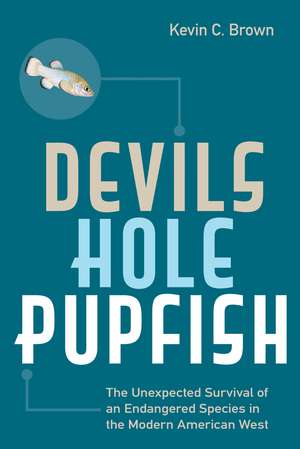

Devils Hole Pupfish: The Unexpected Survival of an Endangered Species in the Modern American West: America's National Parks

Autor Kevin C. Brownen Limba Engleză Paperback – 7 sep 2021 – vârsta ani

Cyprinodon diabolis, or Devils Hole pupfish: a one-inch-long, iridescent blue fish whose only natural habitat is a ten-by-sixty-foot pool near Death Valley, on the Nevada-California border. The rarest fish in the world.

As concern for the future of biodiversity mounts, Devils Hole Pupfish asks how a tiny blue fish—confined to a single, narrow aquifer on the edge of Death Valley National Park in Nevada’s Amargosa Desert—has managed to survive despite numerous grave threats.

For decades, the pupfish has been the subject of heated debate between environmentalists intent on protecting it from extinction and ranchers and developers in the region who need the aquifer’s water to support their livelihoods. Drawing on archival detective work, interviews, and a deep familiarity with the landscape of the surrounding Amargosa Desert, author Kevin C. Brown shows how the seemingly isolated Devils Hole pupfish has persisted through its relationships with some of the West’s most important institutions: federal land management policy, western water law, ecological sciences, and the administration of endangered-species legislation.

The history of this entanglement between people and the pupfish makes its story unique. The species was singled out for protection by the National Park Service, made one of the first “listed” endangered species, and became one of the first controversial animals of the modern environmental era, with one bumper sticker circulating in Nevada in the early 1970s reading “Save the Pupfish,” while another read “Kill the Pupfish.”

But the story of the pupfish should be considered for more than its peculiarity. Moreover, Devils Hole Pupfish explores the pupfish’s journey through modern American history and offers lessons for anyone looking to better understand the politics of water in southern Nevada, the operation of the Endangered Species Act, or the science surrounding desert ecosystems.

As concern for the future of biodiversity mounts, Devils Hole Pupfish asks how a tiny blue fish—confined to a single, narrow aquifer on the edge of Death Valley National Park in Nevada’s Amargosa Desert—has managed to survive despite numerous grave threats.

For decades, the pupfish has been the subject of heated debate between environmentalists intent on protecting it from extinction and ranchers and developers in the region who need the aquifer’s water to support their livelihoods. Drawing on archival detective work, interviews, and a deep familiarity with the landscape of the surrounding Amargosa Desert, author Kevin C. Brown shows how the seemingly isolated Devils Hole pupfish has persisted through its relationships with some of the West’s most important institutions: federal land management policy, western water law, ecological sciences, and the administration of endangered-species legislation.

The history of this entanglement between people and the pupfish makes its story unique. The species was singled out for protection by the National Park Service, made one of the first “listed” endangered species, and became one of the first controversial animals of the modern environmental era, with one bumper sticker circulating in Nevada in the early 1970s reading “Save the Pupfish,” while another read “Kill the Pupfish.”

But the story of the pupfish should be considered for more than its peculiarity. Moreover, Devils Hole Pupfish explores the pupfish’s journey through modern American history and offers lessons for anyone looking to better understand the politics of water in southern Nevada, the operation of the Endangered Species Act, or the science surrounding desert ecosystems.

Preț: 288.50 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 433

Preț estimativ în valută:

55.20€ • 57.64$ • 45.59£

55.20€ • 57.64$ • 45.59£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781647790103

ISBN-10: 1647790107

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 5 line drawings, 12 halftones, 2 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Seria America's National Parks

ISBN-10: 1647790107

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 5 line drawings, 12 halftones, 2 maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Seria America's National Parks

Recenzii

“Scientists who wish to explore the history of their field and to understand how human actions such as political and social movements can doom or save an endangered species are encouraged to read. His writing style is conversational, but not to the book’s detriment; rather, Brown’s prose is easily accessible to historians and scientists alike, as well as the general public.”

—David McCaskey, H-Net Reviews

“In this fine book, Kevin Brown shows convincingly why a tiny fish matters in a big way. By tracking its rich history and the political entanglements it has engendered, he raises essential questions – ones specific to the pupfish, but extensible to other endangered species: Who gets to decide their fate? What survival tactics work best, and how long should those efforts continue? Ultimately, Brown illustrates one of the most important lessons of all: that life can be simultaneously persistent, adaptable, and fragile.”

—Daniel Lewis, author of Belonging on an Island: Birds, Extinction, and Evolution in Hawaii

“This crystalline gem of a book considers the improbable survival of a small, obscure, and critically endangered aquatic animal, the Devils Hole pupfish, that has the most restricted habitat of any known vertebrate species. Deeply researched, engagingly presented, and convincingly argued, this is a remarkable story, one that is important and exceptionally well told.”

—Mark V. Barrow Jr, professor of history, Virginia Tech, and author of Nature’s Ghost: Confronting Extinction from the Age of Jefferson to the Age of Ecology

"A delightful and thought-provoking yarn, rich in good humor--and deep environmental meaning--in the best traditions of the new American west."

—Joshua P. Howe, professor of history and environmental studies, Reed College, and author of Behind the Curve: Science and the Politics of Global Warming and Making Climate Change History

"You have probably never heard of the Devils Hole pupfish. In his fine and widely ranging book, Kevin Brown reveals that this “one inch long, twitchy blue fish” is a microcosm of the contentious histories of wilderness, science, water, and policy in the modern American West. This tiny fish contains multitudes."

—Anita Guerrini, Oregon State University

—David McCaskey, H-Net Reviews

“In this fine book, Kevin Brown shows convincingly why a tiny fish matters in a big way. By tracking its rich history and the political entanglements it has engendered, he raises essential questions – ones specific to the pupfish, but extensible to other endangered species: Who gets to decide their fate? What survival tactics work best, and how long should those efforts continue? Ultimately, Brown illustrates one of the most important lessons of all: that life can be simultaneously persistent, adaptable, and fragile.”

—Daniel Lewis, author of Belonging on an Island: Birds, Extinction, and Evolution in Hawaii

“This crystalline gem of a book considers the improbable survival of a small, obscure, and critically endangered aquatic animal, the Devils Hole pupfish, that has the most restricted habitat of any known vertebrate species. Deeply researched, engagingly presented, and convincingly argued, this is a remarkable story, one that is important and exceptionally well told.”

—Mark V. Barrow Jr, professor of history, Virginia Tech, and author of Nature’s Ghost: Confronting Extinction from the Age of Jefferson to the Age of Ecology

"A delightful and thought-provoking yarn, rich in good humor--and deep environmental meaning--in the best traditions of the new American west."

—Joshua P. Howe, professor of history and environmental studies, Reed College, and author of Behind the Curve: Science and the Politics of Global Warming and Making Climate Change History

"You have probably never heard of the Devils Hole pupfish. In his fine and widely ranging book, Kevin Brown reveals that this “one inch long, twitchy blue fish” is a microcosm of the contentious histories of wilderness, science, water, and policy in the modern American West. This tiny fish contains multitudes."

—Anita Guerrini, Oregon State University

Notă biografică

Kevin C. Brown works with his head and his hands on the east side of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. He is a research associate in the University of California, Santa Barbara’s, Environmental Studies Program, and has also worked as a journalist and as a researcher for the National Park Service and the American Society for Environmental History.

Extras

Introduction: Surviving the Meteor

Sixty thousand years ago, the roof of a water-filled cavern collapsed just east of Death Valley in what is now southern Nye County, Nevada. Channeling a cosmology that saw dark forces in both geological oddities and the wilderness, nineteenth-century Anglo-American visitors gave this place the name "Devils Hole."

This roughly funnel-shaped feature is, improbably, a window into a vast subterranean lake. When you stand on the platform at the top of the Devils Hole fissure and look down to the pool, forty-five feet below, you are staring into an aquifer, a rare vantage point. Water remains a constant ninety-two degrees Fahrenheit in Devils Hole; one researcher diving there said it felt like returning to the womb.3 U.S. Geological Survey divers descended into the darkness to a depth of 436 feet but saw neither bottom nor any evidence of the two teenage divers who disappeared into the abyss in 1965.4 Devils Hole, for all practical purposes, is bottomless.

Deserts are defined by their aridity. But Devils Hole is on the eastern edge of a relatively lush patch of the Amargosa Desert called Ash Meadows. Along with a series of faults that run on a northwest-southeast line near Devils Hole, a network of more than a dozen large springs and numerous seeps discharge some 10,000 gallons of water every minute, producing oases in the desert that stretch across some 50,000 acres of land.5 Another way to think about Ash Meadows is as an island, though instead of being surrounded by water, it is bounded by land that sorely lacks it. Trapped on the island of Ash Meadows, at least twenty-nine kinds of animals and plants have evolved into species, subspecies, or varieties found nowhere else in the world. Ash Meadows is the Galápagos of the Intermountain West.

This book is about one of these species, an inhabitant of the strange pool on the edge of the Ash Meadows oasis, a one-inch long, twitchy blue fish: Cyprinodon diabolis-the Devils Hole pupfish. Despite the unknown depth of Devils Hole, the pool is just ten feet wide by sixty feet long at its surface. The pupfish live only in this small zone near the top of the water column, where invertebrates and algae (i.e., pupfish food) are found. They spawn exclusively in an even more restricted area: a chunk of rock scientists call the "shallow shelf" wedged into the southern third of the pool that is barely submerged below the waterline. The entire species, which at times has had a

population of fewer than forty observed fish, could barely stock a suburban dental office aquarium. The pupfish's only natural home is Devils Hole, and biologists consider the fish to have the smallest habitat for vertebrate species in the entire world. Even within the species-rich island of Ash Meadows, the Devils Hole pupfish is rare and unique, a fact that helped make it a founding member of the U.S. endangered species list when it was created in 1967.

Arriving sometime after Devils Hole became open to air and light-though exactly when is subject to lively debate-the Devils Hole pupfish was shaped by its isolation in an extreme environment. In addition to its high temperature, the water in Devils Hole has very little dissolved oxygen and direct sunlight does not even reach the pool in winter. As a result, more than half of the total annual energy available in Devils Hole comes from plants, insects, and dust falling into the pool; a minority share of energy comes from algae actually growing there. Because it evolved in this energy-poor and high-temperature environment, the Devils Hole pupfish is smaller and less aggressive than other pupfishes-yes, there are others-and unlike these relatives, it rarely even has pelvic fins. In other words, by pupfish standards, C. diabolis is both tiny and wimpy.

Yet the Devils Hole pupfish is a tenacious survivor, enduring not just a harsh physical environment, but also recent American history. Nineteenth-century Anglo-Americans often regarded deserts as places to avoid or navigate across quickly, an attitude in sharp contrast to the Newe (Western Shoshone) and Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute) peoples that have made the deserts around Ash Meadows a homeland. The group that gave Death Valley its dour name—a party of easterners seeking their fortunes in the California gold fields—even passed by Devils Hole on December 23, 1849, with at least two members of the party enjoyed a swim in the pool. Despite the aversion to deserts, by the 1870s, the prospect of extracting precious metals-and wealth- made the Amargosa a home for mining industry, eventually earning Devils Hole the nickname of the "miner's bathtub" from workers living nearby.

The twentieth century brought new uses to the desert around Devils Hole. The U.S. military reserved vast swaths of Nevada and California for airfields, bombing ranges, and a destructive new test site far from the prying eyes of citizens and spies, while the National Park Service promoted tourism and expanded its holdings at its desert parks, including Death Valley National Monument in 1933. (The monument was expanded and redesignated as Death Valley National Park in 1994.) These two very different categories of federal lands sometimes crossed paths at Devils Hole. Just a year before President Truman added Devils Hole to the Death Valley monument, in 1952, the government began testing nuclear weapons north of Devils Hole at the Nevada Test Site. Some blasts-the government ultimately detonated more than 1,000 nuclear weapons on the site-would cause water in Devils Hole to slosh back and forth.

