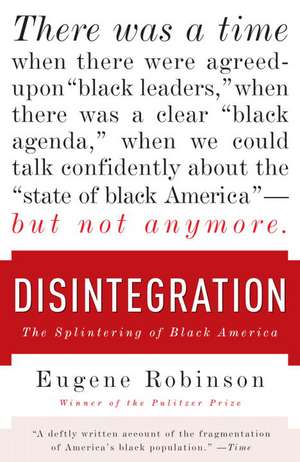

Disintegration: The Splintering of Black America

Autor Eugene Robinsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2011

The African American population in the United States has always been seen as a single entity: a “Black America” with unified interests and needs. In his groundbreaking book, Disintegration, Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist Eugene Robinson argues that over decades of desegregation, affirmative action, and immigration, the concept of Black America has shattered. Instead of one black America, now there are four:

• a Mainstream middle-class majority with a full ownership stake in American society;

• a large, Abandoned minority with less hope of escaping poverty and dysfunction than at any time since Reconstruction’s crushing end;

• a small Transcendent elite with such enormous wealth, power, and influence that even white folks have to genuflect;

• and two newly Emergent groups—individuals of mixed-race heritage and communities of recent black immigrants—that make us wonder what “black” is even supposed to mean.

Robinson shows that the four black Americas are increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mindsets, different hopes, fears, and dreams. What’s more, these groups have become so distinct that they view each other with mistrust and apprehension. And yet all are reluctant to acknowledge division.

Disintegration offers a new paradigm for understanding race in America, with implications both hopeful and dispiriting. It shines necessary light on debates about affirmative action, racial identity, and the ultimate question of whether the black community will endure.

Preț: 93.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 140

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.83€ • 18.37$ • 14.94£

17.83€ • 18.37$ • 14.94£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767929967

ISBN-10: 0767929969

Pagini: 254

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0767929969

Pagini: 254

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Extras

1

“BLACK AMERICA” DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE

It was one of those only-in-Washington affairs, a glittering A-list dinner in a stately mansion near Embassy Row. The hosts were one of the capital’s leading power couples—the husband a wealthy attorney who famously served as consigliere and golfing partner to presidents, the wife a social doyenne who sat on all the right committees and boards. The guest list included enough bold-faced names to fill the Washington Post’s Reliable Source gossip column for a solid week. Most of the furniture had been cleared away to let people circulate, but the elegant rooms were so thick with status, ego, and ambition that it was hard to move.

Officially the dinner was to honor an aging lion of American business: the retired chief executive of the world’s biggest media and entertainment company. Owing to recent events, however, the distinguished mogul was eclipsed at his own party. An elegant businesswoman from Chicago—a stranger to most of the other guests—suddenly had become one of the capital’s most important power brokers, and this exclusive soiree was serving as her unofficial debut in Washington society. The bold-faced names feigned nonchalance but were desperate to meet her. Eyes followed the woman's every move; ears strained to catch her every word. She pretended not to mind being stalked from room to room by eager supplicants and would-be best friends. As the evening went on, it became apparent that while the other guests were taking her measure, she was systematically taking theirs. To every beaming, glad-handing, air-kissing approach she responded with the Mona Lisa smile of a woman not to be taken lightly.

Others there that night included a well-connected lawyer who would soon be nominated to fill a key cabinet post; the chief executive of one of the nation’s leading cable-television networks; the former chief executive of the mortgage industry’s biggest firm; a gaggle of high-powered lawyers; a pride of investment bankers; a flight of social butterflies; and a chattering of well-known cable-television pundits, slightly hoarse and completely exhausted after spending a full year in more or less continuous yakety-yak about the presidential race. By any measure, it was a top-shelf crowd.

On any given night, of course, some gathering of the great and the good in Washington ranks above all others by virtue of exclusivity, glamour, or the number of Secret Service SUVs parked outside. What makes this one worth noting is that all the luminaries I have described are black.

The affair was held at the home of Vernon Jordan, the smooth, handsome, charismatic confidant of Democratic presidents, and his wife, Ann, an emeritus trustee of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and a reliable presence at every significant social event in town. Known for his impeccable political instincts, Jordan had made the rare mistake of backing the wrong candidate in the 2008 primaries—his friend Hillary Clinton. There are no grudges in Vernon's world, however; barely a week after the election, he was already skillfully renewing his ties with the Obama crowd.

