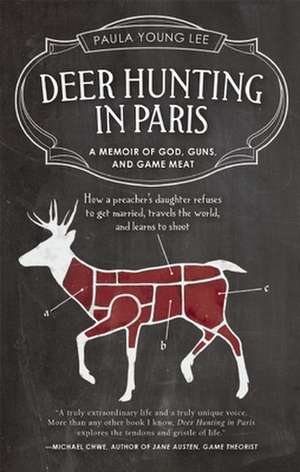

Deer Hunting in Paris: A Memoir of God, Guns, and Game Meat: Travelers' Tales Guides

Autor Paula Young Leeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 noi 2013

What happens when a Korean-American preacher’s kid refuses to get married, travels the world, and quits being vegetarian? She meets her polar opposite on an online dating site while sitting at a café in Paris, France and ends up in Paris, Maine, learning how to hunt. A memoir and a cookbook with recipes that skewer human foibles and celebrates DIY food culture, Deer Hunting in Paris is an unexpectedly funny exploration of a vanishing way of life in a complex cosmopolitan world. Sneezing madly from hay fever, Lee recovers her roots in rural Maine by running after a headless chicken, learning how to sight in a rifle, shooting skeet, and butchering animals. Along the way, she figures out how to keep her boyfriend’s conservative Republican family from “mistaking” her for a deer and shooting her at the clothesline.

Din seria Travelers' Tales Guides

-

Preț: 104.70 lei

Preț: 104.70 lei -

Preț: 117.32 lei

Preț: 117.32 lei -

Preț: 111.14 lei

Preț: 111.14 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 110.08 lei

Preț: 110.08 lei -

Preț: 112.78 lei

Preț: 112.78 lei -

Preț: 109.67 lei

Preț: 109.67 lei - 22%

Preț: 57.87 lei

Preț: 57.87 lei - 20%

Preț: 71.49 lei

Preț: 71.49 lei - 22%

Preț: 58.50 lei

Preț: 58.50 lei - 21%

Preț: 81.30 lei

Preț: 81.30 lei - 22%

Preț: 57.87 lei

Preț: 57.87 lei - 21%

Preț: 60.01 lei

Preț: 60.01 lei - 20%

Preț: 61.06 lei

Preț: 61.06 lei - 20%

Preț: 61.50 lei

Preț: 61.50 lei - 21%

Preț: 69.63 lei

Preț: 69.63 lei - 20%

Preț: 60.89 lei

Preț: 60.89 lei - 21%

Preț: 70.70 lei

Preț: 70.70 lei

Preț: 75.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 113

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.39€ • 15.03$ • 11.91£

14.39€ • 15.03$ • 11.91£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781609520809

ISBN-10: 1609520807

Pagini: 303

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Travelers' Tales Guides

Seria Travelers' Tales Guides

ISBN-10: 1609520807

Pagini: 303

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Travelers' Tales Guides

Seria Travelers' Tales Guides

Recenzii

Winner of the 2014 Lowell Thomas Award for Best Travel Book

In honoring Paula Young Lee's work, the judges said: "Eudora Welty, who believes all good writing must have it, speaks of the sound of a voice. And what a voice here! Resonant with images and descriptions, detailed observation and reporting, it soars — from a coot recipe to church suppers. Paula Young Lee saw a lot of the latter because her father, who came to this country from Korea with her mother after the war, served as a Methodist minister in various small town churches in Maine. Growing up there instilled in her a love of hunting, a match for her interest in cooking."

"Paula Young Lee has the best 'Food & Hunting' book of the season: Deer Hunting in Paris."

— Stephen Bodio

"Once I starting flipping through its pages I found myself reading it cover to cover...[Lee] writes well and tells a good story."

— Marion Nestle, author of Eat, Drink, Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Food Politics, 2013

"Pour yourself a cup of tea, curl up on the couch, and open up Paula Young Lee’s latest book, Deer Hunting in Paris: A Memoir of God, Guns, and Game Meat. And be prepared to laugh out loud. Often."

— Marjorie Moss, contributor to HuntingLife

"[Lee's] unsentimental take on family relationships, rural and city cultures, red and blue Americas, and, ultimately, death, human and animal alike — [is] a gratifying relief from conventional thought. Deer hunting in Paris? I'd follow Lee anywhere."

— Alison Pearlman, author of Smart Casual: The Transformation of Gourmet Restaurant Style in America, 2013

“Paula Young Lee’s memoir, Deer Hunting in Paris, bursts with wit, recipes, and unexpected juxtapositions. I grew up Korean American in Alabama, but Paula grew up Korean American in Maine, which is even stranger. I did not go on to explore Paris and moose hunting like Paula did, but her memoir, which is unexpectedly moving, makes me wish I had. A truly extraordinary life and a truly unique voice. More than any other book I know, Deer Hunting in Paris explores the tendons and gristle of life.”

— Michael Chwe, author of Jane Austen, Game Theorist

“From the rugged backwoods of Maine to the streets of Paris, Paula Young Lee takes you on an unexpected journey. Through deep insight, arresting imagery, and deft turns of phrase, she reveals the meat, blood, and bone of our hungers, dark and true.”

— Tara Austen Weaver, author of The Butcher & The Vegetarian

“Not many narratives have you laughing, wincing, and weeping at the same time. Deer Hunting in Paris is pure prose genius. Smart and smart-alecky, a delight on every page.”

— Gary Buslik, author of A Rotten Person Travels the Caribbean and Akhmed and the Atomic Matzo Balls

“Paula Young Lee is M.F.K. Fisher with a gun, Julia Child prepping roadkill.”

— Marcy Gordon, editor, Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana

“Deer Hunting in Paris is a story of hunger and faith, and faith in hunger. But there’s more to it than that: a frenetic electricity, a stumbling toward an illusion of arrival that’s hard to put a finger on. Paula Young Lee’s memoir is the stuff of sumptuous and bloodthirsty parable, a story at once new and strange, and yet engrained, guiding us with searing wit through the chambers of our lives. In her commentary on contemporary culture, her catalogue of references that shift from ancient to pop in the blink of an eye, this is a memoir that proves and interrogates the wild interconnectedness of things, especially those that may at first seem glaringly dissimilar. Lee moves us from Maine to France and back again, whirls us among Jesus and Kafka, IKEA and The Big Buck Club, love, shotguns, longing, and death. ‘The dying,’ she tells us, ‘have epiphaniesand enemas.’ Rarely has such a spectrum of quirky meditations been so funny, and so true. The result is a tale that makes you laugh, scratch your head, rock your heart back from the breaking, and ultimately, exhale, exhilarated, having just learned that the weirdest arenas in our lives are often the most beautiful.”

— Matthew Gavin Frank, author of Preparing the Ghost, Pot Farm, and Barolo

“I have a new favorite writer—I love this book. Like Spalding Gray before her, Paula Young Lee has written an endearingly neurotic monologue full of cleaver-sharp, side-splitting storytelling. There are books (think Bill Bryson, J. Maarten Troost, Tahir Shah) that contain an ultimate moment that for years I read aloud to friends, but Deer Hunting in Paris is an entire book of such moments. I phoned friends and family and stopped strangers to read aloud some of Paula’s moments: her nose nestled between her boyfriend’s butt cheeks as they train for the wife-carrying competition, her childhood dream that Turkish delight is 100% giblets, trying on a camouflage bikini (while ammo shopping) that turns her into both a wallflower and a butterball, a wedding day pig roast with a guy nicknamed Smeg, short for smegma. What I wasn’t expecting in this witty romp was a wisdom and way of looking at life and death that would make this the most personally profound book I’ve ever read. My life-long all-consuming terror of death was bizarrely put out of its misery with Lee’s rational portrait of the inevitable for all of us creatures as she deftly handles flesh for feasting.”

— Kirsten Koza, author of Lost in Moscow: A Brat in the USSR

“Paula Young Lee takes us on an intriguing whirl through a Paris most of us have never seen—a Paris of Republicans, rifle-toting New Englanders, and riotous tales of hunting. Your stomach will ache from laughter and hunger at the same time.”

— David Farley, author of An Irreverent Curiosity

Book of the Week, 22 Nov. 2013, AnyNewBooks

On Paula Young Lee's writing:

“Intelligent without snobbery, poignant without sappiness, and hilarious without end...[it will] never get out of your head.”

— Ron Cooper, author of critically acclaimed novels, Hume’s Fork and Purple Jesus

“Lee’s characters are captivating, her prose crystalline, her storytelling worth your precious time."