Recent human history has done more, however, than just swirl around the Devils Hole pupfish as it remained safely ensconced in a remote habitat. Instead, the pupfish has become repeatedly entangled in some of the most important changes in how Americans understand, exploit, and protect the West. For this reason, this book is in large measure about how people have since the 1890s wrestled with the existence and meaning of the pupfish. Scientists, federal and state government officials, ranchers, politicians, developers, and even the U.S. Supreme Court have all weighed in. These engagements have produced a changing scientific classification of the Devils Hole pupfish,

debates over the aims of the national park system, an extensive battle over water rights, and the power of the federal government, and a continuing struggle to manage a species with

very small population.

And yet-despite its turbulent recent history and extreme habitat-the pupfish remain, an act of survival that is a true wonder. It took me years to realize that this modern persistence was, in addition to a minor miracle, also a conundrum in need of an explanation. Across a century when humans have radically altered the deserts, springs, and atmosphere of the American West, and as many endemic species have gone extinct-including some of the Devils Hole pupfish's close genetic relatives and geographic neighbors-just how exactly has the Devils Hole pupfish persisted?

Sixty thousand years ago, the roof of a water-filled cavern collapsed just east of Death Valley in what is now southern Nye County, Nevada. Channeling a cosmology that saw dark forces in both geological oddities and the wilderness, nineteenth-century Anglo-American visitors gave this place the name "Devils Hole."

This roughly funnel-shaped feature is, improbably, a window into a vast subterranean lake. When you stand on the platform at the top of the Devils Hole fissure and look down to the pool, forty-five feet below, you are staring into an aquifer, a rare vantage point. Water remains a constant ninety-two degrees Fahrenheit in Devils Hole; one researcher diving there said it felt like returning to the womb.3 U.S. Geological Survey divers descended into the darkness to a depth of 436 feet but saw neither bottom nor any evidence of the two teenage divers who disappeared into the abyss in 1965.4 Devils Hole, for all practical purposes, is bottomless.

Deserts are defined by their aridity. But Devils Hole is on the eastern edge of a relatively lush patch of the Amargosa Desert called Ash Meadows. Along with a series of faults that run on a northwest-southeast line near Devils Hole, a network of more than a dozen large springs and numerous seeps discharge some 10,000 gallons of water every minute, producing oases in the desert that stretch across some 50,000 acres of land.5 Another way to think about Ash Meadows is as an island, though instead of being surrounded by water, it is bounded by land that sorely lacks it. Trapped on the island of Ash Meadows, at least twenty-nine kinds of animals and plants have evolved into species, subspecies, or varieties found nowhere else in the world. Ash Meadows is the Galápagos of the Intermountain West.

This book is about one of these species, an inhabitant of the strange pool on the edge of the Ash Meadows oasis, a one-inch long, twitchy blue fish: Cyprinodon diabolis-the Devils Hole pupfish. Despite the unknown depth of Devils Hole, the pool is just ten feet wide by sixty feet long at its surface. The pupfish live only in this small zone near the top of the water column, where invertebrates and algae (i.e., pupfish food) are found. They spawn exclusively in an even more restricted area: a chunk of rock scientists call the "shallow shelf" wedged into the southern third of the pool that is barely submerged below the waterline. The entire species, which at times has had a

population of fewer than forty observed fish, could barely stock a suburban dental office aquarium. The pupfish's only natural home is Devils Hole, and biologists consider the fish to have the smallest habitat for vertebrate species in the entire world. Even within the species-rich island of Ash Meadows, the Devils Hole pupfish is rare and unique, a fact that helped make it a founding member of the U.S. endangered species list when it was created in 1967.

