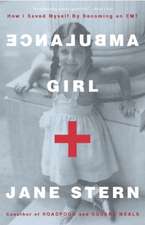

Descartes' Secret Notebook: A True Tale of Mathematics, Mysticism, and the Quest to Understand the Universe

Autor Amir D. Aczelen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

But Descartes had a mysterious and mystical side, as well. Almost certainly a member of the occult brotherhood of the Rosicrucians, he kept a secret notebook, now lost, most of which was written in code. After Descartes’s death, Gottfried Leibniz, inventor of calculus and one of the greatest mathematicians in history, moved to Paris in search of this notebook—and eventually found it in the possession of Claude Clerselier, a friend of Descartes. Leibniz called on Clerselier and was allowed to copy only a couple of pages—which, though written in code, he amazingly deciphered there on the spot. Leibniz’s hastily scribbled notes are all we have today of Descartes’s notebook, which has disappeared.

Why did Descartes keep a secret notebook, and what were its contents? The answers to these questions lead Amir Aczel and the reader on an exciting, swashbuckling journey, and offer a fascinating look at one of the great figures of Western culture.

Preț: 126.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 189

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.17€ • 26.26$ • 20.32£

24.17€ • 26.26$ • 20.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767920346

ISBN-10: 0767920341

Pagini: 273

Ilustrații: 30 LINEART AND HALFTONE INTERIOR ART PIECES

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767920341

Pagini: 273

Ilustrații: 30 LINEART AND HALFTONE INTERIOR ART PIECES

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

AMIR D. ACZEL is the author of many research articles on mathematics, two textbooks, and nine nonfiction books, including the international bestseller Fermat's Last Theorem, which was nominated for a Los Angeles Times Book Award. Aczel has appeared on over thirty television programs, including nationwide appearances on CNN, CNBC, and Nightline, and on over a hundred radio programs, including NPR's Weekend Edition and Morning Edition. Aczel is a Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

The Gardens of Touraine

JUST BEFORE RENE DESCARTES WAS born, on March 31, 1596, his mother, Jeanne Brochard, took an action that may well have altered the course of Western civilization. For like Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon in 49 B.C., Jeanne Brochard crossed the Creuse River, which lay between her family home, in the region of Poitou, and the small town of La Haye, which lies in the region of Touraine, in western central France.

The Descartes family had originated in Poitou and had lived for many years in the town of Chatellerault, about twenty-five kilometers south of La Haye. Descartes' parents, Joachim Descartes and Jeanne Brochard, who were married on January 15, 1589, owned a stately mansion in the center of Chatellerault, at 126 rue Carrou-Bernard (today's rue Bourbon).

Joachim Descartes was the councillor of the Parliament of Brittany, and this important job kept him away in distant Rennes. Jeanne needed her mother's help in birthing the baby, and this is why she traveled north and across the river to Touraine to give birth to René Descartes in her mother's house in La Haye. Sometime later, once she had recovered, she returned to Chatellerault. Despite this accident of birth, throughout his life, Rene's friends would often call him Rene le Poitevin--Rene of Poitou.

The regions of Poitou and Touraine include pastoral farmlands that have been cultivated since antiquity. There are low hills, many of which are forested, and rich flatlands, irrigated by rivers that cut through this fertile land. Cows and sheep graze here, and many kinds of crops are grown. La Haye is a small town of stone houses with gray roofs. At the time of Descartes, the population of the town numbered about 750 people.

Chatellerault is a larger, more genteel town than La Haye, with wide avenues and an elegant city square, and it serves as the hub of rural life in the region. Because this part of France is so fertile and rich in water and agricultural resources, the people who live here are well off. North of La Haye one can still visit the beautiful chateaus of the Loire Valley, as well as forests and game reserves, which existed at the time of Descartes. The chateaus, many of them restored to their original state, with lavish fifteenth- and sixteenth-century furnishings and surrounded by sculpted gardens, give us a feel for the life of the rich at the time of Descartes.

