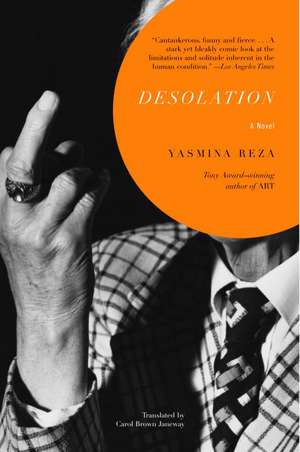

Desolation

Autor Yasmina Reza Traducere de Carol Janewayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2003

Whether he is recounting his pal Lionel’s heroic battle against impotence; lamenting the loss of his great love, the irresistible Marisa Botton; or pondering the possibility of a new love in the person of one Genevieve Abramowitz, the droll, irascible Perlman is one of the great talkers of contemporary fiction. And Desolation is one of the most dazzling performances ever written for one voice.

Preț: 59.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 89

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.32€ • 11.85$ • 9.43£

11.32€ • 11.85$ • 9.43£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375724725

ISBN-10: 0375724729

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 126 x 209 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375724729

Pagini: 144

Dimensiuni: 126 x 209 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Yasmina Reza is a playwright and novelist whose plays have all been multi-award-winning critical and popular international successes, translated in more than thirty languages. Her plays include Conversations After a Burial, The Passage of Winter, Art (which was awarded a Tony in 1999), The Unexpected Man, and Life ? 3. She is also the author of a translation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, a novel, Hammerklavier, and a film, Lulu Kreutz’s Picnic. She lives in Paris.

Extras

The garden–all me.

The word is, you have a good gardener. People say to me, You have a good gardener! What gardener?! A laborer, a workman. He carries things out. You, you do the thinking. Him, he pushes the wheelbarrow and he carries things out. Everything–I've done everything in the garden. People congratulate Nancy on the flowers. I decide on the color scheme and the plants, I site them, I buy the seeds, I buy the bulbs, and her, what does she do?–it gives her an activity, you'll tell me–she plants them. People congratulate her. That's life. The celebration of the superfluous.

I'd like you to explain the word happy.–

On Sundays I talk about you with your sister, because I talk about you. You, you think I don't talk about you, but I do talk about you. She tells me, He's happy.

Happy? The other day, at Ren? Fortuny's, some idiot said, "Surely the purpose of life is to be happy." On the way home in the car I said to Nancy, "Did you ever hear anything so banal?" To which Nancy's sub- tle response was, "So what should it be, according to you?" For her, happiness is legitimate, you know. She's one of those people who think happiness is legitimate.

Do you know her latest accusation? I had a new roller blind made for the laundry room. You know how much the guy wanted to charge me to install the Japanese shade I could buy readymade in any supermarket? Two hundred twenty dollars. I object. I'm not looking to get robbed, you know. Finally, the guy, who's a robber, knocks off $40. You know what upsets her? That I spent a hour and a half getting him down $40. Her argument? You reckon you're worth $40 an hour. Trying to make me mad. And her other argument? The guy has to earn a living. That's how she is.

So you're happy. At least that's what they say.

People say you're idle, people say you're nonproductive, and then they say, He's happy. I've fathered someone happy.

I, who strive to achieve some modest contentment in the middle of this pleasant flowerbed, I spawned a happy man. I, who was accused, principally by your mother, of tyranny, most especially with regard to you, accused of excessive severity, of injustice three times out of five, I stand here today in contemplation of the good–the excellent–results of my educational efforts. Granted, I didn't foresee the hatching of a contemplative being, but isn't a father's desire the happiness of his family?

Happy, your sister says. He's thirty-eight, and he crisscrosses the world on the 99 cents he gets from subletting the apartment I rent for him.

Crisscrosses the world. Let's face it. . . .

