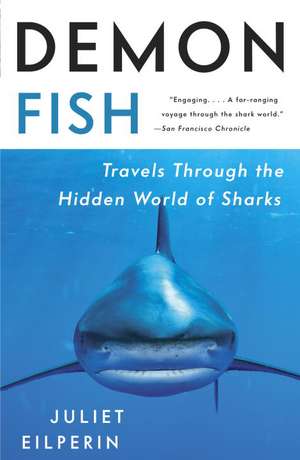

Demon Fish: Travels Through the Hidden World of Sharks

Autor Juliet Eilperinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2012

From Belize to South Africa, from Shanghai to Bimini, we see that sharks are still the object of an obsession that may eventually lead to their extinction. In this eye-opening adventure that spans the globe, environmental journalist Juliet Eilperin investigates the fascinating ways different individuals and cultures relate to the ocean's top predator. Along the way, she reminds us why, after millions of years, sharks remain among nature's most awe-inspiring creatures. With a reporter's instinct for a good story and a scientist's curiosity, Eilperin offers us an up-close understanding of these extraordinary, mysterious creatures in the most entertaining and illuminating shark encounter you're likely to find outside a steel cage.

Preț: 120.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 180

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.01€ • 24.03$ • 19.05£

23.01€ • 24.03$ • 19.05£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307386809

ISBN-10: 0307386805

Pagini: 295

Ilustrații: 8 PP. COLOR

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307386805

Pagini: 295

Ilustrații: 8 PP. COLOR

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Juliet Eilperin is the national environmental reporter for The Washington Post, where she writes about science, policy, and politics in areas ranging from climate change to oceans. A graduate of Princeton University, she lives with her family in Washington, D.C.

Extras

Each kind of auctioneer has a style. There’s the robust cattle auctioneer, who spits out numbers in a bold, singsong voice that determines where animals go to be bred or slaughtered; the elegant estate auctioneer, whose rich, mellifluous tone entices art and furniture collectors to fork over their savings; and then there’s Charlie Lim.

A spectacled, wiry man in his early fifties, Lim sports a short-sleeved, button-down shirt and a modified bowl cut that lets his straight black bangs fall neatly across his forehead. Standing in front of the sort of shiny whiteboards that appear in classrooms and corporate conference rooms across the globe, he doesn’t talk much as he auctions off his wares; instead, he shakes an abacus in short, regular bursts. Much of the time, the clicking of the beads is the loudest sound in the room.

Lim is a shark fin trader. More precisely, he’s the secretary of Hong Kong’s Sharkfin and Marine Products Association. And at the moment he’s standing in a nondescript auction house whose spare white decor evokes a Chelsea art gallery. But when the auction begins, the buyers crowd around Lim in a semicircle, jostling for a look at the gray triangular fi ns splayed across the floor. A shark fin auction is as fast as it is secretive. By the time Lim takes his position at the front of the room, one of his assistants has already marked on the board behind him—in a bright red felt-tipped pin—which sorts of fins are being auctioned in any given lot. As soon as men dump the contents of a burlap bag on the floor, the bidding begins: any interested buyer must approach Lim and punch his suggested price into a single device that only the auctioneer and his assistant can see. The bidders must make a calculated guess about what price will prevail, rather than compete with each other openly for a given bag of fins. Within two minutes the lot is sold, and the winning price per kilo is duly noted on the board. Lim’s assistants sweep the pile back into its bag, using a dustpan to gather any errant fins that might have escaped to the side. Another bag—containing the first dorsal, pectorals, and lower lobe of the caudal fins that are most valuable—is dumped on the floor, and the cycle begins again.

The group of men gathered here—and it’s all men—are experienced traders who hear about these auctions through word of mouth. There is no downtime, no chitchat; in fact, there aren’t even chairs for them to sit on during the auction. Given the quick pace of shark fin sales, they must be prepared to bid without hesitation. The bidders show no emotion during the entire process: this isn’t fine art they plan to furnish their homes with, or livestock they will devote months to raising. It is a heap of desiccated objects they will seek to transfer to someone else as soon as they acquire it.

Lim does make a few remarks in Cantonese about the fins before his feet, but it’s not the sort of chatter most auctioneers use to boost the price of a given lot. He’s not saying, “Take a look at these gray beauties!” or anything to that effect. Sometimes he indicates the species that’s collected in a given bag: blacktip, hammerhead, or blue shark. But a shark fin auction is not really about salesmanship. It’s about moving product.

Some rare metals and stones have carried a high market price for centuries. Basic foodstuffs, including several fish species, have also held a quantifiable commercial value over time. The shark trade, however, is a more recent arrival to the world scene. Unlike many other fish, such as salmon or red snapper, for example, shark does not derive its value from its taste or nutritional worth. In fact, there’s ample evidence that the high levels of toxins sharks accumulate in their bodies pose a potential threat to humans, just as tuna does. While many consumers—especially in China—view shark meat and fins as nutritious, sharks are likely to contain high levels of mercury because they are large, slow- growing fish that consume other fish as their prey, which allows mercury to build up in their muscle tissues. WildAid, an environmental group that crusades against shark fin trafficking, commissioned a study by the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research in 2001 that found shark fins in Bangkok’s markets contain mercury concentrations up to forty- two times above the safe limit for human health.