While the regions of Poitou and Touraine are similar in their topography, scenery, and the way the towns and villages are laid out, there was one important difference between them. While Poitou was mainly Protestant, Touraine was mostly Catholic. We know that in the fifteen years from 1576 to 1591, there were only seventy-two Protestant baptisms in La Haye. This significant religious difference between the two regions would affect the life of René Descartes. For this accident of birth--being born, and later also raised, in a strongly Catholic region while his family hailed from a Protestant one--would exert a significant impact on René's personality, thus influencing his actions throughout his life and determining the course of development of his philosophical and scientific ideas and the way he divulged them to the world.

Descartes lived in a century that knew severe tensions, including wars, between Catholics and Protestants. The fact that he was born in a Catholic region and would be raised by a devout Catholic governess, while many of his family's friends and associates in Poitou were Protestants, contributed to Descartes' natural secretiveness. It also made him, as an adult, much more concerned about the Catholic Inquisition than perhaps he should have been, and not worried enough about the persecution he could face from Protestants. Consequently, Descartes would refrain from publishing elements of his science and philosophy for fear of the Inquisition, and yet would readily settle in Protestant countries, where academics and theologians would viciously attack his work in part because they knew he was a Catholic.

René Descartes was baptized a Catholic in Saint George's Chapel in La Haye, a twelfth-century Norman church, on April 3, 1596. His baptismal certificate reads:

This day was baptized René, son of the noble man Joachym Descartes, councillor of the King and his Parliament of Brittany, and of damsel Jeanne Brochard. His godparents, noble Michel Ferrand, councillor of the King, lieutenant general of Chatellerault, and noble René Brochard, councillor of the King, judge magistrate at Poitiers, and dame Jeanne Proust, wife of monsieur Sain, controller of weights and measures for the King at Chatellerault.

[signed]

Ferrand Jehanne Proust Rene Brochard

Michel Ferrand, René Descartes' godfather, was his great-uncle--Joachim Descartes' uncle on his mother's side. Rene Brochard was the baby's grandfather, Jeanne Brochard's father. Jeanne's mother, René Descartes' grandmother, was Jeanne Sain. Her brother's wife was Jeanne (Jehanne) Proust.

***

The name La Haye comes from the French word haie, meaning hedge. Originally the town was named Haia, and in the eleventh century, as the language evolved, the spelling was changed to Haya. In Descartes' time it was called La Haye-en-Touraine. In 1802, the town's name was changed to La Haye-Descartes, in honor of the philosopher, and in 1967, "La Haye" was altogether dropped and the town is now known as Descartes.

There was once a castle in the area, and the wealthiest and most powerful citizens of La Haye lived in it. As the feudal system disintegrated, the castle was abandoned and the people moved down to the town, where they could live more comfortably. But life in this area remained difficult. People suffered both from wars and from disease. The plague ravaged La Haye and its surroundings several times in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In 1607, the town was placed under quarantine after a recurrence of the plague killed many people in the area.

In early times, the hedges denoted by the French name Haia (or Haya or Haie) stood for thorny hedges that were planted by the townspeople in an effort to defend themselves and their property from marauding bands of brigands and highwaymen that pillaged and looted the countryside. But as times improved after the duke of Anjou took control of the area in September 1596--six months after the birth of Rene Descartes--the hedges implied by the name of the town came to mean hedges of beautiful gardens. To this day, this part of France is known for its exquisite gardens and areas of great natural beauty.

Late in life, just before he left on his final journey to Stockholm, Descartes wrote to his dearest friend, Princess Elizabeth: "A man who was born in the gardens of Touraine, shouldn't he avoid going to live in the land of the bears, between rocks and ice?" Descartes may well have been thinking of the garden of his own childhood home, his grandmother's house in La Haye, when he wrote these words to Elizabeth. Descartes' childhood home is an attractive two-story country house with four large rooms, although it is not nearly as impressive as the family mansion in Chatellerault. But it is surrounded by an exuberant garden, now restored to its original state, with flowers under the generous canopy of graceful trees. One can imagine the young boy enjoying many hours of undisturbed thinking and playing in this tranquil garden.

