, the kids agreed. He was . . . they couldn’t seem to find the right word. So, on the easel, we wrote:

D _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

A mother raised her hand. “Demented?” she offered.

“Nooooo.”

“Dumb?” suggested one of the little boys, obviously not a spelling whiz.

“Noooo.”

“What about ‘different’?” asked another mother.

“Yes! And what made him different?”

After a little more discussion it came out. Mr. Popper was different because he had a dream, and he was the only one in the town who did. What’s more, he had done something about it. He had followed his dream.

“Could this be a book about the importance of following your dreams?” we asked. “Was that what the book was really about?”

There was a slow nodding of heads.

“So,” we went on, “what did everyone think of this? Was it good to follow your dreams, or even to keep them?” The expression on each parent’s face changed. We went around the room, first asking each child, then each parent, “What is your dream?”

The kids, of course, had no trouble with this question. Although a couple had the very suburban dream of making a million dollars, there were also dreams of travel, adventure, and even world peace. When we came to Annabeth, a thoroughly adorable, cherubic little blond girl, she had no problem at all.

“My dream is that my brother gets eaten by a bear,” she said happily.

Recenzii

“This insightful book can be immensely helpful as we strive to resurrect literacy among children. With Deconstructing Penguins, kids and their parents can share in the enlightened adventure of active interpretation during reading. As a result, they will become more avid and able interpreters of their own life experiences.”

–Mel Levine, M. D., author of A Mind at a Time

“Not just the single best book on leading a book discussion group, Deconstructing Penguins is also about how to dig a tunnel into the heart of a book. In my ideal world, every reading teacher would trash that boring classroom text and adopt this book as a curriculum bible.”

–Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook

“This wonderful, easy-to-read guide will be a tremendous resource for librarians, teachers, and parents who want to help kids experience the joys of children’s literature.”

–Sally G. Reed, executive director, Friends of Libraries U.S.A.

–Mel Levine, M. D., author of A Mind at a Time

“Not just the single best book on leading a book discussion group, Deconstructing Penguins is also about how to dig a tunnel into the heart of a book. In my ideal world, every reading teacher would trash that boring classroom text and adopt this book as a curriculum bible.”

–Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook

“This wonderful, easy-to-read guide will be a tremendous resource for librarians, teachers, and parents who want to help kids experience the joys of children’s literature.”

–Sally G. Reed, executive director, Friends of Libraries U.S.A.

Descriere

The leaders of an acclaimed parent-child book group reveal their method for creating active, engaged readers.

Notă biografică

Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone