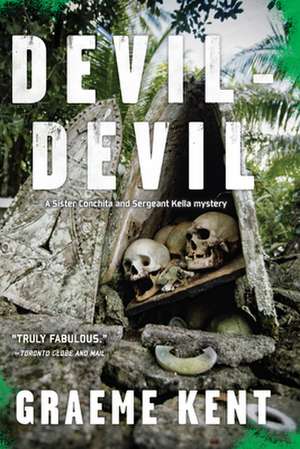

Devil-Devil

Autor Graeme Kenten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2012

the past few days he has been cursed by a magic man, stumbled across evidence of a cargo cult uprising, and failed to find an American anthropologist who had been scouring the mountains for a priceless pornographic icon. Then, at a mission station, Kella discovers an independent and rebellious young American nun, Sister Conchita, secretly trying to bury a skeleton. The unlikely pair of Kella and Conchita are forced to team up to solve a series of murders that tie into all these other strange goings-on. Set in the 60's in one of the most beautiful and dangerous areas of the South Pacific, Devil-Devil launches an exciting new series.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 90.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.32€ • 18.82$ • 14.56£

17.32€ • 18.82$ • 14.56£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781616950606

ISBN-10: 1616950609

Pagini: 281

Dimensiuni: 129 x 189 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

ISBN-10: 1616950609

Pagini: 281

Dimensiuni: 129 x 189 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Soho Crime

Notă biografică

For eight years, Graeme Kent was Head of BBC Schools broadcasting in the Solomon Islands. Prior to that he taught in six primary schools in the UK and was headmaster of one. Currently, he is Educational Broadcasting Consultant for the South Pacific Commission.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

THE GLORY SHELL

Sister Conchita clung to the sides of the small dugout canoe as

the waves pounded over the frail vessel, soaking its two

occupants. In front of her the Malaitan scooped his paddle into

the water, trying to keep the craft on an even balance. Sister

Conchita could see the coastal village a hundred yards away. The

beach was crowded with islanders. She wondered whether it had

been worth the perilous sea journey just to see the shark-calling

ceremony when all she wanted was a shower and a meal. Of

course it was, she told herself severely. If she intended serving

God in the Solomons then she had to get to know everything

about the islands.

The half-naked islander in front of her suddenly gave a scream

of terror. Turning, he thrust the paddle into the sister’s hands and

dived over the side of the canoe, disappearing into the frothing

white foam. Sister Conchita sat rigid with apprehension, the

pitted wooden blade clutched loosely in her hands. Bereft of

the islander’s control, the canoe started pitching and swinging

wildly.

For a moment all that Sister Conchita wanted to do was to

cower helplessly in the bucking wooden frame. Then her

customary resourcefulness took over. Snap out of it, she thought

grimly. You got yourself into this hole, better get out of it the

1

same way, girl. Muttering a fervent prayer, she tightened her

grip on the paddle and thrust it with all her force into the water.

For the next five minutes the wiry young sister fought the sea.

The momentum of the current was sending her at breakneck

speed in the direction of the beach and the watching islanders,

but the waves were crashing over the canoe at an angle, buffeting

it from side to side. Several times the entire tree shell was

submerged beneath the surface, but on each occasion it surfaced

sufficiently for the sodden nun, coughing and gasping, to resume

her paddling.

Doggedly she kept the prow of the canoe pointing at the

beach. After an apparent eternity of choking, muscle-aching

effort the shore actually seemed to be getting closer. One final

shock of a wave descended on the canoe and hurled it sprawling

up into the shallows off the beach.

Half a dozen brawny, cheering Melanesian men in skimpy

loincloths splashed into the water and laughingly hauled the

canoe up on to the sand. The crowd of assembled islanders broke

into delighted applause. Dazedly Sister Conchita stood up and

limped out of the beached craft.

Gradually her vision cleared. She blinked hard. Standing in

front of her, joining vigorously in the acclamation among the

large crowd, was the islander who had discarded his paddle and

left her to fight the sea alone. Struggling for breath, Sister

Conchita fought for the words adequately to express her opinion

of him.