— Garrison Somers, Editor-in-Chief, The Blotter Magazine

In honoring Paula Young Lee's work, the judges said: "Eudora Welty, who believes all good writing must have it, speaks of the sound of a voice. And what a voice here! Resonant with images and descriptions, detailed observation and reporting, it soars — from a coot recipe to church suppers. Paula Young Lee saw a lot of the latter because her father, who came to this country from Korea with her mother after the war, served as a Methodist minister in various small town churches in Maine. Growing up there instilled in her a love of hunting, a match for her interest in cooking."

"Paula Young Lee has the best 'Food & Hunting' book of the season: Deer Hunting in Paris."

— Stephen Bodio

"Once I starting flipping through its pages I found myself reading it cover to cover...[Lee] writes well and tells a good story."

— Marion Nestle, author of Eat, Drink, Vote: An Illustrated Guide to Food Politics, 2013

"Pour yourself a cup of tea, curl up on the couch, and open up Paula Young Lee’s latest book, Deer Hunting in Paris: A Memoir of God, Guns, and Game Meat. And be prepared to laugh out loud. Often."

— Marjorie Moss, contributor to HuntingLife

"[Lee's] unsentimental take on family relationships, rural and city cultures, red and blue Americas, and, ultimately, death, human and animal alike — [is] a gratifying relief from conventional thought. Deer hunting in Paris? I'd follow Lee anywhere."

— Alison Pearlman, author of Smart Casual: The Transformation of Gourmet Restaurant Style in America, 2013

“Paula Young Lee’s memoir, Deer Hunting in Paris, bursts with wit, recipes, and unexpected juxtapositions. I grew up Korean American in Alabama, but Paula grew up Korean American in Maine, which is even stranger. I did not go on to explore Paris and moose hunting like Paula did, but her memoir, which is unexpectedly moving, makes me wish I had. A truly extraordinary life and a truly unique voice. More than any other book I know, Deer Hunting in Paris explores the tendons and gristle of life.”

— Michael Chwe, author of Jane Austen, Game Theorist

“From the rugged backwoods of Maine to the streets of Paris, Paula Young Lee takes you on an unexpected journey. Through deep insight, arresting imagery, and deft turns of phrase, she reveals the meat, blood, and bone of our hungers, dark and true.”

— Tara Austen Weaver, author of The Butcher & The Vegetarian

“Not many narratives have you laughing, wincing, and weeping at the same time. Deer Hunting in Paris is pure prose genius. Smart and smart-alecky, a delight on every page.”

— Gary Buslik, author of A Rotten Person Travels the Caribbean and Akhmed and the Atomic Matzo Balls

“Paula Young Lee is M.F.K. Fisher with a gun, Julia Child prepping roadkill.”

— Marcy Gordon, editor, Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana

“Deer Hunting in Paris is a story of hunger and faith, and faith in hunger. But there’s more to it than that: a frenetic electricity, a stumbling toward an illusion of arrival that’s hard to put a finger on. Paula Young Lee’s memoir is the stuff of sumptuous and bloodthirsty parable, a story at once new and strange, and yet engrained, guiding us with searing wit through the chambers of our lives. In her commentary on contemporary culture, her catalogue of references that shift from ancient to pop in the blink of an eye, this is a memoir that proves and interrogates the wild interconnectedness of things, especially those that may at first seem glaringly dissimilar. Lee moves us from Maine to France and back again, whirls us among Jesus and Kafka, IKEA and The Big Buck Club, love, shotguns, longing, and death. ‘The dying,’ she tells us, ‘have epiphaniesand enemas.’ Rarely has such a spectrum of quirky meditations been so funny, and so true. The result is a tale that makes you laugh, scratch your head, rock your heart back from the breaking, and ultimately, exhale, exhilarated, having just learned that the weirdest arenas in our lives are often the most beautiful.”

