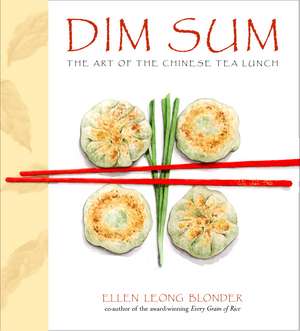

Dim Sum

Autor Ellen Leong Blonderen Limba Engleză Hardback – 3 iul 2002

Anyone who has enjoyed the pleasures of a dim sum meal has inevitably wondered what it would be like to create these treats at home. The answer, surprisingly, is that most are quite simple to make. From dumplings to pastries, Dim Sum is filled with simple, foolproof recipes, complete with clear step-by-step illustrations to explain the art of forming, filling, and folding dumpling wrappers and more. Ellen Blonder offers her favorite versions of traditional Pork and Shrimp Siu Mai, Turnip Cake, and Shrimp Ha Gow, each bite vibrantly flavored, plus recipes for hearty sticky rice dishes, refreshing sautéed greens, tender baked or steamed buns, and a variety of pastries and desserts—all the ingredients required for an authentic, restaurant-style dim sum feast. Practical advice on designing a tea lunch menu and making dim sum ahead of time round out this irresistible collection.

Lovingly created from years of tasting, refining, and seeking out the best dim sum recipes from San Francisco to Hong Kong, Dim Sum is a gem that any student of Chinese cooking will treasure.

Preț: 118.59 lei

Preț vechi: 140.54 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 178

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.69€ • 23.56$ • 18.92£

22.69€ • 23.56$ • 18.92£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-08 martie

Livrare express 15-21 februarie pentru 54.54 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780609608876

ISBN-10: 0609608878

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 196 x 218 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Clarkson N Potter Publishers

ISBN-10: 0609608878

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 196 x 218 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Clarkson N Potter Publishers

Recenzii

Praise for Every Grain of Rice

“Part family chronicle, part cookbook, and all heart, this is a really wonderful book.” —Ruth Reichl

“Enchanting watercolors are among the book’s pleasures. . . . These dishes are a joy to cook, not only for their ultimate goodness but also because the authors and their families are so much a part of each dish.” —New York Times

“Graceful recollections of family and food are scattered among the recipes, along with Blonder’s harmonious, informative drawings.” —Gourmet magazine

“Charming watercolor illustrations . . . Learning new techniques was a bonus to this lovely book full of good food.” —Fine Cooking magazine

“A book filled with personality, warm stories, and recipes that reflect the Chinese table in America.”

—Chicago Tribune

“Certain to charm and delight readers, even noncooks, this is highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

“Every Grain of Rice mixes a variety of recipes with lovely reminiscences of family lore. Combined with the beautiful (and helpful) illustrations by Blonder and the high quality of production, the cookbook is a small gem.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“Part family chronicle, part cookbook, and all heart, this is a really wonderful book.” —Ruth Reichl

“Enchanting watercolors are among the book’s pleasures. . . . These dishes are a joy to cook, not only for their ultimate goodness but also because the authors and their families are so much a part of each dish.” —New York Times

“Graceful recollections of family and food are scattered among the recipes, along with Blonder’s harmonious, informative drawings.” —Gourmet magazine

“Charming watercolor illustrations . . . Learning new techniques was a bonus to this lovely book full of good food.” —Fine Cooking magazine

“A book filled with personality, warm stories, and recipes that reflect the Chinese table in America.”

—Chicago Tribune

“Certain to charm and delight readers, even noncooks, this is highly recommended.”

—Library Journal

“Every Grain of Rice mixes a variety of recipes with lovely reminiscences of family lore. Combined with the beautiful (and helpful) illustrations by Blonder and the high quality of production, the cookbook is a small gem.” —San Francisco Chronicle

Notă biografică

Ellen Leong Blonder is a professional illustrator and designer with numerous licensed product lines. Her first cookbook, Every Grain of Rice, written with her aunt Annabel Low, won the IACP award for best cookbook in the American category. She lives with her husband, Nick, in Mill Valley, California.

Extras

The Role of Tea

Legend has tea being discovered accidentally around 3000 b.c., when tea leaves blew into an outdoor cooking vessel being used to boil water. It was immediately appreciated for its refreshing flavor, and the eventual discovery of its medicinal value and ability to enhance alertness led to its increased use.