‘They’ve just been pulling your leg, sister,’ drawled a

contemptuous voice from behind her. ‘They wanted to see what

you were made of. You didn’t do so bad. Most sheilas just stay

in the boat screaming bloody murder.’

The nun turned to see John Deacon, unshaven and clad in

khaki shorts and shirt, regarding her coolly from the edge of the

crowd.

GRAEME KENT

2

‘Mr Deacon,’ said Sister Conchita, trying to keep her balance.

Deacon was an Australian who managed a local copra plantation.

She did not like him, suspecting him of ill-treating his labourers.

However, she always tried, she suspected in vain, to conceal her

feelings.

‘Local custom,’ explained the stocky, broad-shouldered Australian

laconically. ‘Any stranger approaching the beach, the

guide jumps overboard. Actually the current is bound to bring

the canoe up on to the shore, but if you don’t know that, it can

be a mite disconcerting.’

‘You can say that again,’ said Sister Conchita.

‘At least you had a go,’ acknowledged the plantation manager.

‘The natives like guts.’

‘Have you come for the ceremony?’ asked Sister Conchita

politely, trying to change the subject. She did not wish to be

reminded too much of her undignified arrival.

The Australian snorted with derision. ‘I don’t believe in

superstition,’ he told her. His eyes scanned her tattered, oncewhite

habit. ‘Any superstition,’ he told her with emphasis. ‘I’m

here to pick up a cargo.’

Suddenly Deacon was swept aside by a phalanx of island

women, offering the nun rough blankets with which to dry

herself, together with a husk of coconut milk. In a chattering

group they conducted her to a site at the water’s edge and waited

eagerly with her. An artificial lagoon about twenty yards in

diameter had been constructed there with piles of stones marking

its edges, and an aperture on the seaward side to allow fish to

swim in and out.

As the nun watched, an old man in tattered shorts and singlet

emerged from one of the huts and walked down towards the

stones. A profusion of ancient bone charms rattled on a string

around his neck. A naked small boy of about ten years of age

accompanied him.

DEVIL-DEVIL

3

‘Fa’atabu,’ muttered an awed woman. She translated for the

nun’s benefit. ‘This one is the shark-caller,’ she said, indicating

the old man.

Four islanders splashed out into the shallow waters of the shark

area. They were carrying large flat stones, which they banged

together under the water. Simultaneously the shark-caller started

chanting in a high, tuneless voice. The crowd, which had swollen

in numbers to several hundred, looked on in expectant silence.

For several minutes nothing happened. Then a reverent

murmur went round the crowd. The fins of half a dozen sharks

could be seen entering the enclosure.

The men, still clashing the stones together, fled from the

water. Women picked up a few baskets of raw pork and placed

them at the water’s edge before withdrawing hastily. Completely

unperturbed, the boy hoisted one of the baskets up on to his

shoulder and staggered out with it into the water, to a depth of

several feet. To the accompaniment of screams and shouts from

the crowd on the shore the sharks began to swim steadily towards

the boy.

Sister Conchita found herself clenching her fists at the sight.

The boy stood still for a moment. Then he reached up into the

basket and started feeding the sharks lumps of raw meat,

dropping these into the water just in front of him. As the sharks

approached, accepting the food, the boy began to caress them.

Throughout, the shark-caller continued his keening.

Sister Conchita looked on, fascinated by the sight. Out of the

corner of her eye she became aware of Deacon and two

Melanesians carrying a bulky sack along the ramshackle wooden

jetty protruding into the sea. A dinghy was tethered there,

bobbing in the water. Farther out to sea she could see the

Australian’s trading vessel at anchor.

The sister did not want to leave the ceremony but she thought

that it would only be courteous to say goodbye to the brusque

GRAEME KENT

4

plantation manager. Reluctantly she slipped through the crowd

and made her way along the wharf. Deacon and his helpers were

trying to load the sack into the heaving dinghy. The islanders

were struggling to lower the sack to Deacon, waiting impatiently

below. As she approached, one of the Melanesians dropped his

end of the bulging sack. It burst open, disgorging a cascade of

seashells.

Sister Conchita increased her pace to see if she could help.

