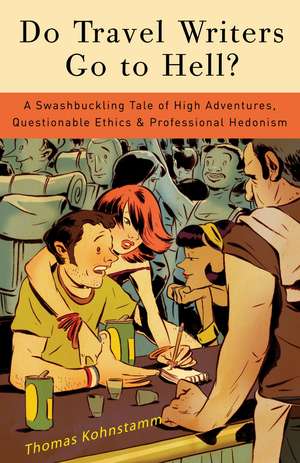

Do Travel Writers Go to Hell?: A Swashbuckling Tale of High Adventures, Questionable Ethics, & Professional Hedonism

Autor Thomas Kohnstammen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2008

WANTED: Travel Writer for Brazil

QUALIFICATIONS REQUIRED

Decisiveness: the ability to desert your entire previous lifeߝincluding well-salaried office job, attractive girlfriend, and basic sanity for less than minimum wage

Attention to detail: the skill to research northeastern Brazil, including transportation, restaurants, hotels, culture, customs, and language, while juggling sleep deprivation, nonstop nightlife, and excessive alcohol consumption

Creativity: the imagination to write about places you never actually visit

Resourcefulness: utilizing persuasion, seduction, and threats, when necessary, to secure a place to stay for the evening once your pitiable advance has been (mis)spent

Resilience: determination to overcome setbacks such as bankruptcy, disillusionment, and an ill-fated one-night stand with an Austrian flight attendant

As Kohnstamm comes to personal terms with each of these job requirements, he unveils the underside of the travel industry and its often-harrowing effect on writers, travelers, and the destinations themselves. Moreover, he invites us into his world of compromising and scandalous situations in one of the most exciting countries as he races against an impossible deadline.

Preț: 110.88 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 166

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.22€ • 21.92$ • 17.66£

21.22€ • 21.92$ • 17.66£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307394651

ISBN-10: 0307394654

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307394654

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

THOMAS KOHNSTAMM was born in 1975 and graduated from Stanford University with an M.A. in Latin American studies. He lives in Seattle.

Extras

1

One in the Hand, Two in the Bush

Roebling.

Roe-bleeeng.

Rrrrroe-bling.

Alone in the fifty-seventh-floor conference room, I repeat the mantra under my breath. I sit in a rigid half-lotus position atop the glass table and watch the suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge flicker against the night sky. The office air is sharp with disinfectant. I take a slug of rum and return to my mantra.

John Roebling had a calling. Unfortunately for him, after the buildup, design, preparation, and politicking for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, the hapless bastard promptly dropped dead. His son, Washington, brought the bridge to completion, but not without picking up a case of the bends and almost dying in the process. Neither man ever wavered from a life of dedication, direction, and diligence.

A lot of good it did either of them.

I remove my battered leather shoes, the toes stained gray with salt from the slushy city sidewalks, and knead my left foot through my sweaty dress sock. Hundreds of pairs of headlights move in a stream back and forth across the bridge.

Yesterday during a meeting in this same conference room, a neckless, pockmarked banker pointed out that the name the bends was, in fact, coined during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Hundreds of laborers toiled on the footing of the bridge, eighty feet below the surface of the river. They worked in nine-foot-high wooden boxes known as caissons, which were pumped full of compressed air and lowered to the depths with the men inside. After resurfacing, scores of workers were inflicted with a mysterious illness. Crippling joint pain. Mental deterioration. Paralysis. And for a few, agonizing death. The name the bends was taken from the debilitated posture of the sufferers.

It wasn't until eight years after the bridge construction had started that a French physiologist determined the cause of the illness. Contrary to popular assumption, oxygen is a lesser ingredient in the air that we breathe. Seventy-eight percent of air is comprised of nitrogen, which, under normal circumstances, has no effect on the human body. When breathing air at depth, the water pressure converts the nitrogen in the bloodstream from a gas to a liquid, washing it through the veins and arteries. So long as you resurface at a slow pace, the liquid gradually transforms back into a gas and is disposed of by your body.

If the change of pressure is too sudden, the liquid bursts out of solution, fizzing back into gas. Similar to the millions of microscopic nitrogen bubbles that are released when you crack a can of Guinness, the bubbles surge through the bloodstream. If they don't lodge themselves in your joints, the bubbles charge on the fatal path to your brain. You come up too quickly, you die.