The nominal guest of honor was Richard Parsons, the former CEO of Time Warner Inc. Months earlier, he had relinquished his corner office on Columbus Circle to tend the Tuscan vineyard that friends said was the favorite of his residences.

The woman who stole the show was Valerie Jarrett, one of Obama’s best friends and most trusted advisers. A powerful figure in the Chicago business community, Jarrett was unknown in Washington until Obama made his out-of-nowhere run to capture the Democratic nomination and then the presidency. Suddenly she was the most talked-about and sought- after woman in town. Everyone understood that she would be sitting on the mother lode of the capital’s rarest and most precious asset: access to the president of the United States.

Others sidling up to the buffet included Eric Holder, soon to be nominated as the nation's first black attorney general, and his wife, Sharon Malone, a prominent obstetrician; Debra Lee, the longtime chief of Black Entertainment Television and one of the most powerful women in the entertainment industry; Franklin Raines, the former CEO of Fannie Mae, a central and controversial figure in the financial crisis that had begun to roil markets around the globe; and cable-news regulars Donna Brazile and Soledad O’Brien from CNN, Juan Williams from Fox News Channel, and, well, me from MSNBC—all of us having talked so much during the long campaign that we were sick of hearing our own voices.

The glittering scene wasn’t at all what most people have in mind when they talk about black America-which is one reason why so much of what people say about black America makes so little sense. The fact is that asking what something called "black America" thinks, feels, or wants makes as much sense as commissioning a new Gallup poll of the Ottoman Empire. Black America, as we knew it, is history.

***

There was a time when there were agreed-upon "black leaders," when there was a clear "black agenda," when we could talk confidently about "the state of black America"-but not anymore. Not after decades of desegregation, affirmative action, and urban decay; not after globalization decimated the working class and trickle-down economics sorted the nation into winners and losers; not after the biggest wave of black immigration from Africa and the Caribbean since slavery; not after most people ceased to notice—much less care—when a black man and a white woman walked down the street hand in hand. These are among the forces and trends that have had the unintended consequence of tearing black America to pieces.

Ever wonder why black elected officials spend so much time talking about purely symbolic "issues," like an official apology for slavery? Or why they never miss the chance to denounce a racist outburst from a rehab-bound celebrity? It's because symbolism, history, and old- fashioned racism are about the only things they can be sure their African American constituents still have in common.

Barack Obama’s stunning election as the first African American president seemed to come out of nowhere, but it was the result of a transformation that has been unfolding for decades. With implications both hopeful and dispiriting, black America has undergone a process of disintegration.

Disintegration isn’t something black America likes to talk about. But it's right there, documented in census data, economic reports, housing patterns, and a wealth of other evidence just begging for honest analysis. And it's right there in our daily lives, if we allow ourselves to notice. Instead of one black America, now there are four:

* a Mainstream middle-class majority with a full ownership stake in American society

* a large, Abandoned minority with less hope of escaping poverty and dysfunction than at any time since Reconstruction's crushing end

* a small Transcendent elite with such enormous wealth, power, and influence that even white folks have to genuflect

* two newly Emergent groups-individuals of mixed-race heritage and communities of recent black immigrants-that make us wonder what "black" is even supposed to mean

These four black Americas are increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mind-sets, different hopes, fears, and dreams. There are times and places where we all still come back together—on the increasingly rare occasions when we feel lumped together, defined, and threatened solely on the basis of skin color, usually involving some high-profile instance of bald-faced discrimination or injustice; and in venues like "urban" or black-oriented radio, which serves as a kind of speed-of-light grapevine. More and more, however, we lead separate lives.