— Matthew Gavin Frank, author of Preparing the Ghost, Pot Farm, and Barolo

“I have a new favorite writer—I love this book. Like Spalding Gray before her, Paula Young Lee has written an endearingly neurotic monologue full of cleaver-sharp, side-splitting storytelling. There are books (think Bill Bryson, J. Maarten Troost, Tahir Shah) that contain an ultimate moment that for years I read aloud to friends, but Deer Hunting in Paris is an entire book of such moments. I phoned friends and family and stopped strangers to read aloud some of Paula’s moments: her nose nestled between her boyfriend’s butt cheeks as they train for the wife-carrying competition, her childhood dream that Turkish delight is 100% giblets, trying on a camouflage bikini (while ammo shopping) that turns her into both a wallflower and a butterball, a wedding day pig roast with a guy nicknamed Smeg, short for smegma. What I wasn’t expecting in this witty romp was a wisdom and way of looking at life and death that would make this the most personally profound book I’ve ever read. My life-long all-consuming terror of death was bizarrely put out of its misery with Lee’s rational portrait of the inevitable for all of us creatures as she deftly handles flesh for feasting.”

— Kirsten Koza, author of Lost in Moscow: A Brat in the USSR

“Paula Young Lee takes us on an intriguing whirl through a Paris most of us have never seen—a Paris of Republicans, rifle-toting New Englanders, and riotous tales of hunting. Your stomach will ache from laughter and hunger at the same time.”

— David Farley, author of An Irreverent Curiosity

Book of the Week, 22 Nov. 2013, AnyNewBooks

On Paula Young Lee's writing:

“Intelligent without snobbery, poignant without sappiness, and hilarious without end...[it will] never get out of your head.”

— Ron Cooper, author of critically acclaimed novels, Hume’s Fork and Purple Jesus

“Lee’s characters are captivating, her prose crystalline, her storytelling worth your precious time."

— Garrison Somers, Editor-in-Chief, The Blotter Magazine

Extras

Prologue

Parishioners believed he could heal them with his hands. As a kid, I knew my father was different, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a preacher. His legs were shriveled down to bone and he walked funny, sometimes with a cane. His face beamed. He forgot to eat. He liked Maine, because the rocky terrain reminded him of home. At first, there were four of us, and then there were five: my father, my mother, my brother, my sister, and me in the middle. My older brother and I fought mean and hard, locked in a death match from the day I was born. Blissfully oblivious to the slugfest, my baby sister sat back and let the adults fuss over her. She was the pretty one. Together, the three of us practiced our musical instruments, spoke English at home, and got straight As in school. We grew up ringing church bells every Sunday, pulling down the ropes and flying up into the belfry. My sister and I sang in the choir as my brother pummeled toccatas and fugues out of the organ. There was Sunday School, bible study, and neighborly visits to the nursing home, but the part I liked about church was Christmas, and the fancy food.

I could cook before I could read. I could read before I was four, because I was mad that my older brother was Sacred Cow Oldest Number One Son, and he got to do everything first. From birth, I knew the weight of karmic injustice, and I knew what that meant thanks to those theological discussions at dinner. Not only would I never be older than him, he would always be smarter. And a boy. His Korean name began with "Ho," which in English means "Great." Humph. What's so great about him? “How come he gets to be a Ho?" I would howl, a pudgy ball of rage stamping angrily on tabletops. "It's not fair! I want to be a Ho!" Sure, he could make electric generators out of Tinker Toy sets, but I could make layer cakes, and I had friends. So there. Cakes win.

With ‘Auntie’ Ima the babysitter, I baked coffee cakes and apple pies. With my mother, I made mondu (dumplings) and nangmyun (noodles). The church ladies taught me how to knead dough and whip cream. I didn’t eat the goodies that I made. Nothing about me was sweet, including my teeth. My great food love was meat, the kind of meat that demands a sharp knife and a taste for blood. We never seemed to have much. I suppose we were dirt poor, but so was everyone else. Poor was normal. Poverty was too. Instead of plastic reindeer glowing on front yards, winter meant gutted deer hanging off porch roofs, hovering lightly in the blue air, black noses sniffing the ground. I’d extend a searching hand, flicking away flakes, and stick my nose in where it didn’t belong. Like magic, the deer’s length and heft became food and it was Good, the body and blood of Amen, a serving of flesh tying the community together through the violence of hunger.

Deer and hunter walked the same paths through the woods. I wanted to follow them.