I remove a folded piece of printer paper from my pocket and smooth it open:

Thomas,

I want to know if you'd like do some writing for our new Brazil guidebook?

If you're interested in jumping ship within the next few weeks for Brazil, let me know right away and I could put together an offer for you.

Commissioning Editor--South America & Antarctica

Lonely Planet

Once--maybe when I was first out of school--this opportunity would have been a dream job. It is still seductive, but more along the lines of a cheap one-night-stand. My life is fulfilling in other ways now. I have a steady job, a decent income, a beautiful girlfriend, and an apartment in Manhattan. I finally have everything that I am supposed to have. Besides, between 9/11, SARS, Iraq, Bali, and Madrid, it can't possibly be a good time to dive headfirst into travel writing. But I won't I lie: I have always been a sucker for a cheap one-night-stand.

God knows, I can already feel myself coming up too fast.

For most people, November 24 is not a special day. Sure, it hosts Thanksgiving every few years, but I could care less about that. In Seattle, where few things out-of-the-ordinary ever happen and where people strive, often pathologically, to maintain a facade of tranquility, the day has a different significance.

On November 24, 1971, a balding, middle-aged man boarded a flight from Portland to Seattle. He used the name Dan Cooper. He dressed in a black suit, a black overcoat, black sunglasses, and a narrow black tie with a pearl stick pin. Cooper hijacked the Boeing 727 with a briefcase full of wires and bright red cylinders. The hostages were exchanged for four parachutes and two hundred thousand dollars at Sea-Tac Airport (to put that in perspective, the average cost of a new home in the U.S. in 1971 was $28,000).

DB Cooper, as the press mistakenly dubbed him, demanded to be flown to Mexico. He parachuted out of the plane somewhere over southern Washington State and disappeared. Maybe DB died in the jump. Maybe he got away with the money. Nobody knows. But legend has it that DB was a man so disenchanted with his life that he gambled it all on a way out. The point isn't whether he made it or not. The point is that this little bald man didn't spend one more day pumping gas in Tallahassee or adjusting claims in Denver. He didn't waste one more day wondering, "What if?"

I nominate Cooper as the patron saint of disillusioned men, particularly those who, like me, were born in Seattle on November 24.

The phone rings in the conference room. It is the blipping staccato ring of all office phones. I am jolted back to the reality that I have hours of work ahead of me. The digital clock on the phone reads 9:42 p.m.

Tucking the pint bottle of rum into the waist of my pants, I answer with a cautious "Hello."

"Thomas? WHAT ARE YOU DOING IN THE CONFERENCE ROOM, DAMMIT. I knew I could find you there. You and I need to have a talk," my boss snarls. "I am coming by your cube in fifteen minutes. You'd better be there, with the WorldCom spreadsheet ready for me to look at."

I tiptoe back into my cubicle, successfully avoiding anyone in the hallways. I hold my head in my hands, shirt sleeves rolled up, with cold sweat dripping down my sides. My tacky palms are crisscrossed with hairs from my suddenly receding hairline. After the final sip of a metallic-sweet Red Bull, I chew a handful of gum and look across the tops of the cubicles, scanning for other workers. The office appears empty, except for the faint tapping of keyboards somewhere down the hall.

Welcome to life on Wall Street. With such a character-defining foothold in the career world, I no longer have to make excuses for the life I lead. No longer do I have to explain my directionless postcollegiate life to incredulous eyes and repetitive questions, like: "What are you doing next year?" "Don't you want to do something with your life?" and my favorite, "When are you going to get a real job?" I am no longer just Thomas, the supposed slacker, backpacker bum, or permanent student. I am Thomas, the employee of , , & LLP, and I am going places.

I make more money than I reasonably should, putting papers into chronological order (chroning, in office-speak). My skill set also includes entering numbers into Excel spreadsheets and working the copier and fax machine. Between those projects, I search for old high school friends' names on Google; play online Jeopardy against my office trivia nemesis, Jerry; and generally while away the hours of my life. Jerry thinks that he is better at Jeopardy than me, but really he's just faster with the mouse.

Yes, I know, I really have it pretty good. There are people starving in Africa. And there are plenty of people here in New York who would love the chance to be in a cubicle all day and not have to operate deep-fat fryers, drive garbage trucks, suck dicks, or whatever it is they do. The problem is that I am an ungrateful by-product of a prosperous society--the offal of opportunity. I am just another liberal arts graduate who bought the idea that life and career would be a fulfilling intellectual journey. Unfortunately, I am performing a glorified version of punching the time clock, and the financial rewards don't come anywhere near filling the emotional void of such diminished expectations.

But let's face it: rebellion is passe. My parents' generation already proved that--over time--rebellion boils down to little more than Saab ownership and an annual contribution to public radio. The old icons have been co-opted. JoseŽ Mart’ is a brand of mojito mix. Che Guevara is a T-shirt. Cherokees are SUVs, and Apaches are helicopter gunships.

The American Dream is for immigrants. The rest of us are better acquainted with entitlement or boredom than we are with our own survival mechanisms. And when confronted with a fight-or-flight scenario, the latter usually takes precedence. Escape is our action of choice: escape through pharmaceuticals, escape through technology, and plain old running away in search of something else, anything else. I rummage through the back of my desk drawer looking for a loose Vicodin or a Klonopin. The best thing I come up with is Wite-Out, but I'm not that desperate. Yet.

I continually revisit the words of some sociologist who I read in college. I think that it was Weber or Durkheim. Either is usually a fair guess. He believed that the modern mind is determined to expand its repertoire of experiences, and is bent on avoiding any specialization that threatens to interrupt the search for alternatives and novelty. Many people would call that approach to life a crisis, immaturity, or being out of touch with reality. It could also be called the New American Dream. Fuck the simple pursuit of financial stability. Here's to finding fulfillment in novelty, excitement, adventure, and autonomy.

Following the cue of one of our office team-building exercises, I come up with the following life goals and painstakingly write them out on Day-Glo yellow Post-it notes:

Ski the Andes Wake up naked

and from a rum

surf Sumatra. blackout

in rural Cuba.

Ride the roof Win or lose

of a bus through a bar fight

the Himalayan in a dusty

Foothills. border town.

Kick my mind Sleep with at

into the stratosphere least one woman

with ayahuasca (preferably more)

in the Amazon. from each continent.

One by one, I stick the notes around the edge of my computer monitor. All evenly spaced. They're not the clear career objectives of a John Roebling, but for me, they'll have to do.

My desk phone rings.

"Yes?"

"She found you, huh? I heard you sneaking back to your desk," says Anna. Though she is only two years out of Dartmouth, Anna has a mature professional edge. She is invariably the last person to leave the office at night and goes about her tasks with pleasure, frequently asking for more work. Her try-hard humor and enthusiastic friendliness have inspired suspicion in our more acerbic and cynical co-workers. Anna and I couldn't be more different as employees, but have the camaraderie of workplace outcasts.

"Yuck. I'm happy that it's you and not me who's working for Marilyn. I can't stand that cuckoo," Anna offers.

"Marilyn's just having another personal crisis. Unfortunately, as her assistant, I'm a reservoir tip for her self-loathing." I would like to give Marilyn the benefit of the doubt. She once worked for the National Organization for Women, but soon tired of surviving on a pittance and now occupies her waking hours as legal defense for well-known misogynists and womanizers--misogynists and womanizers with their hands in very lucrative business.

"At least you're not working with Allen," she says.

I tell her I wish that were true. If he hadn't dumped a bunch of work on me, I'd be done and home by now. Allen is like the evil asshole twin of Skippy from Family Ties, brandishing his papier-mache bravado, trying to assert his superiority over me in every interaction. Although he's an attorney (and one of my bosses), we are about the same age. If we had been in high school together, I would have beat his ass. The problem is, he knows that and takes pleasure in harassing me. This afternoon, he mocked me for not knowing a keyboard shortcut in Word and then dropped a stack of file folders right onto my lap. I am sure that he ran back to his office, reminisced for a moment, and treated himself to some rough masturbation.

Sometimes after work I go to my overpriced gym on Lafayette Street and kick and punch the heavy bag, pretending that it's Allen. It's not only a great workout, but a dependable way to unwind.

"Allen and Marilyn," Anna says. "Dang. Listen, Thomas, I can stay and give you a hand."