Tea was brewed from fresh leaves until the third century b.c., when drying and processing tremendously widened its popularity. Tea has been cultivated commercially in China for at least 1,800 years. Through the centuries, it has served as currency, as payment of taxes to emperors, and as a key factor in the development of porcelain, world trade, and international relations.

While the earliest teahouses served nothing but tea, that gradually changed. Starting with nuts and seeds, accompaniments became more and more elaborate, until "having tea" came to connote enjoying a meal at which dim sum played the central role.

Tea has evolved, too, into countless varieties, but every tea can still be classified as belonging to one of three categories: green, semi-fermented, or black (called red in China). All come from the same shrub, Camellia sinensis. Differences arise from processing techniques. Leaves for green tea are either wilted or not, then pan-fried, steamed, or fired in an oven to prevent oxidation and enzyme action. Leaves for semi-fermented and black teas are wilted, then bruised to allow oxidation to different degrees; this triggers enzymes to create chemical changes, producing tea with more color and less astringency. A final firing stops the process and dries the leaves.

Further variations in tea result from differing soils, climates, time of year the leaves are picked, which leaves are picked, whether leaves are wilted in the sun or shade, and whether flowers or other ingredients are added to scent the tea.

Choosing a Tea

The first question you will be asked when you are seated at a dim sum restaurant is, "What tea will you have?" Here are some favorites you may want to try, either at a restaurant or at home:

Dragon Well, or lung ching, is a mellow green tea celebrated for its bright color and cooling effect. The highest grade is picked from tiny, very young buds and leaves, then dried flat, and the skill required to process them contributes to its high cost.

Gunpowder, or pingshui, is a strong green tea named for the pelletlike shape of its tightly rolled leaves. It is also known as pearl tea, or zhucha, because of its appearance.

Jasmine, or moli huacha, is a green or semi-fermented oolong tea with jasmine flowers added. It is refreshingly astringent, with a delicate flower fragrance; the oolong variety is fuller, with a more lingering aftertaste. Jasmine is often the default tea you will be given if you don't make a choice.

Keemun, or qihong, is known as the king or champagne of black teas, for its roselike fragrance, slightly smoky taste, and deep amber color.

Lychee, or lizhi hongcha, is a black tea scented with the juice of lychee fruit, which also gives it a sweet, mellow, flowery aroma.

Oolong refers to a group of semi-fermented teas, less astringent than green teas, with a floral aftertaste. These include ti kwan yin and some jasmine teas.

Pu-erh (also pronounced po nay or bo lay), a semi-fermented tea, is a popular dim sum tea because of its reputed ability to counteract rich food and reduce cholesterol. This is the tea I order if I plan to indulge in deep-fried dim sum. It has an earthy, mellow flavor.

Ti Kwan Yin (also spelled tieguanyin), the Iron Goddess of Mercy, lends her name to this most famous oolong tea, prized for its orchidlike aroma.

Brewing Tea

There are many disagreements about how to brew perfect tea, with different opinions on correct water temperature, whether to use a tea ball or tea bags, how long to steep or infuse the tea, how much tea to use, and whether to reuse the leaves for a second pot. You will no doubt develop your own preferences, but for starters, here are some suggestions.

For the freshest-tasting tea, start with cold water in your kettle. While it is boiling, fill your teapot with hot water to warm it. Just before the water boils, empty the teapot and measure about 1 teaspoon of tea leaves into the pot for each cup of water you plan to use. If you use a perforated metal tea ball, do not overfill it, because the leaves need room to expand.

Pour the boiling water directly over the leaves and steep them for 3 to 5 minutes. (Some people first "wash" the dry tea leaves with a little boiling water, pouring it off immediately, then filling the pot with fresh boiling water.) Green teas require less steeping time than semi-fermented and black teas. Stronger tea is made by using more leaves, not more time. Longer steeping may result in bitter tea, so you may want to transfer the tea to another heated pot or, as many Chinese households do, to a heated thermos.

I don't mind a few tea leaves in the bottom of my cup, but if you're fussier, use a tea strainer when you pour your tea into the cup.

More boiling water may be added to the teapot for a second infusion. In fact, some connoisseurs insist the second infusion is best.

With a Chinese meal, whether to serve tea with or after the food is a regional preference, but tea is always served with dim sum. In any case, never add sugar, milk, or lemon to the tea.

