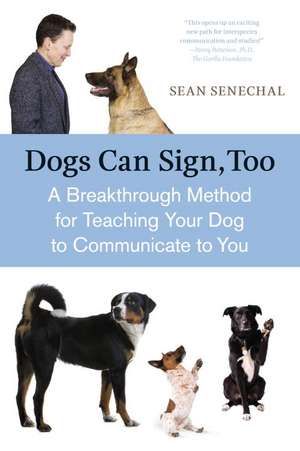

Dogs Can Sign, Too: A Breakthrough Method for Teaching Your Dog to Communicate

Autor Sean Senechalen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

If you’ve ever wondered what dogs would tell us if they could, now you can find out. The K9Sign system teaches dogs to communicate to us–making it a first in any dog training book category.

Dogs Can Sign, Too is the first book dedicated exclusively to the K9Sign system for teaching dogs to communicate to their human companions using a vocabulary of gestures.

This extraordinary education tool, developed by the creator of AnimalSign Language exclusively for the canine community, teaches people and their pets a unique mode of communication that employs an extensive lexicon of specific signs. Sample signs range from general concepts, such as “Food” or “Play” to identifying special treats, such as “Liver” or “Cheese” and specifying a favorite toy, such as “Ball” or “Frisbee.” Signs also include useful questions such as “Who’s that?” or “What type?” to naming a particular friend or family member, or even indicating a stranger.

Learning and practicing K9Sign is a fun, challenging, and rewarding experience for both you and your dog that is sure to deepen the human-canine bond while expanding our ideas about interspecies communication.

Preț: 107.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.54€ • 21.37$ • 16.96£

20.54€ • 21.37$ • 16.96£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781587613531

ISBN-10: 1587613530

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: 35 black-and-white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 153 x 227 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: CELESTIAL ARTS

ISBN-10: 1587613530

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: 35 black-and-white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 153 x 227 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: CELESTIAL ARTS

Notă biografică

SEAN SENECHAL is the founding director of the AnimalSign Center (www.animalsign.org) in Monterey County, California, and the creator of K9Sign Language. She also teaches Human Biology and Behavior at California State University Monterey Bay, as well as Canine Biology and Behavior as part of the CSUMB Extension Program. Sean is a member of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers, the American Behavior Society, and the American Associations for the Advancement of Science. Her work has been featured on Animal Planet, and she is a contributing expert to www.raisingcanine.com, www.simpledogtrainingsecrets.com, and www.thepoochplace.com.

Extras

Chapter 1: AnimalSign Language

K9Sign Language is more than an idea. It is a communication tool that is researched, taught, and practiced at the AnimalSign Center, located in Monterey County, California. Dogs and their people come to the center to learn how to communicate with each other through signs. Learning to sign provides dogs and humans with the opportunity to communicate clearly, for function and fun, at home or at work. Through K9Sign Language, the relationship between dogs and their guardians, caretakers, pet sitters, and trainers is profoundly enhanced. Think about how communication strengthens your human relationships. Why not do the same with your dog? The potential is there, you just have to help your dog communicate better by recognizing her natural signs, and by showing her how to sign to you.

Outside the Center, dogs are already learning how to communicate with us through simple movements such as sitting, barking, nudging, alerting, and looking. Many make requests with simple moves such as door tapping to indicate a desire to go out. Some learning on the part of animals has been taught, while other efforts to communicate seem instinctual. Dogs who are trained to assist hearing-impaired humans often come to recognize and respond to many oral or signed words on their own. Many scientists, trainers, teachers, and enthusiasts have contributed to the education of animals for service, sport, and pleasure. With our help, dogs learn obedience, agility, tracking, search and rescue, assistance, and other remarkable skills. And dogs are not the only animals who learn from humans. Horses learn tricks, dressage, roping, and service skills. Animals learn, learn, learn. We even try to prevent animals from learning certain skills because we don’t want them to become bad habits (from our point of view). All these actions are mere fragments of what animals might be capable of doing; we have tapped only the surface of their cognitive abilities and skills. By providing them with a language tool, such as K9Sign Language, we might not only learn about their cognition, but just imagine what they might learn.

Expressing Details

Dogs are aware of many details about the world that humans are not. They smell, see, and hear things we don’t. With natural body language, they can grossly express their perceptions. Yet they have no specific way to express their detailed perceptions, thoughts, and desires to us. It is up to us to know dogs well enough to make educated guesses.