Sunday dinners at the parsonage, guests would discard the gristle, the cartilage, the marrow, and the rind, all the stuff that pale priests and thickening colonels refused to touch in mixed company. I’d serve and clear the table, acting the perfect hostess as my baby sister sat there, cheerfully basking in her cuteness, and my savant brother played young Christ before the Elders. Back in the kitchen where no one would see me, I’d grab bones off dirtied plates and gnaw off that bulbous white knob at the end, my favorite part, a tasty tidbit that only appeared after the commonplace had been excavated. Lollipops for carnivores. It wasn’t meat that I really craved. I loved liver and heart, along with the tangled tissues that connected the big sheets of muscle together. The offal fed to animals was the stuff that I wanted chew, because I was more contrary than Mary, not halo Mary mother of God but the stubborn one that ruled Scotland before she lost her head.

So, Miss Mary Mary, how does your garden grow?

Oh, very well, thanks to the corpse of my murdered husband fertilizing the marigolds.

Nursery rhymes mask vicious politics. So does a well cooked meal.

A giblet was a meat pacifier, rubbery and melting at the same time. It resisted. It put up a fight. I cherished its toughness, as I gnawed and glowered in the kitchen, a fat feral gnome surrounded by the aromas of love and yeast and holy ghosts I did not believe in.

It does not matter if you believe in God, my father said with infuriating patience. Because God believes in you.

But I’m an iconoclast, I protested loudly, trying out my interesting new word.

So was Martin Luther, my father responded placidly. You’re a protestant through and through.

No I’m not!

Yes, you are.

And so I was boxed into a corner.

+++

Around the age of eight, I read Anna Karenina, the greatest novel ever written about a French-speaking Russian adulteress. I didn’t grasp the big themes, but for reasons I could not explain, the story of her tragic affair put me off meat for almost two decades. (Leo Tolstoy, I later learned, was both a devout Christian and vegetarian who drove his wife crazy. I suspect that had something to do with it.) My parents did not understand my decision to become a vegetarian, especially since the fresh flesh of animals was the only food group I could safely eat. From almonds to zucchini, just about everything else produced unfortunate effects, ranging from discordant fits of sneezing to bouts of hyperactive screaming. Some of my earliest memories are of intense itching and being swaddled so I wouldn’t claw myself to bits. Using an old-fashioned washboard and wringer, my parents rinsed out daily dozens of cloth diapers dripping with diarrhea and frowned in confusion when my perpetual rash got infected because I was allergic to detergents.

Fish? – Allergic! Cats? – Allergic! Sunshine? – Allergic! Etc. For all that I was a surprisingly functional little kid, but being allergic to everything sets up a relationship to the world that is inescapably adversarial. You cannot take anything for granted, including God’s purported benevolence as he watches over the (hmmm…tasty?) sparrows. Me, I was being eyeballed by the Almighty of Abraham, the judgmental Old Testament God that was busy smiting sinners and turning unworthy women into pillars of salt. Sulkily sucking my thumb (-- not allergic. Safe!), I used to imagine that I was Lot’s wife reincarnated, which explained both my liking for salt as well as my instinctive aversion to marriage. It pissed me off that she was “Lot’s wife” instead of, say, Veronica or Betty. These things register when you come from a culture that keeps the family unit sorted by calling you “Oldest Daughter.”

And yes, I know that Christians don’t reincarnate. That’s for Buddhists. Sorry.

Korean parents don’t understand “vegetarian.” In general, survivors who immigrate due to war find it odd when someone rejects a perfectly acceptable food group just because. What, no Spam with your eggs? But you love Spam! Dried squid is good! American chop suey is good! Aigu, aigu, my mother wailed. What is wrong with Oldest Daughter? No eight-year-old has a food philosophy. Refusing to eat meat was just something I had to do. In retrospect, I am glad that my father was assigned to churches in tiny towns where psychiatrists did not practice, because in rural America, food allergies are still namby-pamby liberal myths, setting me up for exceedingly vexed relationships with human authority figures who insisted on making me eat home-grown tomatoes and hand-caught lobsters and did not connect the dots when I began crossly exploding into hives. Adding insult to injury, most of my allergies weren’t fatal. That would have been interesting. No, mine were the kind that merely damned me to the perpetual motions of misery: wiping snot off my nose, knobbling watery eyes, watching my tongue swell, lather, rinse, repeat. Boring!