***

A year after René was born, shortly after giving birth to her fourth child, Jeanne Brochard died. The newborn survived for three more days, and then died too. Some of Descartes' biographers have written that Rene's personality was deeply affected by the loss of his mother, and have even speculated that the young boy blamed himself for her death because he did not quite understand--the event having taken place so close to his own birth--that she died sometime after giving birth to her next child.

After the death of his wife, Joachim remarried. He took a Breton woman named Anne Morin as his wife, and with her had another son and another daughter (and two other babies who died in infancy). They bought a house in Rennes, where René's older sister joined them in 1610, and where she got married in 1613 to a local man. Until then, Rene and his older brother and sister were raised by a governess. Rene Descartes was extremely attached to his governess, who was a devout Catholic. She lived to old age, and Descartes specified in his will that she was to receive a significant amount of money annually for her support.

As a child, René became known as the young philosopher of the family because he had a great curiosity about the world, always wanting to know why things were the way they were. The child grew up in the natural environment of farming and hunting and strolling in the woods. Throughout his life he would make references to the bucolic land of his birth and its natural rhythms. In letters to friends, and in published works, he would describe his childhood memories: the smell of the earth after a rainstorm; the trees at different seasons of the year; the process of fermentation of hay, and the making of new wine; the churning of butter from fresh milk; and the feel of the dust rising up from the earth as it was being plowed. Perhaps it was this early closeness to nature that kindled his interest in physics and mathematics as means for understanding nature and unraveling her secrets.

The Descartes family was wealthy, and René would inherit even more assets directly from his grandfathers on both sides, both of whom had been successful medical doctors. His great-grandfather Jean Ferrand had been the personal physician of Queen Eleanor of Austria, the wife of Francis I of France, in the middle of the sixteenth century. He attained great wealth, which was eventually passed on to his daughter Claude, who married Pierre Descartes. Their son was Joachim Descartes, René's father. In 1566, when Joachim was only three years old, his father, Pierre, died of kidney stones. Pierre's father-in-law, Jean Ferrand, Queen Eleanor's personal physician, performed the autopsy on his son-in-law. In 1570 he wrote up the results of the operation and published them in a scientific paper, in Latin, about lithiasis--the formation of stony concretions in the body. His deep curiosity about nature--even to the point of dissecting the body of his own son-in-law--was passed on to his descendants. While, unlike his grandparents, René Descartes would not pursue medicine as a profession, late in life he would dissect many animals in search of the secret to eternal life.

***

René Descartes would spend much time during his adult life managing his inheritance. This wealth, including significant land holdings in Poitou, would enable him to pursue his interests without concern about a livelihood. It would afford him to indulge his whim of volunteering for military campaigns as a gentleman soldier without compensation--simply for the thrill of adventure. He would be able to afford luxurious accommodations wherever he traveled, and to employ servants and a valet. His money would even allow him to look after the education of his staff, thus sharing with them some of the privilege of his family's wealth. Descartes would grow up to be a very generous employer and friend.

Despite Adrien Baillet's statement in his very comprehensive 1691 biography of Descartes that the family belonged to the nobility, recent research indicates that, as far as Rene's life is concerned, this was not true. The renowned French historian Genevieve Rodis-Lewis explains in her 1995 biography, Descartes, that the Descartes family gained the rank of knighthood, the lowest status of nobility in France, only in 1668--eighteen years after René's death. According to French law, nobility was conferred on families after three successive generations had served the king in high office. Joachim Descartes certainly held such a position, and some have argued that he had originally sought to become councillor to the Parliament of Brittany in hopes of obtaining nobility status for his descendents. But Rene Descartes would choose a different direction in life, and so nobility would be conferred on the family only after another member had satisfied the three-generations requirement, years after René's death.

