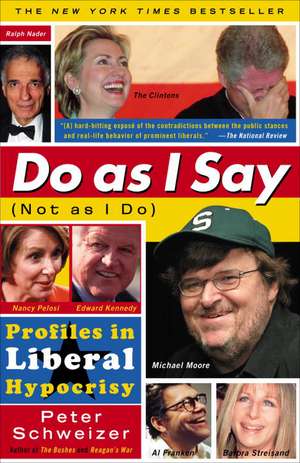

Do as I Say (Not as I Do): Profiles in Liberal Hypocrisy

Autor Peter Schweizeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

Members of the liberal left exude an air of moral certitude. They pride themselves on being selflessly committed to the highest ideals and seem particularly confident of the purity of their motives and the evil nature of their opponents. To correct economic and social injustice, liberals support a whole litany of policies and principles: progressive taxes, affirmative action, greater regulation of corporations, raising the inheritance tax, strict environmental regulations, children’s rights, consumer rights, and much, much more.

But do they actually live by these beliefs? Peter Schweizer decided to investigate in depth the private lives of some prominent liberals: politicians like the Clintons, Nancy Pelosi, the Kennedys, and Ralph Nader; commentators like Michael Moore, Al Franken, Noam Chomsky, and Cornel West; entertainers and philanthropists like Barbra Streisand and George Soros. Using everything from real estate transactions, IRS records, court depositions, and their own public statements, he sought to examine whether they really live by the principles they so confidently advocate.

What he found was a long list of glaring contradictions. Michael Moore denounces oil and defense contractors as war profiteers. He also claims to have no stock portfolio, yet he owns shares in Halliburton, Boeing, and Honeywell and does his postproduction film work in Canada to avoid paying union wages in the United States. Noam Chomsky opposes the very concept of private property and calls the Pentagon “the worst institution in human history,” yet he and his wife have made millions of dollars in contract work for the Department of Defense and own two luxurious homes. Barbra Streisand prides herself as an environmental activist, yet she owns shares in a notorious strip-mining company. Hillary Clinton supports the right of thirteen-year-old girls to have abortions without parental consent, yet she forbade thirteen-year-old Chelsea to pierce her ears and enrolled her in a school that would not distribute condoms to minors. Nancy Pelosi received the 2002 Cesar Chavez Award from the United Farm Workers, yet she and her husband own a Napa Valley vineyard that uses nonunion labor.

Schweizer’s conclusion is simple: liberalism in the end forces its adherents to become hypocrites. They adopt one pose in public, but when it comes to what matters most in their own lives—their property, their privacy, and their children—they jettison their liberal principles and embrace conservative ones. Schweizer thus exposes the contradiction at the core of liberalism: if these ideas don’t work for the very individuals who promote them, how can they work for the rest of us?

Preț: 93.81 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 141

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.95€ • 18.79$ • 14.94£

17.95€ • 18.79$ • 14.94£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Livrare express 22-28 februarie pentru 18.21 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767919029

ISBN-10: 0767919025

Pagini: 258

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767919025

Pagini: 258

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

“A spirited attack on lefty icons.” —New York Times

“An entertaining exposure . . . In a series of 11 profiles on leftist icons from Noam Chomsky and Al Franken to Hillary Clinton and Ted Kennedy, Schweizer reveals that the most vocal liberals do not practice what they preach.”

—The Weekly Standard

“An entertaining exposure . . . In a series of 11 profiles on leftist icons from Noam Chomsky and Al Franken to Hillary Clinton and Ted Kennedy, Schweizer reveals that the most vocal liberals do not practice what they preach.”

—The Weekly Standard

Notă biografică

PETER SCHWEIZER is a fellow at the Hoover Institution and the author of several books, including Reagan’s War and The Bushes. He lives in Florida with his wife and their two children.

Extras

NOAM CHOMSKY

Social Parasite, Economic

Protectionist, Amoral Defense

Contractor

I never thought a self–described socialist dissident and anti–imperialist crusader could be so thin–skinned.

I had sent Noam Chomsky several e-mails, questioning him in a mild but insistent way about his personal wealth, investments, and legal maneuvers to avoid paying taxes. What I got back was a stream of invective and some of the most creative logic I have ever seen in my life. No wonder he is considered one of the most important linguists in the world; he's adept at twisting words.

Noam Chomsky doesn't look like your typical revolutionary. The soft-spoken MIT professor is thin and poorly dressed, with a shy smile and gentle manner. But when he speaks or writes about America, the Pentagon, and capitalism, this self-appointed “champion of the ordinary guy” erupts as if the wrath of God had descended from heaven.

Chomsky doesn't think America is a free country: “The American electoral system is a series of four-year dictatorships.” There is no real free press, only “brainwashing under freedom.” In his book What Uncle Sam Really Wants, he describes an America on par with Nazi Germany. “Legally speaking,” he says, “there's a very solid case for impeaching every American president since the Second World War. They've all been either outright war criminals or involved in serious war crimes.” His views on capitalism? Put it up there with Nazism. Don't even ask about the Pentagon. It's the most vile institution on the face of the earth.

Chomsky may sound like a crank, but he’s a crank taken seriously around the world. Hundreds of thousands of college students read his books. Michael Moore has claimed him as a mentor of sorts, and the leadership of the AFL-CIO has gone to him for political advice. The Guardian declares that he “ranks with Marx, Shakespeare, and the Bible as one of the most quoted sources in the humanities.” Robert Barsky, in a glowing biography, claims that Chomsky “will be for future generations what Galileo, Descartes, Newton, Mozart or Picasso have been for ours.”(1)

Though he originally made his name as a professor of linguistics, his political radicalism has made him a superstar. He is embraced by entertainers and actors as some kind of modern-day Buddha. Bono, of the band U2, calls him “the Elvis of Academia.” On Saturday Night Live, a cast member carried a copy of his collected works during one skit in obvious homage to him. In the film Good Will Hunting, Matt Damon played a brilliant young man who quotes Chomsky like some Old Testament prophet. The rock band Pearl Jam even featured Chomsky at some of their concerts. With thousands packed into a concert hall, the slender Chomsky would come out onstage and ruminate on the horrors of American capitalism. Other rock bands have proclaimed him their hero, and one even named itself “Chomsky” in veneration.

Chomsky regularly lectures before thousands of people. In Blue State strongholds like Berkeley, California, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, hundreds are turned away at the door. Even in Texas, the heart of Bush Country, a recent campus appearance brought two thousand to the auditorium. David Barsamian, host of Alternative Radio, explains that the professor “is for many of us our rabbi, our preacher, our rinpoche, our pundit, our imam, our sensei.”(2)

Chomsky plays the part. He dresses simply, proclaims his lack of interest in material things, and holds forth like a modern-day Gandhi. His low-key, deliberate manner is part of his secret. MIT colleague Steven Pinker recalls, “My first impression of him was, like many people, one of awe.”(3)

Despite his voluminous output, Chomsky’s message is remarkably simple: Do you see horror and evil in the world? Capitalism and the American military-industrial complex are to blame. He has charged that the crimes of democratic capitalism are “monstrously worse” than those of communism.(4) Spin magazine has called him “a capitalist's worst nightmare.” He considers the United States a “police state.”

Chomsky often calls himself an “American dissident,” comparing himself to dissidents in the former Soviet Union. He calls his critics “commissars” and says their tactics are familiar to any student of police state behavior. When asked by a reporter why he is ignored by official Washington, he said, “It's been done throughout history. How were dissidents treated in the Soviet Union?”(5) (Hint: They weren’t “ignored”; they were harassed or imprisoned by the KGB.) Yet despite its manifest absurdity, visions of Chomsky as some sort of American Sakharov have caught on. In Great Britain he has been welcomed by Labor MPs and called America's “dissident-in-chief.”

But Chomsky's image and persona, carefully cultivated and encouraged by his followers over the decades, is nothing more than a well-constructed charade. Chomsky has built a highly successful career by abandoning the very ideas and principles he claims to hold dear. Indeed, his greatest accomplishment is not intellectual but entrepreneurial: He has figured out how to make a nice living as a self-described “anarchist-socialist” dissident in a capitalist society. Disdaining the petty contradictions that limit other men's achievements, he has marketed himself as a courageous truth-teller constantly threatened with censorship while publishing dozens of books and holding a tenured position at one of the world’s most prestigious universities. Most audaciously, he has enriched himself by taking millions from the Pentagon while denouncing it as the epitome of evil.