Sometimes, I get the feeling Anna sees me as an endangered species, a manatee who will swim headfirst into a propeller if not protected by outside intervention. Sometimes, I can't believe people like her actually exist on Wall Street. But she doesn't understand that, for me, the pin is already out of the grenade. She has better things to do with her time. She has a career to think about. I kindly decline her offer.

I never planned to end up here. After college, I traveled, stumbled my way through graduate school, and tried to discover what my life was about. While I was busy figuring out nothing, or at least nothing that advanced my career or future, my friends moved to the Bay Area, got entry-level jobs with no real work responsibilities for $75K per year, acquired hundreds of thousands' worth of stock options, and attended ridiculous site launch parties on the tab of venture capitalists. If you weren't involved with a pre-Initial Public Offering startup or the financing behind a pre-IPO startup, you were wasting the greatest economic opportunity since buying stock on margin or selling junk bonds.

It was the dawn of a new era. Technology was guaranteed to unchain us from traditional work roles, from the stuffy expectations heaped upon us by past generations. We would be able to create the careers and lifestyles of our choosing. Business was organized around foosball tables and paintball outings. Deep house music went practically mainstream in SF, LA, and NYC. Ecstasy and hydroponics powered the irrational exuberance and infectious hedonism. Imagination was the only limiting factor. The good times were poised to endure so long as the optimism and energy of our generation endured--faith in the potential and inherent goodness of technology would fill in the gaps. We were to change the course of history. It was the '60s love generation redux, but with vague political goals, lucrative day jobs, and expensive sneakers.

I bided my time on the periphery of this wanton excess, while I did an esoteric advanced degree in Latin American Studies, followed by the world's shortest PhD in the department of Social Policy, whatever that is. I lasted through orientation and two classes in the PhD program before deciding to flee. At that point, being an escape artist was not only low risk, it was encouraged. The other side held the offer of consulting gigs, website positions, and stock options as far as the eye could see.

One in the Hand, Two in the Bush

Roebling.

Roe-bleeeng.

Rrrrroe-bling.

Alone in the fifty-seventh-floor conference room, I repeat the mantra under my breath. I sit in a rigid half-lotus position atop the glass table and watch the suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge flicker against the night sky. The office air is sharp with disinfectant. I take a slug of rum and return to my mantra.

John Roebling had a calling. Unfortunately for him, after the buildup, design, preparation, and politicking for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, the hapless bastard promptly dropped dead. His son, Washington, brought the bridge to completion, but not without picking up a case of the bends and almost dying in the process. Neither man ever wavered from a life of dedication, direction, and diligence.

A lot of good it did either of them.

I remove my battered leather shoes, the toes stained gray with salt from the slushy city sidewalks, and knead my left foot through my sweaty dress sock. Hundreds of pairs of headlights move in a stream back and forth across the bridge.

Yesterday during a meeting in this same conference room, a neckless, pockmarked banker pointed out that the name the bends was, in fact, coined during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. Hundreds of laborers toiled on the footing of the bridge, eighty feet below the surface of the river. They worked in nine-foot-high wooden boxes known as caissons, which were pumped full of compressed air and lowered to the depths with the men inside. After resurfacing, scores of workers were inflicted with a mysterious illness. Crippling joint pain. Mental deterioration. Paralysis. And for a few, agonizing death. The name the bends was taken from the debilitated posture of the sufferers.

It wasn't until eight years after the bridge construction had started that a French physiologist determined the cause of the illness. Contrary to popular assumption, oxygen is a lesser ingredient in the air that we breathe. Seventy-eight percent of air is comprised of nitrogen, which, under normal circumstances, has no effect on the human body. When breathing air at depth, the water pressure converts the nitrogen in the bloodstream from a gas to a liquid, washing it through the veins and arteries. So long as you resurface at a slow pace, the liquid gradually transforms back into a gas and is disposed of by your body.

If the change of pressure is too sudden, the liquid bursts out of solution, fizzing back into gas. Similar to the millions of microscopic nitrogen bubbles that are released when you crack a can of Guinness, the bubbles surge through the bloodstream. If they don't lodge themselves in your joints, the bubbles charge on the fatal path to your brain. You come up too quickly, you die.