Steamed Dumplings

When most people think of dim sum, they probably think of dumplings first. Coax a waitress to lift the lids from the stacked steamers on her cart and you'll be tantalized by translucent wheat starch dumplings with myriad fillings-delectable mouthfuls of pork, shrimp, scallops, or vegetables. Most dumplings are steamed, their wrappers cleverly twisted and pleated into fanciful shapes. The most common, ha gow, is instantly recognizable by its delicately pleated exterior. Siu mai shows off its filling above a ruffled collar. Other dumplings are folded into triangles, crescents, and twisted circles.

Setting up a Steamer

Most steamed dishes are cooked over rapidly boiling water; the plate of food is kept elevated on a stand above the water level. The pot must be large enough to allow steam to circulate around the plate, and the pot should have a tight-fitting lid. A wok with a high, domed lid or a wide pasta pot can work well as a steamer.

If you plan to steam a lot, invest in a multitiered metal or bamboo steamer from Chinatown. Aluminum or stainless steel steamers have a bottom section to hold water, two tiers with perforated bottoms for steam to circulate through, and a tight lid. Advantages of a metal steamer are that the bottom section can double as a pot, and it is the best choice for steaming buns.

Bamboo steamer baskets are meant to fit snugly over an open wok filled with boiling water. The bottom of each tier is made from bamboo slats; the sides are fashioned from several layers of split bamboo lashed together. The ingeniously woven top holds in steam remarkably well; it is used instead of a wok lid. Advantages of bamboo steamers are that they impart a wonderful, subtle scent; they work as well as metal steamers for steaming buns; and they are pretty enough to hang on the wall or double as baskets. They also seem to improve with age; mine have lasted many years.

To steam foods, add water to the pot or wok to a depth of about 1 1/2 to 2 inches. If you are using a steamer, fill the bottom section two-thirds full with water.

Bring the water to a boil. Place the pan or plate of food on the stand in a pot or wok and cover it with a lid. If using a steamer, place the plate of food on a tier and stack the steamer together. Steam the food over high heat. Replenish the pot with boiling water as necessary between batches, and check the water level from time to time for dishes that require long cooking times.

What's in a Dough?

Most of the dumplings in this book use one of two basic dumpling doughs, and they're quite different even though they're both derived from wheat. The flour dough is just all-purpose flour and water-essentially a pasta dough. The gluten in the flour gives it resilience, so it can be rolled very thin or stretched without tearing, and it is easily pinched closed. It is sturdy enough to withstand pan-frying, deep-frying, and boiling. The dough remains opaque, and you may vary its color and flavor by adding egg yolk, curry powder, or puréed spinach or carrots.

The other basic dumpling dough is made with wheat starch and a bit of tapioca flour. This dough is more fragile and tender than flour dough, and it is prone to splitting open during steaming if it is not carefully pinched closed. Still, this is the dough that becomes a translucent jewel case when steamed, and its lightness will not overwhelm a delicate filling.

The wrappers carried by many supermarkets are made from flour dough, and though they may be labeled with different names, the primary difference is how thinly they are rolled. A one-pound package will contain about 20 spring roll wrappers, 40 to 60 potsticker wrappers, or at least 80 thinner siu mai wrappers. Square wonton wrappers are too thin to use in place of potsticker wrappers, but they work as siu mai wrappers; you may trim them into circles with a cookie cutter or use them as is.

A fanciful array of dumpling shapes and colors contributes as much to their appeal as the variety of fillings within. Traditionally, certain fillings go with certain folds; ha gow, for instance, are immediately recognizable by their shape. Still, I've had "ha gow" filled with pea shoots, so feel free to experiment with different combinations.

Once you have shaped and filled the dumplings, take care to pinch the edges together very tightly to seal in the filling and keep the dough from breaking open during cooking.

Wheat Starch Dough

When you want translucent steamed dumplings, this is the dough to use. Make fillings ahead so they can cool while you make the dough. Knead the dough as soon as you can handle it; the boiling water must reach every bit of starch. The dough cannot be made ahead and refrigerated, as it becomes more prone to splitting open during steaming. The dough will appear somewhat mottled and opaque when it is first removed from the steamer, but it becomes magically translucent as it cools.