I say, "What does he do? In the morning he steps out of the bungalow. He looks at the sea. It's beautiful. Okay, I agree, it's beautiful. He looks at the sea. Fine. It's twelve minutes past seven. He steps back into the bungalow, and eats a papaya. He goes out again. It's still beautiful. Thirteen minutes past eight . . . and then?"

What happens then? That's when you have to start telling me what happy means.

You're looking well. Good weather in Mombasa. Mombasa or Kuala Lumpur, I don't give a shit, don't let's get bogged down in details. It's all the same to me. After thirteen minutes past eight, East or West, the world is you.

Hats off, my boy, one generation and you've wiped out the only credo by which I've lived. I, whose only terror is the daily monotony, who would swing open the gates of Hell to escape that mortal enemy, I have a son who samples exotic fruits with the savages. Truth has many faces, your sister said to me in an upsurge of idiocy. Indeed. But truth in the guise of a papaya-sucker is opaque, you know.

It would be hopeless trying to find the slightest trace of impatience or restlessness in you, you sleep, I imagine, you sleep like a log, you don't belong to the band of wanderers who pace the predawn streets and are my friends, it would be hopeless trying to find a hint of futile anxieties, inchoate restlessness, in a word–unease. I'm not even sure you understand why I'm concerned about you. That I can worry about your lack of worry must strike you as a new phase of my monomania, no? You wonder why I don't relax, you say to yourself, What does he do with his days, in a state of perpetual metamorphosis, what's the sense of it, never sated, never appeased. Appeased! Don't know the word. My son, any man who has tasted action dreads fulfillment, because there's nothing sadder or more washed out than the accomplished act. If I weren't in a constant state of metamorphosis, I'd have to battle the gloom that comes with endings because I refuse to wind down in some female fit of the vapors. At your age I knew about conquest, but more important, I already knew about loss. For you see I have never had any desire to conquer things in order to keep them. Nor to be some particular person just to stay that way. Quite the opposite. As soon as I settled on a self, I had to undo that self again. Only be whoever you're going to be next, my boy. Your only satisfaction lies in hope. And now my offspring opts to be becalmed in a slack prosperity based on utter lack of ambition and wandering all four points of the compass. Basically, if I've never dared to attack happiness, and I mean attack, please note, as in assault a fortress, you don't conquer a fortress by lying in the sun eating papayas, if I've never attacked happiness, I say, it's maybe because it's the only state you cannot fall out of without hurting yourself. It's a glancing blow but you never heal. You, poor sweetheart, you want peace right away. Peace! When it comes to vocabulary, let me do the honors. To be precise, it's well-being. You want to turn into a piece of seaweed as fast as you can. You're not even trying to fake some spiritual infatuation, I could be taken in by that, I'm not un-naÌøve. No. You come back tanned, calm, smiling, you sent two or three anodyne postcards and people who want to please me–want to please me!–say, He's happy.

When you were a child, you groveled at my feet for months because you wanted a dog. Do you remember? For months you groveled, you cried, you begged, you asked over and over again. I said no, categorically, you kept on nagging. One day you uttered the word hamster.

You had swapped the dog for a rat. I said no to the hamster and earned myself the right to hear the word fish. You couldn't sink any lower.

Your mother persuaded me to agree to fish, and we had the aquarium.

Were you happy with the aquarium? I pitied you, my boy.

* * *

You see these primulas, sluts, they're choking the leeks, nobody thinks of doing any weeding. If I don't take care of it, with my back that's killing me, nobody will. You have to be nice to the maids, according to Nancy. Nice means not asking them to do anything. Recently she said, If Mrs. Dacimiento quits, I quit too. Under the pretext that I wasn't being sufficiently nice to Mrs. Dacimiento. Whatever Mrs. Dacimiento's faults or qualities–of which she has fewer and fewer–I am supposed to curb myself because she is a servant. So what if Mrs. Dacimiento is now mediocrity-made-flesh, someone who can neither climb stairs nor bend over, Mrs. Dacimiento can't even raise her eyes or lower them, she can only see the world at her own level. She's married to a man who installs central heating, a stay-at-home who hates everything. Doesn't even like football on TV. Which is weird for a Portuguese. The Portuguese like big balls, fat, and car catalogs. Hers likes nothing.