I remove a folded piece of printer paper from my pocket and smooth it open:

Thomas,

I want to know if you'd like do some writing for our new Brazil guidebook?

If you're interested in jumping ship within the next few weeks for Brazil, let me know right away and I could put together an offer for you.

Commissioning Editor--South America & Antarctica

Lonely Planet

Once--maybe when I was first out of school--this opportunity would have been a dream job. It is still seductive, but more along the lines of a cheap one-night-stand. My life is fulfilling in other ways now. I have a steady job, a decent income, a beautiful girlfriend, and an apartment in Manhattan. I finally have everything that I am supposed to have. Besides, between 9/11, SARS, Iraq, Bali, and Madrid, it can't possibly be a good time to dive headfirst into travel writing. But I won't I lie: I have always been a sucker for a cheap one-night-stand.

God knows, I can already feel myself coming up too fast.

For most people, November 24 is not a special day. Sure, it hosts Thanksgiving every few years, but I could care less about that. In Seattle, where few things out-of-the-ordinary ever happen and where people strive, often pathologically, to maintain a facade of tranquility, the day has a different significance.

On November 24, 1971, a balding, middle-aged man boarded a flight from Portland to Seattle. He used the name Dan Cooper. He dressed in a black suit, a black overcoat, black sunglasses, and a narrow black tie with a pearl stick pin. Cooper hijacked the Boeing 727 with a briefcase full of wires and bright red cylinders. The hostages were exchanged for four parachutes and two hundred thousand dollars at Sea-Tac Airport (to put that in perspective, the average cost of a new home in the U.S. in 1971 was $28,000).

DB Cooper, as the press mistakenly dubbed him, demanded to be flown to Mexico. He parachuted out of the plane somewhere over southern Washington State and disappeared. Maybe DB died in the jump. Maybe he got away with the money. Nobody knows. But legend has it that DB was a man so disenchanted with his life that he gambled it all on a way out. The point isn't whether he made it or not. The point is that this little bald man didn't spend one more day pumping gas in Tallahassee or adjusting claims in Denver. He didn't waste one more day wondering, "What if?"

I nominate Cooper as the patron saint of disillusioned men, particularly those who, like me, were born in Seattle on November 24.

The phone rings in the conference room. It is the blipping staccato ring of all office phones. I am jolted back to the reality that I have hours of work ahead of me. The digital clock on the phone reads 9:42 p.m.

Tucking the pint bottle of rum into the waist of my pants, I answer with a cautious "Hello."

"Thomas? WHAT ARE YOU DOING IN THE CONFERENCE ROOM, DAMMIT. I knew I could find you there. You and I need to have a talk," my boss snarls. "I am coming by your cube in fifteen minutes. You'd better be there, with the WorldCom spreadsheet ready for me to look at."

I tiptoe back into my cubicle, successfully avoiding anyone in the hallways. I hold my head in my hands, shirt sleeves rolled up, with cold sweat dripping down my sides. My tacky palms are crisscrossed with hairs from my suddenly receding hairline. After the final sip of a metallic-sweet Red Bull, I chew a handful of gum and look across the tops of the cubicles, scanning for other workers. The office appears empty, except for the faint tapping of keyboards somewhere down the hall.

Welcome to life on Wall Street. With such a character-defining foothold in the career world, I no longer have to make excuses for the life I lead. No longer do I have to explain my directionless postcollegiate life to incredulous eyes and repetitive questions, like: "What are you doing next year?" "Don't you want to do something with your life?" and my favorite, "When are you going to get a real job?" I am no longer just Thomas, the supposed slacker, backpacker bum, or permanent student. I am Thomas, the employee of , , & LLP, and I am going places.

I make more money than I reasonably should, putting papers into chronological order (chroning, in office-speak). My skill set also includes entering numbers into Excel spreadsheets and working the copier and fax machine. Between those projects, I search for old high school friends' names on Google; play online Jeopardy against my office trivia nemesis, Jerry; and generally while away the hours of my life. Jerry thinks that he is better at Jeopardy than me, but really he's just faster with the mouse.