After he remarried, Joachim Descartes spent most of his time in Rennes with his new wife and the children she bore him. He also had interests and family business farther south and west in Nantes, also in Brittany. As they grew older, Rene and his brother and sister traveled frequently to visit their father. Eventually, Rene Descartes would see all of western France as his home territory, since time in his later childhood was spent throughout the regions of Poitou, Touraine, and Brittany.

But the frequent travel throughout the region was hard on the boy. In adulthood, Descartes described his health as a child as poor, and recounted in letters to friends that every doctor who had ever seen him as a child had said that he was in such poor health that he would most likely die at a young age. His devoted governess took such good care of him, however, that when he was eleven years old he was healthy enough to be sent away to study at the prestigious Jesuit College of La Flèche.

Chapter 2

Jesuit Mathematics and the Pleasures of the Capital

IN 1603, KING HENRY IV, WHO HAD been raised a Protestant but converted to Catholicism, gave the Jesuits, as a gesture of his goodwill toward this powerful Catholic order, his château and vast grounds in the town of La Flèche, to be used by them as the site of a new college. The Jesuits enlarged the chateau, and the result was a series of large interconnected Renaissance buildings with spacious, square, symmetric inner courtyards. Entering the grounds, one is struck by the perfect order and symmetry of the checkerboard array of grand courtyards, and by the well-manicured gardens beyond them. This is one of the most impressive college grounds anywhere; today it is the site of a military academy, the Prytanée National Militaire.

La Flèche was well chosen for a college. It lies in Anjou, north of Touraine, in a rich area with forests and gentle rolling hills. The town is attractive, with a river running through its center and lush meadows surrounding it. The gate of the college opens right into the spacious town square. Once students left the grounds of the college, they were in the center of the town with its many places to eat, drink, and find entertainment.

The college was inaugurated by King Henry IV, and opened its gates in 1604. France's brightest students from the best families were encouraged to apply for acceptance. Among the students accepted to the first class to enter this elite new college was Marin Mersenne (1588-1648), who would become Descartes' most devoted and loyal friend.

The college was run as a semimilitary school. The students had to wear a uniform, including breeches with pom-pom fastenings, a fancy blue blouse with large-puffed sleeves, and a felt hat. Each student was given a long list of items he had to bring to school. These included candles, various kinds of pencils, quills, and notebooks, and items of personal use.

The Gardens of Touraine

JUST BEFORE RENE DESCARTES WAS born, on March 31, 1596, his mother, Jeanne Brochard, took an action that may well have altered the course of Western civilization. For like Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon in 49 B.C., Jeanne Brochard crossed the Creuse River, which lay between her family home, in the region of Poitou, and the small town of La Haye, which lies in the region of Touraine, in western central France.

The Descartes family had originated in Poitou and had lived for many years in the town of Chatellerault, about twenty-five kilometers south of La Haye. Descartes' parents, Joachim Descartes and Jeanne Brochard, who were married on January 15, 1589, owned a stately mansion in the center of Chatellerault, at 126 rue Carrou-Bernard (today's rue Bourbon).

Joachim Descartes was the councillor of the Parliament of Brittany, and this important job kept him away in distant Rennes. Jeanne needed her mother's help in birthing the baby, and this is why she traveled north and across the river to Touraine to give birth to René Descartes in her mother's house in La Haye. Sometime later, once she had recovered, she returned to Chatellerault. Despite this accident of birth, throughout his life, Rene's friends would often call him Rene le Poitevin--Rene of Poitou.

The regions of Poitou and Touraine include pastoral farmlands that have been cultivated since antiquity. There are low hills, many of which are forested, and rich flatlands, irrigated by rivers that cut through this fertile land. Cows and sheep graze here, and many kinds of crops are grown. La Haye is a small town of stone houses with gray roofs. At the time of Descartes, the population of the town numbered about 750 people.