And where these distinct "nations" rub against one another, there are sparks. The Mainstream tend to doubt the authenticity of the Emergent, but they’re usually too polite, or too politically correct, to say so out loud. The Abandoned accuse the Emergent—the immigrant segment, at least—of moving into Abandoned neighborhoods and using the locals as mere stepping-stones. The immigrant Emergent, with their intact families and long-range mind-set, ridicule the Abandoned for being their own worst enemies. The Mainstream bemoan the plight of the Abandoned—but express their deep concern from a distance. The Transcendent, to steal the old line about Boston society, speak only to God; they are idolized by the Mainstream and the Emergent for the obstacles they have overcome, and by the Abandoned for the shiny things they own. Mainstream, Emergent, and Transcendent all lock their car doors when they drive through an Abandoned neighborhood. They think the Abandoned don't hear the disrespectful thunk of the locks; they're wrong.

How did this breakup happen? It’s overly simplistic to draw a straight line from "We Shall Overcome" to "Get Rich or Die Tryin’," but that's the general trajectory.

Forty years ago, after major cities from coast to coast had gone up in flames, black equaled poor. Roughly six in ten black Americans were barely a step ahead of the bill collector, with fully 40 percent of the total living in the abject penury that the Census Bureau officially labels "poverty" and another 20 percent earning a bit more but still basically poor. Over the next three decades—as civil rights laws banned discrimination in education, housing, and employment, and as affirmative action offered life-changing opportunities to those prepared to take advantage—millions of black households clawed their way into the Mainstream and the black poverty rate fell steadily, year after year. By the mid-'90s, it was down to 25 percent—and then the needle got stuck. Today, roughly one-quarter of black Americans-the Abandoned-remain in poverty.(1)

And the poorest of these poor folks are actually losing ground. In 2000, 14.9 percent of black households reported income of less than $10,000 (in today's dollars); in 2005, the figure was 17.1 percent.(2) Demographically, the Abandoned constitute the youngest black America; they are also by far the least suburban, living for the most part in core urban neighborhoods and the rural South.

Those who made it into the Mainstream, however, have continued their rise. In 1967, only one black household in ten made $50,000 a year; now three of every ten black families earn at least that much. More strikingly, four decades ago not even two black households in a hundredearned the equivalent of more than $100,000 a year. Now almost one black household in ten has crossed that threshold to the upper middle class—joining George and Louise Jefferson in that "dee-luxe apartment in the sky," perhaps, or living down the street from the Huxtables’ handsomely appointed brownstone. All told, the four black Americas control an estimated $800 billion in purchasing power—roughly the GDP of the thirteenth-richest nation on earth. Most of that money is made and spent by the Mainstream.(3)

Here’s another way to look at it: Forty years ago, if you found yourself among a representative all-black crowd, you could assume that nearly half the people around you were poor, poorly educated, and underemployed. Today, if you found yourself at a representative gathering of black adults, four out of five would be solidly middle class.

And some African Americans have soared far higher. A friend of mine who lives in Chicago once took a flight on the Tribune Company's corporate jet. Noticing a much larger, newer, fancier private jet parked on the tarmac nearby, he asked his boss whose it was. The answer: "Oprah’s." The all-powerful Winfrey is one of the African Americans who have soared highest of all, into the realm of the Transcendent. There have long been black millionaires—Madam C. J. Walker, who built an empire on hair-care products in the early twentieth century, is often cited as the first. But never before have African Americans presided as full-fledged Masters of the Universe over some of the biggest firms on Wall Street (Richard Parsons, Kenneth Chenault, Stanley O’Neal). There have been wealthy black athletes since Jack Johnson, but never before have they transformed themselves into such savvy tycoons (Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods). And while African Americans have made billions for the music industry over the years, even pioneers such as Berry Gordy Jr. and Quincy Jones never owned and controlled as big a chunk of the business as today’s hip-hop moguls (Russell Simmons, P. Diddy, Jay-Z).

And the Emergent? They’re the product of two separate phenomena. First, there has been a flood of black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. In 1980, the census reported 816,000 foreign-born black people in the United States; by the 2000 census, that figure had more than tripled to 2,815,000.(4) You might question my use of the word "flood" for numbers that seem relatively small in absolute terms, but consider these newcomers’ outsize impact: Half or more of the black students entering elite universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Duke these days are the sons and daughters of African immigrants.(5) This makes sense when you consider that their parents are the best- educated immigrant group in America, with more advanced degrees than the Asians, the Europeans, you name it. (They’re far better educated than native-born Americans, black or white.) But their children's educational success leads Mainstream and Abandoned black Americans to ask whether affirmative action and other programs designed to foster diversity are reaching the people they were intended to help—the systematically disadvantaged descendants of slaves.