Yes, I know, I really have it pretty good. There are people starving in Africa. And there are plenty of people here in New York who would love the chance to be in a cubicle all day and not have to operate deep-fat fryers, drive garbage trucks, suck dicks, or whatever it is they do. The problem is that I am an ungrateful by-product of a prosperous society--the offal of opportunity. I am just another liberal arts graduate who bought the idea that life and career would be a fulfilling intellectual journey. Unfortunately, I am performing a glorified version of punching the time clock, and the financial rewards don't come anywhere near filling the emotional void of such diminished expectations.

But let's face it: rebellion is passe. My parents' generation already proved that--over time--rebellion boils down to little more than Saab ownership and an annual contribution to public radio. The old icons have been co-opted. JoseŽ Mart’ is a brand of mojito mix. Che Guevara is a T-shirt. Cherokees are SUVs, and Apaches are helicopter gunships.

The American Dream is for immigrants. The rest of us are better acquainted with entitlement or boredom than we are with our own survival mechanisms. And when confronted with a fight-or-flight scenario, the latter usually takes precedence. Escape is our action of choice: escape through pharmaceuticals, escape through technology, and plain old running away in search of something else, anything else. I rummage through the back of my desk drawer looking for a loose Vicodin or a Klonopin. The best thing I come up with is Wite-Out, but I'm not that desperate. Yet.

I continually revisit the words of some sociologist who I read in college. I think that it was Weber or Durkheim. Either is usually a fair guess. He believed that the modern mind is determined to expand its repertoire of experiences, and is bent on avoiding any specialization that threatens to interrupt the search for alternatives and novelty. Many people would call that approach to life a crisis, immaturity, or being out of touch with reality. It could also be called the New American Dream. Fuck the simple pursuit of financial stability. Here's to finding fulfillment in novelty, excitement, adventure, and autonomy.

Following the cue of one of our office team-building exercises, I come up with the following life goals and painstakingly write them out on Day-Glo yellow Post-it notes:

Ski the Andes Wake up naked

and from a rum

surf Sumatra. blackout

in rural Cuba.

Ride the roof Win or lose

of a bus through a bar fight

the Himalayan in a dusty

Foothills. border town.

Kick my mind Sleep with at

into the stratosphere least one woman

with ayahuasca (preferably more)

in the Amazon. from each continent.

One by one, I stick the notes around the edge of my computer monitor. All evenly spaced. They're not the clear career objectives of a John Roebling, but for me, they'll have to do.

My desk phone rings.

"Yes?"

"She found you, huh? I heard you sneaking back to your desk," says Anna. Though she is only two years out of Dartmouth, Anna has a mature professional edge. She is invariably the last person to leave the office at night and goes about her tasks with pleasure, frequently asking for more work. Her try-hard humor and enthusiastic friendliness have inspired suspicion in our more acerbic and cynical co-workers. Anna and I couldn't be more different as employees, but have the camaraderie of workplace outcasts.

"Yuck. I'm happy that it's you and not me who's working for Marilyn. I can't stand that cuckoo," Anna offers.

"Marilyn's just having another personal crisis. Unfortunately, as her assistant, I'm a reservoir tip for her self-loathing." I would like to give Marilyn the benefit of the doubt. She once worked for the National Organization for Women, but soon tired of surviving on a pittance and now occupies her waking hours as legal defense for well-known misogynists and womanizers--misogynists and womanizers with their hands in very lucrative business.

"At least you're not working with Allen," she says.

I tell her I wish that were true. If he hadn't dumped a bunch of work on me, I'd be done and home by now. Allen is like the evil asshole twin of Skippy from Family Ties, brandishing his papier-mache bravado, trying to assert his superiority over me in every interaction. Although he's an attorney (and one of my bosses), we are about the same age. If we had been in high school together, I would have beat his ass. The problem is, he knows that and takes pleasure in harassing me. This afternoon, he mocked me for not knowing a keyboard shortcut in Word and then dropped a stack of file folders right onto my lap. I am sure that he ran back to his office, reminisced for a moment, and treated himself to some rough masturbation.

Sometimes after work I go to my overpriced gym on Lafayette Street and kick and punch the heavy bag, pretending that it's Allen. It's not only a great workout, but a dependable way to unwind.

"Allen and Marilyn," Anna says. "Dang. Listen, Thomas, I can stay and give you a hand."

