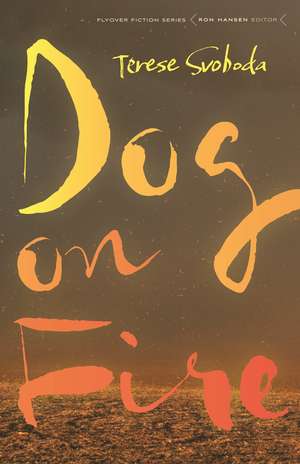

Dog on Fire: Flyover Fiction

Autor Terese Svobodaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 mar 2023

Din seria Flyover Fiction

-

Preț: 157.35 lei

Preț: 157.35 lei -

Preț: 103.29 lei

Preț: 103.29 lei -

Preț: 96.09 lei

Preț: 96.09 lei -

Preț: 105.34 lei

Preț: 105.34 lei -

Preț: 119.58 lei

Preț: 119.58 lei -

Preț: 112.37 lei

Preț: 112.37 lei -

Preț: 73.98 lei

Preț: 73.98 lei -

Preț: 129.50 lei

Preț: 129.50 lei -

Preț: 91.95 lei

Preț: 91.95 lei -

Preț: 105.17 lei

Preț: 105.17 lei -

Preț: 81.64 lei

Preț: 81.64 lei -

Preț: 117.72 lei

Preț: 117.72 lei -

Preț: 90.72 lei

Preț: 90.72 lei -

Preț: 115.67 lei

Preț: 115.67 lei -

Preț: 102.08 lei

Preț: 102.08 lei -

Preț: 107.00 lei

Preț: 107.00 lei -

Preț: 105.36 lei

Preț: 105.36 lei -

Preț: 116.31 lei

Preț: 116.31 lei -

Preț: 109.10 lei

Preț: 109.10 lei -

Preț: 144.34 lei

Preț: 144.34 lei -

Preț: 137.73 lei

Preț: 137.73 lei -

Preț: 106.18 lei

Preț: 106.18 lei -

Preț: 122.67 lei

Preț: 122.67 lei -

Preț: 118.35 lei

Preț: 118.35 lei -

Preț: 116.71 lei

Preț: 116.71 lei -

Preț: 117.53 lei

Preț: 117.53 lei -

Preț: 120.62 lei

Preț: 120.62 lei -

Preț: 95.68 lei

Preț: 95.68 lei -

Preț: 95.45 lei

Preț: 95.45 lei -

Preț: 115.90 lei

Preț: 115.90 lei

Preț: 106.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.40€ • 21.30$ • 16.84£

20.40€ • 21.30$ • 16.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496235169

ISBN-10: 1496235169

Pagini: 204

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Flyover Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496235169

Pagini: 204

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Seria Flyover Fiction

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Terese Svoboda is the award-winning author of twenty-one books of poetry, prose, memoir, biography, and translation, including the novel Bohemian Girl (Nebraska, 2011), the memoir Black Glasses Like Clark Kent, and two forthcoming books of fiction, Roxy and Coco and The Long Swim.

Extras

1

Out of a storm so thick with dust, a storm so charged with first-rate

prelightning ions that the grit flashes and the car dials fade, a storm

so dark no taillight shines through, though drivers have flicked on

every emergency switch, out of a storm even this dust bowl state

stops for, I spot my brother with a shovel.

Men who shovel look alike. They all face where the wood joins

the metal or at least their glance grazes there on its way to the shovel

tip, so all you see is head or hat—in this case, a cap brim, most

likely lettered Feed and Seed if I know my brother, tilted at some

unreadable angle. What I can read while I creep the car forward,

seeing and not seeing, is that he is not about to dig, he has dug; his

shovel is now raised up. What he has dug swirls around us—me,

in my car creeping through all this flying grit, and him, seen just

in the time it takes to see, where lightning now laves and leaves.

Don’t stop, moans the semi behind me, hauling cattle or, empty,

having hauled. Don’t pull over, says the dust smacking the car.

How do I know it’s him I’ve seen? Only my brother would dig

beside the road in this dust, because he is a digger. Besides, the

road’s right next to my father’s land, and along its perimeter my

brother would dig in postholes for the fences that fall over in the

shrinkage of winter or sag with the swell of summer. Or else he

could be digging to cover up something. Or maybe he was digging

just for the hell of it.

I guess that last is what he is doing, with emphasis on hell. Just the

way our cousin in another state was caught outside her parked

vehicle, holding up her unwrapped baby to a tornado—was

caught more than once—my brother has always dug too deep.

The glimpse goes, is gone. But even if I pull over and park here to

check it out—which I should anyway, given that I can’t see a damn

thing and can hear only this semi shortcutting its own way behind

me, honking now and then like a boat lost in fog, the sound a semi

that could wallop right into me would make if it were too close—even

if I do stop and park and get out and walk over to the field

where he must be, he will not be there. He’s dead.

I tap on my brakes. I make the tapping lively, not nervous, as I go

along so slowly—it’s really an sos, not a signal to my brother behind

me. I push my window button again just to hear my windows roll

their clinch even tighter. I don’t want to breathe his dirt in, all that

grit that could be his. We’re already close, too close, eleven months,

one foot in the womb, the other in the—

I tap it out.

If I could Morse code him with these taps, it would be: I’m not

stopping now, the way I never stopped for you before. But there can

be no ifs to think about with the foghorn of the semi rattling my car.

Or is that sound something else? Some other moan? Some way I

bypass him that is deeper, that I can’t get around at all or hear right?

The dust everywhere is so charged that the radio’s gone static. This

charge is my brother’s fault too, a charge he gives off even when he’s

behind me and dead, being someone with too much electricity in his

head that will forever discharge. He had spells. All that electricity

from his petit and grand mal is probably still around here—so

much of it, it probably killed him. If that isn’t enough, he even attracted

electricity, the raw kind that cooks. It will cook me too, its bits of

lightning zapping through the dust like white knives. Or are those

sparks because I have come to where the meteor landed a hundred

feet off, that break it makes in my father’s land that’s a giant pock

all alive, all glittery with electricity, its dirt dancing up and down

on the radio waves and having a day?

The land here, if it is land I’m on and not road, is as flat as the

road. I am leaning into the wheel and my arms ache trying to lean

it straight. The roads around here are flat and straight. If I’m off the

road, then that meteor hole is around here somewhere for sure and

I will fall into it. I glimpse my father’s crew cut pasture through the

dust—that is, the crew cut that should sh-sh my car’s underside if

I’m driving on the pasture, the crew cut that disappears in another

woof of dust into where I think might be the meteor hole—but then

all that dust shimmies up again and takes over. No sh-sh.

At least the semi still calls behind me. As long as I can hear it, I

know I’m on the road and not where my brother stands, so to speak,

in my father’s field. All of what’s swirling is my brother’s dirt now—I’m

sure it is—his disturbance, his unquiet, his dug dirt whipping up

the storm’s storm. The semi calls again, and this time real lightning

answers it, about the fanciest electricity yet, a tree of it not three feet

from my hood, hot and white at the end of the pasture.

Where I once again see him.

He’s in the same position as before. But I don’t really expect him

to be posed any different—he’s dead, after all. It’s me who should

be moving. Or do I just circle him with all my straight driving? His

mouth is open. What’s he trying to say? The dust the dust the dust—he’s

there forever, trying to be heard. Then he’s gone.

I turn on the ac, because of sweat, the kind that comes when all

the windows are up, and so is fear. What am I afraid of? That he

will take his revenge for every time I turned away from him? That

what he was saying is that I will get what I deserve?

I need my phone, its blank face to sweat into, some nonsense talk

to take place outside of this dust-and lightning-blinded shortcut,

the solace of company or fear shared, and not just this silly moaning

semi that’s obviously more lost than me, that has obviously

driven way off the road and is hoping to make its way back via some

answering moan before it hits the meteor hole—that is, if the driver

knows about the hole and doesn’t think that land is only flat and

straight with no lessons to be learned.

There are lessons to be learned is what seeing him twice in the

dust says to me.

I’ve left the phone at home.

Sweat runs into the lifelines of my palms where the dirt collects,

where I grip the wheel’s plastic. His lifelines are dust, I think, that

kind of dirt. I flex my gritty palms. Forget about lifelines—I

just

want to push down on the pedal and arrive. My workplace isn’t

that far, just a few miles, at least when I started shortcutting down

this road. If I accelerate now, I’ll be there, I’ll be out of this brother-ridden

storm. But before I put on the gas, I honk as if my brother

will hear me and clear away. I honk back at the semi, but there’s no

more moaning.

That’s not good.