This hypocrisy is particularly stunning because he first entered the national political stage in 1967 with an impassioned article in the New York Review of Books called “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” in which he challenged the nation’s writers and thinkers “to speak the truth and to expose lies.” He attacked establishment figures like Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Henry Kissinger, claiming that they demonstrated a “hypocritical moralism” by professing to be something they were not. Chomsky long ago embraced the leftist notion that the personal is political, and that intellectuals should be held strictly accountable for what they say and do. His advice to young people in a recent interview: “Think for yourselves, and observe elementary moral principles, such as taking responsibility for your actions, or inactions.”(6)

Chomsky has made a career out of scrutinizing and passing judgment on others. But he has always worked to avoid similar scrutiny. As he told a National Public Radio (NPR) interviewer, he was not going to discuss “the house, the children, personal life--anything like that . . . This is not about a person. It's about ideas and principles.” But in a very real way it is all about Chomsky. Is this self-professed American Sakharov really who he claims to be? Does he live by the “moral truisms” with which he has pummeled others over the past four decades?

Let's start with Chomsky's bête noire, the American military.

To hear Chomsky describe it, the Pentagon has got to be one of the most evil institutions in world history. He has called it several times “the most hideous institution on this earth” and declares that it “constitutes a menace to human life.”(7) More to the point, the military has no business being on college campuses, whether recruiting, providing money for research, or helping students pay for college. Professors shouldn't work with the Pentagon, he has said, and instead should fight racism, poverty, and repression.(8) Universities shouldn't take Pentagon research money because it ends up serving the Pentagon's sinister goal of “militarizing” American society.(9) He’s also against college students getting ROTC scholarships, and from Vietnam to the Gulf War he has helped in efforts to drive the program off college campuses.(10)

So imagine my surprise when I discovered Chomsky's lucrative secret: He himself has been paid millions by the Pentagon over the last forty years. Conveniently, he also claims that it is morally acceptable.

Chomsky’s entrance into the world of academe came in 1955 when he received his PhD. He was already a political radical, having determined at the age of ten that capitalism and the American military-industrial complex were dangerous and repugnant. You might think that Chomsky, being a linguist, worked for the MIT Linguistics Department when he joined the faculty. But in fact, Chomsky chose to work for the Research Laboratory of Electronics, which was funded entirely by the Pentagon and a few multinational corporations. Because of the largesse from this “menace to human life,” lab employees like Chomsky enjoyed a light teaching load, an extensive staff, and a salary that was roughly 30 percent higher than equivalent positions at other universities.

Over the next half century, Chomsky would make millions by cashing checks from “the most hideous institution on this earth.”

He wrote his first book, Syntactic Structures, with grants from the U.S. Army (Signal Corps), the air force (Office of Scientific Research, Air Research, and Development Command), and the Office of Naval Research. Though Chomsky says that American corporations “are just as totalitarian as Bolshevism and fascism,” he apparently didn't mind taking money from them, either, because the Eastman Kodak Corporation also provided financial support.

His next book, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, was produced with money from the Joint Services Electronic Program (U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, and U.S. Air Force) as well as the U.S. Air Force Electronic Systems Division.

Serving this “fascist institution” (as he has repeatedly called it) became a family affair when his wife, Carol, also an accomplished linguist, signed on for Pentagon work participating in a DoD-funded project called “Baseball.”(11)

Why would the Pentagon fund research into linguistics? Were they simply interested in advancing science? Chomsky would call anyone who believed such a thing supremely naive. As Chomsky well knew, his work in linguistics was considered vital by the air force and others to improve their “increasingly large investment in so-called ‘command and control’ computer systems” that were being used “to support our forces in Vietnam.” As air force colonel Edmund P. Gaines put it in 1971, “Since the computer cannot ‘understand’ English, the commanders’ queries must be translated into a language that the computer can deal with; such languages resemble English very little, either in their form or in the ease with which they are learned and used.”(12)

Given Chomsky's high profile and shrill rhetoric, it is amazing that he has never been called on this glaring hypocrisy. The one example I could find when it actually became an issue was back in 1967, when Chomsky famously challenged his fellow professors to take moral responsibility for their actions, denounce the Pentagon, and admit that they were compromised by advising the government. George Steiner, a professor at Columbia, wrote Chomsky a letter that was published in the New York Review of Books, asking him earnestly: What action do you urge? And he directly asked: “Will Noam Chomsky announce that he will stop teaching at MIT or anywhere in this country so long as torture and napalm go on?” Chomsky had urged people to avoid paying taxes, resist the draft, and protest the war. He even advocated civil violence as a possible solution. But Chomsky balked at Steiner's suggestion. He could have publicly resigned, denounced the Pentagon, and taken a faculty position at any leading university in the country. But Chomsky wasn’t willing to give up his position. Since then, he has tried to avoid discussing the subject. Along the way, he has been paid a nice salary for more than four decades courtesy of the Pentagon.