Sometimes, I get the feeling Anna sees me as an endangered species, a manatee who will swim headfirst into a propeller if not protected by outside intervention. Sometimes, I can't believe people like her actually exist on Wall Street. But she doesn't understand that, for me, the pin is already out of the grenade. She has better things to do with her time. She has a career to think about. I kindly decline her offer.

I never planned to end up here. After college, I traveled, stumbled my way through graduate school, and tried to discover what my life was about. While I was busy figuring out nothing, or at least nothing that advanced my career or future, my friends moved to the Bay Area, got entry-level jobs with no real work responsibilities for $75K per year, acquired hundreds of thousands' worth of stock options, and attended ridiculous site launch parties on the tab of venture capitalists. If you weren't involved with a pre-Initial Public Offering startup or the financing behind a pre-IPO startup, you were wasting the greatest economic opportunity since buying stock on margin or selling junk bonds.

It was the dawn of a new era. Technology was guaranteed to unchain us from traditional work roles, from the stuffy expectations heaped upon us by past generations. We would be able to create the careers and lifestyles of our choosing. Business was organized around foosball tables and paintball outings. Deep house music went practically mainstream in SF, LA, and NYC. Ecstasy and hydroponics powered the irrational exuberance and infectious hedonism. Imagination was the only limiting factor. The good times were poised to endure so long as the optimism and energy of our generation endured--faith in the potential and inherent goodness of technology would fill in the gaps. We were to change the course of history. It was the '60s love generation redux, but with vague political goals, lucrative day jobs, and expensive sneakers.

I bided my time on the periphery of this wanton excess, while I did an esoteric advanced degree in Latin American Studies, followed by the world's shortest PhD in the department of Social Policy, whatever that is. I lasted through orientation and two classes in the PhD program before deciding to flee. At that point, being an escape artist was not only low risk, it was encouraged. The other side held the offer of consulting gigs, website positions, and stock options as far as the eye could see.

Recenzii

"A comic rogue who seems to have modeled his life and prose on Hunter S. Thompson’s… I could not get enough of the most depraved travel book of the year."

—The New York Times

"Hilarious"

—The New York Times Book Review

"the shot heard 'round the travel world…"

—The Washington Post

"A guidebook writer reveals the truth about his trade, in detail that will shock and awe."

—Outside

"It’s Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, but with tourism"

—The New York Observer

"Kohnstamm is nobody's model travel journalist, except maybe Hunter Thompson's… [he’s the] sudden enfant terrible of his field… Do Travel Writers Go To Hell? is the best-written, funniest book of travel literature since Phaic Tan."

—The Philadelphia Inquirer

"Sharp writing and self-deprecating wit add spice to a chronicle of the sometimes absurd world of guidebook writing."

—Booklist

"Readers will relish the countless stories of the author's misadventures, but Kohnstamm brings more than just anecdotes: He offers a solid understanding of the mechanics of the travel-writing industry and a unique ability to illuminate that world to readers. Notable for its spirited prose and insightful exploration of the less-romantic side of travel writing. Kohnstamm is one to watch."

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

—The New York Times

"Hilarious"

—The New York Times Book Review

"the shot heard 'round the travel world…"

—The Washington Post

"A guidebook writer reveals the truth about his trade, in detail that will shock and awe."

—Outside

"It’s Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, but with tourism"

—The New York Observer

"Kohnstamm is nobody's model travel journalist, except maybe Hunter Thompson's… [he’s the] sudden enfant terrible of his field… Do Travel Writers Go To Hell? is the best-written, funniest book of travel literature since Phaic Tan."

—The Philadelphia Inquirer

"Sharp writing and self-deprecating wit add spice to a chronicle of the sometimes absurd world of guidebook writing."

—Booklist

"Readers will relish the countless stories of the author's misadventures, but Kohnstamm brings more than just anecdotes: He offers a solid understanding of the mechanics of the travel-writing industry and a unique ability to illuminate that world to readers. Notable for its spirited prose and insightful exploration of the less-romantic side of travel writing. Kohnstamm is one to watch."

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Descriere

With a gonzo writing style and adventurer persona, Kohnstamm takes readers beyond his often questionable guidebook entries to reveal a disillusioned young man struggling--and often failing--to make good on an impossible assignment.