Dogs can be trained to identify cancer cell odors for both late and early stage lung and breast cancer, but the dogs communicate only by sitting next to the vial holding the cells they were asked to identify. Imagine if these dogs learned four K9Signs: Early Lung Cancer, Late Lung Cancer, Early Breast Cancer, Late Breast Cancer. With this the dogs could identify on a human or animal subject which stage and disease was present on one person, rather than being asked to answer with a sit when they smell any cancer. Dogs could be specific. Without the tools to be specific and elaborate, animals can’t communicate the details. With the tools, the animals could communicate details we can’t perceive ourselves.

Often animals move and vocalize in an effort to communicate something they know. We may understand the general idea, but not the details of what they are saying. Their natural body language only suggests their trains of thought and feelings. How frustrating to have such limited vocabulary (sit, stand, down, bark, growl, paw, dig, look) when they seem to have so much more to say. We can observe and reason, but only guess what dogs are communicating. Some professionals, such as dog language experts Roger Abrantes and Stanley Coren, surely read these animals better than others. But even their translations may be indirect or inaccurate. Animals might be capable of much more elaborate communication. With additional language skills, dogs could directly tell us what they are “saying,” and we could understand and respond.

Some people state they can sense, using some invisible, unmeasurable stimuli, then intuit, translate, and understand what animals are thinking. Some people, with their perceptions and interpretations of animal behavior, using a variety of techniques, have much to contribute to our understanding animal cognition. This book does not delve into those other techniques, but I do value sharing and pooling our diverse methods, resources, and knowledge to better understand and communicate with our animals.

If animals have the cognitive ability to know what they are trying to say, why can’t they directly, visibly tell us in detail? Because they have no organized, agreed-upon language other than a few natural body gestures learned during socialization. They lack a tool, a code, to precisely map their thoughts into visible signs. We haven’t taught them a method of communicating details in a visible or oral form that we can interpret. As much as we observe and spend time with them, as many treats we offer and tricks we engage them in, we have not yet taught dogs an expanded productive language (language that is produced). We leave their communication skills natural, but undeveloped; we leave them illiterate. Would we leave our human children in such a limited state?

What kind of productive language might be useful teach animals? One that is made for and customized for animal bodies and minds; one that includes signs for humans to communicate to animals, but specifically focuses on signs for the animals to communicate to humans. Animals, such as dogs and horses can’t vocalize as extensively as we do and they can’t fingerspell (not yet, anyway). Ah! But they can move their many body parts in various combinations and patterns, in space and in time! They have a natural body language to seed this learning. This mobility and the ability to learn are the foundations of AnimalSign Language–and specifically K9Sign Language for dogs.

Having a language ready to teach is one thing; learning it is another. Dogs have inborn mechanisms that enable them to learn, problem solve, and perform simple communications. Can dogs learn a simple language, or our type of true language? Can they learn a language that can be divided into receptive and productive components? Receptive language focuses on the understanding of the meaning of signed, written, or spoken words. Productive refers to producing words, for example by gesturing or vocalizing. There is documented and anecdotal evidence for dogs receptively learning language. Animals seem to understand what we say, sign, and possibly write. They run to the door when they hear the word “walk,” and grab their favorite ball when they see people gesture Play, and on seeing a street sign with the written word STOP, a dog for the blind will stop.

Researched evidence in this area is growing. Dogs have learned some receptive oral, signed, and written language. They understand our many languages, our spoken words, visible signs, and a few of our written words. Recently a particularly talented dog named Rico who understands two hundred spoken words was tested by animal psychologist Juliane Kaminski and others, and commented on by Paul Bloom in Science (June 2004). Dr. Bonita Bergin, founder of Canine Companions for Independence, has attempted to teach dogs to read (and posted YouTube videos) at the Assistance Dog Institute in California.

Capacity for Language?

Do dogs have the capacity to learn a productive language or true language? A few dog experts acknowledge we just don’t know; we haven’t tried or tested this ability scientifically. Virtually all others say or assume the answer is no. They don’t consider the possibility. Why? I suggest this attitude is prevalent because dogs aren’t already talking, writing, and producing language (other than natural body language). The assumed inability to learn a nonnatural language comes also from the idea that these animals don’t have the appropriate body type for expressing this type of language. When considering productive language, the focus is usually on the voice, though the whole body is available. Some scientists might claim dogs don’t have the cognition, the innate skills, or the instinct to produce language. Otherwise, they’d already be creating and learning a language on their own. But don’t animals living together in stable groups for long periods of time build common vocabulary onto their existing body language? For animals such as chimpanzees, this type of expanded communication has been clearly documented by Dr. Jane Goodall and others. Perhaps other animals are able to do the same thing. We should continue to watch the animals in our lives, carefully, for added vocabulary.