Makes twenty-four 3 1/4-inch wrappers

1 1/4 cups wheat starch plus 1/4 cup tapioca flour, or 1 1/2 cups wheat starch

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 cup boiling water

1 teaspoon peanut or vegetable oil

In a medium bowl, combine the wheat starch, tapioca flour, if using, and salt. Add the boiling water and the oil and stir with chopsticks or a wooden spoon. While the dough is still very hot, turn it out onto a board dusted with 1 tablespoon of wheat starch. Knead until smooth, adding a little more wheat starch if necessary. The dough should be soft but not sticky.

Divide the dough into thirds. Use your palms to roll each portion into an 8-inch cylinder. Cover loosely with a slightly damp paper towel to keep the dough from drying out. The dough is now ready to cut and press or roll out as needed.

Note: You may use all wheat starch, but the addition of tapioca flour seems to help sealed edges stick together better. Tapioca flour is sometimes labeled tapioca starch.

To make round dumpling wrappers, wheat starch dough can be sandwiched between squares of baking parchment end then pressed flat using downward pressure on the flat side of a cleaver blade or the flat bottom of a pan. The result will be an almost-perfect circle. Afterward, if you still want your circles larger or a little thinner, roll them out lightly with a rolling pin before peeling away the parchment.

Flour Dough

These all-purpose flour-based wrappers are a dim sum staple. Although packaged potsticker wrappers and siu mai wrappers are easy to come by, homemade wrappers will be more elastic, with a bit more body, and the edges will not require moistening before sealing. Spinach, carrot, or curry add flavor and color for even greater versatility. The same dough, made with a bit less water and cut into large squares can be used for spring rolls.

Roll, shape, and fill one dumpling at a time until you are adept enough to work very quickly, because the rolled-out dough becomes overly elastic when it rests too long.

Makes twenty-four 3 1/4-inch wrappers

3/4 cup all-purpose flour, plus additional for dusting the board

To Make the filling

In a medium bowl, mix 3/4 cup flour with 1/3 cup water until combined. Turn out onto a generously floured board and knead for 3 to 4 minutes, or until smooth. The dough should be fairly stiff. Form the dough into a 9-inch cylinder. Then cut it in half crosswise. Dust the dough with flour, cover it loosely with plastic wrap, and let it rest at room temperature for 20 minutes.

On a lightly floured board, use your palms to roll each cylinder out to about 12 inches. The dough is now ready to cut and roll as needed. Keep the unused portion loosely covered with plastic wrap or an overturned bowl as you work to prevent it from drying out.

Unlike wheat starch dough, flour dough needs to be rolled out with a rolling pin. I think a slight variation in the circles is part of the charm of handmade dumplings, but for more uniform dumplings, you may use a cookie cutter to cut 3- to 31/4-inch circles out of rolled-out dough. A tuna or bamboo shoot can with both ends cut out makes a good 31/4-inch cutter.

Variations

Egg Dough

To make a slightly yellower dough, lightly beat 1 large egg yolk with enough water to make 1/3 cup. Mix with the flour and proceed as above.

Spinach Dough

This green dough works for steamed, boiled, and pan-fried dumplings, and its color contrasts beautifully with a variety of fillings, especially bright orange shrimp in siu mai.

Place 1 cup (2 ounce raw) packed spinach leaves (no stems) with 1 tablespoon water over low heat until just wilted. Without squeezing the spinach out, place it in a measuring cup with enough water to make 1/3 cup. Transfer to a blender and blend to a thick puree. Transfer the puree to a bowl, mix in 3/4 cup flour, and then turn the dough out onto a lightly floured board and knead it until the spinach is distributed throughout the dough. Proceed as on page 22.

Carrot Dough

Carrot dough is best for steamed or pan-fried dumplings; boiling, however, diffuses both its flavor and color.

Boil a peeled and chunked medium carrot for 8 minutes, or until soft. Weigh out 1 ounce carrot and add water to make 1/3 cup. Purèe in a blender until smooth. Transfer to a bowl, mix in 3/4 cup flour, and then turn the dough out onto a lightly floured board and knead it until the carrot is well blended in the dough. Proceed as on page 22.

Curry Dough

While curry dough is good for boiled and steamed dumplings, it's superb for potstickers because pan-frying enhances both the flavor and aroma of the curry. Stir 1 1/4 teaspoons curry powder into the flour before adding the water.

Legend has tea being discovered accidentally around 3000 b.c., when tea leaves blew into an outdoor cooking vessel being used to boil water. It was immediately appreciated for its refreshing flavor, and the eventual discovery of its medicinal value and ability to enhance alertness led to its increased use.