Some of the shells rolled across the wooden platform and nestled

at her feet. The nun stooped to pick them up.

‘Leave that; we’ll sort it!’ ordered Deacon, scrambling up from

the dinghy.

Sister Conchita ignored him. She had cradled three shells in

her hands and was examining them with increasing excitement

and anxiety. She would have recognized them anywhere. Before

she had left Chicago she had attended a museum display of South

Pacific seashells. The ones in her hands were a delicate golden

brown in colour, with a round base tapering exquisitely to a

point.

‘Are you deaf? I said I’ll take those!’ shouted Deacon,

lumbering towards her.

Sister Conchita was intimidated by the Australian’s looming

presence but stubbornly she clutched the beautiful shells to her.

‘I think not, Mr Deacon,’ she said, refusing to take a pace

backwards, although every instinct warned her to get away from

the plantation manager. ‘I believe these are glory shells,’ she went

on. ‘You have no right to be taking them off the island. They’re

a part of the culture of the Solomons.’

The Conus gloriamaris, or Glory of the Seas, was the rarest of

all seashells to be found in the Solomons, sought after in vain by

almost every islander. It fetched over a thousand dollars among

collectors. Its export was expressly forbidden by the government.

‘Mind your own business!’ grunted Deacon. ‘Or . . .’

DEVIL-DEVIL

5

‘Or what, Mr Deacon?’ asked Sister Conchita, still standing

her ground, although she was conscious that she was trembling.

It had been a long time since she had been exposed to an

example of such apparently uncontrollable wrath.With relief she

realized that a group of village men, attracted by the altercation

between the two expatriates, had abandoned the shark-calling

ceremony temporarily and were hurrying along the jetty behind

them.

‘This is a Catholic village, Mr Deacon,’ said Sister Conchita

clearly. ‘I don’t think its inhabitants would take kindly to seeing

a sister being manhandled.’

Deacon looked at the dozen or so men getting closer. With

an impressive display of strength he hurled the sack into the

bottom of the dinghy, scattering its consignment of shells.

‘I won’t forget this,’ he promised vehemently, glaring up as he

cast off. ‘I’m not having some bit of a kid who hasn’t been in the

islands five minutes telling me what to do.’

‘And another thing,’ the nun called after him. ‘Just in case you

have any more illegal shells in that sack, I shall be asking the

Customs Department in the capital to examine it when you get

there.’

Deacon was already rowing the dinghy with vicious strokes

back towards his small trading vessel. Sister Conchita turned with

a grateful and rather tremulous smile to face the approaching

islanders. She realized that, as usual, she had just insisted on

having the last word. It was a failing she was well aware of and

would have to take to confession yet again.

GRAEME KENT

6

2

THE GHOST-CALLER

Sergeant Kella sat on the earthen floor of the beu, the men’s

meeting-house, patiently waiting for the ghost-caller to bring

back the dead.

Most of the men of the coastal village had managed to cram into

the long, thatched building with its smoke-blackened bamboo

walls. According to custom, a smallwooden gong had been struck

with a thick length of creeper to summon the assembly.

Kella could hear the women and children of the remote

saltwater hamlet talking excitedly outside as they waited for news

of the proceedings to filter from the hut. Most of the men were

eyeing him with suspicion as he sat impassively among them. A

touring police officer would not normally have been allowed

inside the hut, but he was present in his capacity of aofia, the

hereditary peacemaker of the Lau people.

Kella hoped that Chief Superintendent Grice would not hear

about the detour he had made to this village. Back in Honiara

his superior had been explicit in his instructions.

‘You’re going to Malaita for one reason only,’ he had told

Kella. ‘You are to make inquiries about Dr Mallory, nothing else.

After your last little episode over there, I said I’d never send you

back. But you speak the language. I take it that you can ask a few

simple questions and come back with the answers?’

7

Hurriedly Kella had assured the police chief that he could.

After six months sitting behind a desk in the capital he would

have promised almost anything to get out on tour again. Now

here he was, only two days into his journey, and already he was

disobeying instructions.