Armed with evidence of Chomsky’s willingness to accept millions in salary and benefits from the Pentagon while trying to run ROTC off campus, I wrote him an e-mail asking him to explain himself. To his credit, Chomsky did respond. But what he sent back was less than convincing.

“I think we should be responsible for what we do, not for the bureaucratic question of who stamps the paycheck,” he wrote, adding provocatively, “Do you think you are not working for the Pentagon? Ask yourself about the origins of the computer and the Internet you are now using.”

Somehow, the fact that I use the Internet, which was created by the U.S. military, not only means that I am “working for the Pentagon,” it is the moral equivalent of Chomsky himself growing wealthy on Pentagon contracts. I don't know about you, but I'm still waiting for my check.

Intriguingly, Chomsky seems to have taken me for someone even farther to the left than he is. Thus as our correspondence continued, he suddenly grew defensive and accused me of attacking “those who have not been living up to your exalted standards.”

But of course it was Chomsky himself who had created this “exalted” standard by condemning those who might consider taking grants or scholarships from the Pentagon.

When Chomsky appears on college campuses, he usually dresses in a rumpled shirt and jacket. He is identified with dozens of left-wing causes and professes to speak for the poor, the oppressed, and the “victims of capitalism.” But Chomsky is himself a shrewd capitalist, worth millions, with money in the dreaded and evil stock market, and at least one tax haven to cut down on those pesky inheritance taxes that he says are so important.

Chomsky describes himself as a “socialist” whose goal is a “post-capitalist society worth living in or fighting for.”(13) He has called capitalism a “grotesque catastrophe” and a doctrine “crafted to induce hopelessness, resignation, and despair.” When speaking about class struggle, Chomsky uses terms like “us” versus “them.” Them includes “the top ten percent of taxpayers” (the bracket he himself occupies). Us, he says with truly audacious dishonesty, includes the other 90 percent. He further polishes his radical credentials by boasting about how he loves to spend time with“unemployed working class, activists of one kind or another, those considered to be riff-raff.”(14)

Yet this man of the people, who is among the top 2 percent in the United States in net wealth, moved his family out of Cambridge, Massachusetts—hardly a working-class district to begin with—to the even more affluent wooded suburb of Lexington, where he was even less likely to mingle with blue–collar types. Moreover, he made the move around the time forced busing was being imposed on the Boston area; Lexington was exempt from the court order. Today, America's leading socialist owns a home worth over $850,000 and a vacation home in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, valued in excess of $1.2 million. Chomsky's home on the Cape is smack in the middle of a state park, which prevents any condos from going up nearby and obstructing his view. And don't look for oppressed minorities in either neighborhood. This self–described admirer of the Black Panthers, who says intellectuals must combat “all forms of racism” and complains that America “excludes” blacks from large parts of the country, owns a home in a town with a black population of 1.1 percent.(15)

Chomsky is not lonely in Wellfleet. His close friend and fellow radical Howard Zinn, author of A People's History of America, also makes his home there. Zinn has made a comfortable living over the years trumpeting his economic idea “that there should be no disproportions in the world,” that everyone should basically have the same amount of wealth. He is also quick to pull the trigger and use words like perpetual racism and racist segregation in American society.(16) For all of his talk, Zinn owns two homes in expensive lily–white Wellfleet and a third in multicultural Auburndale (minority population 3.3 percent). A bit disproportionate, don't you think?

Social Parasite, Economic

Protectionist, Amoral Defense

Contractor

I never thought a self–described socialist dissident and anti–imperialist crusader could be so thin–skinned.

I had sent Noam Chomsky several e-mails, questioning him in a mild but insistent way about his personal wealth, investments, and legal maneuvers to avoid paying taxes. What I got back was a stream of invective and some of the most creative logic I have ever seen in my life. No wonder he is considered one of the most important linguists in the world; he's adept at twisting words.