A battered blue Chevy passes me—where did that come from?—with

some poor dirt farmer hunched over the wheel, not my brother.

I stare into the dull screen of my side mirror and back at the road,

I stare and I stare. Then the semi finally passes me, one wheel at a

time, with a thank god honk that shakes my car, the dirt swirling

over and around us.

I never think my brother might want to see me.

Out of a storm so thick with dust, a storm so charged with first-rate

prelightning ions that the grit flashes and the car dials fade, a storm

so dark no taillight shines through, though drivers have flicked on

every emergency switch, out of a storm even this dust bowl state

stops for, I spot my brother with a shovel.

Men who shovel look alike. They all face where the wood joins

the metal or at least their glance grazes there on its way to the shovel

tip, so all you see is head or hat—in this case, a cap brim, most

likely lettered Feed and Seed if I know my brother, tilted at some

unreadable angle. What I can read while I creep the car forward,

seeing and not seeing, is that he is not about to dig, he has dug; his

shovel is now raised up. What he has dug swirls around us—me,

in my car creeping through all this flying grit, and him, seen just

in the time it takes to see, where lightning now laves and leaves.

Don’t stop, moans the semi behind me, hauling cattle or, empty,

having hauled. Don’t pull over, says the dust smacking the car.

How do I know it’s him I’ve seen? Only my brother would dig

beside the road in this dust, because he is a digger. Besides, the

road’s right next to my father’s land, and along its perimeter my

brother would dig in postholes for the fences that fall over in the

shrinkage of winter or sag with the swell of summer. Or else he

could be digging to cover up something. Or maybe he was digging

just for the hell of it.

I guess that last is what he is doing, with emphasis on hell. Just the

way our cousin in another state was caught outside her parked

vehicle, holding up her unwrapped baby to a tornado—was

caught more than once—my brother has always dug too deep.

The glimpse goes, is gone. But even if I pull over and park here to

check it out—which I should anyway, given that I can’t see a damn

thing and can hear only this semi shortcutting its own way behind

me, honking now and then like a boat lost in fog, the sound a semi

that could wallop right into me would make if it were too close—even

if I do stop and park and get out and walk over to the field

where he must be, he will not be there. He’s dead.

I tap on my brakes. I make the tapping lively, not nervous, as I go

along so slowly—it’s really an sos, not a signal to my brother behind

me. I push my window button again just to hear my windows roll

their clinch even tighter. I don’t want to breathe his dirt in, all that

grit that could be his. We’re already close, too close, eleven months,

one foot in the womb, the other in the—

I tap it out.

If I could Morse code him with these taps, it would be: I’m not

stopping now, the way I never stopped for you before. But there can

be no ifs to think about with the foghorn of the semi rattling my car.

Or is that sound something else? Some other moan? Some way I

bypass him that is deeper, that I can’t get around at all or hear right?

The dust everywhere is so charged that the radio’s gone static. This

charge is my brother’s fault too, a charge he gives off even when he’s

behind me and dead, being someone with too much electricity in his

head that will forever discharge. He had spells. All that electricity

from his petit and grand mal is probably still around here—so

much of it, it probably killed him. If that isn’t enough, he even attracted

electricity, the raw kind that cooks. It will cook me too, its bits of

lightning zapping through the dust like white knives. Or are those

sparks because I have come to where the meteor landed a hundred

feet off, that break it makes in my father’s land that’s a giant pock

all alive, all glittery with electricity, its dirt dancing up and down

on the radio waves and having a day?

The land here, if it is land I’m on and not road, is as flat as the

road. I am leaning into the wheel and my arms ache trying to lean

it straight. The roads around here are flat and straight. If I’m off the

road, then that meteor hole is around here somewhere for sure and

I will fall into it. I glimpse my father’s crew cut pasture through the

dust—that is, the crew cut that should sh-sh my car’s underside if

I’m driving on the pasture, the crew cut that disappears in another

woof of dust into where I think might be the meteor hole—but then

all that dust shimmies up again and takes over. No sh-sh.

At least the semi still calls behind me. As long as I can hear it, I

know I’m on the road and not where my brother stands, so to speak,

in my father’s field. All of what’s swirling is my brother’s dirt now—I’m

sure it is—his disturbance, his unquiet, his dug dirt whipping up

the storm’s storm. The semi calls again, and this time real lightning

answers it, about the fanciest electricity yet, a tree of it not three feet

from my hood, hot and white at the end of the pasture.