Along with possible cognition issues, dogs have a huge physical challenge (from a human perspective). They are, necessarily, on their movable limbs all day, and their voices appear to have limited use for expanded language (in the range we can hear). (Perhaps, with a human professional voice trainer, they could learn to produce many more specific sounds.) In contrast, we humans are only on two of our limbs and use the other two for manipulations and language. We have our hands and voice available for communication anytime.

A glaring omission in animal literature is the perception of dogs as potential productive language learners. The idea that we can teach them productive language is absent. Experts are busy productively focusing on developing a dog’s known talents and skills. Many see what dogs have done and can now do, rather than what they could do. In much of this literature, I can’t help but read these phrases between the lines: “Dogs can’t learn language because their brains are too small.” “Wrong body type.” “They can’t produce language because they don’t have a vocal apparatus, or hands, like ours.” “They can’t because they haven’t.” “They can’t because they don’t.”

While it is true that dogs have different brains than humans, animals and humans also have many similar, core anatomical structures (hypothalamus, temporal and frontal lobes, limbic and sensory systems) involved in learning, anticipation, emotions, and feelings. We haven’t yet sufficiently explored the cognitive function of animal language neuroanatomy. (It would be fascinating to compare the neuroanatomy of canine identical siblings as one is taught language and the other is not.) Canine brains aren’t as convoluted, nor is their cortex as large as ours. But those are not the only determinant wirings of language capability. Dogs are very skilled at anticipation and detection of subtle cues. These animals also have more sensitive, neuroanatomical structures, when it comes to smell, movement detection, and some aspects of hearing and vision. (How, I wonder, do their brains cognitively network a map of their expansive sense of smell?)

With these and other similarities, some level of anthropomorphism (in reference to learning and feeling systems) is appropriate. While the sophistication and networking capabilities of these systems do differ from ours, and thus, we might expect some differences in extent of ability. It would be fascinating to uncover the extent of similarities and differences while attempting to teach language. In the end–and most importantly–although many animals have picked up receptive language on their own, we have not taught them productive language. So, whatever we think of their anatomical differences, we really don’t know what they could do–if taught. That potential for language learning is what we are exploring at the AnimalSign Center.

The expectation that dogs can learn productive language isn’t there for most people. Many have just accepted and become used to perceiving dogs as nonlanguage learners. Or perhaps some see dogs only as receptive learners, but not as articulate, language producers. As a teacher, I take a different approach. I will presume dogs can learn language, until they provide evidence they can’t. If a human child isn’t learning at school, we should not immediately come to the conclusion that the student can’t learn. The student could be in the wrong class, with the wrong teacher, using the wrong book, being taught with the wrong method. My hypothesis with animals is that they aren’t learning productive language, or true language, because we haven’t taught them. If we try to teach language to animals and they don’t learn, we would still need to consider that this failing could be ours. We may not be teaching with the appropriate methods or under the right conditions. Perhaps they may not be learning because we are using the wrong language structure for them. Many other reasons could exist. Only as a last answer should we consider that animals simply can’t learn true language, as we define and teach it. I presume that students (regardless of the body, the [dis]abilities, and the conditions) can learn. I take it upon myself to find ways to make learning happen. I take this same approach to animals–dogs in particular.

Let’s give our canine companions the opportunity to try to learn, and see what they do with true language education. There is everything to gain and nothing to lose (except the belief that true language is the private domain of primates and birds). If dogs learn language, it may not be as sophisticated as ours, but it might be sufficiently different to warrant a new line of questioning, investigating, and thinking when it comes to language and animals. We just don’t know, yet.

While attempting to teach signing to animals, I have seen horses and dogs learn new gestures linked and associated in some way to a specific object, such as a ball or brush. A dog might spontaneously sign Ball, meaning she wants to play with it, a horse might sign Brush, meaning she wants to be brushed. (Later in this book you will learn how to test that your animal understands meaning.) These behaviors need not be commanded, nor cued. These gestures appear to represent something meaningful to them (food, toy, play, water, open door). I have seen animals communicate with these newly learned gestures. Chal, my German shepherd, has gestured with her food paw (not her toy paw) when I showed her new foods that she had never seen. She has also used the sign Toy for my cat before she learned to sign Cat. Chal has spontaneously made up her own sign and her own move to convey a message to me. She lifted her right paw and bent it toward me to convey (what I interpreted) as Teach Me the Sign. These gestures are a step, but they do not mean that Chal or other animals that use gestures have learned a structured language. But this step is encouraging enough for me to continue teaching and testing human and animal–human-animal–teams. With many teams working, we can accumulate and share more data to get an indication of whether animals can learn or are learning signs, a language, or a formal language. If dogs are not using gestures as signs, for true language, then what are they doing? I aim to understand their use of K9Sign wherever it takes me, physically and intellectually.