The market for sharks is based more on the animals’ mystique than anything else. In the same way that De Beers has convinced young men across the globe that women will be more likely to accept their marriage proposal if it comes with a diamond ring, men like Lim have managed to persuade Asian consumers that the very presence of stringy shark fin cartilage in their soup speaks to their own social status. Other marketers have different pitches, bottling sharks’ mysterious promise in a range of salves. One U.S. entrepreneur has made a decent amount of money peddling the line that sharks cure cancer, while other companies are in the business of advertising shark oil’s anti- aging properties. None of these appeals are based on science, but they tap into our long- held beliefs about the power of an animal that can consume us. And nowhere do they resonate more strongly than in Asia, where an ever-expanding group of consumers is seeking new ways to demonstrate its upwardly mobile status.

From the Hardcover edition.

A spectacled, wiry man in his early fifties, Lim sports a short-sleeved, button-down shirt and a modified bowl cut that lets his straight black bangs fall neatly across his forehead. Standing in front of the sort of shiny whiteboards that appear in classrooms and corporate conference rooms across the globe, he doesn’t talk much as he auctions off his wares; instead, he shakes an abacus in short, regular bursts. Much of the time, the clicking of the beads is the loudest sound in the room.

Lim is a shark fin trader. More precisely, he’s the secretary of Hong Kong’s Sharkfin and Marine Products Association. And at the moment he’s standing in a nondescript auction house whose spare white decor evokes a Chelsea art gallery. But when the auction begins, the buyers crowd around Lim in a semicircle, jostling for a look at the gray triangular fi ns splayed across the floor. A shark fin auction is as fast as it is secretive. By the time Lim takes his position at the front of the room, one of his assistants has already marked on the board behind him—in a bright red felt-tipped pin—which sorts of fins are being auctioned in any given lot. As soon as men dump the contents of a burlap bag on the floor, the bidding begins: any interested buyer must approach Lim and punch his suggested price into a single device that only the auctioneer and his assistant can see. The bidders must make a calculated guess about what price will prevail, rather than compete with each other openly for a given bag of fins. Within two minutes the lot is sold, and the winning price per kilo is duly noted on the board. Lim’s assistants sweep the pile back into its bag, using a dustpan to gather any errant fins that might have escaped to the side. Another bag—containing the first dorsal, pectorals, and lower lobe of the caudal fins that are most valuable—is dumped on the floor, and the cycle begins again.

The group of men gathered here—and it’s all men—are experienced traders who hear about these auctions through word of mouth. There is no downtime, no chitchat; in fact, there aren’t even chairs for them to sit on during the auction. Given the quick pace of shark fin sales, they must be prepared to bid without hesitation. The bidders show no emotion during the entire process: this isn’t fine art they plan to furnish their homes with, or livestock they will devote months to raising. It is a heap of desiccated objects they will seek to transfer to someone else as soon as they acquire it.

Lim does make a few remarks in Cantonese about the fins before his feet, but it’s not the sort of chatter most auctioneers use to boost the price of a given lot. He’s not saying, “Take a look at these gray beauties!” or anything to that effect. Sometimes he indicates the species that’s collected in a given bag: blacktip, hammerhead, or blue shark. But a shark fin auction is not really about salesmanship. It’s about moving product.

Some rare metals and stones have carried a high market price for centuries. Basic foodstuffs, including several fish species, have also held a quantifiable commercial value over time. The shark trade, however, is a more recent arrival to the world scene. Unlike many other fish, such as salmon or red snapper, for example, shark does not derive its value from its taste or nutritional worth. In fact, there’s ample evidence that the high levels of toxins sharks accumulate in their bodies pose a potential threat to humans, just as tuna does. While many consumers—especially in China—view shark meat and fins as nutritious, sharks are likely to contain high levels of mercury because they are large, slow- growing fish that consume other fish as their prey, which allows mercury to build up in their muscle tissues. WildAid, an environmental group that crusades against shark fin trafficking, commissioned a study by the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research in 2001 that found shark fins in Bangkok’s markets contain mercury concentrations up to forty- two times above the safe limit for human health.