Where I once again see him.

He’s in the same position as before. But I don’t really expect him

to be posed any different—he’s dead, after all. It’s me who should

be moving. Or do I just circle him with all my straight driving? His

mouth is open. What’s he trying to say? The dust the dust the dust—he’s

there forever, trying to be heard. Then he’s gone.

I turn on the ac, because of sweat, the kind that comes when all

the windows are up, and so is fear. What am I afraid of? That he

will take his revenge for every time I turned away from him? That

what he was saying is that I will get what I deserve?

I need my phone, its blank face to sweat into, some nonsense talk

to take place outside of this dust-and lightning-blinded shortcut,

the solace of company or fear shared, and not just this silly moaning

semi that’s obviously more lost than me, that has obviously

driven way off the road and is hoping to make its way back via some

answering moan before it hits the meteor hole—that is, if the driver

knows about the hole and doesn’t think that land is only flat and

straight with no lessons to be learned.

There are lessons to be learned is what seeing him twice in the

dust says to me.

I’ve left the phone at home.

Sweat runs into the lifelines of my palms where the dirt collects,

where I grip the wheel’s plastic. His lifelines are dust, I think, that

kind of dirt. I flex my gritty palms. Forget about lifelines—I

just

want to push down on the pedal and arrive. My workplace isn’t

that far, just a few miles, at least when I started shortcutting down

this road. If I accelerate now, I’ll be there, I’ll be out of this brother-ridden

storm. But before I put on the gas, I honk as if my brother

will hear me and clear away. I honk back at the semi, but there’s no

more moaning.

That’s not good.

A battered blue Chevy passes me—where did that come from?—with

some poor dirt farmer hunched over the wheel, not my brother.

I stare into the dull screen of my side mirror and back at the road,

I stare and I stare. Then the semi finally passes me, one wheel at a

time, with a thank god honk that shakes my car, the dirt swirling

over and around us.

I never think my brother might want to see me.

Recenzii

"A lyrical Midwestern gothic."—Publishers Weekly

"If the novel's focus on the warping effects of grief, with only glancing speculation about what precisely is being grieved, makes it typical of contemporary fiction, Ms. Svoboda distinguishes herself with the peculiarity of her prose, which takes a darting, indirect approach that almost attains the abstraction of a tone poem."—Wall Street Journal

"At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda's Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all."—Brennie Shoup, Superstition Review

"Svoboda's writing is beautiful, rich, and poetic. This surprising novel is an intriguing and thought-provoking read."—Milana Marsenich, Roundup Magazine

"The mystery at the heart of Dog on Fire is compelling, but the real pleasure of the reading experience is Svoboda's punctuated lyricism, sentences and paragraphs that engulf the reader like the dust storm with which the novel begins."—Clifford Garstang, Southern Review of Books

"Svoboda's most recent novel finds the pulse between the every day and the absurd. A richly imaged novel from a writer at the top of her form."—Wendy J. Fox, Electric Lit

“With its fierce wit and insight, Dog on Fire is thrillingly alive to this bewildering moment. This novel about family, grief, and all the ways we remain mysteries to one another is both memorable and brilliant. I’m grateful for Terese Svoboda’s searing vision and for her singular, inventive prose, which always makes me see the world in an entirely new way.”—René Steinke, author of Friendswood

“Tense, poignant, urgent, and at times scathing, with Dog on Fire Svoboda has performed the astonishing dual feat of writing what could be called a contemporary Dust Bowl Gothic novel and creating a pitch-perfect work depicting the feelings of rage, grief, and isolation that come with losing a loved one. Without a doubt, Dog on Fire is Svoboda at her finest.”—Rone Shavers, author of Silverfish

“Dog on Fire is a blisteringly perceptive novel about grief, secrets, and the intractability of love. The mysteries surrounding one man’s death, narrated alternately by his sister and his lover, yield no easy answers in this haunting and darkly witty reckoning.”—Dawn Raffel, author of Boundless as the Sky

“Terese Svoboda has written a continually wonderful novel about grief, family, and the mysterious particularity of each human creature, and the natural secrets we insist on carrying. A terrific book.”—Joan Silber, author of Secrets of Happiness and Improvement

Descriere

Think George Saunders channeling Willa Cather. A ghost story wannabe, Dog on Fire begins with a vision of a brother with a shovel, and ends in Jell-O.