K9Sign Language is more than an idea. It is a communication tool that is researched, taught, and practiced at the AnimalSign Center, located in Monterey County, California. Dogs and their people come to the center to learn how to communicate with each other through signs. Learning to sign provides dogs and humans with the opportunity to communicate clearly, for function and fun, at home or at work. Through K9Sign Language, the relationship between dogs and their guardians, caretakers, pet sitters, and trainers is profoundly enhanced. Think about how communication strengthens your human relationships. Why not do the same with your dog? The potential is there, you just have to help your dog communicate better by recognizing her natural signs, and by showing her how to sign to you.

Outside the Center, dogs are already learning how to communicate with us through simple movements such as sitting, barking, nudging, alerting, and looking. Many make requests with simple moves such as door tapping to indicate a desire to go out. Some learning on the part of animals has been taught, while other efforts to communicate seem instinctual. Dogs who are trained to assist hearing-impaired humans often come to recognize and respond to many oral or signed words on their own. Many scientists, trainers, teachers, and enthusiasts have contributed to the education of animals for service, sport, and pleasure. With our help, dogs learn obedience, agility, tracking, search and rescue, assistance, and other remarkable skills. And dogs are not the only animals who learn from humans. Horses learn tricks, dressage, roping, and service skills. Animals learn, learn, learn. We even try to prevent animals from learning certain skills because we don’t want them to become bad habits (from our point of view). All these actions are mere fragments of what animals might be capable of doing; we have tapped only the surface of their cognitive abilities and skills. By providing them with a language tool, such as K9Sign Language, we might not only learn about their cognition, but just imagine what they might learn.

Expressing Details

Dogs are aware of many details about the world that humans are not. They smell, see, and hear things we don’t. With natural body language, they can grossly express their perceptions. Yet they have no specific way to express their detailed perceptions, thoughts, and desires to us. It is up to us to know dogs well enough to make educated guesses.

Dogs can be trained to identify cancer cell odors for both late and early stage lung and breast cancer, but the dogs communicate only by sitting next to the vial holding the cells they were asked to identify. Imagine if these dogs learned four K9Signs: Early Lung Cancer, Late Lung Cancer, Early Breast Cancer, Late Breast Cancer. With this the dogs could identify on a human or animal subject which stage and disease was present on one person, rather than being asked to answer with a sit when they smell any cancer. Dogs could be specific. Without the tools to be specific and elaborate, animals can’t communicate the details. With the tools, the animals could communicate details we can’t perceive ourselves.

Often animals move and vocalize in an effort to communicate something they know. We may understand the general idea, but not the details of what they are saying. Their natural body language only suggests their trains of thought and feelings. How frustrating to have such limited vocabulary (sit, stand, down, bark, growl, paw, dig, look) when they seem to have so much more to say. We can observe and reason, but only guess what dogs are communicating. Some professionals, such as dog language experts Roger Abrantes and Stanley Coren, surely read these animals better than others. But even their translations may be indirect or inaccurate. Animals might be capable of much more elaborate communication. With additional language skills, dogs could directly tell us what they are “saying,” and we could understand and respond.

Some people state they can sense, using some invisible, unmeasurable stimuli, then intuit, translate, and understand what animals are thinking. Some people, with their perceptions and interpretations of animal behavior, using a variety of techniques, have much to contribute to our understanding animal cognition. This book does not delve into those other techniques, but I do value sharing and pooling our diverse methods, resources, and knowledge to better understand and communicate with our animals.

If animals have the cognitive ability to know what they are trying to say, why can’t they directly, visibly tell us in detail? Because they have no organized, agreed-upon language other than a few natural body gestures learned during socialization. They lack a tool, a code, to precisely map their thoughts into visible signs. We haven’t taught them a method of communicating details in a visible or oral form that we can interpret. As much as we observe and spend time with them, as many treats we offer and tricks we engage them in, we have not yet taught dogs an expanded productive language (language that is produced). We leave their communication skills natural, but undeveloped; we leave them illiterate. Would we leave our human children in such a limited state?