Noam Chomsky doesn't look like your typical revolutionary. The soft-spoken MIT professor is thin and poorly dressed, with a shy smile and gentle manner. But when he speaks or writes about America, the Pentagon, and capitalism, this self-appointed “champion of the ordinary guy” erupts as if the wrath of God had descended from heaven.

Chomsky doesn't think America is a free country: “The American electoral system is a series of four-year dictatorships.” There is no real free press, only “brainwashing under freedom.” In his book What Uncle Sam Really Wants, he describes an America on par with Nazi Germany. “Legally speaking,” he says, “there's a very solid case for impeaching every American president since the Second World War. They've all been either outright war criminals or involved in serious war crimes.” His views on capitalism? Put it up there with Nazism. Don't even ask about the Pentagon. It's the most vile institution on the face of the earth.

Chomsky may sound like a crank, but he’s a crank taken seriously around the world. Hundreds of thousands of college students read his books. Michael Moore has claimed him as a mentor of sorts, and the leadership of the AFL-CIO has gone to him for political advice. The Guardian declares that he “ranks with Marx, Shakespeare, and the Bible as one of the most quoted sources in the humanities.” Robert Barsky, in a glowing biography, claims that Chomsky “will be for future generations what Galileo, Descartes, Newton, Mozart or Picasso have been for ours.”(1)

Though he originally made his name as a professor of linguistics, his political radicalism has made him a superstar. He is embraced by entertainers and actors as some kind of modern-day Buddha. Bono, of the band U2, calls him “the Elvis of Academia.” On Saturday Night Live, a cast member carried a copy of his collected works during one skit in obvious homage to him. In the film Good Will Hunting, Matt Damon played a brilliant young man who quotes Chomsky like some Old Testament prophet. The rock band Pearl Jam even featured Chomsky at some of their concerts. With thousands packed into a concert hall, the slender Chomsky would come out onstage and ruminate on the horrors of American capitalism. Other rock bands have proclaimed him their hero, and one even named itself “Chomsky” in veneration.

Chomsky regularly lectures before thousands of people. In Blue State strongholds like Berkeley, California, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, hundreds are turned away at the door. Even in Texas, the heart of Bush Country, a recent campus appearance brought two thousand to the auditorium. David Barsamian, host of Alternative Radio, explains that the professor “is for many of us our rabbi, our preacher, our rinpoche, our pundit, our imam, our sensei.”(2)

Chomsky plays the part. He dresses simply, proclaims his lack of interest in material things, and holds forth like a modern-day Gandhi. His low-key, deliberate manner is part of his secret. MIT colleague Steven Pinker recalls, “My first impression of him was, like many people, one of awe.”(3)

Despite his voluminous output, Chomsky’s message is remarkably simple: Do you see horror and evil in the world? Capitalism and the American military-industrial complex are to blame. He has charged that the crimes of democratic capitalism are “monstrously worse” than those of communism.(4) Spin magazine has called him “a capitalist's worst nightmare.” He considers the United States a “police state.”

Chomsky often calls himself an “American dissident,” comparing himself to dissidents in the former Soviet Union. He calls his critics “commissars” and says their tactics are familiar to any student of police state behavior. When asked by a reporter why he is ignored by official Washington, he said, “It's been done throughout history. How were dissidents treated in the Soviet Union?”(5) (Hint: They weren’t “ignored”; they were harassed or imprisoned by the KGB.) Yet despite its manifest absurdity, visions of Chomsky as some sort of American Sakharov have caught on. In Great Britain he has been welcomed by Labor MPs and called America's “dissident-in-chief.”

But Chomsky's image and persona, carefully cultivated and encouraged by his followers over the decades, is nothing more than a well-constructed charade. Chomsky has built a highly successful career by abandoning the very ideas and principles he claims to hold dear. Indeed, his greatest accomplishment is not intellectual but entrepreneurial: He has figured out how to make a nice living as a self-described “anarchist-socialist” dissident in a capitalist society. Disdaining the petty contradictions that limit other men's achievements, he has marketed himself as a courageous truth-teller constantly threatened with censorship while publishing dozens of books and holding a tenured position at one of the world’s most prestigious universities. Most audaciously, he has enriched himself by taking millions from the Pentagon while denouncing it as the epitome of evil.