The village headman entered the hut. He was a plump,

self-satisfied man clad in new shorts and singlet and exuding the

confidence of someone who owned good land. With a few

exceptions, the Lau area chieftains were not hereditary but were

chosen for their conspicuous distribution of wealth. This man

would have achieved his position for the number of feasts he had

hosted, not for any fighting prowess.

The headman cleared his throat. ‘We are here to find out who

killed Senda Iabuli,’ he muttered grudgingly in the local dialect.

Plainly he had not wanted the meeting to take place. ‘To do this

we have sent for the ghost-caller, the ngwane inala. He will tell

us who the killer is.’

The ghost-caller was sitting with his back to the wall, facing

the other men. He was in his sixties, small and emaciated, his

meagre frame racked periodically with hacking coughs. He wore

only a brief thong about his loins. His face and body were

criss-crossed with gaudy and intricate patterns painted on with

the magic lime. Barely visible beneath the decorations on his face

were a number of vertical scars, slashed there long ago when he

first set out to learn the calling incantations. Laid out on the

ground before him were two stringed hunting bows, some leaves

of the red dracaena plant, a few coconuts and a carved wooden

bowl containing trochus shells.

According to the gossip Kella had managed to pick up since

his arrival at the village, the ghost-caller had been summoned to

investigate the sudden death of Senda Iabuli, a perfectly

undistinguished villager, an elderly widower with no surviving

children.

GRAEME KENT

8

Iabuli’s first and only claim to notoriety had occurred a month

before. Early one morning he had been on his way to work in

his garden on the side of a mountain just outside the village. He

had, as always, crossed a ravine by way of a narrow swing bridge

consisting of creepers and logs lashed together. As he had made

his precarious way to the far side, a sudden gust of wind had

caught the old man and sent him toppling helplessly hundreds of

feet down into the valley below.

The event had been witnessed by a group of men hunting wild

pigs. It had taken them most of the morning to descend the

tree-covered slope into the ravine to recover the body of the old

villager. To their amazement, they had discovered Senda Iabuli

alive and well, if considerably shaken and winded. His fall had

been broken by the leafy tops of the trees, from which he had

slithered down to end up dazed and bruised on a pile of moss at

the foot of a casuarina tree.

The old man had been helped back to the village, confused

and shaking, but apparently none the worse for his experience.

For several weeks he had resumed his customary innocuous

existence. Then one morning he had been found dead in his hut.

Normally that would have been the end of the matter, but for

some unfathomable reason a relative of Iabuli had demanded an

investigation into his death. This was the family’s right by

custom and had caused the headman to send for the ghost-caller.

Kella had heard of the events and had invited himself to the

ceremony.

The ghost-caller picked up one of the red dracaena leaves and

split it down the middle. He wrapped one half around the other

to strengthen it. Then he placed the reinforced leaf in the carved

bowl. Next, he shuffled the two stringed bows on the ground

before him. Each was a little less than full size, fashioned of palm

wood, with strings of twisted red and yellow vegetable fibres.

The bows represented two Lau ghosts, the spirits of men who

DEVIL-DEVIL

9

had once walked the earth. The ghost-caller threw back his head

and started to chant an incantation in a high-pitched, keening

tone.

The calling went on for more than an hour as the caller

begged the right spirits to enter the beu. They had a long way to

come, for the souls of the dead resided on the island of Momulo,

far away. Suddenly the chanting ended. The caller stiffened, his

back rigid and his eyes closed.

‘The ghosts ride,’ murmured the headman, nodding sagely, as

if these events were all his doing. Some of the elders nodded

obsequious agreement. The custom man before them was now

possessed of the spirits of the departed agalo.

‘Who comes?’ demanded the ghost-caller. Spasms racked his

body. Voices began to emerge from his mouth. There were two

of them, speaking in different pitches. Kella had been expecting

them both. The ghost-caller had taken no chances, adhering to

the main ancestral ghosts of the region, ones everyone present

would know. He had selected Takilu, the war god, and Sina

Kwao of the red hair, who had once killed the giant lizard which

had threatened to devour all of Malaita. Only a ghost-caller was

allowed to address these spirits by their names.