What kind of productive language might be useful teach animals? One that is made for and customized for animal bodies and minds; one that includes signs for humans to communicate to animals, but specifically focuses on signs for the animals to communicate to humans. Animals, such as dogs and horses can’t vocalize as extensively as we do and they can’t fingerspell (not yet, anyway). Ah! But they can move their many body parts in various combinations and patterns, in space and in time! They have a natural body language to seed this learning. This mobility and the ability to learn are the foundations of AnimalSign Language–and specifically K9Sign Language for dogs.

Having a language ready to teach is one thing; learning it is another. Dogs have inborn mechanisms that enable them to learn, problem solve, and perform simple communications. Can dogs learn a simple language, or our type of true language? Can they learn a language that can be divided into receptive and productive components? Receptive language focuses on the understanding of the meaning of signed, written, or spoken words. Productive refers to producing words, for example by gesturing or vocalizing. There is documented and anecdotal evidence for dogs receptively learning language. Animals seem to understand what we say, sign, and possibly write. They run to the door when they hear the word “walk,” and grab their favorite ball when they see people gesture Play, and on seeing a street sign with the written word STOP, a dog for the blind will stop.

Researched evidence in this area is growing. Dogs have learned some receptive oral, signed, and written language. They understand our many languages, our spoken words, visible signs, and a few of our written words. Recently a particularly talented dog named Rico who understands two hundred spoken words was tested by animal psychologist Juliane Kaminski and others, and commented on by Paul Bloom in Science (June 2004). Dr. Bonita Bergin, founder of Canine Companions for Independence, has attempted to teach dogs to read (and posted YouTube videos) at the Assistance Dog Institute in California.

Capacity for Language?

Do dogs have the capacity to learn a productive language or true language? A few dog experts acknowledge we just don’t know; we haven’t tried or tested this ability scientifically. Virtually all others say or assume the answer is no. They don’t consider the possibility. Why? I suggest this attitude is prevalent because dogs aren’t already talking, writing, and producing language (other than natural body language). The assumed inability to learn a nonnatural language comes also from the idea that these animals don’t have the appropriate body type for expressing this type of language. When considering productive language, the focus is usually on the voice, though the whole body is available. Some scientists might claim dogs don’t have the cognition, the innate skills, or the instinct to produce language. Otherwise, they’d already be creating and learning a language on their own. But don’t animals living together in stable groups for long periods of time build common vocabulary onto their existing body language? For animals such as chimpanzees, this type of expanded communication has been clearly documented by Dr. Jane Goodall and others. Perhaps other animals are able to do the same thing. We should continue to watch the animals in our lives, carefully, for added vocabulary.

Along with possible cognition issues, dogs have a huge physical challenge (from a human perspective). They are, necessarily, on their movable limbs all day, and their voices appear to have limited use for expanded language (in the range we can hear). (Perhaps, with a human professional voice trainer, they could learn to produce many more specific sounds.) In contrast, we humans are only on two of our limbs and use the other two for manipulations and language. We have our hands and voice available for communication anytime.

A glaring omission in animal literature is the perception of dogs as potential productive language learners. The idea that we can teach them productive language is absent. Experts are busy productively focusing on developing a dog’s known talents and skills. Many see what dogs have done and can now do, rather than what they could do. In much of this literature, I can’t help but read these phrases between the lines: “Dogs can’t learn language because their brains are too small.” “Wrong body type.” “They can’t produce language because they don’t have a vocal apparatus, or hands, like ours.” “They can’t because they haven’t.” “They can’t because they don’t.”

While it is true that dogs have different brains than humans, animals and humans also have many similar, core anatomical structures (hypothalamus, temporal and frontal lobes, limbic and sensory systems) involved in learning, anticipation, emotions, and feelings. We haven’t yet sufficiently explored the cognitive function of animal language neuroanatomy. (It would be fascinating to compare the neuroanatomy of canine identical siblings as one is taught language and the other is not.) Canine brains aren’t as convoluted, nor is their cortex as large as ours. But those are not the only determinant wirings of language capability. Dogs are very skilled at anticipation and detection of subtle cues. These animals also have more sensitive, neuroanatomical structures, when it comes to smell, movement detection, and some aspects of hearing and vision. (How, I wonder, do their brains cognitively network a map of their expansive sense of smell?)