From the Hardcover edition.

The word is, you have a good gardener. People say to me, You have a good gardener! What gardener?! A laborer, a workman. He carries things out. You, you do the thinking. Him, he pushes the wheelbarrow and he carries things out. Everything–I've done everything in the garden. People congratulate Nancy on the flowers. I decide on the color scheme and the plants, I site them, I buy the seeds, I buy the bulbs, and her, what does she do?–it gives her an activity, you'll tell me–she plants them. People congratulate her. That's life. The celebration of the superfluous.

I'd like you to explain the word happy.–

On Sundays I talk about you with your sister, because I talk about you. You, you think I don't talk about you, but I do talk about you. She tells me, He's happy.

Happy? The other day, at Ren? Fortuny's, some idiot said, "Surely the purpose of life is to be happy." On the way home in the car I said to Nancy, "Did you ever hear anything so banal?" To which Nancy's sub- tle response was, "So what should it be, according to you?" For her, happiness is legitimate, you know. She's one of those people who think happiness is legitimate.

Do you know her latest accusation? I had a new roller blind made for the laundry room. You know how much the guy wanted to charge me to install the Japanese shade I could buy readymade in any supermarket? Two hundred twenty dollars. I object. I'm not looking to get robbed, you know. Finally, the guy, who's a robber, knocks off $40. You know what upsets her? That I spent a hour and a half getting him down $40. Her argument? You reckon you're worth $40 an hour. Trying to make me mad. And her other argument? The guy has to earn a living. That's how she is.

So you're happy. At least that's what they say.

People say you're idle, people say you're nonproductive, and then they say, He's happy. I've fathered someone happy.

I, who strive to achieve some modest contentment in the middle of this pleasant flowerbed, I spawned a happy man. I, who was accused, principally by your mother, of tyranny, most especially with regard to you, accused of excessive severity, of injustice three times out of five, I stand here today in contemplation of the good–the excellent–results of my educational efforts. Granted, I didn't foresee the hatching of a contemplative being, but isn't a father's desire the happiness of his family?

Happy, your sister says. He's thirty-eight, and he crisscrosses the world on the 99 cents he gets from subletting the apartment I rent for him.

Crisscrosses the world. Let's face it. . . .

I say, "What does he do? In the morning he steps out of the bungalow. He looks at the sea. It's beautiful. Okay, I agree, it's beautiful. He looks at the sea. Fine. It's twelve minutes past seven. He steps back into the bungalow, and eats a papaya. He goes out again. It's still beautiful. Thirteen minutes past eight . . . and then?"

What happens then? That's when you have to start telling me what happy means.

You're looking well. Good weather in Mombasa. Mombasa or Kuala Lumpur, I don't give a shit, don't let's get bogged down in details. It's all the same to me. After thirteen minutes past eight, East or West, the world is you.

Hats off, my boy, one generation and you've wiped out the only credo by which I've lived. I, whose only terror is the daily monotony, who would swing open the gates of Hell to escape that mortal enemy, I have a son who samples exotic fruits with the savages. Truth has many faces, your sister said to me in an upsurge of idiocy. Indeed. But truth in the guise of a papaya-sucker is opaque, you know.