Arriving sometime after Devils Hole became open to air and light-though exactly when is subject to lively debate-the Devils Hole pupfish was shaped by its isolation in an extreme environment. In addition to its high temperature, the water in Devils Hole has very little dissolved oxygen and direct sunlight does not even reach the pool in winter. As a result, more than half of the total annual energy available in Devils Hole comes from plants, insects, and dust falling into the pool; a minority share of energy comes from algae actually growing there. Because it evolved in this energy-poor and high-temperature environment, the Devils Hole pupfish is smaller and less aggressive than other pupfishes-yes, there are others-and unlike these relatives, it rarely even has pelvic fins. In other words, by pupfish standards, C. diabolis is both tiny and wimpy.

Yet the Devils Hole pupfish is a tenacious survivor, enduring not just a harsh physical environment, but also recent American history. Nineteenth-century Anglo-Americans often regarded deserts as places to avoid or navigate across quickly, an attitude in sharp contrast to the Newe (Western Shoshone) and Nuwuvi (Southern Paiute) peoples that have made the deserts around Ash Meadows a homeland. The group that gave Death Valley its dour name—a party of easterners seeking their fortunes in the California gold fields—even passed by Devils Hole on December 23, 1849, with at least two members of the party enjoyed a swim in the pool. Despite the aversion to deserts, by the 1870s, the prospect of extracting precious metals-and wealth- made the Amargosa a home for mining industry, eventually earning Devils Hole the nickname of the "miner's bathtub" from workers living nearby.

The twentieth century brought new uses to the desert around Devils Hole. The U.S. military reserved vast swaths of Nevada and California for airfields, bombing ranges, and a destructive new test site far from the prying eyes of citizens and spies, while the National Park Service promoted tourism and expanded its holdings at its desert parks, including Death Valley National Monument in 1933. (The monument was expanded and redesignated as Death Valley National Park in 1994.) These two very different categories of federal lands sometimes crossed paths at Devils Hole. Just a year before President Truman added Devils Hole to the Death Valley monument, in 1952, the government began testing nuclear weapons north of Devils Hole at the Nevada Test Site. Some blasts-the government ultimately detonated more than 1,000 nuclear weapons on the site-would cause water in Devils Hole to slosh back and forth.

Recent human history has done more, however, than just swirl around the Devils Hole pupfish as it remained safely ensconced in a remote habitat. Instead, the pupfish has become repeatedly entangled in some of the most important changes in how Americans understand, exploit, and protect the West. For this reason, this book is in large measure about how people have since the 1890s wrestled with the existence and meaning of the pupfish. Scientists, federal and state government officials, ranchers, politicians, developers, and even the U.S. Supreme Court have all weighed in. These engagements have produced a changing scientific classification of the Devils Hole pupfish,

debates over the aims of the national park system, an extensive battle over water rights, and the power of the federal government, and a continuing struggle to manage a species with

very small population.

And yet-despite its turbulent recent history and extreme habitat-the pupfish remain, an act of survival that is a true wonder. It took me years to realize that this modern persistence was, in addition to a minor miracle, also a conundrum in need of an explanation. Across a century when humans have radically altered the deserts, springs, and atmosphere of the American West, and as many endemic species have gone extinct-including some of the Devils Hole pupfish's close genetic relatives and geographic neighbors-just how exactly has the Devils Hole pupfish persisted?

Cuprins

Contents

Preface: A Note on Usage

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1.What's in a Name?

2.To Protect and Conserve

3.Beneficial Use

4.Save the Pupfish

5.Kill the Pupfish

6.After Victory

Conclusion: This is Forever

List of Abbreviations

Bibliography

About the Author

Preface: A Note on Usage

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1.What's in a Name?

2.To Protect and Conserve

3.Beneficial Use

4.Save the Pupfish

5.Kill the Pupfish

6.After Victory

Conclusion: This is Forever

List of Abbreviations

Bibliography

About the Author

Descriere

The Devils Hole pupfish is one of the rarest vertebrate animals on the planet; its only natural habitat is a ten-by-sixty-foot pool near Death Valley, on the Nevada—California border. Isolation in Devils Hole made the fish different from its close genetic relatives, but as Devils Hole Pupfish explores, what has made the species a survivor is its many surprising connections to the people who have studied, ignored, protested or protected it.