With these and other similarities, some level of anthropomorphism (in reference to learning and feeling systems) is appropriate. While the sophistication and networking capabilities of these systems do differ from ours, and thus, we might expect some differences in extent of ability. It would be fascinating to uncover the extent of similarities and differences while attempting to teach language. In the end–and most importantly–although many animals have picked up receptive language on their own, we have not taught them productive language. So, whatever we think of their anatomical differences, we really don’t know what they could do–if taught. That potential for language learning is what we are exploring at the AnimalSign Center.

The expectation that dogs can learn productive language isn’t there for most people. Many have just accepted and become used to perceiving dogs as nonlanguage learners. Or perhaps some see dogs only as receptive learners, but not as articulate, language producers. As a teacher, I take a different approach. I will presume dogs can learn language, until they provide evidence they can’t. If a human child isn’t learning at school, we should not immediately come to the conclusion that the student can’t learn. The student could be in the wrong class, with the wrong teacher, using the wrong book, being taught with the wrong method. My hypothesis with animals is that they aren’t learning productive language, or true language, because we haven’t taught them. If we try to teach language to animals and they don’t learn, we would still need to consider that this failing could be ours. We may not be teaching with the appropriate methods or under the right conditions. Perhaps they may not be learning because we are using the wrong language structure for them. Many other reasons could exist. Only as a last answer should we consider that animals simply can’t learn true language, as we define and teach it. I presume that students (regardless of the body, the [dis]abilities, and the conditions) can learn. I take it upon myself to find ways to make learning happen. I take this same approach to animals–dogs in particular.

Let’s give our canine companions the opportunity to try to learn, and see what they do with true language education. There is everything to gain and nothing to lose (except the belief that true language is the private domain of primates and birds). If dogs learn language, it may not be as sophisticated as ours, but it might be sufficiently different to warrant a new line of questioning, investigating, and thinking when it comes to language and animals. We just don’t know, yet.

While attempting to teach signing to animals, I have seen horses and dogs learn new gestures linked and associated in some way to a specific object, such as a ball or brush. A dog might spontaneously sign Ball, meaning she wants to play with it, a horse might sign Brush, meaning she wants to be brushed. (Later in this book you will learn how to test that your animal understands meaning.) These behaviors need not be commanded, nor cued. These gestures appear to represent something meaningful to them (food, toy, play, water, open door). I have seen animals communicate with these newly learned gestures. Chal, my German shepherd, has gestured with her food paw (not her toy paw) when I showed her new foods that she had never seen. She has also used the sign Toy for my cat before she learned to sign Cat. Chal has spontaneously made up her own sign and her own move to convey a message to me. She lifted her right paw and bent it toward me to convey (what I interpreted) as Teach Me the Sign. These gestures are a step, but they do not mean that Chal or other animals that use gestures have learned a structured language. But this step is encouraging enough for me to continue teaching and testing human and animal–human-animal–teams. With many teams working, we can accumulate and share more data to get an indication of whether animals can learn or are learning signs, a language, or a formal language. If dogs are not using gestures as signs, for true language, then what are they doing? I aim to understand their use of K9Sign wherever it takes me, physically and intellectually.

Recenzii

“This opens up an exciting new path for interspecies communication and studies!"–Penny Patterson, Ph.D., The Gorilla Foundation

Cuprins

Contents

Introduction - 1

Chapter 1

AnimalSign Language - 9

Chapter 2

K9Sign Language - 23

Chapter 3

Understanding How Dogs Learn - 38

Chapter 4

Learning K9Sign - 53

Chapter 5

Before You Teach K9Sign - 63

Chapter 6

Before Your Dog Learns K9Sign - 75

Chapter 7

How to Teach the Human K9Signs to Your Dog - 78

Chapter 8

Dogs Can Sign to You - 111

Chapter 9

How to Teach the Canine K9Signs to Your Dog - 117

Chapter 10

The Future of Signing Animals - 194

Acknowledgments - 199

The AnimalSigners - 202

References and Suggested Reading - 206

Index - 212

Introduction - 1

Chapter 1

AnimalSign Language - 9

Chapter 2

K9Sign Language - 23

Chapter 3

Understanding How Dogs Learn - 38

Chapter 4

Learning K9Sign - 53

Chapter 5

Before You Teach K9Sign - 63

Chapter 6

Before Your Dog Learns K9Sign - 75

Chapter 7

How to Teach the Human K9Signs to Your Dog - 78

Chapter 8

Dogs Can Sign to You - 111

Chapter 9

How to Teach the Canine K9Signs to Your Dog - 117

Chapter 10

The Future of Signing Animals - 194

Acknowledgments - 199

The AnimalSigners - 202

References and Suggested Reading - 206

Index - 212