As each ghost spoke, the relevant bow quivered on the

ground. The caller was good, thought Kella. The police sergeant

had been watching the emaciated man closely, and was sure that

there were no threads connecting the weapons to the ghostcaller,

which could be twitched surreptitiously to make them

flutter. He could only assume that the custom man was

drumming on the ground with his iron-hard heels to set up the

necessary vibrations.

THE GLORY SHELL

Sister Conchita clung to the sides of the small dugout canoe as

the waves pounded over the frail vessel, soaking its two

occupants. In front of her the Malaitan scooped his paddle into

the water, trying to keep the craft on an even balance. Sister

Conchita could see the coastal village a hundred yards away. The

beach was crowded with islanders. She wondered whether it had

been worth the perilous sea journey just to see the shark-calling

ceremony when all she wanted was a shower and a meal. Of

course it was, she told herself severely. If she intended serving

God in the Solomons then she had to get to know everything

about the islands.

The half-naked islander in front of her suddenly gave a scream

of terror. Turning, he thrust the paddle into the sister’s hands and

dived over the side of the canoe, disappearing into the frothing

white foam. Sister Conchita sat rigid with apprehension, the

pitted wooden blade clutched loosely in her hands. Bereft of

the islander’s control, the canoe started pitching and swinging

wildly.

For a moment all that Sister Conchita wanted to do was to

cower helplessly in the bucking wooden frame. Then her

customary resourcefulness took over. Snap out of it, she thought

grimly. You got yourself into this hole, better get out of it the

1

same way, girl. Muttering a fervent prayer, she tightened her

grip on the paddle and thrust it with all her force into the water.

For the next five minutes the wiry young sister fought the sea.

The momentum of the current was sending her at breakneck

speed in the direction of the beach and the watching islanders,

but the waves were crashing over the canoe at an angle, buffeting

it from side to side. Several times the entire tree shell was

submerged beneath the surface, but on each occasion it surfaced

sufficiently for the sodden nun, coughing and gasping, to resume

her paddling.

Doggedly she kept the prow of the canoe pointing at the

beach. After an apparent eternity of choking, muscle-aching

effort the shore actually seemed to be getting closer. One final

shock of a wave descended on the canoe and hurled it sprawling

up into the shallows off the beach.

Half a dozen brawny, cheering Melanesian men in skimpy

loincloths splashed into the water and laughingly hauled the

canoe up on to the sand. The crowd of assembled islanders broke

into delighted applause. Dazedly Sister Conchita stood up and

limped out of the beached craft.

Gradually her vision cleared. She blinked hard. Standing in

front of her, joining vigorously in the acclamation among the

large crowd, was the islander who had discarded his paddle and

left her to fight the sea alone. Struggling for breath, Sister

Conchita fought for the words adequately to express her opinion

of him.

‘They’ve just been pulling your leg, sister,’ drawled a

contemptuous voice from behind her. ‘They wanted to see what

you were made of. You didn’t do so bad. Most sheilas just stay

in the boat screaming bloody murder.’

The nun turned to see John Deacon, unshaven and clad in

khaki shorts and shirt, regarding her coolly from the edge of the

crowd.

GRAEME KENT

2

‘Mr Deacon,’ said Sister Conchita, trying to keep her balance.

Deacon was an Australian who managed a local copra plantation.

She did not like him, suspecting him of ill-treating his labourers.

However, she always tried, she suspected in vain, to conceal her

feelings.

‘Local custom,’ explained the stocky, broad-shouldered Australian

laconically. ‘Any stranger approaching the beach, the

guide jumps overboard. Actually the current is bound to bring

the canoe up on to the shore, but if you don’t know that, it can

be a mite disconcerting.’

‘You can say that again,’ said Sister Conchita.

‘At least you had a go,’ acknowledged the plantation manager.

‘The natives like guts.’

‘Have you come for the ceremony?’ asked Sister Conchita

politely, trying to change the subject. She did not wish to be

reminded too much of her undignified arrival.

The Australian snorted with derision. ‘I don’t believe in

superstition,’ he told her. His eyes scanned her tattered, oncewhite

habit. ‘Any superstition,’ he told her with emphasis. ‘I’m

here to pick up a cargo.’