Chatellerault is a larger, more genteel town than La Haye, with wide avenues and an elegant city square, and it serves as the hub of rural life in the region. Because this part of France is so fertile and rich in water and agricultural resources, the people who live here are well off. North of La Haye one can still visit the beautiful chateaus of the Loire Valley, as well as forests and game reserves, which existed at the time of Descartes. The chateaus, many of them restored to their original state, with lavish fifteenth- and sixteenth-century furnishings and surrounded by sculpted gardens, give us a feel for the life of the rich at the time of Descartes.

While the regions of Poitou and Touraine are similar in their topography, scenery, and the way the towns and villages are laid out, there was one important difference between them. While Poitou was mainly Protestant, Touraine was mostly Catholic. We know that in the fifteen years from 1576 to 1591, there were only seventy-two Protestant baptisms in La Haye. This significant religious difference between the two regions would affect the life of René Descartes. For this accident of birth--being born, and later also raised, in a strongly Catholic region while his family hailed from a Protestant one--would exert a significant impact on René's personality, thus influencing his actions throughout his life and determining the course of development of his philosophical and scientific ideas and the way he divulged them to the world.

Descartes lived in a century that knew severe tensions, including wars, between Catholics and Protestants. The fact that he was born in a Catholic region and would be raised by a devout Catholic governess, while many of his family's friends and associates in Poitou were Protestants, contributed to Descartes' natural secretiveness. It also made him, as an adult, much more concerned about the Catholic Inquisition than perhaps he should have been, and not worried enough about the persecution he could face from Protestants. Consequently, Descartes would refrain from publishing elements of his science and philosophy for fear of the Inquisition, and yet would readily settle in Protestant countries, where academics and theologians would viciously attack his work in part because they knew he was a Catholic.

René Descartes was baptized a Catholic in Saint George's Chapel in La Haye, a twelfth-century Norman church, on April 3, 1596. His baptismal certificate reads:

This day was baptized René, son of the noble man Joachym Descartes, councillor of the King and his Parliament of Brittany, and of damsel Jeanne Brochard. His godparents, noble Michel Ferrand, councillor of the King, lieutenant general of Chatellerault, and noble René Brochard, councillor of the King, judge magistrate at Poitiers, and dame Jeanne Proust, wife of monsieur Sain, controller of weights and measures for the King at Chatellerault.

[signed]

Ferrand Jehanne Proust Rene Brochard

Michel Ferrand, René Descartes' godfather, was his great-uncle--Joachim Descartes' uncle on his mother's side. Rene Brochard was the baby's grandfather, Jeanne Brochard's father. Jeanne's mother, René Descartes' grandmother, was Jeanne Sain. Her brother's wife was Jeanne (Jehanne) Proust.

***

The name La Haye comes from the French word haie, meaning hedge. Originally the town was named Haia, and in the eleventh century, as the language evolved, the spelling was changed to Haya. In Descartes' time it was called La Haye-en-Touraine. In 1802, the town's name was changed to La Haye-Descartes, in honor of the philosopher, and in 1967, "La Haye" was altogether dropped and the town is now known as Descartes.

There was once a castle in the area, and the wealthiest and most powerful citizens of La Haye lived in it. As the feudal system disintegrated, the castle was abandoned and the people moved down to the town, where they could live more comfortably. But life in this area remained difficult. People suffered both from wars and from disease. The plague ravaged La Haye and its surroundings several times in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In 1607, the town was placed under quarantine after a recurrence of the plague killed many people in the area.

In early times, the hedges denoted by the French name Haia (or Haya or Haie) stood for thorny hedges that were planted by the townspeople in an effort to defend themselves and their property from marauding bands of brigands and highwaymen that pillaged and looted the countryside. But as times improved after the duke of Anjou took control of the area in September 1596--six months after the birth of Rene Descartes--the hedges implied by the name of the town came to mean hedges of beautiful gardens. To this day, this part of France is known for its exquisite gardens and areas of great natural beauty.