The second Emergent phenomenon is the acceptance of interracial marriage, once a crime and until recently a novelty. A University of Michigan study found that in 1990, nearly one married black man in ten was wed to a white woman-and roughly one married black woman in twenty-five was wed to a white man. These figures, the researchers found, had increased eightfold over the previous four decades.(6) Barack Obama, the man who would be president; Adrian Fenty, the mayor of Washington, D.C.; Jordin Sparks, a winner on American Idol—all are the product of black-white marriages. And the boomer-echo generation, raised on a diet of diversity, has even fewer hang-ups about race and relationships.

In a sense, though, we’re just headed back to the future. Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. recently produced a public-television series in which he used genealogical research and DNA testing to unearth the heritage of several prominent African Americans. When he sent his own blood off to be tested, Gates discovered to his surprise that more than 50 percent of his genetic material was European. Wider DNA testing has shown that nearly one-third of all African Americans trace their heritage to a white male ancestor—likely a slave owner.

So forget about whether the mixed-race Emergents are "black enough." How black am I? How black can any of us claim to be?

So forget about whether the mixed-race Emergents are "black enough." How black am I? How black can any of us claim to be?

“BLACK AMERICA” DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE

It was one of those only-in-Washington affairs, a glittering A-list dinner in a stately mansion near Embassy Row. The hosts were one of the capital’s leading power couples—the husband a wealthy attorney who famously served as consigliere and golfing partner to presidents, the wife a social doyenne who sat on all the right committees and boards. The guest list included enough bold-faced names to fill the Washington Post’s Reliable Source gossip column for a solid week. Most of the furniture had been cleared away to let people circulate, but the elegant rooms were so thick with status, ego, and ambition that it was hard to move.

Officially the dinner was to honor an aging lion of American business: the retired chief executive of the world’s biggest media and entertainment company. Owing to recent events, however, the distinguished mogul was eclipsed at his own party. An elegant businesswoman from Chicago—a stranger to most of the other guests—suddenly had become one of the capital’s most important power brokers, and this exclusive soiree was serving as her unofficial debut in Washington society. The bold-faced names feigned nonchalance but were desperate to meet her. Eyes followed the woman's every move; ears strained to catch her every word. She pretended not to mind being stalked from room to room by eager supplicants and would-be best friends. As the evening went on, it became apparent that while the other guests were taking her measure, she was systematically taking theirs. To every beaming, glad-handing, air-kissing approach she responded with the Mona Lisa smile of a woman not to be taken lightly.

Others there that night included a well-connected lawyer who would soon be nominated to fill a key cabinet post; the chief executive of one of the nation’s leading cable-television networks; the former chief executive of the mortgage industry’s biggest firm; a gaggle of high-powered lawyers; a pride of investment bankers; a flight of social butterflies; and a chattering of well-known cable-television pundits, slightly hoarse and completely exhausted after spending a full year in more or less continuous yakety-yak about the presidential race. By any measure, it was a top-shelf crowd.

On any given night, of course, some gathering of the great and the good in Washington ranks above all others by virtue of exclusivity, glamour, or the number of Secret Service SUVs parked outside. What makes this one worth noting is that all the luminaries I have described are black.

The affair was held at the home of Vernon Jordan, the smooth, handsome, charismatic confidant of Democratic presidents, and his wife, Ann, an emeritus trustee of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and a reliable presence at every significant social event in town. Known for his impeccable political instincts, Jordan had made the rare mistake of backing the wrong candidate in the 2008 primaries—his friend Hillary Clinton. There are no grudges in Vernon's world, however; barely a week after the election, he was already skillfully renewing his ties with the Obama crowd.

The nominal guest of honor was Richard Parsons, the former CEO of Time Warner Inc. Months earlier, he had relinquished his corner office on Columbus Circle to tend the Tuscan vineyard that friends said was the favorite of his residences.