Suddenly Deacon was swept aside by a phalanx of island

women, offering the nun rough blankets with which to dry

herself, together with a husk of coconut milk. In a chattering

group they conducted her to a site at the water’s edge and waited

eagerly with her. An artificial lagoon about twenty yards in

diameter had been constructed there with piles of stones marking

its edges, and an aperture on the seaward side to allow fish to

swim in and out.

As the nun watched, an old man in tattered shorts and singlet

emerged from one of the huts and walked down towards the

stones. A profusion of ancient bone charms rattled on a string

around his neck. A naked small boy of about ten years of age

accompanied him.

DEVIL-DEVIL

3

‘Fa’atabu,’ muttered an awed woman. She translated for the

nun’s benefit. ‘This one is the shark-caller,’ she said, indicating

the old man.

Four islanders splashed out into the shallow waters of the shark

area. They were carrying large flat stones, which they banged

together under the water. Simultaneously the shark-caller started

chanting in a high, tuneless voice. The crowd, which had swollen

in numbers to several hundred, looked on in expectant silence.

For several minutes nothing happened. Then a reverent

murmur went round the crowd. The fins of half a dozen sharks

could be seen entering the enclosure.

The men, still clashing the stones together, fled from the

water. Women picked up a few baskets of raw pork and placed

them at the water’s edge before withdrawing hastily. Completely

unperturbed, the boy hoisted one of the baskets up on to his

shoulder and staggered out with it into the water, to a depth of

several feet. To the accompaniment of screams and shouts from

the crowd on the shore the sharks began to swim steadily towards

the boy.

Sister Conchita found herself clenching her fists at the sight.

The boy stood still for a moment. Then he reached up into the

basket and started feeding the sharks lumps of raw meat,

dropping these into the water just in front of him. As the sharks

approached, accepting the food, the boy began to caress them.

Throughout, the shark-caller continued his keening.

Sister Conchita looked on, fascinated by the sight. Out of the

corner of her eye she became aware of Deacon and two

Melanesians carrying a bulky sack along the ramshackle wooden

jetty protruding into the sea. A dinghy was tethered there,

bobbing in the water. Farther out to sea she could see the

Australian’s trading vessel at anchor.

The sister did not want to leave the ceremony but she thought

that it would only be courteous to say goodbye to the brusque

GRAEME KENT

4

plantation manager. Reluctantly she slipped through the crowd

and made her way along the wharf. Deacon and his helpers were

trying to load the sack into the heaving dinghy. The islanders

were struggling to lower the sack to Deacon, waiting impatiently

below. As she approached, one of the Melanesians dropped his

end of the bulging sack. It burst open, disgorging a cascade of

seashells.

Sister Conchita increased her pace to see if she could help.

Some of the shells rolled across the wooden platform and nestled

at her feet. The nun stooped to pick them up.

‘Leave that; we’ll sort it!’ ordered Deacon, scrambling up from

the dinghy.

Sister Conchita ignored him. She had cradled three shells in

her hands and was examining them with increasing excitement

and anxiety. She would have recognized them anywhere. Before

she had left Chicago she had attended a museum display of South

Pacific seashells. The ones in her hands were a delicate golden

brown in colour, with a round base tapering exquisitely to a

point.

‘Are you deaf? I said I’ll take those!’ shouted Deacon,

lumbering towards her.

Sister Conchita was intimidated by the Australian’s looming

presence but stubbornly she clutched the beautiful shells to her.

‘I think not, Mr Deacon,’ she said, refusing to take a pace

backwards, although every instinct warned her to get away from

the plantation manager. ‘I believe these are glory shells,’ she went

on. ‘You have no right to be taking them off the island. They’re

a part of the culture of the Solomons.’

The Conus gloriamaris, or Glory of the Seas, was the rarest of

all seashells to be found in the Solomons, sought after in vain by

almost every islander. It fetched over a thousand dollars among

collectors. Its export was expressly forbidden by the government.

‘Mind your own business!’ grunted Deacon. ‘Or . . .’

DEVIL-DEVIL

5

‘Or what, Mr Deacon?’ asked Sister Conchita, still standing

her ground, although she was conscious that she was trembling.