This hypocrisy is particularly stunning because he first entered the national political stage in 1967 with an impassioned article in the New York Review of Books called “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” in which he challenged the nation’s writers and thinkers “to speak the truth and to expose lies.” He attacked establishment figures like Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Henry Kissinger, claiming that they demonstrated a “hypocritical moralism” by professing to be something they were not. Chomsky long ago embraced the leftist notion that the personal is political, and that intellectuals should be held strictly accountable for what they say and do. His advice to young people in a recent interview: “Think for yourselves, and observe elementary moral principles, such as taking responsibility for your actions, or inactions.”(6)

Chomsky has made a career out of scrutinizing and passing judgment on others. But he has always worked to avoid similar scrutiny. As he told a National Public Radio (NPR) interviewer, he was not going to discuss “the house, the children, personal life--anything like that . . . This is not about a person. It's about ideas and principles.” But in a very real way it is all about Chomsky. Is this self-professed American Sakharov really who he claims to be? Does he live by the “moral truisms” with which he has pummeled others over the past four decades?

Let's start with Chomsky's bête noire, the American military.

To hear Chomsky describe it, the Pentagon has got to be one of the most evil institutions in world history. He has called it several times “the most hideous institution on this earth” and declares that it “constitutes a menace to human life.”(7) More to the point, the military has no business being on college campuses, whether recruiting, providing money for research, or helping students pay for college. Professors shouldn't work with the Pentagon, he has said, and instead should fight racism, poverty, and repression.(8) Universities shouldn't take Pentagon research money because it ends up serving the Pentagon's sinister goal of “militarizing” American society.(9) He’s also against college students getting ROTC scholarships, and from Vietnam to the Gulf War he has helped in efforts to drive the program off college campuses.(10)

So imagine my surprise when I discovered Chomsky's lucrative secret: He himself has been paid millions by the Pentagon over the last forty years. Conveniently, he also claims that it is morally acceptable.

Chomsky’s entrance into the world of academe came in 1955 when he received his PhD. He was already a political radical, having determined at the age of ten that capitalism and the American military-industrial complex were dangerous and repugnant. You might think that Chomsky, being a linguist, worked for the MIT Linguistics Department when he joined the faculty. But in fact, Chomsky chose to work for the Research Laboratory of Electronics, which was funded entirely by the Pentagon and a few multinational corporations. Because of the largesse from this “menace to human life,” lab employees like Chomsky enjoyed a light teaching load, an extensive staff, and a salary that was roughly 30 percent higher than equivalent positions at other universities.

Over the next half century, Chomsky would make millions by cashing checks from “the most hideous institution on this earth.”

He wrote his first book, Syntactic Structures, with grants from the U.S. Army (Signal Corps), the air force (Office of Scientific Research, Air Research, and Development Command), and the Office of Naval Research. Though Chomsky says that American corporations “are just as totalitarian as Bolshevism and fascism,” he apparently didn't mind taking money from them, either, because the Eastman Kodak Corporation also provided financial support.

His next book, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, was produced with money from the Joint Services Electronic Program (U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, and U.S. Air Force) as well as the U.S. Air Force Electronic Systems Division.

Serving this “fascist institution” (as he has repeatedly called it) became a family affair when his wife, Carol, also an accomplished linguist, signed on for Pentagon work participating in a DoD-funded project called “Baseball.”(11)

Why would the Pentagon fund research into linguistics? Were they simply interested in advancing science? Chomsky would call anyone who believed such a thing supremely naive. As Chomsky well knew, his work in linguistics was considered vital by the air force and others to improve their “increasingly large investment in so-called ‘command and control’ computer systems” that were being used “to support our forces in Vietnam.” As air force colonel Edmund P. Gaines put it in 1971, “Since the computer cannot ‘understand’ English, the commanders’ queries must be translated into a language that the computer can deal with; such languages resemble English very little, either in their form or in the ease with which they are learned and used.”(12)