My dream was to get away from grownups telling me to stop sneezing. My mantra was self-sufficiency, and I started going after it as soon as I was able to crawl. The faster I could learn to fend for myself, the sooner I could set out on my own. I started by running the back roads of Maine, observing the quirks of the local ecology: fiddleheads to eat, pine cones for weapons, and beer cans worth money if you redeemed them. I ran to get out of the house. I ran because I was jumping out of my skin. I ran so I could be alone, running on restless legs that walked in and out of homerooms, kicking bullies in the schoolyard and slamming my brother in the shins. My sister just sat back and watched me fight, blinking bewildered black eyes and sucking contentedly on cookies. She could never figure out why I was so furious all the time. She was born with grace. Predictably, her Korean name, Young-Mi, means "flower." Mine is Young-Nan. It means "egg."

“Young Mi-ya!” my mother would call up the stairs to my baby sister. To me: “Young-Nanny! Young Nanneeeee! Wake up your sister! You’re late for school!”

“Not ‘Young Nanny’,” I’d glower, and pull my snoring sister out of bed. As I got her ready for school, my blissfully sleeping sister would drool lavishly on my hand-me-down shoes.

Having a crippled older religious man as your father means your parents start out gods with feet of clay, and they become mere mortals as soon as you’re on solid food. The emotional launch into adulthood starts long before biology catches up with you. By the time I was teenager, between convulsive bouts of school, I’d begun waddling around small continents in sensible shoes, carting around my precious packet of toilet paper, sunscreen, and a jar of antihistamines. Disappearing for months and years, I burrowed into cities such as Florence, London, and Seoul but mostly Paris, a place that bears remarkably little resemblance to the romantic fantasies spun about it. This was fine with me. I wasn’t looking for love, drugs, yoga classes or any other “girl” narratives attached to stories about free spirits bravely traveling alone. When your trips abroad are being paid for by your father/divorce settlement/publisher, you’re not free. You’re expensive. Besides which, I grew up foreign in a native country. From birth, you’re an alien being, a world traveler by default: dropped down the chimney by migratory storks.

In cities called Cosmopolitan, everyone is born of a bird. We are all the same kind, fine in our feathers but naked in our skins. Not all birds fly. Not all birds can.

There is no homing device in my head.

My mother prayed I’d run into a nice Korean boy and start making legally wedded babies. My father hoped my peregrinations would put me on the road to Damascus, where I’d see God’s truth and start preaching His word, writing letters to the Corinthians and voting Republican. I was St. Paul’s namesake, after all. My parents had been expecting a boy, because apparently I’d been one in the womb. That’s what the baby doctors told them. I chose to disagree. Given my conversion when I saw the light, my destiny was to become an apostle. Failing that, my father was thinking accountant. A good career choice for girls.

Ah, but in Latin, Paul also means “little,” which is what I ended up being. Or rather, very short. Sometimes wee, mostly Weeble. The wobble was incontestable.

I knew my mind, and it was strange. It disagreed with my body, and my body struggled to get away. Amazingly, wherever my body went, my brain went too, barking, “No meat for you!”

Parishioners believed he could heal them with his hands. As a kid, I knew my father was different, and it had nothing to do with the fact that he was a preacher. His legs were shriveled down to bone and he walked funny, sometimes with a cane. His face beamed. He forgot to eat. He liked Maine, because the rocky terrain reminded him of home. At first, there were four of us, and then there were five: my father, my mother, my brother, my sister, and me in the middle. My older brother and I fought mean and hard, locked in a death match from the day I was born. Blissfully oblivious to the slugfest, my baby sister sat back and let the adults fuss over her. She was the pretty one. Together, the three of us practiced our musical instruments, spoke English at home, and got straight As in school. We grew up ringing church bells every Sunday, pulling down the ropes and flying up into the belfry. My sister and I sang in the choir as my brother pummeled toccatas and fugues out of the organ. There was Sunday School, bible study, and neighborly visits to the nursing home, but the part I liked about church was Christmas, and the fancy food.

I could cook before I could read. I could read before I was four, because I was mad that my older brother was Sacred Cow Oldest Number One Son, and he got to do everything first. From birth, I knew the weight of karmic injustice, and I knew what that meant thanks to those theological discussions at dinner. Not only would I never be older than him, he would always be smarter. And a boy. His Korean name began with "Ho," which in English means "Great." Humph. What's so great about him? “How come he gets to be a Ho?" I would howl, a pudgy ball of rage stamping angrily on tabletops. "It's not fair! I want to be a Ho!" Sure, he could make electric generators out of Tinker Toy sets, but I could make layer cakes, and I had friends. So there. Cakes win.