The market for sharks is based more on the animals’ mystique than anything else. In the same way that De Beers has convinced young men across the globe that women will be more likely to accept their marriage proposal if it comes with a diamond ring, men like Lim have managed to persuade Asian consumers that the very presence of stringy shark fin cartilage in their soup speaks to their own social status. Other marketers have different pitches, bottling sharks’ mysterious promise in a range of salves. One U.S. entrepreneur has made a decent amount of money peddling the line that sharks cure cancer, while other companies are in the business of advertising shark oil’s anti- aging properties. None of these appeals are based on science, but they tap into our long- held beliefs about the power of an animal that can consume us. And nowhere do they resonate more strongly than in Asia, where an ever-expanding group of consumers is seeking new ways to demonstrate its upwardly mobile status.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Engaging. . . . A far-ranging voyage through the shark world.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“A compelling book: Its author not only knows all about her subject but she knows how readers think about it. . . . The main impression left by Demon Fish is that sharks are indeed all they are cracked up to be—and more.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Reveals the close relationship between humans and sharks through the interplay of history and culture. . . . By the end of Demon Fish, readers may be tempted to don a wet suit and go hug a shark.”

—The New York Times

“Eilperin circles the world in pursuit of sharks and the people who love and hate them. . . whether they are killers or protectors, she tells their stories with fairness and understanding. I forgot the time as I immersed myself in the world of sharks. . . . Whether you’ve never read a book about sharks or have a shelf full of them, this is a book for you.”

—Callum Roberts, The Washington Post

“Fascinating and meticulously reported book. . . . Eilperin illuminates not only the hidden nature of the seas, but also the societies whose survival depend on them.”

—David Grann, author of The Lost City of Z

“For this inclusive and important book, Eilperin traveled around the world to find people who study, fish for, dive with, venerate, or have been attacked by sharks. . . . [she] discusses many others who have brought sharks into human consciousness—Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe, Ernest Hemingway, and Jacques Cousteau; to this list, we must now add Eilperin herself.”

—Richard Ellis, The American Scholar

“Hate, fear, envy, awe, worship. Of the many shark books, precious few explore the human-shark relationship. And none do with such style as Juliet Eilperin does in this fact-packed, fast-paced narrative. This is the shark book for the person who wants to understand both what sharks are, and what sharks mean. Bite into it.”

—Carl Safina, author of Song for the Blue Ocean and The View From Lazy Point; A Natural Year in an Unnatural World

“Eilperin investigates the greatest threats to sharks: the shark fin trade and the ecological and economic forces affecting shark populations. . . The book is certainly timely. And Demon Fish does the subject justice.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Poised to be one of the summer’s most compelling beach reads.”

—NPR.org

“In this wide-ranging natural history of shark-human relations, the author recounts frank interviews with an entertaining cast of scientists, fishermen, wholesalers, chefs, and eco-tour operators, all of whom have a stake in the survival of the oceans’ top predators. She also gets into the water with the sharks. For readers who like passionate investigative reporting.”

—Booklist

—San Francisco Chronicle

“A compelling book: Its author not only knows all about her subject but she knows how readers think about it. . . . The main impression left by Demon Fish is that sharks are indeed all they are cracked up to be—and more.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Reveals the close relationship between humans and sharks through the interplay of history and culture. . . . By the end of Demon Fish, readers may be tempted to don a wet suit and go hug a shark.”

—The New York Times

“Eilperin circles the world in pursuit of sharks and the people who love and hate them. . . whether they are killers or protectors, she tells their stories with fairness and understanding. I forgot the time as I immersed myself in the world of sharks. . . . Whether you’ve never read a book about sharks or have a shelf full of them, this is a book for you.”

—Callum Roberts, The Washington Post

“Fascinating and meticulously reported book. . . . Eilperin illuminates not only the hidden nature of the seas, but also the societies whose survival depend on them.”

—David Grann, author of The Lost City of Z

“For this inclusive and important book, Eilperin traveled around the world to find people who study, fish for, dive with, venerate, or have been attacked by sharks. . . . [she] discusses many others who have brought sharks into human consciousness—Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe, Ernest Hemingway, and Jacques Cousteau; to this list, we must now add Eilperin herself.”

—Richard Ellis, The American Scholar

“Hate, fear, envy, awe, worship. Of the many shark books, precious few explore the human-shark relationship. And none do with such style as Juliet Eilperin does in this fact-packed, fast-paced narrative. This is the shark book for the person who wants to understand both what sharks are, and what sharks mean. Bite into it.”

—Carl Safina, author of Song for the Blue Ocean and The View From Lazy Point; A Natural Year in an Unnatural World

“Eilperin investigates the greatest threats to sharks: the shark fin trade and the ecological and economic forces affecting shark populations. . . The book is certainly timely. And Demon Fish does the subject justice.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Poised to be one of the summer’s most compelling beach reads.”

—NPR.org

“In this wide-ranging natural history of shark-human relations, the author recounts frank interviews with an entertaining cast of scientists, fishermen, wholesalers, chefs, and eco-tour operators, all of whom have a stake in the survival of the oceans’ top predators. She also gets into the water with the sharks. For readers who like passionate investigative reporting.”

—Booklist

Descriere

In this eye-opening adventure that spans the globe, Eilperin investigates the fascinating ways different individuals and cultures relate to sharks--the ocean's top predator. From Belize to South Africa, from Shanghai to Bimini, readers see why sharks are still the object of obsession.