It had been a long time since she had been exposed to an

example of such apparently uncontrollable wrath.With relief she

realized that a group of village men, attracted by the altercation

between the two expatriates, had abandoned the shark-calling

ceremony temporarily and were hurrying along the jetty behind

them.

‘This is a Catholic village, Mr Deacon,’ said Sister Conchita

clearly. ‘I don’t think its inhabitants would take kindly to seeing

a sister being manhandled.’

Deacon looked at the dozen or so men getting closer. With

an impressive display of strength he hurled the sack into the

bottom of the dinghy, scattering its consignment of shells.

‘I won’t forget this,’ he promised vehemently, glaring up as he

cast off. ‘I’m not having some bit of a kid who hasn’t been in the

islands five minutes telling me what to do.’

‘And another thing,’ the nun called after him. ‘Just in case you

have any more illegal shells in that sack, I shall be asking the

Customs Department in the capital to examine it when you get

there.’

Deacon was already rowing the dinghy with vicious strokes

back towards his small trading vessel. Sister Conchita turned with

a grateful and rather tremulous smile to face the approaching

islanders. She realized that, as usual, she had just insisted on

having the last word. It was a failing she was well aware of and

would have to take to confession yet again.

GRAEME KENT

6

2

THE GHOST-CALLER

Sergeant Kella sat on the earthen floor of the beu, the men’s

meeting-house, patiently waiting for the ghost-caller to bring

back the dead.

Most of the men of the coastal village had managed to cram into

the long, thatched building with its smoke-blackened bamboo

walls. According to custom, a smallwooden gong had been struck

with a thick length of creeper to summon the assembly.

Kella could hear the women and children of the remote

saltwater hamlet talking excitedly outside as they waited for news

of the proceedings to filter from the hut. Most of the men were

eyeing him with suspicion as he sat impassively among them. A

touring police officer would not normally have been allowed

inside the hut, but he was present in his capacity of aofia, the

hereditary peacemaker of the Lau people.

Kella hoped that Chief Superintendent Grice would not hear

about the detour he had made to this village. Back in Honiara

his superior had been explicit in his instructions.

‘You’re going to Malaita for one reason only,’ he had told

Kella. ‘You are to make inquiries about Dr Mallory, nothing else.

After your last little episode over there, I said I’d never send you

back. But you speak the language. I take it that you can ask a few

simple questions and come back with the answers?’

7

Hurriedly Kella had assured the police chief that he could.

After six months sitting behind a desk in the capital he would

have promised almost anything to get out on tour again. Now

here he was, only two days into his journey, and already he was

disobeying instructions.

The village headman entered the hut. He was a plump,

self-satisfied man clad in new shorts and singlet and exuding the

confidence of someone who owned good land. With a few

exceptions, the Lau area chieftains were not hereditary but were

chosen for their conspicuous distribution of wealth. This man

would have achieved his position for the number of feasts he had

hosted, not for any fighting prowess.

The headman cleared his throat. ‘We are here to find out who

killed Senda Iabuli,’ he muttered grudgingly in the local dialect.

Plainly he had not wanted the meeting to take place. ‘To do this

we have sent for the ghost-caller, the ngwane inala. He will tell

us who the killer is.’

The ghost-caller was sitting with his back to the wall, facing

the other men. He was in his sixties, small and emaciated, his

meagre frame racked periodically with hacking coughs. He wore

only a brief thong about his loins. His face and body were

criss-crossed with gaudy and intricate patterns painted on with

the magic lime. Barely visible beneath the decorations on his face

were a number of vertical scars, slashed there long ago when he

first set out to learn the calling incantations. Laid out on the

ground before him were two stringed hunting bows, some leaves

of the red dracaena plant, a few coconuts and a carved wooden

bowl containing trochus shells.

According to the gossip Kella had managed to pick up since

his arrival at the village, the ghost-caller had been summoned to

investigate the sudden death of Senda Iabuli, a perfectly

undistinguished villager, an elderly widower with no surviving

children.