The woman who stole the show was Valerie Jarrett, one of Obama’s best friends and most trusted advisers. A powerful figure in the Chicago business community, Jarrett was unknown in Washington until Obama made his out-of-nowhere run to capture the Democratic nomination and then the presidency. Suddenly she was the most talked-about and sought- after woman in town. Everyone understood that she would be sitting on the mother lode of the capital’s rarest and most precious asset: access to the president of the United States.

Others sidling up to the buffet included Eric Holder, soon to be nominated as the nation's first black attorney general, and his wife, Sharon Malone, a prominent obstetrician; Debra Lee, the longtime chief of Black Entertainment Television and one of the most powerful women in the entertainment industry; Franklin Raines, the former CEO of Fannie Mae, a central and controversial figure in the financial crisis that had begun to roil markets around the globe; and cable-news regulars Donna Brazile and Soledad O’Brien from CNN, Juan Williams from Fox News Channel, and, well, me from MSNBC—all of us having talked so much during the long campaign that we were sick of hearing our own voices.

The glittering scene wasn’t at all what most people have in mind when they talk about black America-which is one reason why so much of what people say about black America makes so little sense. The fact is that asking what something called "black America" thinks, feels, or wants makes as much sense as commissioning a new Gallup poll of the Ottoman Empire. Black America, as we knew it, is history.

***

There was a time when there were agreed-upon "black leaders," when there was a clear "black agenda," when we could talk confidently about "the state of black America"-but not anymore. Not after decades of desegregation, affirmative action, and urban decay; not after globalization decimated the working class and trickle-down economics sorted the nation into winners and losers; not after the biggest wave of black immigration from Africa and the Caribbean since slavery; not after most people ceased to notice—much less care—when a black man and a white woman walked down the street hand in hand. These are among the forces and trends that have had the unintended consequence of tearing black America to pieces.

Ever wonder why black elected officials spend so much time talking about purely symbolic "issues," like an official apology for slavery? Or why they never miss the chance to denounce a racist outburst from a rehab-bound celebrity? It's because symbolism, history, and old- fashioned racism are about the only things they can be sure their African American constituents still have in common.

Barack Obama’s stunning election as the first African American president seemed to come out of nowhere, but it was the result of a transformation that has been unfolding for decades. With implications both hopeful and dispiriting, black America has undergone a process of disintegration.

Disintegration isn’t something black America likes to talk about. But it's right there, documented in census data, economic reports, housing patterns, and a wealth of other evidence just begging for honest analysis. And it's right there in our daily lives, if we allow ourselves to notice. Instead of one black America, now there are four:

* a Mainstream middle-class majority with a full ownership stake in American society

* a large, Abandoned minority with less hope of escaping poverty and dysfunction than at any time since Reconstruction's crushing end

* a small Transcendent elite with such enormous wealth, power, and influence that even white folks have to genuflect

* two newly Emergent groups-individuals of mixed-race heritage and communities of recent black immigrants-that make us wonder what "black" is even supposed to mean

These four black Americas are increasingly distinct, separated by demography, geography, and psychology. They have different profiles, different mind-sets, different hopes, fears, and dreams. There are times and places where we all still come back together—on the increasingly rare occasions when we feel lumped together, defined, and threatened solely on the basis of skin color, usually involving some high-profile instance of bald-faced discrimination or injustice; and in venues like "urban" or black-oriented radio, which serves as a kind of speed-of-light grapevine. More and more, however, we lead separate lives.

And where these distinct "nations" rub against one another, there are sparks. The Mainstream tend to doubt the authenticity of the Emergent, but they’re usually too polite, or too politically correct, to say so out loud. The Abandoned accuse the Emergent—the immigrant segment, at least—of moving into Abandoned neighborhoods and using the locals as mere stepping-stones. The immigrant Emergent, with their intact families and long-range mind-set, ridicule the Abandoned for being their own worst enemies. The Mainstream bemoan the plight of the Abandoned—but express their deep concern from a distance. The Transcendent, to steal the old line about Boston society, speak only to God; they are idolized by the Mainstream and the Emergent for the obstacles they have overcome, and by the Abandoned for the shiny things they own. Mainstream, Emergent, and Transcendent all lock their car doors when they drive through an Abandoned neighborhood. They think the Abandoned don't hear the disrespectful thunk of the locks; they're wrong.