Late in life, just before he left on his final journey to Stockholm, Descartes wrote to his dearest friend, Princess Elizabeth: "A man who was born in the gardens of Touraine, shouldn't he avoid going to live in the land of the bears, between rocks and ice?" Descartes may well have been thinking of the garden of his own childhood home, his grandmother's house in La Haye, when he wrote these words to Elizabeth. Descartes' childhood home is an attractive two-story country house with four large rooms, although it is not nearly as impressive as the family mansion in Chatellerault. But it is surrounded by an exuberant garden, now restored to its original state, with flowers under the generous canopy of graceful trees. One can imagine the young boy enjoying many hours of undisturbed thinking and playing in this tranquil garden.

***

A year after René was born, shortly after giving birth to her fourth child, Jeanne Brochard died. The newborn survived for three more days, and then died too. Some of Descartes' biographers have written that Rene's personality was deeply affected by the loss of his mother, and have even speculated that the young boy blamed himself for her death because he did not quite understand--the event having taken place so close to his own birth--that she died sometime after giving birth to her next child.

After the death of his wife, Joachim remarried. He took a Breton woman named Anne Morin as his wife, and with her had another son and another daughter (and two other babies who died in infancy). They bought a house in Rennes, where René's older sister joined them in 1610, and where she got married in 1613 to a local man. Until then, Rene and his older brother and sister were raised by a governess. Rene Descartes was extremely attached to his governess, who was a devout Catholic. She lived to old age, and Descartes specified in his will that she was to receive a significant amount of money annually for her support.

As a child, René became known as the young philosopher of the family because he had a great curiosity about the world, always wanting to know why things were the way they were. The child grew up in the natural environment of farming and hunting and strolling in the woods. Throughout his life he would make references to the bucolic land of his birth and its natural rhythms. In letters to friends, and in published works, he would describe his childhood memories: the smell of the earth after a rainstorm; the trees at different seasons of the year; the process of fermentation of hay, and the making of new wine; the churning of butter from fresh milk; and the feel of the dust rising up from the earth as it was being plowed. Perhaps it was this early closeness to nature that kindled his interest in physics and mathematics as means for understanding nature and unraveling her secrets.

The Descartes family was wealthy, and René would inherit even more assets directly from his grandfathers on both sides, both of whom had been successful medical doctors. His great-grandfather Jean Ferrand had been the personal physician of Queen Eleanor of Austria, the wife of Francis I of France, in the middle of the sixteenth century. He attained great wealth, which was eventually passed on to his daughter Claude, who married Pierre Descartes. Their son was Joachim Descartes, René's father. In 1566, when Joachim was only three years old, his father, Pierre, died of kidney stones. Pierre's father-in-law, Jean Ferrand, Queen Eleanor's personal physician, performed the autopsy on his son-in-law. In 1570 he wrote up the results of the operation and published them in a scientific paper, in Latin, about lithiasis--the formation of stony concretions in the body. His deep curiosity about nature--even to the point of dissecting the body of his own son-in-law--was passed on to his descendants. While, unlike his grandparents, René Descartes would not pursue medicine as a profession, late in life he would dissect many animals in search of the secret to eternal life.

***

René Descartes would spend much time during his adult life managing his inheritance. This wealth, including significant land holdings in Poitou, would enable him to pursue his interests without concern about a livelihood. It would afford him to indulge his whim of volunteering for military campaigns as a gentleman soldier without compensation--simply for the thrill of adventure. He would be able to afford luxurious accommodations wherever he traveled, and to employ servants and a valet. His money would even allow him to look after the education of his staff, thus sharing with them some of the privilege of his family's wealth. Descartes would grow up to be a very generous employer and friend.