GRAEME KENT

8

Iabuli’s first and only claim to notoriety had occurred a month

before. Early one morning he had been on his way to work in

his garden on the side of a mountain just outside the village. He

had, as always, crossed a ravine by way of a narrow swing bridge

consisting of creepers and logs lashed together. As he had made

his precarious way to the far side, a sudden gust of wind had

caught the old man and sent him toppling helplessly hundreds of

feet down into the valley below.

The event had been witnessed by a group of men hunting wild

pigs. It had taken them most of the morning to descend the

tree-covered slope into the ravine to recover the body of the old

villager. To their amazement, they had discovered Senda Iabuli

alive and well, if considerably shaken and winded. His fall had

been broken by the leafy tops of the trees, from which he had

slithered down to end up dazed and bruised on a pile of moss at

the foot of a casuarina tree.

The old man had been helped back to the village, confused

and shaking, but apparently none the worse for his experience.

For several weeks he had resumed his customary innocuous

existence. Then one morning he had been found dead in his hut.

Normally that would have been the end of the matter, but for

some unfathomable reason a relative of Iabuli had demanded an

investigation into his death. This was the family’s right by

custom and had caused the headman to send for the ghost-caller.

Kella had heard of the events and had invited himself to the

ceremony.

The ghost-caller picked up one of the red dracaena leaves and

split it down the middle. He wrapped one half around the other

to strengthen it. Then he placed the reinforced leaf in the carved

bowl. Next, he shuffled the two stringed bows on the ground

before him. Each was a little less than full size, fashioned of palm

wood, with strings of twisted red and yellow vegetable fibres.

The bows represented two Lau ghosts, the spirits of men who

DEVIL-DEVIL

9

had once walked the earth. The ghost-caller threw back his head

and started to chant an incantation in a high-pitched, keening

tone.

The calling went on for more than an hour as the caller

begged the right spirits to enter the beu. They had a long way to

come, for the souls of the dead resided on the island of Momulo,

far away. Suddenly the chanting ended. The caller stiffened, his

back rigid and his eyes closed.

‘The ghosts ride,’ murmured the headman, nodding sagely, as

if these events were all his doing. Some of the elders nodded

obsequious agreement. The custom man before them was now

possessed of the spirits of the departed agalo.

‘Who comes?’ demanded the ghost-caller. Spasms racked his

body. Voices began to emerge from his mouth. There were two

of them, speaking in different pitches. Kella had been expecting

them both. The ghost-caller had taken no chances, adhering to

the main ancestral ghosts of the region, ones everyone present

would know. He had selected Takilu, the war god, and Sina

Kwao of the red hair, who had once killed the giant lizard which

had threatened to devour all of Malaita. Only a ghost-caller was

allowed to address these spirits by their names.

As each ghost spoke, the relevant bow quivered on the

ground. The caller was good, thought Kella. The police sergeant

had been watching the emaciated man closely, and was sure that

there were no threads connecting the weapons to the ghostcaller,

which could be twitched surreptitiously to make them

flutter. He could only assume that the custom man was

drumming on the ground with his iron-hard heels to set up the

necessary vibrations.

Recenzii

“Truly fabulous ... Sister Conchita and Kella are already committed to a sequel. This is a series, and a writer, to watch.”—Toronto Globe and Mail

“Kent, a prolific author of fiction and nonfiction, fills Devil-Devil with a sparkling plot (complete with an unexpected conclusion) and a rich history of the Solomons and their native people. But it's Kella and Conchita—and Kent's wit—that makes this unusual mystery work, and readers will eagerly await the next installment.”—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Kent’s first mystery is the beginning of a new and promising series.... The atmosphere and setting are integral to both character and plot and lend a unique note to this solid mystery. Definitely a series to watch.”—Booklist

“Kent, a prolific author of fiction and nonfiction, fills Devil-Devil with a sparkling plot (complete with an unexpected conclusion) and a rich history of the Solomons and their native people. But it's Kella and Conchita—and Kent's wit—that makes this unusual mystery work, and readers will eagerly await the next installment.”—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Kent’s first mystery is the beginning of a new and promising series.... The atmosphere and setting are integral to both character and plot and lend a unique note to this solid mystery. Definitely a series to watch.”—Booklist