With ‘Auntie’ Ima the babysitter, I baked coffee cakes and apple pies. With my mother, I made mondu (dumplings) and nangmyun (noodles). The church ladies taught me how to knead dough and whip cream. I didn’t eat the goodies that I made. Nothing about me was sweet, including my teeth. My great food love was meat, the kind of meat that demands a sharp knife and a taste for blood. We never seemed to have much. I suppose we were dirt poor, but so was everyone else. Poor was normal. Poverty was too. Instead of plastic reindeer glowing on front yards, winter meant gutted deer hanging off porch roofs, hovering lightly in the blue air, black noses sniffing the ground. I’d extend a searching hand, flicking away flakes, and stick my nose in where it didn’t belong. Like magic, the deer’s length and heft became food and it was Good, the body and blood of Amen, a serving of flesh tying the community together through the violence of hunger.

Deer and hunter walked the same paths through the woods. I wanted to follow them.

Sunday dinners at the parsonage, guests would discard the gristle, the cartilage, the marrow, and the rind, all the stuff that pale priests and thickening colonels refused to touch in mixed company. I’d serve and clear the table, acting the perfect hostess as my baby sister sat there, cheerfully basking in her cuteness, and my savant brother played young Christ before the Elders. Back in the kitchen where no one would see me, I’d grab bones off dirtied plates and gnaw off that bulbous white knob at the end, my favorite part, a tasty tidbit that only appeared after the commonplace had been excavated. Lollipops for carnivores. It wasn’t meat that I really craved. I loved liver and heart, along with the tangled tissues that connected the big sheets of muscle together. The offal fed to animals was the stuff that I wanted chew, because I was more contrary than Mary, not halo Mary mother of God but the stubborn one that ruled Scotland before she lost her head.

So, Miss Mary Mary, how does your garden grow?

Oh, very well, thanks to the corpse of my murdered husband fertilizing the marigolds.

Nursery rhymes mask vicious politics. So does a well cooked meal.

A giblet was a meat pacifier, rubbery and melting at the same time. It resisted. It put up a fight. I cherished its toughness, as I gnawed and glowered in the kitchen, a fat feral gnome surrounded by the aromas of love and yeast and holy ghosts I did not believe in.

It does not matter if you believe in God, my father said with infuriating patience. Because God believes in you.

But I’m an iconoclast, I protested loudly, trying out my interesting new word.

So was Martin Luther, my father responded placidly. You’re a protestant through and through.

No I’m not!

Yes, you are.

And so I was boxed into a corner.

+++

Around the age of eight, I read Anna Karenina, the greatest novel ever written about a French-speaking Russian adulteress. I didn’t grasp the big themes, but for reasons I could not explain, the story of her tragic affair put me off meat for almost two decades. (Leo Tolstoy, I later learned, was both a devout Christian and vegetarian who drove his wife crazy. I suspect that had something to do with it.) My parents did not understand my decision to become a vegetarian, especially since the fresh flesh of animals was the only food group I could safely eat. From almonds to zucchini, just about everything else produced unfortunate effects, ranging from discordant fits of sneezing to bouts of hyperactive screaming. Some of my earliest memories are of intense itching and being swaddled so I wouldn’t claw myself to bits. Using an old-fashioned washboard and wringer, my parents rinsed out daily dozens of cloth diapers dripping with diarrhea and frowned in confusion when my perpetual rash got infected because I was allergic to detergents.

Fish? – Allergic! Cats? – Allergic! Sunshine? – Allergic! Etc. For all that I was a surprisingly functional little kid, but being allergic to everything sets up a relationship to the world that is inescapably adversarial. You cannot take anything for granted, including God’s purported benevolence as he watches over the (hmmm…tasty?) sparrows. Me, I was being eyeballed by the Almighty of Abraham, the judgmental Old Testament God that was busy smiting sinners and turning unworthy women into pillars of salt. Sulkily sucking my thumb (-- not allergic. Safe!), I used to imagine that I was Lot’s wife reincarnated, which explained both my liking for salt as well as my instinctive aversion to marriage. It pissed me off that she was “Lot’s wife” instead of, say, Veronica or Betty. These things register when you come from a culture that keeps the family unit sorted by calling you “Oldest Daughter.”