Despite Adrien Baillet's statement in his very comprehensive 1691 biography of Descartes that the family belonged to the nobility, recent research indicates that, as far as Rene's life is concerned, this was not true. The renowned French historian Genevieve Rodis-Lewis explains in her 1995 biography, Descartes, that the Descartes family gained the rank of knighthood, the lowest status of nobility in France, only in 1668--eighteen years after René's death. According to French law, nobility was conferred on families after three successive generations had served the king in high office. Joachim Descartes certainly held such a position, and some have argued that he had originally sought to become councillor to the Parliament of Brittany in hopes of obtaining nobility status for his descendents. But Rene Descartes would choose a different direction in life, and so nobility would be conferred on the family only after another member had satisfied the three-generations requirement, years after René's death.

After he remarried, Joachim Descartes spent most of his time in Rennes with his new wife and the children she bore him. He also had interests and family business farther south and west in Nantes, also in Brittany. As they grew older, Rene and his brother and sister traveled frequently to visit their father. Eventually, Rene Descartes would see all of western France as his home territory, since time in his later childhood was spent throughout the regions of Poitou, Touraine, and Brittany.

But the frequent travel throughout the region was hard on the boy. In adulthood, Descartes described his health as a child as poor, and recounted in letters to friends that every doctor who had ever seen him as a child had said that he was in such poor health that he would most likely die at a young age. His devoted governess took such good care of him, however, that when he was eleven years old he was healthy enough to be sent away to study at the prestigious Jesuit College of La Flèche.

Chapter 2

Jesuit Mathematics and the Pleasures of the Capital

IN 1603, KING HENRY IV, WHO HAD been raised a Protestant but converted to Catholicism, gave the Jesuits, as a gesture of his goodwill toward this powerful Catholic order, his château and vast grounds in the town of La Flèche, to be used by them as the site of a new college. The Jesuits enlarged the chateau, and the result was a series of large interconnected Renaissance buildings with spacious, square, symmetric inner courtyards. Entering the grounds, one is struck by the perfect order and symmetry of the checkerboard array of grand courtyards, and by the well-manicured gardens beyond them. This is one of the most impressive college grounds anywhere; today it is the site of a military academy, the Prytanée National Militaire.

La Flèche was well chosen for a college. It lies in Anjou, north of Touraine, in a rich area with forests and gentle rolling hills. The town is attractive, with a river running through its center and lush meadows surrounding it. The gate of the college opens right into the spacious town square. Once students left the grounds of the college, they were in the center of the town with its many places to eat, drink, and find entertainment.

The college was inaugurated by King Henry IV, and opened its gates in 1604. France's brightest students from the best families were encouraged to apply for acceptance. Among the students accepted to the first class to enter this elite new college was Marin Mersenne (1588-1648), who would become Descartes' most devoted and loyal friend.

The college was run as a semimilitary school. The students had to wear a uniform, including breeches with pom-pom fastenings, a fancy blue blouse with large-puffed sleeves, and a felt hat. Each student was given a long list of items he had to bring to school. These included candles, various kinds of pencils, quills, and notebooks, and items of personal use.

Recenzii

“Aczel catapults the reader into a world where burgeoning intellect was cloaked in intrigue.” —The Washington Post Book World

“Aczel joins the ranks of Roger Penrose, Stephen Pinker, Francis Crick, and others.”—Keith Devlin, author of Goodbye, Descartes: The End of Logic and the Search for a New Cosmology of the Mind

“Splendid . . . first-rate.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Aczel reveals the mystery behind . . . one of the Western world’s greatest minds . . . [Descartes’s Secret Notebook] reads like a mystery novel as well as a biography.” —Science News

“Aczel joins the ranks of Roger Penrose, Stephen Pinker, Francis Crick, and others.”—Keith Devlin, author of Goodbye, Descartes: The End of Logic and the Search for a New Cosmology of the Mind

“Splendid . . . first-rate.” —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Aczel reveals the mystery behind . . . one of the Western world’s greatest minds . . . [Descartes’s Secret Notebook] reads like a mystery novel as well as a biography.” —Science News

Descriere

A towering figure in Western philosophy and mathematics, Descartes had a mysterious and mystical side, as well. Almost certainly a member of the occult brotherhood of the Rosicrucians, he kept a secret, coded notebook. What does the notebook reveal?