How did this breakup happen? It’s overly simplistic to draw a straight line from "We Shall Overcome" to "Get Rich or Die Tryin’," but that's the general trajectory.

Forty years ago, after major cities from coast to coast had gone up in flames, black equaled poor. Roughly six in ten black Americans were barely a step ahead of the bill collector, with fully 40 percent of the total living in the abject penury that the Census Bureau officially labels "poverty" and another 20 percent earning a bit more but still basically poor. Over the next three decades—as civil rights laws banned discrimination in education, housing, and employment, and as affirmative action offered life-changing opportunities to those prepared to take advantage—millions of black households clawed their way into the Mainstream and the black poverty rate fell steadily, year after year. By the mid-'90s, it was down to 25 percent—and then the needle got stuck. Today, roughly one-quarter of black Americans-the Abandoned-remain in poverty.(1)

And the poorest of these poor folks are actually losing ground. In 2000, 14.9 percent of black households reported income of less than $10,000 (in today's dollars); in 2005, the figure was 17.1 percent.(2) Demographically, the Abandoned constitute the youngest black America; they are also by far the least suburban, living for the most part in core urban neighborhoods and the rural South.

Those who made it into the Mainstream, however, have continued their rise. In 1967, only one black household in ten made $50,000 a year; now three of every ten black families earn at least that much. More strikingly, four decades ago not even two black households in a hundredearned the equivalent of more than $100,000 a year. Now almost one black household in ten has crossed that threshold to the upper middle class—joining George and Louise Jefferson in that "dee-luxe apartment in the sky," perhaps, or living down the street from the Huxtables’ handsomely appointed brownstone. All told, the four black Americas control an estimated $800 billion in purchasing power—roughly the GDP of the thirteenth-richest nation on earth. Most of that money is made and spent by the Mainstream.(3)

Here’s another way to look at it: Forty years ago, if you found yourself among a representative all-black crowd, you could assume that nearly half the people around you were poor, poorly educated, and underemployed. Today, if you found yourself at a representative gathering of black adults, four out of five would be solidly middle class.

And some African Americans have soared far higher. A friend of mine who lives in Chicago once took a flight on the Tribune Company's corporate jet. Noticing a much larger, newer, fancier private jet parked on the tarmac nearby, he asked his boss whose it was. The answer: "Oprah’s." The all-powerful Winfrey is one of the African Americans who have soared highest of all, into the realm of the Transcendent. There have long been black millionaires—Madam C. J. Walker, who built an empire on hair-care products in the early twentieth century, is often cited as the first. But never before have African Americans presided as full-fledged Masters of the Universe over some of the biggest firms on Wall Street (Richard Parsons, Kenneth Chenault, Stanley O’Neal). There have been wealthy black athletes since Jack Johnson, but never before have they transformed themselves into such savvy tycoons (Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods). And while African Americans have made billions for the music industry over the years, even pioneers such as Berry Gordy Jr. and Quincy Jones never owned and controlled as big a chunk of the business as today’s hip-hop moguls (Russell Simmons, P. Diddy, Jay-Z).

And the Emergent? They’re the product of two separate phenomena. First, there has been a flood of black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean. In 1980, the census reported 816,000 foreign-born black people in the United States; by the 2000 census, that figure had more than tripled to 2,815,000.(4) You might question my use of the word "flood" for numbers that seem relatively small in absolute terms, but consider these newcomers’ outsize impact: Half or more of the black students entering elite universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Duke these days are the sons and daughters of African immigrants.(5) This makes sense when you consider that their parents are the best- educated immigrant group in America, with more advanced degrees than the Asians, the Europeans, you name it. (They’re far better educated than native-born Americans, black or white.) But their children's educational success leads Mainstream and Abandoned black Americans to ask whether affirmative action and other programs designed to foster diversity are reaching the people they were intended to help—the systematically disadvantaged descendants of slaves.

The second Emergent phenomenon is the acceptance of interracial marriage, once a crime and until recently a novelty. A University of Michigan study found that in 1990, nearly one married black man in ten was wed to a white woman-and roughly one married black woman in twenty-five was wed to a white man. These figures, the researchers found, had increased eightfold over the previous four decades.(6) Barack Obama, the man who would be president; Adrian Fenty, the mayor of Washington, D.C.; Jordin Sparks, a winner on American Idol—all are the product of black-white marriages. And the boomer-echo generation, raised on a diet of diversity, has even fewer hang-ups about race and relationships.