And yes, I know that Christians don’t reincarnate. That’s for Buddhists. Sorry.

Korean parents don’t understand “vegetarian.” In general, survivors who immigrate due to war find it odd when someone rejects a perfectly acceptable food group just because. What, no Spam with your eggs? But you love Spam! Dried squid is good! American chop suey is good! Aigu, aigu, my mother wailed. What is wrong with Oldest Daughter? No eight-year-old has a food philosophy. Refusing to eat meat was just something I had to do. In retrospect, I am glad that my father was assigned to churches in tiny towns where psychiatrists did not practice, because in rural America, food allergies are still namby-pamby liberal myths, setting me up for exceedingly vexed relationships with human authority figures who insisted on making me eat home-grown tomatoes and hand-caught lobsters and did not connect the dots when I began crossly exploding into hives. Adding insult to injury, most of my allergies weren’t fatal. That would have been interesting. No, mine were the kind that merely damned me to the perpetual motions of misery: wiping snot off my nose, knobbling watery eyes, watching my tongue swell, lather, rinse, repeat. Boring!

My dream was to get away from grownups telling me to stop sneezing. My mantra was self-sufficiency, and I started going after it as soon as I was able to crawl. The faster I could learn to fend for myself, the sooner I could set out on my own. I started by running the back roads of Maine, observing the quirks of the local ecology: fiddleheads to eat, pine cones for weapons, and beer cans worth money if you redeemed them. I ran to get out of the house. I ran because I was jumping out of my skin. I ran so I could be alone, running on restless legs that walked in and out of homerooms, kicking bullies in the schoolyard and slamming my brother in the shins. My sister just sat back and watched me fight, blinking bewildered black eyes and sucking contentedly on cookies. She could never figure out why I was so furious all the time. She was born with grace. Predictably, her Korean name, Young-Mi, means "flower." Mine is Young-Nan. It means "egg."

“Young Mi-ya!” my mother would call up the stairs to my baby sister. To me: “Young-Nanny! Young Nanneeeee! Wake up your sister! You’re late for school!”

“Not ‘Young Nanny’,” I’d glower, and pull my snoring sister out of bed. As I got her ready for school, my blissfully sleeping sister would drool lavishly on my hand-me-down shoes.

Having a crippled older religious man as your father means your parents start out gods with feet of clay, and they become mere mortals as soon as you’re on solid food. The emotional launch into adulthood starts long before biology catches up with you. By the time I was teenager, between convulsive bouts of school, I’d begun waddling around small continents in sensible shoes, carting around my precious packet of toilet paper, sunscreen, and a jar of antihistamines. Disappearing for months and years, I burrowed into cities such as Florence, London, and Seoul but mostly Paris, a place that bears remarkably little resemblance to the romantic fantasies spun about it. This was fine with me. I wasn’t looking for love, drugs, yoga classes or any other “girl” narratives attached to stories about free spirits bravely traveling alone. When your trips abroad are being paid for by your father/divorce settlement/publisher, you’re not free. You’re expensive. Besides which, I grew up foreign in a native country. From birth, you’re an alien being, a world traveler by default: dropped down the chimney by migratory storks.

In cities called Cosmopolitan, everyone is born of a bird. We are all the same kind, fine in our feathers but naked in our skins. Not all birds fly. Not all birds can.

There is no homing device in my head.

My mother prayed I’d run into a nice Korean boy and start making legally wedded babies. My father hoped my peregrinations would put me on the road to Damascus, where I’d see God’s truth and start preaching His word, writing letters to the Corinthians and voting Republican. I was St. Paul’s namesake, after all. My parents had been expecting a boy, because apparently I’d been one in the womb. That’s what the baby doctors told them. I chose to disagree. Given my conversion when I saw the light, my destiny was to become an apostle. Failing that, my father was thinking accountant. A good career choice for girls.

Ah, but in Latin, Paul also means “little,” which is what I ended up being. Or rather, very short. Sometimes wee, mostly Weeble. The wobble was incontestable.

I knew my mind, and it was strange. It disagreed with my body, and my body struggled to get away. Amazingly, wherever my body went, my brain went too, barking, “No meat for you!”