Tea was brewed from fresh leaves until the third century b.c., when drying and processing tremendously widened its popularity. Tea has been cultivated commercially in China for at least 1,800 years. Through the centuries, it has served as currency, as payment of taxes to emperors, and as a key factor in the development of porcelain, world trade, and international relations.

While the earliest teahouses served nothing but tea, that gradually changed. Starting with nuts and seeds, accompaniments became more and more elaborate, until "having tea" came to connote enjoying a meal at which dim sum played the central role.

Tea has evolved, too, into countless varieties, but every tea can still be classified as belonging to one of three categories: green, semi-fermented, or black (called red in China). All come from the same shrub, Camellia sinensis. Differences arise from processing techniques. Leaves for green tea are either wilted or not, then pan-fried, steamed, or fired in an oven to prevent oxidation and enzyme action. Leaves for semi-fermented and black teas are wilted, then bruised to allow oxidation to different degrees; this triggers enzymes to create chemical changes, producing tea with more color and less astringency. A final firing stops the process and dries the leaves.

Further variations in tea result from differing soils, climates, time of year the leaves are picked, which leaves are picked, whether leaves are wilted in the sun or shade, and whether flowers or other ingredients are added to scent the tea.

Choosing a Tea

The first question you will be asked when you are seated at a dim sum restaurant is, "What tea will you have?" Here are some favorites you may want to try, either at a restaurant or at home:

Dragon Well, or lung ching, is a mellow green tea celebrated for its bright color and cooling effect. The highest grade is picked from tiny, very young buds and leaves, then dried flat, and the skill required to process them contributes to its high cost.

Gunpowder, or pingshui, is a strong green tea named for the pelletlike shape of its tightly rolled leaves. It is also known as pearl tea, or zhucha, because of its appearance.

Jasmine, or moli huacha, is a green or semi-fermented oolong tea with jasmine flowers added. It is refreshingly astringent, with a delicate flower fragrance; the oolong variety is fuller, with a more lingering aftertaste. Jasmine is often the default tea you will be given if you don't make a choice.

Keemun, or qihong, is known as the king or champagne of black teas, for its roselike fragrance, slightly smoky taste, and deep amber color.

Lychee, or lizhi hongcha, is a black tea scented with the juice of lychee fruit, which also gives it a sweet, mellow, flowery aroma.

Oolong refers to a group of semi-fermented teas, less astringent than green teas, with a floral aftertaste. These include ti kwan yin and some jasmine teas.

Pu-erh (also pronounced po nay or bo lay), a semi-fermented tea, is a popular dim sum tea because of its reputed ability to counteract rich food and reduce cholesterol. This is the tea I order if I plan to indulge in deep-fried dim sum. It has an earthy, mellow flavor.

Ti Kwan Yin (also spelled tieguanyin), the Iron Goddess of Mercy, lends her name to this most famous oolong tea, prized for its orchidlike aroma.

Brewing Tea

There are many disagreements about how to brew perfect tea, with different opinions on correct water temperature, whether to use a tea ball or tea bags, how long to steep or infuse the tea, how much tea to use, and whether to reuse the leaves for a second pot. You will no doubt develop your own preferences, but for starters, here are some suggestions.

For the freshest-tasting tea, start with cold water in your kettle. While it is boiling, fill your teapot with hot water to warm it. Just before the water boils, empty the teapot and measure about 1 teaspoon of tea leaves into the pot for each cup of water you plan to use. If you use a perforated metal tea ball, do not overfill it, because the leaves need room to expand.

Pour the boiling water directly over the leaves and steep them for 3 to 5 minutes. (Some people first "wash" the dry tea leaves with a little boiling water, pouring it off immediately, then filling the pot with fresh boiling water.) Green teas require less steeping time than semi-fermented and black teas. Stronger tea is made by using more leaves, not more time. Longer steeping may result in bitter tea, so you may want to transfer the tea to another heated pot or, as many Chinese households do, to a heated thermos.

I don't mind a few tea leaves in the bottom of my cup, but if you're fussier, use a tea strainer when you pour your tea into the cup.

More boiling water may be added to the teapot for a second infusion. In fact, some connoisseurs insist the second infusion is best.