In a sense, though, we’re just headed back to the future. Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. recently produced a public-television series in which he used genealogical research and DNA testing to unearth the heritage of several prominent African Americans. When he sent his own blood off to be tested, Gates discovered to his surprise that more than 50 percent of his genetic material was European. Wider DNA testing has shown that nearly one-third of all African Americans trace their heritage to a white male ancestor—likely a slave owner.

So forget about whether the mixed-race Emergents are "black enough." How black am I? How black can any of us claim to be?

So forget about whether the mixed-race Emergents are "black enough." How black am I? How black can any of us claim to be?

Notă biografică

EUGENE ROBINSON joined the Washington Post in 1980, where he has served as London bureau chief, foreign editor, and, currently, associate editor and columnist. He was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, and in 2009, Robinson was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished commentary. Disintegration is his third book.

Recenzii

“A deftly written account of the fragmentation of America’s black population.” —Time

“[A] sober, careful and engaging consideration of phenomena that began with the official end of segregation and has of late been accelerating. . . . Those familiar with [Robinson’s] style will find Disintegration the same blend of logical analysis and gentle humor that makes him sometimes appear to be the Most Reasonable Man in America.” —SF Gate

“[A] bold call to action . . . [Disintegration] makes clear that Robinson’s success, and the success of his fellow black fortunates, simply do not negate the problems of the other 30% of blacks who continue to struggle at the bottom.” —Los Angeles Times

“The text would be useful as a young person’s introduction to Race in America 101.” —The New Republic

“Readers don’t have to agree with Robinson’s observations to appreciate the undeniable differences within black America and to maybe want further analysis.” —Booklist

“In this clear-eyed and compassionate study, Robinson . . . marshals persuasive evidence that the African-American population has splintered into four distinct and increasingly disconnected entities. . . . Of particular interest is the discussion of how immigrants from Africa, the ‘best-educated group coming to live in the United States,’ are changing what being black means.” —Publishers Weekly

"In Disintegration, Eugene Robinson neatly explodes decades' worth of lazy generalizations about race in America. At the same time, he raises new questions about community, invisibility, and the virtues and drawbacks of assimilation. An important book." —Gwen Ifill

"Gene Robinson's Disintegration is the first popular salvo in the Age of Obama regarding the delicate issues of class division, generation gap, and elite obsession in Black America. This painful conversation must continue--and we have Gene Robinson as a useful guide." —Cornel West

“[A] sober, careful and engaging consideration of phenomena that began with the official end of segregation and has of late been accelerating. . . . Those familiar with [Robinson’s] style will find Disintegration the same blend of logical analysis and gentle humor that makes him sometimes appear to be the Most Reasonable Man in America.” —SF Gate

“[A] bold call to action . . . [Disintegration] makes clear that Robinson’s success, and the success of his fellow black fortunates, simply do not negate the problems of the other 30% of blacks who continue to struggle at the bottom.” —Los Angeles Times

“The text would be useful as a young person’s introduction to Race in America 101.” —The New Republic

“Readers don’t have to agree with Robinson’s observations to appreciate the undeniable differences within black America and to maybe want further analysis.” —Booklist

“In this clear-eyed and compassionate study, Robinson . . . marshals persuasive evidence that the African-American population has splintered into four distinct and increasingly disconnected entities. . . . Of particular interest is the discussion of how immigrants from Africa, the ‘best-educated group coming to live in the United States,’ are changing what being black means.” —Publishers Weekly

"In Disintegration, Eugene Robinson neatly explodes decades' worth of lazy generalizations about race in America. At the same time, he raises new questions about community, invisibility, and the virtues and drawbacks of assimilation. An important book." —Gwen Ifill

"Gene Robinson's Disintegration is the first popular salvo in the Age of Obama regarding the delicate issues of class division, generation gap, and elite obsession in Black America. This painful conversation must continue--and we have Gene Robinson as a useful guide." —Cornel West