Given Chomsky's high profile and shrill rhetoric, it is amazing that he has never been called on this glaring hypocrisy. The one example I could find when it actually became an issue was back in 1967, when Chomsky famously challenged his fellow professors to take moral responsibility for their actions, denounce the Pentagon, and admit that they were compromised by advising the government. George Steiner, a professor at Columbia, wrote Chomsky a letter that was published in the New York Review of Books, asking him earnestly: What action do you urge? And he directly asked: “Will Noam Chomsky announce that he will stop teaching at MIT or anywhere in this country so long as torture and napalm go on?” Chomsky had urged people to avoid paying taxes, resist the draft, and protest the war. He even advocated civil violence as a possible solution. But Chomsky balked at Steiner's suggestion. He could have publicly resigned, denounced the Pentagon, and taken a faculty position at any leading university in the country. But Chomsky wasn’t willing to give up his position. Since then, he has tried to avoid discussing the subject. Along the way, he has been paid a nice salary for more than four decades courtesy of the Pentagon.

Armed with evidence of Chomsky’s willingness to accept millions in salary and benefits from the Pentagon while trying to run ROTC off campus, I wrote him an e-mail asking him to explain himself. To his credit, Chomsky did respond. But what he sent back was less than convincing.

“I think we should be responsible for what we do, not for the bureaucratic question of who stamps the paycheck,” he wrote, adding provocatively, “Do you think you are not working for the Pentagon? Ask yourself about the origins of the computer and the Internet you are now using.”

Somehow, the fact that I use the Internet, which was created by the U.S. military, not only means that I am “working for the Pentagon,” it is the moral equivalent of Chomsky himself growing wealthy on Pentagon contracts. I don't know about you, but I'm still waiting for my check.

Intriguingly, Chomsky seems to have taken me for someone even farther to the left than he is. Thus as our correspondence continued, he suddenly grew defensive and accused me of attacking “those who have not been living up to your exalted standards.”

But of course it was Chomsky himself who had created this “exalted” standard by condemning those who might consider taking grants or scholarships from the Pentagon.

When Chomsky appears on college campuses, he usually dresses in a rumpled shirt and jacket. He is identified with dozens of left-wing causes and professes to speak for the poor, the oppressed, and the “victims of capitalism.” But Chomsky is himself a shrewd capitalist, worth millions, with money in the dreaded and evil stock market, and at least one tax haven to cut down on those pesky inheritance taxes that he says are so important.

Chomsky describes himself as a “socialist” whose goal is a “post-capitalist society worth living in or fighting for.”(13) He has called capitalism a “grotesque catastrophe” and a doctrine “crafted to induce hopelessness, resignation, and despair.” When speaking about class struggle, Chomsky uses terms like “us” versus “them.” Them includes “the top ten percent of taxpayers” (the bracket he himself occupies). Us, he says with truly audacious dishonesty, includes the other 90 percent. He further polishes his radical credentials by boasting about how he loves to spend time with“unemployed working class, activists of one kind or another, those considered to be riff-raff.”(14)

Yet this man of the people, who is among the top 2 percent in the United States in net wealth, moved his family out of Cambridge, Massachusetts—hardly a working-class district to begin with—to the even more affluent wooded suburb of Lexington, where he was even less likely to mingle with blue–collar types. Moreover, he made the move around the time forced busing was being imposed on the Boston area; Lexington was exempt from the court order. Today, America's leading socialist owns a home worth over $850,000 and a vacation home in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, valued in excess of $1.2 million. Chomsky's home on the Cape is smack in the middle of a state park, which prevents any condos from going up nearby and obstructing his view. And don't look for oppressed minorities in either neighborhood. This self–described admirer of the Black Panthers, who says intellectuals must combat “all forms of racism” and complains that America “excludes” blacks from large parts of the country, owns a home in a town with a black population of 1.1 percent.(15)

Chomsky is not lonely in Wellfleet. His close friend and fellow radical Howard Zinn, author of A People's History of America, also makes his home there. Zinn has made a comfortable living over the years trumpeting his economic idea “that there should be no disproportions in the world,” that everyone should basically have the same amount of wealth. He is also quick to pull the trigger and use words like perpetual racism and racist segregation in American society.(16) For all of his talk, Zinn owns two homes in expensive lily–white Wellfleet and a third in multicultural Auburndale (minority population 3.3 percent). A bit disproportionate, don't you think?

Descriere

In this new book, Schweizer makes it clear that when it comes to what matters most in their lives--the protection of their property, privacy, and families--even the most outspoken liberals jettison their progressive ideas and adopt conservative principles.