With a Chinese meal, whether to serve tea with or after the food is a regional preference, but tea is always served with dim sum. In any case, never add sugar, milk, or lemon to the tea.

Steamed Dumplings

When most people think of dim sum, they probably think of dumplings first. Coax a waitress to lift the lids from the stacked steamers on her cart and you'll be tantalized by translucent wheat starch dumplings with myriad fillings-delectable mouthfuls of pork, shrimp, scallops, or vegetables. Most dumplings are steamed, their wrappers cleverly twisted and pleated into fanciful shapes. The most common, ha gow, is instantly recognizable by its delicately pleated exterior. Siu mai shows off its filling above a ruffled collar. Other dumplings are folded into triangles, crescents, and twisted circles.

Setting up a Steamer

Most steamed dishes are cooked over rapidly boiling water; the plate of food is kept elevated on a stand above the water level. The pot must be large enough to allow steam to circulate around the plate, and the pot should have a tight-fitting lid. A wok with a high, domed lid or a wide pasta pot can work well as a steamer.

If you plan to steam a lot, invest in a multitiered metal or bamboo steamer from Chinatown. Aluminum or stainless steel steamers have a bottom section to hold water, two tiers with perforated bottoms for steam to circulate through, and a tight lid. Advantages of a metal steamer are that the bottom section can double as a pot, and it is the best choice for steaming buns.

Bamboo steamer baskets are meant to fit snugly over an open wok filled with boiling water. The bottom of each tier is made from bamboo slats; the sides are fashioned from several layers of split bamboo lashed together. The ingeniously woven top holds in steam remarkably well; it is used instead of a wok lid. Advantages of bamboo steamers are that they impart a wonderful, subtle scent; they work as well as metal steamers for steaming buns; and they are pretty enough to hang on the wall or double as baskets. They also seem to improve with age; mine have lasted many years.

To steam foods, add water to the pot or wok to a depth of about 1 1/2 to 2 inches. If you are using a steamer, fill the bottom section two-thirds full with water.

Bring the water to a boil. Place the pan or plate of food on the stand in a pot or wok and cover it with a lid. If using a steamer, place the plate of food on a tier and stack the steamer together. Steam the food over high heat. Replenish the pot with boiling water as necessary between batches, and check the water level from time to time for dishes that require long cooking times.

What's in a Dough?

Most of the dumplings in this book use one of two basic dumpling doughs, and they're quite different even though they're both derived from wheat. The flour dough is just all-purpose flour and water-essentially a pasta dough. The gluten in the flour gives it resilience, so it can be rolled very thin or stretched without tearing, and it is easily pinched closed. It is sturdy enough to withstand pan-frying, deep-frying, and boiling. The dough remains opaque, and you may vary its color and flavor by adding egg yolk, curry powder, or puréed spinach or carrots.

The other basic dumpling dough is made with wheat starch and a bit of tapioca flour. This dough is more fragile and tender than flour dough, and it is prone to splitting open during steaming if it is not carefully pinched closed. Still, this is the dough that becomes a translucent jewel case when steamed, and its lightness will not overwhelm a delicate filling.

The wrappers carried by many supermarkets are made from flour dough, and though they may be labeled with different names, the primary difference is how thinly they are rolled. A one-pound package will contain about 20 spring roll wrappers, 40 to 60 potsticker wrappers, or at least 80 thinner siu mai wrappers. Square wonton wrappers are too thin to use in place of potsticker wrappers, but they work as siu mai wrappers; you may trim them into circles with a cookie cutter or use them as is.

A fanciful array of dumpling shapes and colors contributes as much to their appeal as the variety of fillings within. Traditionally, certain fillings go with certain folds; ha gow, for instance, are immediately recognizable by their shape. Still, I've had "ha gow" filled with pea shoots, so feel free to experiment with different combinations.

Once you have shaped and filled the dumplings, take care to pinch the edges together very tightly to seal in the filling and keep the dough from breaking open during cooking.

Wheat Starch Dough

When you want translucent steamed dumplings, this is the dough to use. Make fillings ahead so they can cool while you make the dough. Knead the dough as soon as you can handle it; the boiling water must reach every bit of starch. The dough cannot be made ahead and refrigerated, as it becomes more prone to splitting open during steaming. The dough will appear somewhat mottled and opaque when it is first removed from the steamer, but it becomes magically translucent as it cools.