It would be hopeless trying to find the slightest trace of impatience or restlessness in you, you sleep, I imagine, you sleep like a log, you don't belong to the band of wanderers who pace the predawn streets and are my friends, it would be hopeless trying to find a hint of futile anxieties, inchoate restlessness, in a word–unease. I'm not even sure you understand why I'm concerned about you. That I can worry about your lack of worry must strike you as a new phase of my monomania, no? You wonder why I don't relax, you say to yourself, What does he do with his days, in a state of perpetual metamorphosis, what's the sense of it, never sated, never appeased. Appeased! Don't know the word. My son, any man who has tasted action dreads fulfillment, because there's nothing sadder or more washed out than the accomplished act. If I weren't in a constant state of metamorphosis, I'd have to battle the gloom that comes with endings because I refuse to wind down in some female fit of the vapors. At your age I knew about conquest, but more important, I already knew about loss. For you see I have never had any desire to conquer things in order to keep them. Nor to be some particular person just to stay that way. Quite the opposite. As soon as I settled on a self, I had to undo that self again. Only be whoever you're going to be next, my boy. Your only satisfaction lies in hope. And now my offspring opts to be becalmed in a slack prosperity based on utter lack of ambition and wandering all four points of the compass. Basically, if I've never dared to attack happiness, and I mean attack, please note, as in assault a fortress, you don't conquer a fortress by lying in the sun eating papayas, if I've never attacked happiness, I say, it's maybe because it's the only state you cannot fall out of without hurting yourself. It's a glancing blow but you never heal. You, poor sweetheart, you want peace right away. Peace! When it comes to vocabulary, let me do the honors. To be precise, it's well-being. You want to turn into a piece of seaweed as fast as you can. You're not even trying to fake some spiritual infatuation, I could be taken in by that, I'm not un-naÌøve. No. You come back tanned, calm, smiling, you sent two or three anodyne postcards and people who want to please me–want to please me!–say, He's happy.

When you were a child, you groveled at my feet for months because you wanted a dog. Do you remember? For months you groveled, you cried, you begged, you asked over and over again. I said no, categorically, you kept on nagging. One day you uttered the word hamster.

You had swapped the dog for a rat. I said no to the hamster and earned myself the right to hear the word fish. You couldn't sink any lower.

Your mother persuaded me to agree to fish, and we had the aquarium.

Were you happy with the aquarium? I pitied you, my boy.

* * *

You see these primulas, sluts, they're choking the leeks, nobody thinks of doing any weeding. If I don't take care of it, with my back that's killing me, nobody will. You have to be nice to the maids, according to Nancy. Nice means not asking them to do anything. Recently she said, If Mrs. Dacimiento quits, I quit too. Under the pretext that I wasn't being sufficiently nice to Mrs. Dacimiento. Whatever Mrs. Dacimiento's faults or qualities–of which she has fewer and fewer–I am supposed to curb myself because she is a servant. So what if Mrs. Dacimiento is now mediocrity-made-flesh, someone who can neither climb stairs nor bend over, Mrs. Dacimiento can't even raise her eyes or lower them, she can only see the world at her own level. She's married to a man who installs central heating, a stay-at-home who hates everything. Doesn't even like football on TV. Which is weird for a Portuguese. The Portuguese like big balls, fat, and car catalogs. Hers likes nothing.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Cantankerous, funny and fierce . . . . a stark yet bleakly comic look at the limitations and solitude inherent in the human condition.” –Los Angeles Times

“Darkly comic. . . . . Reza . . . has conjured a character who, seen through the keen lens of her gimlet eye, is equal parts monster and mensch.” – Elle

“Devilishly well-composed, hilarious, yet venomous….Smart and delectable…covers a gratifying range of emotions and provocative moral, spiritual and cultural terrain with sensitivity and virtuosity.” – Booklist

“[Reza] has an easy understanding of just how amusing men can be when free-floating anxiety and frustration overwhelm them.”—The New York Times

“Darkly comic. . . . . Reza . . . has conjured a character who, seen through the keen lens of her gimlet eye, is equal parts monster and mensch.” – Elle

“Devilishly well-composed, hilarious, yet venomous….Smart and delectable…covers a gratifying range of emotions and provocative moral, spiritual and cultural terrain with sensitivity and virtuosity.” – Booklist

“[Reza] has an easy understanding of just how amusing men can be when free-floating anxiety and frustration overwhelm them.”—The New York Times