Makes twenty-four 3 1/4-inch wrappers

1 1/4 cups wheat starch plus 1/4 cup tapioca flour, or 1 1/2 cups wheat starch

1/2 teaspoon salt

1 cup boiling water

1 teaspoon peanut or vegetable oil

In a medium bowl, combine the wheat starch, tapioca flour, if using, and salt. Add the boiling water and the oil and stir with chopsticks or a wooden spoon. While the dough is still very hot, turn it out onto a board dusted with 1 tablespoon of wheat starch. Knead until smooth, adding a little more wheat starch if necessary. The dough should be soft but not sticky.

Divide the dough into thirds. Use your palms to roll each portion into an 8-inch cylinder. Cover loosely with a slightly damp paper towel to keep the dough from drying out. The dough is now ready to cut and press or roll out as needed.

Note: You may use all wheat starch, but the addition of tapioca flour seems to help sealed edges stick together better. Tapioca flour is sometimes labeled tapioca starch.

To make round dumpling wrappers, wheat starch dough can be sandwiched between squares of baking parchment end then pressed flat using downward pressure on the flat side of a cleaver blade or the flat bottom of a pan. The result will be an almost-perfect circle. Afterward, if you still want your circles larger or a little thinner, roll them out lightly with a rolling pin before peeling away the parchment.

Flour Dough

These all-purpose flour-based wrappers are a dim sum staple. Although packaged potsticker wrappers and siu mai wrappers are easy to come by, homemade wrappers will be more elastic, with a bit more body, and the edges will not require moistening before sealing. Spinach, carrot, or curry add flavor and color for even greater versatility. The same dough, made with a bit less water and cut into large squares can be used for spring rolls.

Roll, shape, and fill one dumpling at a time until you are adept enough to work very quickly, because the rolled-out dough becomes overly elastic when it rests too long.

Makes twenty-four 3 1/4-inch wrappers

3/4 cup all-purpose flour, plus additional for dusting the board

To Make the filling

In a medium bowl, mix 3/4 cup flour with 1/3 cup water until combined. Turn out onto a generously floured board and knead for 3 to 4 minutes, or until smooth. The dough should be fairly stiff. Form the dough into a 9-inch cylinder. Then cut it in half crosswise. Dust the dough with flour, cover it loosely with plastic wrap, and let it rest at room temperature for 20 minutes.

On a lightly floured board, use your palms to roll each cylinder out to about 12 inches. The dough is now ready to cut and roll as needed. Keep the unused portion loosely covered with plastic wrap or an overturned bowl as you work to prevent it from drying out.

Unlike wheat starch dough, flour dough needs to be rolled out with a rolling pin. I think a slight variation in the circles is part of the charm of handmade dumplings, but for more uniform dumplings, you may use a cookie cutter to cut 3- to 31/4-inch circles out of rolled-out dough. A tuna or bamboo shoot can with both ends cut out makes a good 31/4-inch cutter.

Variations

Egg Dough

To make a slightly yellower dough, lightly beat 1 large egg yolk with enough water to make 1/3 cup. Mix with the flour and proceed as above.

Spinach Dough

This green dough works for steamed, boiled, and pan-fried dumplings, and its color contrasts beautifully with a variety of fillings, especially bright orange shrimp in siu mai.

Place 1 cup (2 ounce raw) packed spinach leaves (no stems) with 1 tablespoon water over low heat until just wilted. Without squeezing the spinach out, place it in a measuring cup with enough water to make 1/3 cup. Transfer to a blender and blend to a thick puree. Transfer the puree to a bowl, mix in 3/4 cup flour, and then turn the dough out onto a lightly floured board and knead it until the spinach is distributed throughout the dough. Proceed as on page 22.

Carrot Dough

Carrot dough is best for steamed or pan-fried dumplings; boiling, however, diffuses both its flavor and color.

Boil a peeled and chunked medium carrot for 8 minutes, or until soft. Weigh out 1 ounce carrot and add water to make 1/3 cup. Purèe in a blender until smooth. Transfer to a bowl, mix in 3/4 cup flour, and then turn the dough out onto a lightly floured board and knead it until the carrot is well blended in the dough. Proceed as on page 22.

Curry Dough

While curry dough is good for boiled and steamed dumplings, it's superb for potstickers because pan-frying enhances both the flavor and aroma of the curry. Stir 1 1/4 teaspoons curry powder into the flour before adding the water.